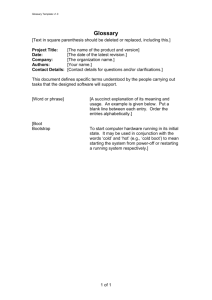

The Salamanca Corpus: Provincial Glossary (1787) A PROVINCIAL

advertisement