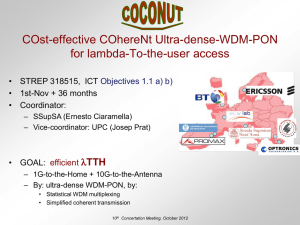

2. The approach

advertisement

Social Pacts on the Road to EMU: A Comparison of the Italian and Polish Experiences Guglielmo Meardi Abstract In the new EU member states tripartite, national level social pacts have been promoted as privileged instrument for a rapid and relatively painless attainment of the Maastricht criteria, following the example of many old member states in the 1990s and notably Italy. But such policy advice is not based on careful comparisons. The paper, by comparing Poland and Italy, undermines the dominant view that the failure of concertation attempts in Poland is mostly due to trade union politicisation. The comparative test with Italy, a country with equally politicised trade unions where, by contrast, important social pacts have been signed, suggests that divergent employers’ strategies and organisation are at least an equally important factor. Additionally, it provides a more mixed assessment of the Italian social pacts. Keywords: corporatism – European Union – Economic and Monetary Union – trade unions – interest politics Introduction In the literature on corporatism, concertation and social pacts in Europe there is a striking shortage of East-West comparative research (for a rare exception see Jankova and Turner 2004). The extensive production on post-communist countries has tellingly developed a distinct term (‘tripartism’) and by treating its object as a separate phenomenon from western European realities often falls into one of the following conceptual mistakes. In some cases, it assesses ‘tripartism’ using different benchmarks than in western Europe, that is, it ‘idealises’ western corporatism and, against such an idealised version, it unavoidably only points at eastern failures and deficiencies. In other cases, it builds on different, sometimes ad hoc explanatory models that use different variables, often of a cultural and/or political nature as against the more ‘mature’ institutional, strategic or economic ones that prevail in accounts of the western phenomenon. This article focuses on the case of social pacts as a specific historic configuration, emerged in the 1990s, of macro-level concertation, intended as tripartite (employers, unions and government) co-ordination of wage regulation and social and economic policy. The word concertation is used rather than ‘corporatism’, first because of the negative connotations of the concept in the Italian context, and second in order to include cases that achieve co-ordination without the structures considered as pre-requisites by ‘classic’ corporatist theory (Traxler 2004). After a discussion of the nature of social pacts across old and new member states (section 1) and a methodological note (section 2), I will here make the example of how the supposed ‘failure’ of Polish ‘tripartism’ is often explained through arguments that would not be well-suited in western Europe, with some serious analytical and normative drawbacks. It is notably the case of union ‘politicisation’, and it is most visible through an Italo-Polish comparison. The argument will be presented in sections 3 (presentation of 1 the two country’s situation), section 4 (a critique of the dominant explanation) and section 5 (the presentation of alternative explanations). In the conclusion, lessons for further research will be drawn. 1. EMU and social pacts, East and West The creation of a Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and the enlargement to eight, and in the future ten or more, post-communist countries have been the most important geopolitical changes for interest politics in Europe in the last years. While both changes have attracted a considerable amount of research, they have been very rarely studied jointly, forgetting that the new member states have no opt-out alternative and will have to join the EMU, which is expected for 2007 or little later. This article wants to develop the intuition by Kittel (2002) according to which EMU and enlargement would have a joint effect which is greater than the two taken separately. There is a large consensus on the fact that the introduction of a common currency, and the related convergence of monetary policies have important effects on interest representation and industrial relations. However, opinions could hardly be more diverse on the nature and direction of such effects. Three main alternative hypotheses can be distinguished. First, the ‘Anglo-Saxonisation’ hypothesis, which underlines the deregulatory effects of capital mobility, ECB monetarism, and budgetary restrictions (Boyer 2000). Second, the ‘Europeanisation’ hypothesis, which postulates a reconstitution, at the European level, of regulations which have been dismantled at the national one, whether in a functionalist (Schulten 2000), strategic (Traxler 2003; Ciccarone and Marchetti 2003) or contingent way (Marginson, Sisson and Arrowsmith 2003). Lastly, the possibility, apparently paradoxical, of ‘re-nationalisation’, due to the renewed suitability of concerted income policies in states which have lost control over the other tools (monetary, because of the Euro, and fiscal, because of the Growth and Stability Pact) of macro-economic management (Crouch 1998). The period between the Maastricht Treaty (1992) and the official inauguration of EMU (1999), during which as many as nine out of twelve future EMU members have engaged in concertative attempts, soon defined as ‘Social Pacts’ (Pochet and Fajertag 1997; 2000), had provided robust evidence in favour of the latter hypothesis. Some saw in them the reemergence, within the framework of long-term cycles, of neo-corporatist policies, illustrated by the image of a ‘corporatist Sisyphus’ (Schmitter and Grote 1997). Others have however noticed important differences between such social pacts and previous neocorporatist policies (Regini 1997 and 2003; Baccaro 2003; Rhodes 1997). There are also those who have criticised the new social pacts, on the basis not only of contingent arguments (e.g., on Italy, Mania and Sateriale 2002), but also of a general argument according to which re-nationalization of income policies under the Growth and Stability Pact regime would necessarily lead to, in sequence, a spiral of deflationary wage restraint, the increase of unemployment, and the weakening of trade unions (Martin 2000). According to such scenario, re-nationalisation, far from constituting an alternative to Anglo-Saxonisation of European societies, would only be an indirect path towards the same final outcome: a deregulated labour market with increased inequality. On the other hand, it has also been argued that given the co-ordination and imitation processes within the EU, re-nationalisation does not actually exclude Europeanisation, and may actually proceed alongside it (Dølvik 2000; Marginson and Sisson 2004). 2 Such divergent hypotheses and interpretations would require careful examination, but comparative studies on the argument have declined at the moment when EMU has been replaced by the enlargement as main topic of political debate. In fact, however, the enlargement confirms the importance of the issue, since social pacts, often under the label of ‘social dialogue’, have been strongly promoted by national and European agencies as privileged instrument for a rapid and relatively painless attainment of the Maastricht criteria in the new member states. For the first case of social pact on the Euro, in Slovenia, it has not even been necessary to wait until the official enlargement (EIRO 2004). On this ground, the comparative study of concertation experiences in the ‘old’ and ‘new’ member states, directly or indirectly related to EMU, appears to be timely for both applied and theoretical reasons. From the applied point of view, a deeper and more systematic comprehension of the first wave may provide useful learning material for the second, at least in order to avoid to be influenced by undue generalisations or trivialisations of western experiences. From the theoretical point of view, a comparison of countries with such different points of departure may provide the field for testing general hypotheses on the necessary conditions and the facilitating factors of neo-corporative policies, as well as their effects. 2. The approach A large part of debates on concertation and on different systems of wage determination is of economic nature, and has often taken as point of departure the well-known theory of a U relation between centralisation of wage determination and economic performance, first formulated by Calmfors and Driffill (1988), although implicitly present in the earlier works of other authors like Tarantelli. The argument by Calmfors and Driffill could be reformulated for the EMU, suggesting that re-nationalisation through social pacts, as intermediate level between European centralisation and company-level decentralisation, would be the worst possible option for member states. Further developments on this path have detected a number of additional conditions and functional equivalents (Traxler et al. 2001). This perspective, however, focussing only on the effects rather than on the origins, does not account for the whole complexity of the process. First, the econometric demonstration of it suffers of the limited number of observations, as clearly visible in Calmfors and Driffill’s study itself, and has therefore been so far unable to reach valid conclusions. Treating the EMU as a single observation case would then make comparative research within it impossible. Second, as it has been accurately argued (Traxler et al. 2001), the direct causal nexus cannot be with economic performance in general or with inflation, but only, more specifically, with unit labour costs trends. Using such latter variable as performance indicator, while very common, is however a normative choice (it treats as general interest what may be a class-related one), and a reductive one as it hides the issue of wage dispersion and treats as equivalent low-wage and high-productivity situations. A similar argument may be raised about the reduction of social expenditure as an additional parameter of ‘performance’. Finally, even if it were possible to reach, through comparative research, valid conclusions about the superior performance of one form of wage regulation, the lesson would be far from clear: transferability of socio-economic solutions across countries would remain an open issue, 3 and it is disputable that national social actors take decisions on the basis of comparative performance assessments. This study aims at integrating econometric analyses through an industrial relations approach based on in-depth case studies. Such choice implies an epistemological silence on the existence of any national or European ‘general interest’, and a focus on sociopolitical dynamics which may explain the forms of interest representation and, secondly, concertation. Although industrial relations assume an explicative priority of a structured antagonism of capital and labour, such approach does not deny that the empirical manifestations of interests are socially constructed through organisational, political and cultural practices. The actors are, therefore, at the centre of the analysis. Furthermore, it has been recently observed that the capital-labour relationship is only one of three interdependent arenas of exchanges (capital-labour, gender, welfare state) and that concertation actors take part in all three arenas (O’ Reilly and Spee 1998). As a consequence, interests may be composite and diverging even within labour or capital, and there are trade-offs between exchanges in the different arenas, but the understanding of these phenomena is still very limited. Applied to the topic of social pacts, such a broadly defined industrial relations approach will focus on the interactions and contamination between levels and arenas of exchange, and on the changing composition and interests of the actors, rather than on institutions (Hassel 2003). The article draws also on the large scientific production of post-communist studies. The actual working of tripartism has probably been the most studied aspect of central and eastern European industrial relations (probably because of its institutional relevance and visibility). Most studies have been critical towards such experiences, defined even as ‘illusory and neo-liberal corporatism’ (Ost 2000). A detached evaluation requires however such experiences to be compared with ‘really-existing’ corporatism of western countries rather than with ideal types. This research has used documentary analysis and interviews, and focussed on the timing of choices in a comparative perspective. It has studied how the modification of certain conditions has affected the existence and nature of concertation attempts. The method is qualitative, with a view of overcoming the problem of a limited number of observations through a deeper investigation of causal nexuses: it tries to open the ‘black box’ in which existing structures are transformed in collective identities, organisations and political choices. Specifically, the Italo-Polish comparison is based on official Tripartite Commission’s reports for Poland (MGPiPS 2003), and on secondary literature as well as CNEL (the institutional equivalent of a Tripartite Commission, although with a rather ‘ornamental’ function only) documentation for Italy. The period considered is 1989-2004. Importantly, the chronology is integrated by the longitudinal analysis of the social actors, including interviews with central union officers of CISL and Solidarity, as well as sector level representatives of CGIL and Solidarity for the metalworking and the banking sectors. Ongoing research which is being conducted at the company level has also shed light on the perception and implementation of concertation in the workplaces. 3. Double standards: union politicisation as a virtue in the West, as a vice in the East? Italy and Poland compared 4 Italy and Poland in 1992-2004 appear to be opposite cases with regard to the evaluation of corporatist success, but they share the supposed independent variable, that is trade union politicisation and links to political parties. On one side, Italy has been often portrayed in the last decade as one of the front-runners of the upsurge a new form of corporatism (called concertation or ‘social pact’), in spite of not displaying the traditional preconditions identified by classic corporatist theory and notably associational monopolies (e.g. Regini 1997, Baccaro 2003). On the other side, the dominant evaluation of Poland is heart-braking even for the usually poor Central European standards of façade tripartism: ‘the record of the Polish tripartite negotiations is clearly the poorest among [Poland, Czech Republic and Hungary]’ (Avdagic 2004a: 7). From a comparative perspective, the interesting point is that the dominant explanations of Polish failures (in the media, in political debates and in the scientific literature) focus on union politicisation as the main impeding factor. In general terms, the focus on union politics is related to the theoretical classic arguments about the functional distinction between corporatist and political governance, and the importance of associational monopoly (Panitsch 1979; Offe 1981). Yet also Italian unions are characterised by political origins (the so-called ‘Latin’ model) and commitment.1 This point begs the question: is really union politicisation the main obstacle to concertation? The Italian case In Italy the term of corporatism is still connected to the Fascist experience and therefore not popular. After the war, and until the 1990s, the country has actually been one of the furthest away from corporatist governance among western industrialised societies (Crouch 1993). Until the ‘hot autumn’ of 1968-69, trade unions were too weak to aspire to a political role, and the government was too conservative to involve a union side dominated by a communist confederation. After 1968-69, some attempts at central-level bipartite and tripartite regulation were made in 1975-78 and 1983-84, but with very scarce results. The main political orientation was not conducive to stable concertation: devaluation in the 1970s, and public deficits in the 1980s. However, in the 1980s some Italian regions saw the emergence of a sort of ‘micro-corporatism’ that somehow compensated for the enduring adversarial relations at the national level (Regini 1995). According to most accounts, the Italian season of macro-level concertation started on the 31st of July 1992, with a tripartite agreement abolishing the wage indexation system (scala mobile). Such season is generally explained through the deus ex machina of EMU constraints and the existence of pro-labour governments. This is only partially true for the 1992 agreement, though, which was the final outcome of tripartite negotiations that had started, on that issue, in 1989. In 1989 the Maastricht criteria had not yet been conceived, and in 1992 the Maastricht Treaty had not yet been ratified (the French referendum was pending). At that time, and still for other two years, the actual creation of EMU and the actual entrance of Italy were very much in doubt: deadlines were being postponed and the European constraints had not yet entered the political debate. The imperative of ‘entering Europe’ emerged in the media only in 1994-95. In 1992, Italians were still satisfied to have ‘entered Europe’ through the single market the year before. Politically, between 1981 and 1993 Italy was ruled by the same centre-left coalition, opposed by the Italian Communist Party (after 1991 relabelled Democratic Party of the Left, PDS) and by the main union confederation CGIL. CGIL actually ‘endured’ rather than approved the 5 agreement, and its leader Trentin needed to resign after signing it (the resignation was however rejected, according to a common Italian custom). What had changed in 1992 and may explain why an agreement had been finally reached is not union politics or EMU, but on the one hand the corruption scandals of ‘Bribeville’ shaking the government and, to an extent, large employers, and on the other the financial crisis that in a few weeks would have forced Italy out of the ERM. As a matter of fact, in the autumn of the same year the same government led by Amato introduced a unilateral pension reform that was fiercely opposed by all trade unions and by the PDS. The real ‘founding’ agreements of the Italian concertation came the year later, after Amato had been replaced by Ciampi with a parliamentary majority including the PDS. A tripartite agreement on the structure and criteria of collective bargaining was signed in July and another on plant-level union representation in December. Yet the process had started in 1992: according to the CGIL leader Trentin, the 1993 agreements would have not been achieved without the one of the pervious year (Trentin 1994). These agreements are widely considered as having been successful: the inflation rate declined very quickly, while real wages were broadly defended until 2001, and the subsequent bargaining rounds were smoother than in the past, with strike levels falling to record lows. In March 1994, few days before the new right wing party led by Silvio Berlusconi won the parliamentary elections, the three union confederations and the employer confederation Confindustria made the unusual public step of sending a formal letter to the Italian President to ask for guarantees on the respect of the 1993 agreements by the new government and the maintenance of concertation. Such declaration confirms the weight given at that time to the concertative instrument, but it did not achieve its goal. Newly elected Berlusconi did involve the social parties in long consultations during the Summer of 1994, but then tried to push through a unilateral pension reform that caused the largest industrial dispute since 1945 and contributed to the fall of the same government in December. In 1995, the new Dini government, supported by the Left, managed to accomplish the pension reform with the support of the unions. The final agreement on the issue was not signed by the employers and should not therefore considered as a tripartite success. However, the employers did not openly resist it either, and the decision not to sign it may be seen as tactical, in the perspective of future reform plans. It is under the centre-left government by Prodi that the Maastricht constraints become apparent and dominate the political debate. The EMU is in Italy a shared objective by most political and social forces and, as a shared objective, allows many issues to become positive-sum games. The EMU popularity at the time explains why the population, and the unions, supported in 1996 an exceptional, one-off extra seven points of income tax (with progressive corrections and the promise of refund) in order to bring the deficit in line with the Maastricht criteria. In 1998, against the expectation of many, Italy managed to enter the first group of EMU countries. However, concertation did not lead to important agreements or reforms in that period, apart from the Pact for Work of 1996 and an additional pension reform in 1997. In the meantime, the unions tried to defend their role in the concertation arena against the rising competition by a political party, Rifondazione Comunista, that tried to take on the representation of labour in the Parliament. This led to the apparent paradoxes of the unions opposing the government’s plan of working time reduction because it had been claimed by Rifondazione Comunista 6 instead of being agreed through concertation, and to a ritual general strike against the government in 1998, to which the same government ministers participated. After a parliamentary reshuffle, the new D’Alema government invested all its influence to achieve the 1998 ‘Christmas Pact’ on social and regional reforms, which may be seen as the apex of concertation but also as the beginning of the exit from it, through the enlargement of the table to many other actors and therefore the watering down of the same instrument. At the end of the 1990s, concertation was widespread but of little influence: according to one of the analysis, it was running the risk not only of dying, but – even worse! - of becoming a ritual (Salvati 2000: 475). Interestingly, this is the time when Italy had already entered the EMU: it seems therefore that the Maastricht criteria created demand for social pacts before accession, but not so much later (under the discipline of the Growth and Stability Pact), arguably because of the reduction of freedom for national governments. In 2001, Berlusconi came to power again, and this time he programmatically rejected concertation, preferring the idea of non-binding ‘social dialogue’. The new government split the unions and signed an agreement (the ‘Pact for Italy’) with CISL and UIL only in 2002, with the fierce opposition of CGIL in the streets. However, the actors did not abandon the idea of concertation overall. An agreement was signed by employers’ confederation and all unions, including the CGIL, in June 2003, and the new president of Confindustria (and Fiat chief executive) Montezemolo elected in May 2004 openly demanded a return of the government to concertation. Bipartite negotiations started on the reform of collective bargaining, but were soon abandoned by the CGIL. The Polish case Poland is unique in Central Europe in its delay in introducing tripartite bodies, advocated by ILO and EU, after the fall of communism. The Tripartite Commission was created only in 1994, after an original corporatist attempt to solve social conflicts related to privatisation through a ‘Pact for the Enterprise’ the year before, at the initiative of labour minister Jacek Kuroń, a charismatic former dissident and the main supporter of corporatism among Polish politicians. The Pact of 1993 came after a wave of strikes in 1992-93, after the ‘shock therapy’ had led to a sharp economic recession with industrial production falling by about 35%. Before 1992, no need for tripartism was felt in Poland because the most active trade union, Solidarity, was also the main force in the government. The union was expected to play the role of ‘protective umbrella’ for the government, and social negotiation should have occurred within the same government with no need for an additional body. This interpretation, to which Jankova and Turner (2004) subscribe, neglects however that Solidarity’s parliamentary arm did not actively defend labour interests in the 1989-1991 Parliament, and it was very much reduced after the parliamentary elections of 1991 when it only received 5% of the vote. There is no evidence of Solidarity political proposals to amend the hard neo-liberal policies of the government, while the same union, even if still clandestine, had had an enormous impact in the 1980s, by raising real wages, obtaining pension indexation in 1986, and blocking the first market-oriented reforms through a referendum in 1987. Only in May 1993 the parliamentary fraction of Solidarity decided to vote against the government, leading to its fall, but even in that occasion the majority of its MPs actually voted in favour of the ruling right-wing coalition. 7 Evaluations of the Tripartite Commission after 1994 have been sceptical since the beginning, similarly to the rest of central-eastern Europe (e.g. Reutter 1996, Mouranche 1996). In January 1995 it reached an important agreement on wages in the public sector, ending a strike in the health services. Agreements on public sector wages were also reached in 1996, but no longer since. In 1998 Solidarity refused to negotiate, and in 1999 the other union confederation, OPZZ, abandoned the Commission overall impeding its further work (at that time, each organisation had basically a veto power within the Commission). In order to reinvigorate the Commission and to avoid vetoes, a law was passed in 2001 to regulate its works. In 2002, the new labour minister, and later minister of economy and labour, Jerzy Hausner, an academic previously known for a neocorporatist orientation (e.g. Hausner 1994; Hausner, Pedersen and Ronit 1994), tried to lead it to a social pact on reforms, but it was eventually impeded by Solidarity’s opposition (Gardawski 2004). Eventually, in Summer 2004 Hausner contradicted its own neocorporatist orientation by proposing without previous consultation a radical reform of workplace industrial relation including the introduction of works councils. The paradoxical effect was to instigate bipartite dialogue between employers and unions, tactically allied against the government proposal. Evaluations of the Polish case range from very negative (e.g. Ost 2000: ‘illusory corporatism’) and more positive views depending on how corporatist performance is measured. ILO-oriented accounts insist that tripartism has been successful in limiting protest, and indeed strikes in post-communist Poland have constantly declined from a record-high in 1992-93 to an official (but not reliable) minimum of one strike in 2002, following the introduction of ‘tripartism’. The causal link between tripartism and strike behaviour is still to be proved, however, given that low strike propensity seems to characterise all post-communist societies regardless of corporatism (Bohle and Greskovits 2004). Jankova and Turner’s (2004) dissenting positive evaluation of Polish ‘social partnership’ (not entirely overlapping with tripartism) has been reached only at the cost of programmatically writing off outcomes from the analysis and only focussing on procedures and actor involvement. In this way, however, the success of corporatism becomes tautological and the issue of façade tripartism is by-passed – as façade and substance coincide. The argument on union politics has been formalised in the clearest way by Frieske and Machol-Zajda (1999: 13): the players (i.e. the unions) are interested in political, not economic pay-offs; and politically, pay-offs of rupture are always higher than those of co-operation. The fact that among all three sides of the Tripartite Commission of the time there were members of Parliament was seen as proof of the fact that the Commission was an element of the political, not corporatist order. In the Polish case, the difficulty is made insuperable by the fact that the two main confederations are on the two opposite sides of the political divide (Solidarity v post-communists, which with much approximation can be put as a Right-Left divide). In practice, the right-wing orientation of Solidarity would explain the Commission’s failures under ‘left-wing’ postcommunist governments (19931997 and 2001-to date), while the left-wing loyalty of OPZZ would have explained the failures under the right-wing government (1997-2001). Poland is actually not the only country with politically oriented trade unions on two separate sides of the political spectrum. Portugal, Belgium and the Netherlands (which all have reached some corporatist or social pact successes) are western examples, but we will 8 here focus on Italy, where union politicisation is very evident and, like in Poland, is rooted in community and social movement traditions, as exemplified by the importance of horizontal structures. 4. A critical assessment of the political explanation Three possible interpretations The theoretical argument of union politics as an obstacle to corporatism, then, works in Poland but not in Italy. Why? There are three possible explanations of the divergent paths of the two countries, of which two empirical (maintaining the validity of the theory) and one theoretical: - 1st explanation: union politics is fundamentally different in Poland and Italy - 2nd explanation: against the dominant view, Italian concertation has failed too - 3rd explanation: the theory of union politics as obstacle to corporatism is wrong or at least highly reductive. I will argue that there is some truth in explanations 1 and 2, but more in explanation 3. The test is based on the chronological analysis of tripartism and concertation in 19892004. The differences between Polish and Italian union politics It is customary to treat western and eastern trade unions as worlds apart. I was personally impressed ed by the opening question of a journalist of the main Polish newspaper interviewing me after Solidarity’s electoral victory of 1997: ‘what distinguishes Polish unions from the normal ones, like the Italian?’ (Gazeta Wyborcza, 24 September 1997). A close comparison with ‘really existing’ western trade unions forces however to revise some of the perceived distinctions. The divide between the two main confederations, CISL and CGIL (we exclude as politically less relevant the third confederation UIL, as we do in Poland for the FZZ) is less sharp than between Solidarity and OPZZ. On one side, CGIL-CISL-UIL have the past experience of a common federation in 1973-84, and their grassroots have often appealed to ‘unity of action’ since 1969. On the other side, Solidarity and OPZZ are kept apart by the memory of martial law, when some were jailed or fired, and others were rewarded for their loyalty. If this were not enough, they are also kept apart by an interminable legal dispute on the division of the former official unions’ possessions. Yet the concern with politics is not less sharp in Italy. In spite of a visible distinction due to the incompatibility between union and parliamentary mandate introduced by the unions themselves in 1969 (which does not exist in Poland, where in 1993-1997 about a fifth of the parliament were union representatives), Italian union leaders are important political figures and almost regularly move to senior political roles, like in the case of all CGIL general secretaries of the last twenty years (Lama, Pizzinato, Trentin and especially Cofferati, the protagonist of concertation in the 1990s). The CGIL leftist minority is even more politically engaged (its former leader Bertinotti is since 1994 the secretary of the Rifondazione Comunista party). The involvement of CGIL in politics was manifest in the public row between its leader Cofferati and the PDS leader D’Alema on the podium of the PDS Congress of 1997. After that event, Cofferati published a book of success whose title (‘Everyone to Their Job’) sounded like an excusatio non petita for his excessively 9 political profile (Cofferati 1997). In a similar way, OPZZ leader Manicki caused some tumult when he presented, and immediately after withdrew, his candidature to the presidency of the post-communist SLD party in March 2004. Although CISL is often portrayed as less politically characterised, the ‘revolving doors’ between union and politics operate for them in the same way (see the political careers of former leaders Carniti, Marini, D’Antoni.) For most of the 1990s both CISL and CGIL have been on the same side of the political divide, which might be interpreted as a structural difference from the Polish situation. Yet this is more an exception than their natural position, and cannot therefore be seen as a cause of corporatist successes. Between 1950 and 1993, with the only exception of 197679, CISL and CGIL’s majority have been on opposing sides (Christian Democrats and Communists, later Left Democrats), period which also includes the first important tripartite agreement (Amato 1992). This happened again, in more subtle ways, in 1999-03 after CISL leader D’Antoni started the political adventure of first the Grande CISL and then (after leaving CISL) the centrist Democrazia Europea party that supported Silvio Berlusconi’s right-wing government in 2001-04 (before shifting to the centre-left). In that period, CGIL leader Cofferati even suggested (maybe polemically) that a Polish-like union political bi-polarism (CISL on the Right, CGIL on the Left) was a realistic scenario for Italy (L’Espresso, 13th June 2002). On the other side, the forms of political involvement by the Polish unions are converging with the Italian practice. After the electoral defeat of Solidarity’s president Krzaklewski in 2000, Solidarity officially abandoned the political scene, and its situation looks now more and more similar to the Italian unions’ one. OPZZ too was marginalised within the post-communist party SLD in 2001 and had to turn to the Tripartite Commission to make its voice heard. Also, at the company level co-operation between the two unions is increasingly frequent, with a bottom-up pressure for unity of action that reminds the Italian situation of 1968-69. The striking similarity between Italian and Solidarity lies exactly in their political nature of social movements, including ideology, strong horizontal structures and concern for broad bargaining agendas (Meardi 2004, 2005). If in Poland the divide between Solidarity and OPZZ is biographic and cultural, Italian unions too have long been seen as rooted in distinct, Christian and communist, subcultures (Bedani 1995). Both Italian and Polish unions tend to represent interests that go beyond formal employment. Solidarity organised a referendum on popular privatisation in 1996, OPZZ tried to organise the unemployed, UIL to represent ‘citizens’ instead of workers, CGIL, CISL and UIL organised immigrants and stood by national unity during the farcical secession of Northern Italy in 1996. It is more appropriate to distinguish the degree of political power rather than of commitment. In this perspective, Advagic (2004b) has shown how unfavourable are unions’ links to political parties in the East as compared to the West. This stems in part in the unions’ incapacity to guarantee their constituency’s political loyalty. In 2001, for the first time, a majority of Solidarity members appear to have voted for the Left (CBOS 2001). Yet in this regard Italian unions are not much different from their Polish counterparts, as their control capacity is not much stronger and their political divide is not less sharp. In the 2001 elections, 50% of CISL members and 29% of CGIL members appear to have voted for the Right (Repubblica, 24 February 2002). Overall, stressing the 10 difference in political power is something radically different from stressing political involvement as such. Some authors have seen a link between the two, arguing that Solidarity’s social movement nature has been the cause of its weakness (Ost 2002). But this is not at all the dominant concern which is omnipresent in Polish media (Kozek 2000) and also recurrent in Polish specialist debates: Polish unions are portrayed as both too political and too strong, and this is seen as the obstacle to social pacts. Downgrading the Italian example? There are more empirical grounds to support the second explanation. If union political engagement is so important in Italy, then, if we maintain the classic theory, Italian concertation should actually be seen as a more superficial, politically contingent phenomenon than usually admitted (at least until 2001). There are arguments in favour of such an interpretation: concertation has really worked only in periods of pro-labour governments supported by both CISL and CGIL (1993-1994, 1995-1999). It has been fragile or unproductive under governments supported (or tolerated) only by CISL (199293 and 2001-02) or only by CGIL (1999-2001), and it has collapsed under anti-labour governments (1994, 2002-date). It is therefore to an extent dependent on the political cycle as it seems to be in Poland. Moreover, on some issues Italian corporatism has displayed its limits. While it has allowed the reform of collective bargaining and an effective income policy in 1993-2001 (elimination of inflation and overall defence of real wages), the new system has not worked in the important metalworking sector (where collective bargaining has been more adversarial than ever before) and it the South of the country (where company-level bargaining has not taken place). Yet the differences with Poland are macroscopic too. In a way, the metalworking sector may be seen as the exception confirming the rule, explained by its specific history, and the lack of company bargaining in the South may have its labour market reasons. With all its limits, in a comparative perspective Italian concertation remains a case of point in western Europe despite its more political unions than elsewhere. The most visible difference is on pension reforms. In Italy, unilateral reforms have been contested (1992, 2004) and in one case successfully rejected by the unions jointly (1994), while bargained reform, if gradual, has been successfully introduced (1995, 1997), although without the formal agreement of the employers. In each case unions were an important and essentially unitary actor despite of the deep political differences. In Poland, a much more radical, near ‘Chilean’ reform was introduced in 1998 in a completely unilateral way, with nearly no contestation from the unions (Guadiancich 2003). Actually, at no stage after 1989 one can detect a distinct union contribution to the path of socio-economic reforms in Poland.2 It is therefore not a functional explanation that might account for the divergent outcome of concertation attempts in the two countries. In spite of the different level of economic development, the issues on the table were similar (unemployment, inflation, pension reform), while the EMU constraints do not explain the difference: they affected Italy in a direct way in 1996-98, while the peak of concertation took place in 1992-95. Theoretical revision A way out of the puzzle may come from a more careful examination of the Polish path, together with a revision of the theory (explanation 3). The political cycle does explain 11 union opposition in pre-election periods (Solidarity opposition in 1997 and again in 2001, OPZZ opposition in 1999-2001). It does not explain the structural failure of the Tripartite Commission and the not unusual common standpoints between the two unions. Notably, it does not explain Solidarity’s opposition in 1998, when the government was right-wing. Moreover, an in-depth investigation into the actors’ views (Gąciarz and Pańków 2001) reveals that the negative view of OPZZ in 1998-2001 was shared by most Solidarity unionists, although formally Solidarity did not abandon the Tripartite Commission (which was not necessary because at the time the veto of one union was sufficient to prevent agreements). In the grassroots, Solidarity members were even more critical of the right-wing government than their OPZZ counterparts (CBOS 2001). An interesting, exceptional period to be considered is 1995-96, when the Chair of the Commission and Minister of Labour Bączkowski was uniquely ‘bipartisan’: he came from Solidarity but was a member of a post-communist government, and therefore enjoyed at least the respect of both unions. Today actors’ accounts portray the period of 1995-96 as a successful exception in the history of the Tripartite Commission. Yet if one looks at the actual production of the Commission, this seems rather an ex-post, possibly emotional (Bączkowski’s presidency was interrupted by his sudden death in young age) idealisation. The parties did meet and talk more than in other periods, but no major decisions were taken, and the wage agreement of summer 1996 was reached as a temporary truce in a situation which made even the liberal Gazeta Wyborcza newspaper speak of ‘class war’. Avdagic (2004a) confirms that the political cycle does not account for variation in tripartist practices in Central Europe. 5. An alternative explanatory framework I suggest looking for other more rigorous explanations of the divergent path of Italy and Poland, and therefore for variables that distinguish, rather than associate, the two countries. In particular, these are intra-organisational co-ordination, power balance among actors, and encompassingness. Vertical co-ordination Recent works by Traxler (1995, 2001, 2004) have underlined how vertical, intraorganisational co-ordination is at least as important as horizontal, inter-organisational one. While the unions are equally pluralistic in Poland and Italy, the vertical coordination capacity of both unions and employers’ associations differs sharply. In Italy, unions have been able to grant workers’ agreement to the pacts signed centrally, and both sides have on the whole implemented wage agreements at all levels. In Poland, the national-level wage agreements (when they are signed) remain completely irrelevant for the actual developments at company level, the only real bargaining level in the country (Urbaniak 1999). A number of interviews at different levels have shown that at the sector level the Commission’s recommendation for maximum wage increases are seen as completely irrelevant, while at the company level they are either unknown, or interpreted in different ways. In companies were they enjoy real bargaining leverage, unions use the recommendations as a starting point for a ‘minimum’ increase, on the top of which they make their demands. This is exactly the opposite of what the recommendations are meant to be. 12 As Traxler (2004) has argued, multiemployer collective bargaining is a ‘threshold’ required for the development of social pacts. In this regard, Poland is particularly weak (Kloc 2003). Yet, as Italy has shown in several occasions, the collective bargaining structure is not immutable. If this is the real obstacle to concertation, social and political actors may take action, for instance elaborating some forms of incentives or of erga omnes extension procedures. By contrast, according to Traxler, centralization (and therefore union political unity) is not that important because of the implementation problems it raises. In culturally divided societies like Poland and Italy, union divisions may be more a resource than a hindrance, as within one confederation the minority would have too many reasons not to comply with the leadership’s wishes. Relative power Corporatism has historically been a favoured strategy only after periods of labour activation and of excessive wage growth, and participation in it makes sense only for actors with an actual influence on the outcome. When governments and/or employers are strong enough to implement unilateral decisions there is not much need for it. On the other side, there are no real incentives to sign an agreement for organisations that have no veto power or real influence on the outcome: they would pay a political and consent price without actual rewards. In Italy, the unique situation in which concertazione emerged in 1992-93 was characterised (much more than by the often mentioned EMU constraints, that were not yet so present in the internal debate), by the sudden calamity of corruption scandals affecting both government and employers. As the only mass organisations on the whole unaffected by this calamity, the unions became the only availably support for political decisions. It is the (relative) weakness of the actors to have created the demand for concertation (Salvati 2000). At the end of 1998 government weakness and need for extraparliamentary support through a social pact occurred again: the D’Alema government was not born through democratic elections but only through the defection of some right-wing MPs, which explains the effort made to reach the ‘Christmas Pact’, the swan song of Italian concertation. In 2001, it is the government and the employers’ (with the new president of Confindustria D’Amato, expression of the SMEs and close to Berlusconi) to have changed their attitude to concertation, not the unions. On the other side, it is no wonder that the Tripartite Commission was introduced in Poland after the strike waves of 1992-93, but employers and the governments were soon very strong again after the elections of 1993 and the economic recovery associated with enduring high unemployment. Unlike in Hungary and Czech Republic, real wages have stagnated in Poland in the last decade, also because of unemployment close to 20%. The Polish Private Employers’ Confederation’s view of social dialogue is ‘dialogue is better than strikes’ (Gąciarz and Pańków 2001). The point then is, as long as there are no strikes in Poland, there is no need for dialogue. The same is valid for the government, as shown by its capacity to push through (although not to implement successfully) unilateral radical reforms in 1998 (Kolarska-Bobińska 2000). Degree of ‘encompassingness’ Corporatism is an effective strategy only when representation is encompassing enough to avoid major sectoral distortions and externalities. Polish unions are less encompassing than the Italian ones not so much because of the lower density rate (around 18% as 13 against 34%) but because of its distribution, concentrated on state sector and heavy industry. In the meanwhile, it is the exposed sector (where unions are very weak) where there is more concern with wage moderation. Paradoxically, union segregated nature according to craft, industry, gender or age may increase willingness to engage in corporatism (because of the need of political legitimacy), but decreases its effectiveness and viability. In this regard, however, a common problem in Italy and Poland is the male-dominated nature of tripartite bodies. In Poland, in 2001-2003 out of 42 representatives of employers and unions, only four have been women, and the only woman in the nine-person Presidium was the Private Employers’ Confederation’s president Henryka Bochniarz. In Italy, there was some outrage when no woman at all sat at the table of the tripartite negotiations of the first National Action Plan for the European Employment Strategy in 1998. Italian unions, in spite of increased ‘political correctness’, seem to have actually reduced their interest in gender equality with the increase in labour market differentiation (Beccalli and Meardi 2002). A similar problem occurs in terms of age, with the overrepresentation of elderly workers or even retired people (the majority of CGIL members) which has led to the effective defence of already retired workers but the underrepresentation of young workers rights in the case of pension reform in both countries. Conclusion To conclude, avoiding the short-cut of explaining corporatist failure through the political commitment of the unions prevents political and theoretical drawbacks. Politically, the dominant explanation is tantamount to ask the unions not to be themselves (voluntaristic requirement) and to give up some of the few resources they still have (political influence, loyalty, horizontal roots), whereas corporatism would actually benefit from stronger and more politically-responsible unions. What is rather needed is a reinforcement of unions at the sector level and of their implementation capacity, for instance, on the Italian example, through democratic practices of referenda. Theoretically, it would mean ignoring the deep changes in corporatist practice which make some of the classic preconditions obsolete. Interestingly enough, the need for theoretical change is confirmed, symmetrically, by the fact that the clear distinction between unions and politics in other countries seems to have become more of a problem than of a resource for corporatist agreements. Streeck (2003), drawing on Lehmbruch (1999), has explained the German failure to reach a social pact through the importance of parliamentary compromise in the Bundesrat, to which the unions are external and therefore, redundant. Also, Germany has one of the most segregated union scene, which according to our framework is a primary limit to effective concertation. In terms of research developments, the analysis suggests that more interest should be paid to the other actors (governments and employers), whose orientations and capacities, in both Italy and Poland, have been more effective predictors of concertation practice than the ever-blamed unions. The three factors identified as most important in the new generation of concertation, i.e. vertical co-ordination, class power balance and encompassingness, all need more comparative research and tests too. The increased pressure for social pacts on the eve of EMU enlargement may well offer a higher number of observations for this purpose. Matched, theoretically grounded contextualised comparisons may be of use for both ‘East’ and ‘West’: in this case, by dismantling easy, 14 common-sense explanations of the eastern failure, and by highlighting some overlooked weaknesses in the western case. References Avdagic, S. (2004a) ‘State-Labor Relations in East-Central Europe: Explaining Variations in Union Effectiveness’, Socio-Economic Review 2(3). Avdagic, S. (2004b) ‘The Weakness of Strong Ties: What’s Distinctive about Post-communist Labor Politics?’, Paper presented at the workshop on “The End of Labor Politics?”, Max-Planck Institut für Gesellschaftsforschung, Köln 17-18 June. Baccaro, L. (2003) ‘What is Alive and What is Dead in the Theory of Corporatism’, British Journal of Industrial Relations 41: 683-706. Beccalli, B. and G. Meardi (2002) ‘From Unintended to Undecided Feminism? Italian Labour’s Changing and Singular Ambiguities’, pp.113-31 in F. Colgan, and S. Ledwith (eds) Gender, Diversity and Trade Unions. An International Assessment. London: Routledge. Bedani, G. (1995) Politics and Ideology in the Italian Workers' Movement. Union Development and the Changing Role of the Catholic and Communist Subcultures in Postwar Italy. Oxford: Berg. Bohle, D. and B. Grekovits (2004) ‘Capital, Labor and the Prospects of the European Social Model in the East’. Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies Working Paper, Harvard University. Harvard. Boyer, R. (2000) ‘The Unanticipated Fallout of the European Monetary Union: The Political and Institutional Deficits of the Euro’, pp.24-88 in C. Crouch (ed) After the Euro. Shaping Institutions for Governance in the Wake of European Monetary Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Calmfors, L. and J. Driffill (1988) ‘Bargaining Structure, Corporatism and Macroeconomic Performance’, Economic Policies 6: 13-61. CBOS (2001) Związki zawodowe w zakładach pracy. Warsaw, komunikat. Ciccarone, G. and E. Marchetti (2003) ‘Trade Union Density and Wage Moderation in the European Monetary Union’, 173-205 in M. Baldassarri and B. Charini (eds) Studies in Labour Markets and Industrial Relations. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Cofferati, S. (1997) A ciascuno il suo mestiere. Milan: Mondadori. Crouch, C. (1993) Industrial Relations and European State Traditions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Crouch, C. (1998) ‘Non amato ma inevitabile il ritorno al neocorporatismo’, Giornale di diritto del lavoro e relazioni industriali 1: 55-79. Dølvik, E. (2000) ‘Economic and Monetary Union: Implications for Industrial Relations and Collective Bargaining in Europe’, ETUI Discussion and Working Paper 01/04. Brussels: ETUI. EIRO (2004) ‘National-level Tripartism and EMU in the New EU Member States and Candidate Countries.’ www.eiro.eurofound.eu.int. European Foundation for the Improvement of Working and Living Conditions (2003) Social Dialogue and EMU in the Acceeding Countries. Luxembourg: EC. Fajertag, G. and P. Pochet (eds) (1997) Social Pacts in Europe. Brussels: ETUI. Fajertag, G. and P. Pochet (eds) (2000) Social Pacts in Europe – New Dynamics. Brussels: ETUI. Frieske, K.W. and L. Machol-Zajda (1999) ‘Instytucjonalne ramy dialogu społecznego w Polsce: szanse i ograniczenia’, pp. 7-18 in K.W. Frieske, L., Machol-Zajda, B. Urbaniak and H. Zarychta (eds) Dialog społeczny. Zasady, procedury i instytucje w odniesieniu do podstawowych kwestii społecznych. Warsaw: IPiSS. Gąciarz, B. and W. Pańków (2001) Dialog społeczny – fikcja czy szansa. Warsaw: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. Gardawski, J. (2004) ‘Social Dialogue in Poland’. Paper presented at the IRRA Annual Meeting, San Diego 3-5 January. Guadiancich, I. (2003) ‘Why Did the Pension System Reform in Poland and Slovenia Lead to Different Outcomes?’, Est-Ovest 6: 41-78. Hall, P. and D. Soskice (eds) (2001) Varieties of Capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Hassel, A. (2003) ‘The Politics of Social Pacts’, British Journal of Industrial Relations 4: 707-26. Hausner, J. (1994) Negotied Strategy in the Transformation of Post-Socialist Economy. Cracow: Cracow Academy of Economics. 15 Hausner, J., O.K. Pedersen, and K. Ronit (1994) ‘Emergence of New Forms of Associability and Collective Bargaining in Post-Socialist Countries’, EMERGO 1(1). Jankova, E. and L. Turner (2004) ‘Building the New Europe: Western and Eastern Roads to Social Partnership’, Industrial Relations Journal 35(1): 76-92. Kittel, B. (2002) ‘EMU, EU Enlargement, and the European Social Model: Trends, Challenges and Questions’, MPIfG Working Paper 02/1. Köln. Kloc, K. (2003) ‘Poland: Confined to the Public Sector’, pp. 317-40 in Y. Ghellab and D. VaughanWhitehead (eds) Sectoral Social Dialogue in Future EU Member States: The Weakest Link. Budapest: ILO. Kolarska-Bobińska, L. (ed) (2000) The Second Wave of Polish Reforms. Warsaw: Institute of Public Affairs. Kozek, W. (2000) Destruktorzy. Obraz związków zawodowych w tygodnikach politycznych w Polsce. Paper presented at the Congress of the Polish Sociological Association, Rzeszów, 20-23 September. Lehmbruch, G. (1999) ‘Institutionelle Schranken einer ausgehandelten Reform des Wohlfahrtsstaates: Das Bündnis für Arbeit und seine Erfolgsbedingungen’, pp. 89-112 in R. Czada and H. Wollmann (eds) Von der Bonner zur Berliner Republik: 10 Jahre deutsche Einheit. Leviathan, Sonderheft 19. Mania, R. and G. Sateriale (2002) Relazioni pericolose. Bologna: Il Mulino. Marginson, P. and K. Sisson (2004) The Europeanisation of Industrial Relations? A Multi-level System in the Making. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Marginson, P., K. Sisson and J. Arrowsmith (2003) ‘Between Decentralization and Europeanization: Sectoral Bargaining in Four Countries and Two Sectors’, European Journal of Industrial Relations 9(2): 163-87. Martin, A. (2000) ‘Social Pacts, Unemployment and EMU Macroeconomic Policy’, pp.365-400 in G. Fajertag and P. Pochet (eds) Social Pacts in Europe – New Dynamics. Brussels: ETUI. Meardi, G. (2002) ‘The Trojan Horse for the Americanization of Europe? Polish Industrial Relations Toward the EU’, European Journal of Industrial Relations 8(1): 77-99. Meardi, G. (2004) ‘Modelli o stili di sindacalismo in Europa?’, Stato e Mercato 71: 207-36. Meardi, G. (2005) ‘The Legacy of ‘Solidarity’. Class, Democracy, Culture and Subjectivity in the Polish Social Movement’, Social Movement Studies, 4 (forthcoming). MGPiPS (2003) Trójstronna komisja do spraw społeczno-gospodarczych. Warsaw: MGPiPS. Mouranche, S. (1996) Doświadczenia trójstronności w Europie Środkowej. Warsaw: IPiSS. Offe, C. (1981) ‘The Attribution of Political Status to Interest Groups’, pp.123-58 in S.D. Berge (ed) Organizing Interests in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. O’ Reilly, J. and C. Spee (1998) ‘The Future of Regulation of Work and Welfare: Time for a Revised Social and Gender Contract?’, European Journal of Industrial Relations 4(3): 259-81. Ost, D. (2000) ‘Illusory Corporatism in Eastern Europe: Neoliberal Tripartism and Postcommunist Cladd Identities’, Politics and Society 28(4): 503-30. Ost, D. (2002) ‘The Weakness of Strong Social Movements: Models of Unionism in the East European Context’, European Journal of Industrial Relations 8(1): 33-51. Panitsch, L. (1979) ‘The Development of Corporatism in Liberal Democracis’, pp.119-45 in P. Schmitter and G. Lehmbruch (eds) Trends towards Corporatist Intermediation. London: Sage. Regini, M. (1995) Uncertain Boundaries. The Social and Political Construction of European Economies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Regini, M. (1997) ‘Still Engaging in Corporatism? Recent Italian Experience in Comparative Perspective’, European Journal of Industrial Relations 3(3): 259-78. Regini, M. (2003) ‘I mutamenti nella regolazione del lavoro e il resistibile declino dei sindacati europei’, Stato e Mercato, 1. Reutter, W. (1996) ‘Trade Unions and Politics in Eastern and Central Europe: Tripartism without Corporatism’, pp.137-57 in P. Pasture, J. Verberckmoes, and H. De Witte (eds) The Lost Perspective? Aldershot: Ashgate, Vol.2. Rhodes, M. (1997) ‘Globalization, Labour Market and Welfare State: A Future of “Competitive Corporatism”’, EUI Working Paper RSC 97/36. Florence. Salvati, M. (2000) ‘Breve storia della concertazione all’italiana’, Stato e Mercato 3: 447-76. Schmitter, P. and J.R. Grote (1997) ‘The Corporatist Sisyphus: Past, Present and Future’, EUI Working Paper SPS 97/4. Florence. 16 Schulten, T. (2000) ‘The European Metalworkers’ Federation on the Way to a Europeanisation of Trade Unions and Industrial Relations’, Transfer 1: 93-102. Streeck, W. (2003) ‘No Longer the century of Corporatism. Das Ende des “Bündniss für Arbeit”’, MPIfG Working Paper 03/4. Cologne. Traxler, F. et al. (2001) National Labour Relations in Internationalised Markets. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Traxler, F. (2003) ‘Bargaining, State Regulation and the Trajectories of Industrial Relations’, European Journal of Industrial Relations 9(2): 141-61. Traxler, F. (2004) ‘The Metamorphosis of Corporatism: From Classical to Lean Patterns’, European Journal of Political Relations (forthcoming). Trentin, B. (1994) Il coraggio dell’utopia. La sinistra e il sindacato dopo il taylorismo. Milano: Rizzoli. Urbaniak, B. (1999) ‘Ocena efektywności negocjacji trójstronnych w zakresie wynagrodzeń’, pp.19-41 in K.W. Frieske, L. Machol-Zajda, B. Urbaniak and H. Zarychta (eds) Dialog społeczny. Zasady, procedury i instytucje w odniesieniu do podstawowych kwestii społecznych. Warsaw: IPiSS. 1 Broadly speaking, CGIL has communist-socialist origins, CISL Christian-Democratic, UIL socialdemocratic. 2 With the possible exception of the union of nurses on the health reform in 1998 and 2002 – interestingly enough, however, a non-affiliated trade union. 17