Implications of Social Constructionism for Social Work

advertisement

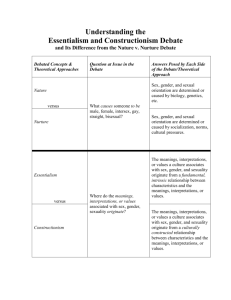

1 Implications of Social Constructionism for Social Work Fatih ŞAHİN Fatih Sahin is Associate Professor, Baskent University, Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Social Work, Turkey. E-mail: sahinf@baskent.edu.tr 2 Implications of Social Constructionism for Social Work According to the social constructionist approach, all knowledge is socially constructed. This construction includes our knowledge of what is reality. This paper provides an exploration of social constructionism as a basis for social work practice. A further purpose of this paper is to examine the implications of social constructionism for the practice of social work, with examples drawn from social work in Turkey. Key words: Social constructionism, social work, theory, Turkey Introduction Macht and Quam (1986) argued that the main goal of social work is to strengthen people’s ability to cope with tasks and problems that they face. Moreover, it is necessary to pay particular attention to promoting improvements in the environment to meet clients’ needs more adequately. Common definitions of social work refer to the change agent function of the profession and this particular function is regarded as the basic mission of social work. In modern times, scientific knowledge has become the basis for comprehending and explaining any given situation. Based on such a commitment, social work makes use of scientific theories, models, and approaches in accomplishing its mission. Knowledge and theoretical approaches, which help to define the dimensions of a given problem as well as the needs of clients, can affect the choice and nature of intervention. Having a theoretical basis for intervention is fundamental in social work practice. In recent years, a variety of theories have been developed in social and behavioral sciences and adopted by social work practitioners. Regardless of theoretical perspective or commitment, a social worker’s function as a change agent constitutes the primary basis for enabling people to cope with the demands of life. Theoretical perspectives as different as Freudian psychoanalysis, symbolic 3 interactionism, social exchange, family systems, human ecology, and social constructionism have all spawned versions and contributed to eclectic theories that strengthen the foundations of the profession (Chafetz, 1988). These theories, to some extent, concern themselves with understanding the reality of client. This endeavour is a crucial part of both theory and practice. However, we can distinguish between two polarised responses to the question of what constitutes the “nature of reality”. While the first advocates that truth is out there and independent of the individual, the second holds that truth is not independent of the individual but immanent in her/his beliefs and thoughts. The first approach to the nature of reality is commonly referred to as classical empiricism whereas the second, known as social constructionism, is the focus of this paper. It is my belief that mastering social constructionism, which supports the idea that reality can only be understood in relation to the beliefs, thoughts, and perceptions of an individual, will make a huge contribution to social work theory and practice. With its emphasis on individualisation, participation, self-determination, human rights, and social justice, a social constructionist approach can be an important tool in enabling and empowering client. Moreover, another implication of the social constructionist approach for social work is its goal in enabling clients to participate in the helping process, which is an important principle for accomplishing change. In this paper, the importance of social workers utilizing a theoretical approach is emphasized. Special attention is given to the social constructionist approach in fulfilling the mission of social work. The impact of social constructionism on social work is explored in the context of social work in Turkey. . Place of Theory in Practice 4 The aim of social work is to enrich society through orienting and empowering individuals and communities toward societal changes and new life styles. Social work is a profession and discipline that sees individuals and society supplementing and complementing each other and believes in complex, positive interactions of individuals and communities in solving human problems. The constructionist posits that knowledge should be in accordance with the needs of clients, and not other sources of power. Since all power groups produce knowledge in their favour, the function of social work is to support knowledge in favour of the client, which is not likely to be articulated unless there is professional support and guidance. Thus, it is necessary to provide opportunities for clients to narrate their stories in their own language. This is the best way of understanding the life and problems of clients and the role of social welfare institutions in their life. Consequently, the social worker is excluded from the position of the knowledgeable and key person in the solution of client’s problems. The client functions as an equal partner in the worker-client relationship. This gives a client an opportunity to express his or her own assessment of the situation. From a constructionist position, while trying to understand the client in the context of his or her ecology, different approaches should be utilized as well, because different theoretical approaches help us realize and appreciate different realities. In using different theoretical approaches, social workers should be aware of personal prejudices and assumptions as these may interfere with the ability to understand clients and develop treatment plans with them. In addition, social workers also need to realize that theories imply certain value preferences and political approaches (Dolgoff, 1981). Furthermore, theories also determine the direction of intervention. For example, in working with a juvenile offender, should a social worker use psychological or sociological theories? The theoretical frame we use to assess the situation will determine the type of intervention we choose. The social work profession, even at the turn of the millennium, 5 continues to discuss whether its basic treatment modality is individual treatment or its historical roots in social reform (Abramowitz, 1993; Haynes, 1998). Although it is clear that the mission of social work covers both of these approaches, within the framework of social constructionism, this may be interpreted as a result of the knowledge generated by groups that are not based on the social justice mission of social work. By neglecting social reform and concentrating more on individual treatment, social workers may suffer a lack of identity, in comparison with other helping professions that uses a broader lens in problem definition. Having presented the rationale for incorporating theory into social work practice, I will address the bases of social constructionism. Bases of Social Constructionism The paradigm of social constructionism is rooted in the philosophy of human experience, especially in the writings of Mannheim and Schutz. However, it grew in several fields, including sociology, social psychology, and social work. It has become the dominant approach to the study of social problems, within sociology in the United States, spawning dozens of articles and books and an on-going debate for the past 20 years (Franklin, 1995). Social constructionism draws on the works of Mead and Parsons within the social sciences (Parton, 2003). Deriving from social psychology (Gergen, 1985; Mead, 1934) and sociology (Berger & Luckmann, 1966), social constructionism can be defined as an approach to human inquiry, which encompasses a critical stance toward commonly shared assumptions. Such an approach holds the idea that widely accepted assumptions play an important role in reinforcing the interests of dominant social groups. Moreover, the way we understand the world is a product of a historical process of interaction and negotiation amongst groups of people. Thus, reality is not independent of history, culture, and context; in contrast, it is socially constructed (Houston, 2001). 6 Although there were earlier articulation on how reality and social sciences are shaped by the broader culture (Berger & Luckmann, 1966), the impetus for the development of social constructionism has been the social psychology of Gergen (1985), who elaborated on the social psychology of Mead (1934). Gergen (1985) characterises social constructionism as a movement, whose aim is to redefine commonly used psychological constructs (i.e., mind, self, and emotion) as socially constructed, rather than individually constructed processes. According to the social constructionist view, the generation of knowledge and ideas of reality are not sparked by individuals but through social processes (Gergen, 1994). If all reality is socially constructed and historically bounded, "knowledge is not something people possess somewhere in their heads, but rather, something people do together" (Gergen, 1985, 270). According to the long tradition of the sociology of knowledge and the “social construction of reality” (Berger & Luckmann, 1966), the so-called objective reality is, in fact, the product of social construction processes, under the influence of cultural, historical, political, and economic conditions. In The Social Construction of Reality, Berger and Luckmann (1966) proposed that all knowledge is socially constructed, including our knowledge of what “reality” is. Because people are born into a society and culture with existing norms and predefined patterns of conduct, definitions of “reality” are socially transmitted from one generation to the next and are further reinforced by social sanctions. These existing group definitions are learned and internalised through the process of socialisation. This knowledge gradually becomes a part of one’s own worldview and ideology. People rarely question their worldview and, unless they are challenged, they take their version of reality more or less for granted and think of it as the same for everyone else (Berger & Luckmann, 1966; Robbins, Chatterjee & Canda, 1998). This knowledge can be seen as the end product of a process of social construction, which provides the basis for our assumptions. Because such knowledge is socially constructed, it can 7 vary historically over time and differ across cultural groups, which hold diverse beliefs about human development and nature. It is also imperative to note that social constructionism is an approach that also emphasises language, meaning, and constructivism as a means whereby we interpret our experiences. Social constructionism suggests that reality is always filtered through human language (we cannot gain direct access to it). Furthermore, the relationship among language, objects, and actions is indeterminate, that is, there is no necessary connection between objects, actions, and states, and what they are called. Language does not reflect the world, but rather generates it (Witkin, 1999). The basic function of the language is to coordinate and regulate social life (Gergen, 1994). As Marcuse asserted, “in speaking their own language, people also speak the language of their masters, benefactors, advertisers” (Ingram, 1990, 86). According to this approach, we cannot perceive reality apart from our interpretations of it, whereas objectivists hold the idea that we make discoveries about the “real” world through building hypotheses and testing them. Constructionism states that our interests and values can never be disentangled from our observations; the observer is never neutral (Dean, 1993). Moreover, meanings are not inherent in objects or particular situations; rather we make meanings out of what we experience through interactions with others. Thus, social constructionists see numerous competing viewpoints of the world rather than one true view. Instead of grand narratives and universalising claims, which have characterised the realm of knowledge since the Enlightenment, knowledge is conceived of as being multiple, fragmentary, context-dependent, and local (Hare-Mustin, 1994). In sum, the unique feature of constructionism lies in the way it relates to individual differences among people. There is not “only one” proper technique or intervention to change human functioning. This philosophical perspective stresses the importance of designing specific intervention to meet the specific needs of the client (Ronen & Dowd, 1998). 8 Having discussed the foundations of social constructionism, I will elaborate on the application of social constructionism in social work, with examples drawn from the context of social work in Turkey. The Application of Social Constructionism in Social Work Social constructionism is closely related to the value system and mission of the social work profession and discipline. In parallel with what social constructionists argue, social workers question the structures and beliefs surrounding commonly accepted knowledge. Both try to understand the impact of history and culture on human development and functioning. Theoretical models addressing the problems we confront within society and their influence on the services provided are very important. For example, what is the mission of the centres for street children organized by social service organizations in Turkey? What are their goals? Is it about taking the children away from the streets or whether street children are included in the public sphere? To what extent do different social groups allow street children to participate actively in life? How much does each agency or group claim possession of the problem of caring for or educating street children? What are the value systems of each group and approach? Are these value systems congruent with social work mission and ethics? Are there any social group who would benefit from the existence of street children? These benefits include, but are not limited to, the benefits of claim-making, possessing the ownership of a socially defined problem, gaining credit and status from it, and becoming known as the “designated” workers with street children? An approach based on social constructionism will make social work practice more powerful. Both social constructionism and social work philosophy recommend supporting, facilitating, and legitimizing a variety of knowledge, traditions, and ways of personal and public expression. There is no need to limit the expression and flexibility of approaches in accordance with pre-set criteria (Gergen, 1994). Social workers believe that those who cannot 9 express themselves and their rights, including marginal groups, possess valuable opinions that must be taken into consideration. As Witkin (1999) indicates, social work should be a field in which views are expressed freely. Moreover, if a social worker is in a position to provide meaningful services, then the views expressed by clients, in their own language, will be of utmost importance to service providers. How can this be achieved? Encouraging marginalized persons to write their experiences in their own words, helping them write their stories, and sharing the gains of both workers and clients are some examples . Furthermore, to what extent should a client actively participate in the process of professional casework? Should a client have unconditional access to reports written, by a social worker, about his/her personal feelings, thinking, and the dynamics of other aspects of his/her life? A client’s view of reality may not be accurate, but the client should be the most appropriate person to express their view. The social constructionist view should not only be made use of in working with clients, but also be integrated as a basic value in social work. In this context, social workers have to be careful in using languages that are congruent with our professional identity. For example, the term disability. In Turkish, the word for disability, özür, is apparently in conflict with the basic values of social work. Özür connotes an incapability of doing something desirable and communicates a request to be excused. Therefore, this word contradicts a basic social work value, which is a belief in human potential and capacity to develop and find ways to meet goals, despite barriers or handicaps. How would it shape social work philosophy if this way of conceptualisation is not thought through clearly? What are the gains and losses for disabled persons and society in the use of this particular term? Can social workers find other words that more accurately reflect disabled persons’ realities and the client’s experience of reality? 10 Another linguistic example is self-determination. The Turkish word for selfdetermination is kendi kaderini tayin hakkı, which means determining one’s own fate. Now, what is the practical use of such a conceptualization in a society in which fate is believed to be God’s will rather than an individual’s will. The Turkish word for self-determination is not only a mis-translation but also connotes the opposite meaning of the term. Therefore, social workers need to find a new vocabulary to uphold basic social work values, which affirm the belief that people are inherently able to make rational choices and decisions and can be helped to meet their life goals, despite handicaps. Another term to consider is client. The Turkish word for client is müracaatçı, meaning a person who applies for any kind of service. But client in social work is not always an individual who applies for social service. A client can be a group (or even a community) that would need social work intervention. In that case, neither a group nor a community applies for social work intervention. According to Turkish understanding, social workers would not accept groups and communities as clients, thereby possibly excluding groups and communities from social work practice. Another connotation of the Turkish word for client is that the individual expects the service to which he/she applies to solve his/her problem. But in social work we do not solve people’s problems. Instead, we explore, with them, the choice of best options and actively involve them in decision making, with the social workers providing support, information, and assistance. Such a conceptualization of client in Turkish thinking seems to have been inspired by the medical model of practice, which has dominated social work for a long time in Turkey. It needs to be revised, using the frame of a new outlook, which emphasizes the person in his/her own environment. Still another terms for discussion is empowerment. The Turkish word for empowerment is güçlendirme, which connotes equipping of the person with power originating from the social worker. The English word empowerment also includes more or less the same 11 connotation, but in social work practice, the worker and client are seen as equal partners. Empowering a client means helping him/her to use the potential power that is available in him/her. Therefore, when we talk of empowerment in social work we have to move beyond the usual connotations and acquire an understanding of social work that is sui generis. Linguistically speaking, words may have positive or negative connotations. Intervention, in social work jargon, is a positive action, meaning an action that is designed for the benefit of the client by both the social worker and the client. However, the Turkish word müdahale has a negative connotation, implying that such an intervention does not seek the consent of the person. So, the connotations of the two words, “intervention” and “müdahale”, in English and Turkish respectively, are in contradiction with each other. Conclusion The use of social constructionist framework, as illustrated above, shows that social work is not necessarily objective or neutral. Hence, social workers should give attention to the following: 1. Use an approach that creates a more equitable relationship between social worker and client. The social constructionist approach is useful in clarifying the assumptions and values of social work practitioners. 2. The social constructionist approach facilitates the active solicitation of stories of clients, as narrated in their own words. This helps us understand the problems of clients, without always having to use any a priori theory. The life story of a client may not necessarily support existing theories. New or integrated theories may have to be created, which would be the contribution of social work practice to knowledge building. 3. Social constructionism provides information on how to create changes in professional practice, by giving greater priority to clientele values and perceptions. This approach can 12 be taken as the contemporary version of basic social work value of self-determination. This perspective allows clients to participate in the formulation of theories in practice. For social work to be influential, it should give priority to defining its identity and its components as inclusive of the client systems. The narration and language of clients should be used in problem definitions, with the understanding that the client is the most appropriate person to define the problem. A primary task for contemporary social work is to assign appropriate meaning to the concepts used in the field. This is the only way to make social work real. Though assessing and solving the problem from the perspective of clients may mean giving less attention to the interests of other parties and may, therefore, cause difficulty for professional practice, social workers should take the risks. Social workers must be prepared to face this conflict as the prerequisite for becoming fully effective and achieving their professional mission. 13 REFERENCES Abramovitz, M. (1993). Should all social work students be educated for social change. Journal of Social Work Education, 29(1), 6-11. Berger, P. & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality. New York: Doubleday. Chafetz, J. S. (1988). The gender division of labor and the reproduction of female disadvantage: Toward an integrated theory. Journal of Family Issues, 9(1), 108-131. Dean, R. G. (1993). Teaching a constructivist approach to clinical practice. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 8, 55-75. Dolgoff, R. L. (1981). Clinicians as policymakers. Social casework. The Journal of Contemporary Social Work, 62(5), 284-292. Franklin, C. (1995). Expanding the vision of the social constructionist debates: Creating relevance for practitioners. Families in Society, 76, 395-407. Gergen, K. J. (1985). The social constructionist movement in modern psychology. American Psychologist, 40, 266-75. Gergen, K. J. (1994). Realities and relationship: Soundings in social constructionism, Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Hare-Mustin, R. T. (1994). Discourses in the mirrored room: a postmodern analysis of therapy. Family Process, 33, 19-33. Haynes, K. S. (1998). The one hundred-year debate: Social reform versus individual treatment. Social Work, 43(6), 501-509. Houston, S. (2001). Beyond social constructionism: Critical realism and social work. British Journal of Social Work, 31, 845-861. Ingram, D. (1990). Critical theory and philosophy. New York: Paragon House. 14 Macht, M. W. & Quam, J. K. (1986). Social work: An introduction. Columbus, OH: Charles E. Merrill Publishing Company A Bell Howall Company. Mead, G. H. (1934), Mind, self, and society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Parton, N. (2003). Rethinking professional rractice: The contributions of social constructionism and the feminist “Ethics of Care”. British Journal of Social Work, 33(1), 1-16. Robbins, S. P., Chatterjee P. & Canda, E. R. (1998). Contemporary human behavior theory: A critical perspective for social work, Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Ronen, T. & Dowd T. (1998). A constructive model for working with depressed elders. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 30(¾), 83-89. Witkin, S. L. (1999). Constructing our future. (Editorial), Social Work, 44, 5-8.