EmiliaCharacterDissection.doc

advertisement

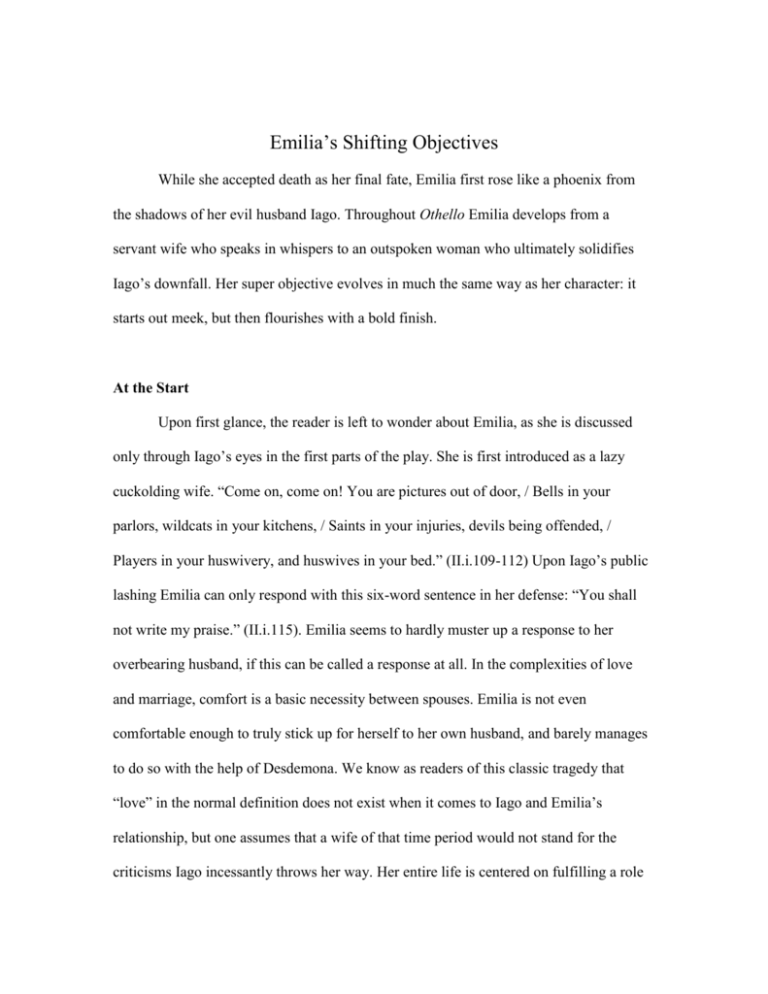

Emilia’s Shifting Objectives While she accepted death as her final fate, Emilia first rose like a phoenix from the shadows of her evil husband Iago. Throughout Othello Emilia develops from a servant wife who speaks in whispers to an outspoken woman who ultimately solidifies Iago’s downfall. Her super objective evolves in much the same way as her character: it starts out meek, but then flourishes with a bold finish. At the Start Upon first glance, the reader is left to wonder about Emilia, as she is discussed only through Iago’s eyes in the first parts of the play. She is first introduced as a lazy cuckolding wife. “Come on, come on! You are pictures out of door, / Bells in your parlors, wildcats in your kitchens, / Saints in your injuries, devils being offended, / Players in your huswivery, and huswives in your bed.” (II.i.109-112) Upon Iago’s public lashing Emilia can only respond with this six-word sentence in her defense: “You shall not write my praise.” (II.i.115). Emilia seems to hardly muster up a response to her overbearing husband, if this can be called a response at all. In the complexities of love and marriage, comfort is a basic necessity between spouses. Emilia is not even comfortable enough to truly stick up for herself to her own husband, and barely manages to do so with the help of Desdemona. We know as readers of this classic tragedy that “love” in the normal definition does not exist when it comes to Iago and Emilia’s relationship, but one assumes that a wife of that time period would not stand for the criticisms Iago incessantly throws her way. Her entire life is centered on fulfilling a role that she is not appreciated to fill. This is when her super objective first comes into play. Emilia’s goal begins as a desire to avoid and escape her husband’s lashings, even if this is only with a meek phrase or two in protest. The Shift In the middle of the play our reader senses are prickled by Emilia’s seemingly motivated actions to please her husband. This all starts when she happens upon Desdemona’s cherished handkerchief lying on the ground: “I am glad I have found this napkin; / This was her first remembrance from the Moor. / My wayward husband hath a hundred times / Wooed me to steal it; but she so loves the token / (For he conjured her she should ever keep it) / That she reserves it evermore about her / To kiss and talk to. I’ll have the work ta’en out / And give’t Iago. What he will do with it / Heaven knows, not I; / I nothing but to please his fantasy.” (III.iii.290-299) Emilia realizes the importance of this handkerchief to her mistress Desdemona, but she also feels a desire to act on her husband’s wishes, despite the fact that he treats her like dirt and is using her as a pawn in his plan to trump Othello. While we cannot say that she is “in” on Iago’s schemes to bring upon the demise of Othello and those around him in a domino effect, it’s clear that at this point she is keen to serve his wishes, even if she is unsure of his motivations. It’s important to realize that Emilia’s act of giving the handkerchief to her husband is not to purposefully bring on the demise of Desdemona, but instead to simply please her husband. I would have to disagree with Eileen Abraham’s thoughts about Emilia wholly. “Indeed, it is freedom, not necessity, which initiates Emilia’s lies, both to herself and to Desdemona. She lies to Desdemona because she has chosen to live in denial of a truth which she cannot acknowledge: that she had the choice to act otherwise, and now, this denial has become the truth in which she lives.” (Abrahams) Emilia lies to Desdemona about the handkerchief because she doesn’t completely realize what is going on. She doesn’t yet know of Iago’s complete plan or his motivations. She does realizes that Iago is less than moral, but does not understand the extent to which he will act upon this handkerchief he’s asked her to filch. Her objective at this point in the play is to please her husband. After all, she innocently (and a little foolishly) claims she’ll just have the pattern copied. There’s no harm in that, right? Emilia’s Final Objective In the end, Emilia finally gains some bearing to stand on her own two feet after lying to Desdemona about the handkerchief. Once Emilia really figures out what Iago has done, she immediately reacts against him (she is no longer going to be his appeasing wife). As soon as Iago comes into the room Emilia says, “O, are you come, Iago? You have done well, / That men must lay their murders on your neck.” (V.ii.170-171). She is not shy to place the blame that he so deserved. Even though she stands alone in the midst of a dead Desdemona and four men, she is no longer hesitant to stand up for what is right (which in this case happens to be avenging Desdemona’s wrongful death). Her objective at this point is independence, something that has so far throughout the play eluded her as a character. In fact, once she finally obtains it, she must die for it at the hands of Iago’s sword. Emilia meets her end by ratting out Iago. She dies because she is defending Desdemona. Her independence allows her to do this, and leaves her as the unsung hero of this tragic play. The question of why Emilia’s objectives shift is a good one. Her transition is as apparent as evolution. She crawls, walks, and then rather than running, she soars. Without the help of Desdemona I don’t believe her objectives would ever have reached the final point they did, which was ultimately defiance and independence from her husband. Emilia’s story is crucial to the movement of the play, hence her growing and developing objective. Without her, the ending would be unsatisfying to the reader and ultimately sans morals. Because she drives the action of the denouement, she must finish with a bang (and ultimately, in Shakespeare’s mind, this equals death). Had she been independent and free from the grasps of Iago from the beginning, the reader (or audience, as Shakespeare intended) would be left hungry and wanting more at the conclusion. It served Shakespeare’s purpose for Emilia to start out as a mouse and finish like a hawk. Abrahams, Eileen. "I nothing know": Emilia's Rhetoric of Self-Resistance in Othello. Diss. University of Texas at Austin, 2004. Abstract. 12 Mar. 2009 <http://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=1700551>. "Emilia." Weblog comment. World Literature Thinkers S1. Feb. & March 2009 <http://worldliterature.ning.com/>. William, Shakespeare,. Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice. New York: Penguin Books, 2001.