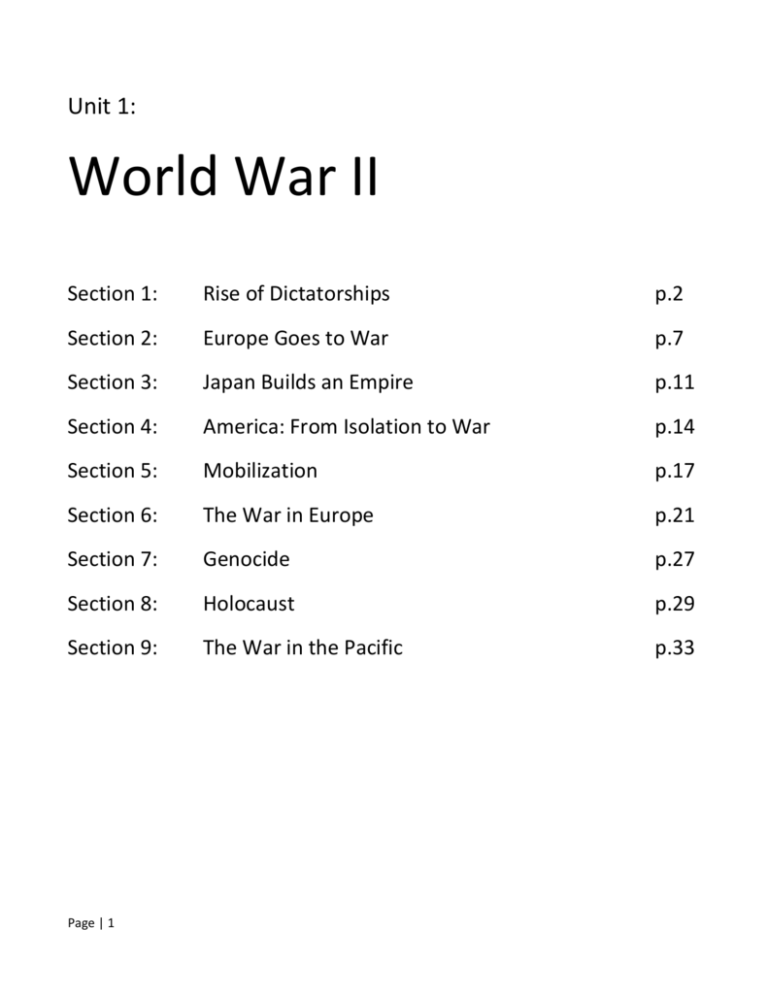

Unit 1: World War II Section 1: Rise of Dictatorships p.2 Section 2

advertisement