The invention of `the child`

advertisement

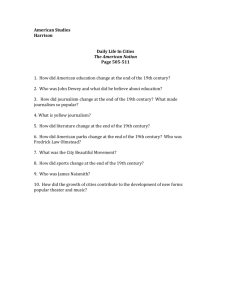

DID LIFE IMPROVE FOR LONDON´S CHILDREN? Victorian children witnessed the coming of the railways, and important changes in education and the way they spent their leisure time. But were they better off? The invention of 'the child' A child living in London at the end of the 19th century would have experienced a very different childhood to that of their grandparents born in the early years of the century. By 1899 London was an extremely crowded city, as more people came to live and find work in the capital. Many urban developments altered the lives of all children, but the experience of changing childhood in the 19th century was closely linked to family and social background. The life of a wealthy child was very different from that of a poor child. Wealthier children throughout the Victorian period were made aware of the suffering of the poor through the moral and religious education they received at Church Sunday schools. Those more comfortably off were encouraged to help those less fortunate than themselves by donating their money and time to charity. By the end of the 19th century, not only families but the government too had changed the way it treated children. At the time, more than a third of those living in England were under 15 years old. In an attempt to control the growing numbers of young people whilst, at the same time, protecting them from violence and poverty, the government introduced laws relating to the specific needs of children. This new attitude helped children to develop their own identity. They were no longer officially seen as 'miniature adults' but treated as a distinct social group with their own needs and interests which deserved special laws and treatment. Death and disease Victorian children were very close to death and suffering. In the 1830s almost half the funerals in London were for children under ten years old. Many people died from infections and diseases that we would rarely die of today, such as measles and scarlet fever. Children often experienced the death of a parent, brother or sister. If one of their parents died, wealthy children were expected to go into mourning and wear black clothing for up to a year. They may also have worn mourning jewellery such as a bracelet of plaited hair removed from the head of a dead relative. Poor children were more likely to suffer from death and disease. Many lived in dirty, crowded conditions and shared living accommodation with other families. They often lived in homes without heat where the only furniture was a heap of rags and straw. The lack of nutritious food, toilet facilities and the poor quality of drinking water resulted in serious cases of diarrhoea, typhoid and other infections. Raw sewage in the drinking water and the stench of the River Thames also made people feel almost constantly sick. Many people could not afford to visit a doctor or pay for medicines. Although the Great Ormond Street Hospital for sick children was founded in 1852, most sick children continued to be cared for at home in dirty and crowded conditions. Babies were especially likely to become ill and up to half of all poor children born in London died in their first year. Crime and punishment Children often experienced violence at home, school and work. Many poor children and orphans survived by joining street gangs and turning to crime and prostitution. In the novel Oliver Twist, Charles Dickens describes how children could become organised into pick pocketing gangs controlled by adult criminals. At the beginning of the 19th century, child criminals were punished in the same way as adults. They were sent to adult prisons, sometimes transported abroad for theft, whipped or even sentenced to death. In 1814 five child criminals under the age of fourteen were hung at the Old Bailey, the youngest being only eight years old. By the end of the 19th century, children who committed a crime were more likely to be sent to special youth prisons called Reformatory schools. By this time it was realised that adult prisons were bad for children and likely to encourage them to commit crimes when they became adults. Orphans London had many orphanages but places were usually given to orphans who had come from wealthy or respectable families. Many poor children whose parents had died were forced to live on the streets or in workhouses where conditions were extremely hard. By the end of the 19th century, poor orphans were beginning to enjoy an improved lifestyle. By this time many were living in special children's homes such as those established by Dr Barnardo. Children who suffered violence at home could also get help from the National Society of the Prevention for Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) set up in 1889. Work Poor children were forced to work from a very young age. Many earned a few pennies by becoming chimney-sweeps or working on the streets running errands, calling cabs, sweeping roads, selling toys or flowers and helping the market porters. Other children worked alongside their parents at home or in small, dark and dirty workshops sewing clothes, sacks or shoes. The industrial revolution had resulted in many children being employed in large factories. They were often responsible for operating dangerous machinery. Children who worked in factories suffered a hard life. The young girls who worked in the match factories run by Bryant and May endured long hours and poor pay. They worked worked with dangerous materials such as phosphorous that could cause a disease known as 'phossy jaw' that rotted their lower jaw. Many children worked as servants in the homes of richer families. In the 1850s one in nine of all female children over the age of ten years worked in domestic service. From the middle of the 19th century, charities tried to help poor street children by providing organised work for them. In 1866 John Groom set up the 'Watercress and Flower Girls' Christian Mission to provide a home and work for young and disabled flower sellers. From 1851 the London Shoe-Black Brigade, established by John MacGregor and Lord Shaftesbury, offered regular, better-paid, employment for children who made their living cleaning boots and shoes. Members of the London Shoe-Black societies wore a uniform with a coloured jacket indicating the area in which they worked. Those working in the City of London area wore red. In the evenings these children could attend lessons at the Ragged Schools. Education At the beginning of the 19th century, children were not required to go to school but, by 1899, all children up to the age of twelve officially had the opportunity of going to school. The sort of education they received depended very much on how wealthy their families were. Rich children could be educated at home by a private tutor or governess; boys were sent to boarding schools such as Eton or Harrow. The sons of middle-class families attended grammar schools or private academies. When Queen Victoria came to the throne in 1837, the only schools available for poor children were charity and church schools or 'dame' schools set up by unqualified teachers in their own homes. Ragged schools were introduced in the 1840s. They were established as charities and relied on people donating money and volunteering to become teachers. The President of the London Ragged School Union, founded in 1844, was Lord Shaftesbury. There were eventually 200 Ragged Schools in Great Britain providing an education for over 300,000 children who, as Charles Dickens noted, were 'too ragged, wretched, filthy, and forlorn, to enter any other place'. From 1870 the government introduced a system of education that enabled local authorities to set up schools paid for out of the rates or taxes. This meant that all children between the ages of five and thirteen could go to school if they paid about 2d (2 pence) a week. Many people could still not afford to send their children to school. The teaching in these schools was often poor and undertaken by monitors who were only about 12 years old. Classes were large and often had over 60 pupils. In 1891 the government introduced free education for all children up to the age of eleven. In 1899 the school-leaving age was raised to twelve. But many children still failed to attend school regularly, and continued to work during the day to help support their families. Leisure time London was an exciting city for children. Many spent much of their day on the streets where there was always some form of music and entertainment to enjoy, including organ grinders, acrobats and jugglers. Until 1868 children could even join the crowds watching the public hanging of criminals outside Newgate prison. Wealthier children with more leisure time could visit the zoo, museums, exhibitions and art galleries and from 1894 enjoy a ride on the revolving Great Wheel at Earls Court. At Christmas time they may have been taken to the theatre to watch a pantomime. At home they played with a range of toys from wax dolls to toy soldiers and train sets. There were many toy shops in London including Hamley's 'Noah's Ark' Toy Warehouse. In the Strand there was even a specialist toy arcade called Lowther's lined with many small toy shops selling a range of both expensive and cheap, mass-produced toys. From: Internet: www.museumoflondon.org.uk