Case 2: Zara

advertisement

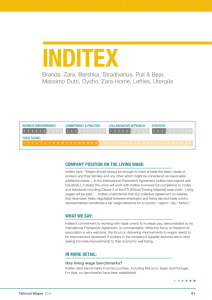

Case 2: Zara MRK2514 Markedsføring, Handelshøyskolen BI, høst 2007 Les artikkelen under og svar på de påfølgende spørsmål/oppgaver. Inditex The future of fast fashion Jun 16th 2005 | LA CORUÑA, SPAIN From The Economist print edition Spain's Inditex, the owner of the Zara chain of fashion stores, has bold but worrying expansion plans WHEN Spain's Crown Prince Felipe and Letizia Ortiz Rocasolano announced their engagement in 2003, the bride-to-be wore a stylish white trouser suit—which raised some eyebrows among those concerned with royal protocol. But within a few weeks, hundreds of European women were wearing something similar. Welcome to the world of instant fashion, in which a Spanish company is defying conventional wisdom and building a global brand: Zara. Instead of trying to create demand for new trends in the summer and winter seasons using the catwalks of fashion shows, Zara studies the demands of the customers in its stores and then tries to deliver an appropriate design at lightning speed. In the process, Zara has become the most profitable arm of Inditex, a holding company of eight retail brands, and one of the biggest success stories in Spanish business. From its beginnings in 1963 when Amancio Ortega Gaona, its founder, began to trade garments, Inditex has emerged as one of the world's fastest-expanding makers of affordable fashion clothing. Since 2000 it has more than doubled its number of shops to 2,240 by the end of last year, with sales of more than €5 billion ($7 billion). On June 13th, Inditex announced net profits up by 21% for the first quarter. How can Inditex thrive when Europe's entire textile industry is supposed to be under threat from cheap imports from China? At Inditex's heart is a vertical integration of design, just-intime production, delivery and sales. Some 300 designers work at the firm's head office in La Coruña in Galicia, a poor region in northern Spain. They are in daily contact with store managers to discover bestselling items. Fabric is cut in-house and then sent to a cluster of several hundred local co-operatives for sewing. When the finished product returns, it is ironed, carefully checked and wrapped in plastic for transport on conveyor belts to a group of giant warehouses. Twice a week lorries deliver the garments to other European countries and by aircraft to the rest of the world. Production is deliberately carried out in small batches to avoid oversupply. While there is some replenishment of stock, most lines are replaced quickly with yet more new designs rather than with more of the same. This helps to create a scarcity value. Shoppers cannot be sure that something that has caught their eye will appear in the store again—or can be found at another Zara store, even in the same city. On the other hand, they also know that everyone they meet will not be wearing it. The result is that Zara's production cycles are much faster than those of its nearest rival, Sweden's Hennes & Mauritz (H&M). An entirely new Zara garment takes about five weeks from design to delivery; a new version of an existing model can be in the shops within two weeks. In a typical year, Zara launches some 11,000 new items, compared with the 2,0004,000 from companies like H&M or America's giant casual-fashion chain, Gap. All of Zara's shops use point-of-sale terminals to report directly to La Coruña. On top of that, every evening store managers consult a personal digital assistant to check what new designs are available and to place their orders according to what they think will sell best to their customers. In this way, its store managers help shape designs. Zara does not employ star designers but often unknowns, many of whom are recruited directly from top design schools. Inditex is extremely clever in how it uses technology, says Andrew McAfee, a Harvard Business School specialist in the corporate use of information technology. The company keeps its technology simple—even a little old-fashioned—but as a result spends five to ten times less on information technology than its rivals. Zara is also more parsimonious with advertising and discounts. It spends just 0.3% of sales on ads, compared with the 3-4% typically spent by rivals. “We try to avoid markdowns”—now an almost permanent feature of American department stores—says José María Castellano Ríos, Inditex's deputy chairman. On June 13th the board appointed Pablo Isla to succeed him as chief executive. Mr Isla, a former co-chairman of Altadis, a Franco-Spanish tobacco company, is not a fashion man. His appointment followed a long search by head-hunters for someone able to manage a company that will inevitably become more complex as it grows and its supply chain lengthens. Mr Castellano says that over the next four years, Inditex plans to double in size to some 4,000 shops with sales of more than €10 billion. Most of this expansion will be in Europe, where he sees room for growth, especially in fashion-conscious Italy. Some investors are worried about this rapid pace. Over recent months the shares of H&M, a company with more modest plans for expansion, have performed better than those of Inditex. So far, Inditex has only 16 shops in America, the world's biggest market, and aims to gets its European expansion going before pushing hard on the other side of the Atlantic. By February, H&M had 76 stores in America, so it could get well ahead of its Spanish rival in that market. But H&M does things differently, including the hiring of star designers. Stella McCartney has been appointed to design its autumn collection, which will be sold in some of its European and American stores. Inditex's caution could be wise. Only two years ago it missed some of the year's main fashion trends. In their assessment of what went wrong in 2003, analysts at CSFB, an investment bank, identified issues of complexity and control as being among the causes—worrying for a company that likes to keep things simple. Even so, José Luis Nueno of IESE, a business school in Barcelona, believes the firm will grow successfully. Consumers have become more demanding and more arbitrary, so fast fashion is better suited to these changes, he argues. Inditex has proven that cheap and fast fashion can also be trendy and well presented. Zara's stores have won awards for their decoration and their shop windows. To smooth its growth, Inditex has opened a new distribution centre in Zaragoza. It has also begun to obtain some of its basic garments from low-cost countries, although the bulk of its production remains in Europe. China, for instance, accounts for just 12.5% of its production, less than that of rivals. Yet the further Inditex moves away from home, the trickier it will be to cater to instant-fashion whims. When Madonna gave a series of concerts in Spain, teenage girls were able to sport at her last performance the outfit she wore for her first concert, thanks to Zara. Although Mr Castellano insists that Inditex can be as nimble in other countries as it is at home, that could prove difficult. And if it stumbles, as Mr Castellano must know, the fickle world of fashion will be merciless. (Kilde: The Economist) Oppgave 1. Diskuter hvordan Zara bruker markedsinformasjon for å ta beslutninger med hensyn til sine kleskolleksjoner. Oppgave 2. Vurder Zara som merkevare: Hva er det Zara bygger sitt merke på? Hvordan differensiere de seg fra for eksempel Hennes & Mauritz? Dere skal ikke ta kontakt med bedrifter nevnt i dette caset eller andre bedrifter for å løse oppgaven. Pensumbok og forelesninger er hovedkildene for å besvare oppgaven på en god måte.