2.1. Mary Rowlandson`s Image of the Indians 3

advertisement

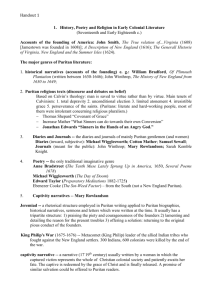

Mary Rowlandson’s Image of the Indians In A True History of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson 1 Table of Contens 1 1. Introduction 2 2.1. Mary Rowlandson’s Image of the Indians 3 2.2. Indian Society – a „Lawless Animality“? 5 2.3. Change of Mary Rowlandson’s Attitude towards the Indians 7 3. Conclusion 9 4. Bibliography 11 1. Introduction When the first Europeans began to settle permanently in the New World at the beginning of the 17th Century, nobody would have imagined how strong their influence on the Indians would be. Quickly European settlements expanded, and the colonists came into close proximity with Indian places. The result proved fatal: Indian 2 lands, then cultivated by the whites, became unsuitable, the number of Indians decreased, there was less food and land, and many natives became demoralized and desperate (Enduring Vision 63-65). A conflict between the two ‘races’ was therefore unavoidable, one example being King Philip’s War (1675-1676), in which the Narragansett tribe fought against the whites. As a result, Lancaster, a white settlement in Massachusetts, was attacked. Many white settlers died, some were captured. Among them was Mary Rowlandson, the wife of the town’s minister, who wrote a narrative about her experience (Davis 50). Her text is not only of literary value, but it is also a rare example of a publication by a Puritan woman, which was rather rare during the early American period. Her account became a bestseller overnight not only in America but also in Great Britain (Derounian 94). In the following study I address myself to Mary Rowlandson’s attitude towards the Indians as displayed throughout her narrative. The problem, however, is that many “captivity writers approached the subject with strong biases, either negative or positive, towards Indians, obtaining a realistic image of Indians from the captivity narrative is extremely difficult.” Also, observations “were recorded through the lens of their prejudices and misunderstandings” (Derouninan 85). The same applies to Mary Rowlandson’s narrative, which at least does not only portray negative examples, (although she never reveals her judgment of the “bloody heathen”); Rowlandson admits that there are positive aspects in Indian society and describes them as far as they were compatible with her Puritan life. 3 The chapters that follow are to convey her initial image of the Indian and in how far it changes during captivity, as well as to compare Indian society with her own. 2.1. Mary Rowlandson’s Image of the Indians Mary Rowlandson is captured with her three children during an attack by an Indian tribe on Lancaster. She watches her house is burnt down and how many of her relatives and friends are wounded or killed. Mrs. Rowlandson is shocked and perplexed by the coldbloodedness of the attackers and calls them “bloody” and “merciless heathen” (Mary Rowlandson 299)1 or “hell-hounds” in contrast to the “company of sheep”, the Christians. Such contrasts reappear throughout the whole narrative: “There was nothing but Indians...and no Christian soul near me” (MR 307), or “I was not so much hemmed in with the merciless and cruel heathen, but now as much with pitiful, tender-hearted and compassionate Christians” (MR 326). During the first night of her captivity she is confronted with unfamiliar ceremonies of the “black creatures” who are roaring, singing and dancing; she describes the place to be a “lively resemblance of hell” (MR 300). In her opinion Indians are not human beings ; she rather describes them with animal-like qualities. As a Puritan “goodwife” she feels herself superior and agrees with the general Puritan view. Not being familiar with the Indian way of life, she is unable to ride a horse without falling down. The “inhumane creatures” (MR 302) laugh at her, which concerns her very much, whereas other incidents do not seem to shock her that much. Michelle Burnham points out that “it is striking that what 1 All page references are to the Norton Anthology of American Literature 5 th ed. 4 seems to most unnerve and upset Mary Rowlandson about the Indians – far more than the bundle of bloodied Puritan garments [...] are their laughter and celebration” (69). Mrs. Rowlandson applies a different standard than the reader expects, but here it can be seen how the narrator is driven by her subjective emotions and impressions. Consequently, one has to be very careful with regard to her judgment of the Indians. A very sad experience is the death of Rowlandson’s six-yearold daughter Sarah, who, after the third remove, dies of a gunshot wound that was inflicted on her during the attack in the Lancaster settlement. Having lost her child, Rowlandson breaks down and falls into a state of overpowering grief. She wants her child to be buried in a dignified way; instead the little girl is left behind in the wilderness (MR 303). Even though her two remaining children live in the same settlement and mourn over their sister’s death, Rowlandson is not allowed to comfort them. Emotionally and physically weakened, she is not even able to harbor bitter resentment for the Indians. Burnham summarizes correctly: “The Indian habitat remains a desolate wilderness in which the Christian woman recognizes no beauty or solace, territory foreign to civilization.” The same can be said about the Indians themselves for whom the narrator does not have any positive feelings; however, slowly but steady, her attitude towards them is changing for the better – at the beginning of her captivity she had no respect towards the Indians. She considered them to be animals rather than to have human features at all. While living with the tribe she starts to change her point of view. 2.2. Indian Society – a “Lawless Animality”? 5 Having lived in Puritan society all her life, Mary Rowlandson does not know anything else. When captured by the Indians, she is confronted with a totally different way of life. First she does not even want to regard the Indian group as a society; she calls them “inhuman creatures”, as they are found to be not properly human (MR 301). Having no real home but wandering around in the wilderness provides the impression that the Indians are uncivilized. The first remove is a shock to her: This was the dolefulest night that ever my eyes saw. Oh the roaring, and singing and dancing, and yelling of those black creatures in the night, which made the place a lively resemblance of hell. And as miserable was the waste that was there made of horses, cattle, sheep, swine, calves, lambs, roasting pigs and fowl (which they had plundered in the town), some roasting, some lying and burning, and some boiling to feed our merciless enemies: who were joyful enough, though we were disconsolate (MR 300). It takes time until Mary Rowlandson “sees the Indians not as simple ‘savages’ but as possessing a social structure with a hierarchy that, at least in her eyes, bears similarities to her own” (Toulouse 657). The Puritans teach that the wife “accepts all males as authorityfigures”. Rowlandson soon realizes that “males hold power in Indian society just as in her own” (Davis 54). Therefore she tries to stay in favor with those who control her life, whereas she is not willing to respect and obey the female members as ling as she is not threatenend. Her master Quannopin, whom she even calls “the best friend I had of an Indian” (MR 312), treats her in a kind way, promising that she will return home soon. So, too, does King Philip who consoles 6 her with the words “two weeks more and you shall be Mistress again” (MR 319), knowing how difficult the situation for a Puritan woman must be. Also, it is a male person who gives her the Bible (MR 304), whereas a female snatches it from her and throws it away. When she refuses to give away a pieces of her apron, she is insulted and threatened until she gives in (MR 314). In a nutshell it can be said that Rowlandson “taking great pains to portray Indian women as cruel and capricious creatures, she names their offences more frequently and their kindnesses less often than those of the males” (Davis 55). Furthermore, the longer Mrs. Rowlandson is among the Indians, the more she joins in their daily lives. As she has skills in sewing and knitting, she begins to assume a distinct role in the Indian community. Her interaction with the natives increases because of her production of clothes and places her in a “defined position within their economy” (Burnham 66). She either receives money or trade goods for her work, which she again reintroduces back to the Indians. Mitchell Breitwieser notes that “Rowlandson’s mourning leads her towards recognizing Indian society as a society, rather than a lawless animality” (148/149). 2.3. Change of Mary Rowlandson’s attitude towards the Indians The impression Mary Rowlandson has of the Indians at the beginning of her captivity and the one she has adopted by its ending differs very much. Whereas she first sees the Indians as inhuman, bloody and merciless pagans, her vies changes the longer she stays 7 with the Indians. “over the nearly three-month period of her captivity, Mary Rowlandson undergoes a gradual process of acculturation,” Michelle Burnham notes (66), as can be observed in all areas of life, food, trade, discourse, language, etc. In the second week of her captivity, Mary gets food and although she is very hungry, it is hard for her to swallow the “filthy trash”. It only takes another week until she changes her mnd and describes the food as “sweet and savory to my taste” (MR 306). Later on, after the eighteenth Remove Mary gets boiled horses feet. She is so hungry, that she takes away the portion of one English child because it could not have eaten the tough meat anyway. Derounian interprets it this way: Indoctrinated by her Puritan background to hate Indians, Rowlandson had difficulty consciously admitting a certain respect for her Indian captors. She therefore displaces her gradual acceptance of Indian culture onto her description of Indian foods (92). I do not agree with Derounian’s statement because it seems to be far-fetched to me. I agree that Mrs. Rowlandson more and more subconsciously identifies herself with her captors but I do not think she expresses her acceptance through the description of meals. In my opinion she just gets used to the Indian food because she has no other possibilities. Her Identification with the captors can be observed differently. Soon the captive participates in the Indian community; she has skills in sewing and knitting and is therefore asked to produce clothes for the families. In return she is given money, food or other goods which she again reintroduces back; “Her entry into exchange lifts her out of the abjection of being on the dole, and thus creates a 8 measure of equality between herself and the captors” (Breitwieser 146). During the seventh remove she already starts to identify with her captors. She notes ”we had a wearisome time of it the next day,” (MR 307) but when seeing English paths and fields she is aware of her situation and speaks about the Indians as “they”. After the seventeenth Remove the reader learns that Mary has become used to communicating with the natives, so that it almost seems normal for her. After an exhausting journey the group comes to an Indian town where they all sit down and start discoursing, “but I was almost spent, and could scarce speak” (MR 318). During the nineteenth Remove, Mary is called to council where she is asked to sit down among them “as I was wont to do, as their manner is [...] they bid me speak” (MR 320). The precondition that she can communicate with the Indians is that she has to learn their language. And in learning a people’s language one becomes automatically involved. A language characterizes a people and makes it feel as one group. Although the Indians captured Mary Rowlandson, they do not only behave towards her in a negative way. She wonders, “Sometimes I met with favor, and sometimes with nothing but frowns” (MR 311). Although this is a flat statement, because does not seem to think about the reasons for this, it brings the Indian’s behavior to the point. Sometimes the captors are very friendly: they offer her food (MR 306), comfort her when she is sad (“I fell aweeping [...] the old squaw told me, to encourage me, that fi I wanted some victuals; I should come to her [...] the first time I had such kindness showed me” MR 319.), give her a Bible (MR 304), let her join the community, etc. On the other hand Rowlandson is a prisoner of war. Thus it is not surprising that she is confronted with 9 violence and that she is treated badly. Her youngest child Sarah is dead which of course causes great affliction to her. She therefore hates the Indians, and this makes an approach extremely difficult. Sometimes she does not get food, she is threatened frequently, and she is often not allowed to see her children. Nevertheless she admits and writes down when something positive happens. This approach shows a women’s insight, which one did probably not come across very often during that period of time due to the patriarch system which did not gave women much freedom. 3. Conclusion As we have seen in the above mentioned aspects, the image of the Indian plays an intrinsic role in Mary Rowlandson’s captivity narrative. It should be pointed out that her account is not a typical captivity text that describes and promotes the fixed negative stereotype of Indians. Instead, also a positive image is conveyed. Of course, it cannot be said that Rowlandson provides an overall positive image of the tribe; at least she does not deny and relate contrary experiences she has had. She never really reveals her picture of the “bloody heathen” because there are points she could have never agreed with as a Puritan woman, such as their exercise of religion or the ceremonies. In fact, she created a great work – which was rather unusual for a woman, who were prevented by many circumstances during the colonial period to express themselves. By this piece of literature she presents a step forward tolerating Native Americans whose homelands and holy grounds were increasingly taken by whites. Her narrative may thus be seen as a first approach between the Indians 10 and the whites. It developed into a cherished and frequently-read classic that is still worth being read even nowadays. 4. Bibliography Boyer, Paul S. et al. The Enduring Vision: A History of the American People. 3rd ed.. Lexington, MA: Heath, 1996. Breitwieser, Mitchell R. American Puritanism and the Defense of Mourning: Religion, Grief and Ethnology in Mary White 11 Rowlandson’s Captivity Narrative. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1990. Burnham, Michelle. “The Journey Between: Liminality and Dialogism in Mary White Rowlandson’s Captivity Narrative.” Early American Literature 28:1 (1993) 60-75. Davis, Margaret H. “Mary White Rowlandson’s Self-Fashioning as Puritan Goodwife.” Early American Literature 27:1 (1992): 49-60. Derounian-Stodala, Kathryn Zabelle & James A. Levernier. The Indian Captivity Narrative, 1550-1900. New York: Twayne, 1993. Logan, Lisa. “Mary Rowlandson’s Captivity and the ‘Place’ of the Woman Subject.” Early American Literature 28:3 (1993): 255277. Rosenmeier, Jesper. “Text and Context in Mary Rowlandson’s Captivity Narrative.” American Quarterly 44:2 (1992): 255261Rowlandson, Mary. “A Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson.” The Norton Anthology of the American Literature. Gen. ed. Nina Baym. 5th ed. Vol.I New York: Norton, 1998. 298-330Toulouse, Teresa A. “’My Own Cretid’: Strategies of (E)Valuation in Mary Rowlandson’s Captivity Narrative.” American Literature 64:4 (1992): 655-676. 12 13