A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings

advertisement

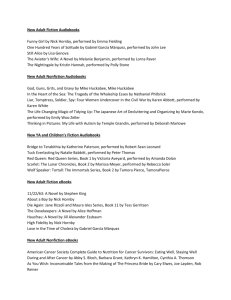

A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings Gabriel García Márquez Context Gabriel García Márquez was born in 1928 in a small village in Colombia near the Caribbean coast. His parents were poor, so his maternal grandparents raised him, and he would later claim that he drew much of his literary inspiration from his grandmother’s storytelling. After attending college and law school, he began a successful career as a journalist but continued to pursue his interest in writing fiction. García Márquez published his first collection of short stories, Leaf Storm, which included “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings,” in 1955. The book was an immediate success, and he consequently left journalism to devote himself to becoming “the best writer in the world,” as he later told an interviewer from the Paris Review. García Márquez later won international acclaim for his first novel, the modern classic One Hundred Years of Solitude, in 1967. Subsequent novels such as Love in the Time of Cholera (1985) and The General in His Labyrinth (1989) established García Márquez as one of the most notable writers of the twentieth century. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982. García Márquez’s literary style draws heavily from European gothic writers such as Franz Kafka, who famously turned his one of his characters, Gregor Samsa, into a giant insect in “The Metamorphosis” (1915). American novelist William Faulkner has been cited as a forerunner to García Márquez as well, especially in the way Faulkner grounds his highly experimental novels in the grotesque details of a particular local culture. García Márquez’s own development of the magical-realist genre has had enormous influence on writers throughout the world, especially in Central and South America. In fact, magical realism has since become one of the signature fictional genres of Latin American writers, including Argentina’s Jorge Luis Borges, Chile’s Isabel Allende, and Peru’s Mario Vargas Llosa. In addition to writing, García Márquez has also served as one of Latin America’s most distinguished diplomats and mediators. Although he’s never held any public office, he’s worked tirelessly behind the scenes to mediate disputes between the government, leftist guerillas, right-wing paramilitaries, and the drug cartels during Colombia’s decades-long civil war. Friends with both Cuban leader Fidel Castro and former U.S. president Bill Clinton, García Márquez also sought to bridge the gap between the two countries in the 1990s, which strengthened his reputation as a peacemaker. Many have hailed him as Colombia’s only voice of reason and the country’s best hope for peace. The almost cultish reverence for “Gabo,” as Colombians affectionately call him, has transformed García Márquez into both a national and Latin American icon. Also known in Colombia as El Maestro and Nuestro Nobel (our Nobel winner), he actually spends most of every year living abroad in Mexico City, Havana, Paris, Barcelona, and Los Angeles, where his son, Rodrigo Garcia, works as a Hollywood director. Plot Overview One day, while killing crabs during a rainstorm that has lasted for several days, Pelayo discovers a homeless, disoriented old man in his courtyard who happens to have very large wings. The old man is filthy and apparently senile, and speaks an unintelligible language. After consulting a neighbor woman, Pelayo and his wife, Elisenda, conclude that the old man must be an angel who had tried to come and take their sick child to heaven. The neighbor woman tells Pelayo that he should club the angel to death, but Pelayo and Elisenda take pity on their visitor, especially after their child recovers. Pelayo and Elisenda keep the old man in their chicken coop, and he soon begins to attract crowds of curious visitors. Father Gonzaga, the local priest, tells the people that the old man is probably not an angel because he’s shabby and doesn’t speak Latin. Father Gonzaga decides to ask his bishop for guidance. Despite Father Gonzaga’s efforts, word of the old man’s existence soon spreads, and pilgrims come from all over to seek advice and healing from him. One woman comes because she’d been counting her heartbeats since childhood and couldn’t continue counting. An insomniac visits because he claims that the stars in the night sky are too noisy. The crowd eventually grows so large and disorderly with the sick and curious that Elisenda begins to charge admission. For the most part, the old man ignores the people, even when they pluck his feathers and throw stones at him to make him stand up. He becomes enraged, however, when the visitors sear him with a branding iron to see whether he’s still alive. Father Gonzaga does his best to restrain the crowd, even as he waits for the Church’s opinion on the old man. The crowd starts to disperse when a traveling freak show arrives in the village. People flock to hear the story of the so-called spider woman, a woman who’d been transformed into a giant tarantula with the head of a woman after she’d disobeyed her parents. The sad tale of the spider woman is so popular that people quickly forget the old man, who’d performed only a few pointless semimiracles for his pilgrims. Pelayo and Elisenda have nevertheless grown quite wealthy from the admission fees Elisenda had charged. Pelayo quits his job and builds a new, larger house. The old man continues to stay with them, still in the chicken coop, for several years, as the little boy grows older. When the chicken coop eventually collapses, the old man moves into the adjacent shed, but he often wanders from room to room inside the house, much to Elisenda’s annoyance. Just when Pelayo and Elisenda are convinced that the old man will soon die, he begins to regain his strength. His feathers grow back and he begins to sing sea chanteys (sailors’ songs) to himself at night. One day the old man stretches his wings and takes off into the air, and Elisenda watches him disappear over the horizon. Character List The Old Man - An old man with wings who appears in Pelayo and Elisenda’s yard one day. Filthy and bedraggled, the old man speaks a foreign language that no one can understand. His wings and unintelligible language prompts some people to believe that he’s a fallen angel and the church to believe he’s a Norwegian, even though he seems oblivious to nearly everything that happens around him. By the end of the story, the old man has recovered enough to fly away, exiting Pelayo’s and Elisenda’s lives as suddenly as he’d entered. Pelayo - Elisenda’s husband and the discoverer of the old man. Pelayo is an ordinary villager, poor but grudgingly willing to shelter the winged old man in his chicken coop. Pelayo guards the old man from harm, humbly consults the village priest, and has the sense to resist the more extravagant advice he receives from the other villagers. Pelayo, however, does not want to take care of the man indefinitely and doesn’t feel bad using the old man to get rich. Elisenda - Pelayo’s wife. Elisenda convinces Pelayo to charge villagers to see the old man but later considers him to be a nuisance. A practical woman, she primarily concerns herself with the welfare of Pelayo and their child and is therefore relieved when the old man finally leaves. Father Gonzaga - The village priest. As an authority figure in the community, Father Gonzaga takes it upon himself to discern whether the old man is an angel as the townsfolk believe or just a mortal who just happens to have wings. Father Gonzaga is skeptical that the dirty old man could really be a messenger from heaven, but he dutifully reports the event to his superiors in the church. As he waits for the Vatican’s reply, he does his best to restrain the enthusiasm and credulousness of the crowd of onlookers. The Neighbor Woman - Pelayo and Elisenda’s bossy neighbor. The supposedly wise neighbor woman actually seems more like a silly know-it-all than a true counselor and is the first to suggest that the old man is a crippled angel. She tells Pelayo to club the old man to death to prevent him from taking Pelayo and Elisenda’s sick baby to heaven. The Spider Woman - A freak-show attraction who visits the village. Punished for the sin of disobeying her parents, the spider woman now has the body of an enormous spider and the head of a sad young woman. The clear moral of the woman’s story draws gawking villagers away from the old man, who is unable to offer the crowds such a compelling narrative. Analysis of Major Characters The Old Man The old man, with his human body and unexpected wings, appears to be neither fully human nor fully surreal. On the one hand, the man seems human enough, surrounded as he is by filth, disease, infirmity, and squalor. He has a human reaction to the people who crowd around him and seek healing, remaining indifferent to their pleas and sometimes not even acknowledging their existence. When the doctor examines him, he is amazed that such an unhealthy man is still alive and is equally struck by how natural the old man’s wings seem to be. Such an unsurprised reaction essentially brings the “angel” down to earth, so any heavenly qualities the old man may have are completely obscured. However, the narrator seems to take the old man’s angelhood for granted, speaking of the “lunar dust” and “stellar parasites” on his wings, and the old man’s “consolation miracles,” such as causing sunflowers to sprout from a leper’s sores, seem genuinely supernatural. In the end, the old man’s true nature remains a mystery. Pelayo Although Pelayo is kinder to the old man than the other villagers, he is certainly no paragon of compassion and charity. He doesn’t club the old man as the neighbor woman suggests, but he does pen the supposed angel in his chicken coop and charge admission to the crowds of curious sightseers. Pelayo is primarily concerned with his family and sick child and is content to leave the theoretical and theological speculations to Father Gonzaga. His decision to shelter the old man and take some responsibility for him, however, suggests that he isn’t as cold or heartless as he might seem. By allowing the old man to stay, Pelayo also invites mystery, wonder, and magic into his life. Elisenda Elisenda is a perfect match for her husband, Pelayo, being equally ordinary and concerned with practical matters. If anything, Elisenda is the more practical of the two because she suggests charging admission to see the “angel.” Despite the many material advantages the old man brings, Elisenda’s attitude toward him is primarily one of annoyance and exasperation. Once the old man’s usefulness as a roadside attraction dwindles, Elisenda sees him only as a nuisance. Indeed, the old man becomes so troublesome to her that she even refers to her new home—purchased with proceeds from exhibiting the old man—as a “hell full of angels.” The old man becomes so ordinary in Elisenda’s eyes that it isn’t until he finally flies away that she seems to see him for the wonder he is. Elisenda watches him fly away with wistfulness, as if finally realizing that something extraordinary has left her life forever. Themes, Motifs, and Symbols Themes The Coexistence of Cruelty and Compassion “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings” wryly examines the human response to those who are weak, dependent, and different. There are moments of striking cruelty and callousness throughout the story. After Elisenda and Pelayo’s child recovers from his illness, for example, the parents decide to put the old man to sea on a raft with provisions for three days rather than just killing him, a concession to the old man’s difficult situation but hardly a kind act. Once they discover that they can profit from showcasing him, however, Pelayo and Elisenda imprison him in a chicken coop outside, where strangers pelt him with stones, gawk at him, and even burn him with a branding iron. Amidst the callousness and exploitation, moments of compassion are few and far between, although perhaps all the more significant for being so rare. Even though he is taken in only grudgingly, the old man eventually becomes part of Pelayo and Elisenda’s household. By the time the old man finally flies into the sunset, Elisenda, for all her fussing, sees him go with a twinge of regret. And it is the old man’s extreme patience with the villagers that ultimately transforms Pelayo’s and Elisenda’s lives. Seen in this light, the old man’s refusal to leave might be interpreted as an act of compassion to help the impoverished couple. García Márquez may have even intended to remind readers of the advice found in Hebrews 13:2 in the Bible: “Be not forgetful to entertain strangers: for thereby some have entertained angels unawares.” Motifs Prosperity Pelayo and Elisenda’s newfound prosperity is the physical manifestation of the magic and wonder the old man brings to their lives. As the story opens, the couple lives in an almost comical state of poverty as swarms of crabs invade their home. Even worse, their young son is deathly ill. The old man, however, brings hundreds of pilgrims who don’t mind paying Pelayo and Elisenda a small fee for the privilege of seeing him. The proceeds bring Pelayo and Elisenda a new house, a new business, and more money than they know how to spend. This remarkable turn in fortune happens so gradually that Pelayo and Elisenda don’t really see how remarkable it is. Elisenda even refers to her new home as a “hell full of angels” once the old man is allowed inside after the chicken coop collapses. Symbols Wings Wings represent power, speed, and limitless freedom of motion. In the Christian tradition, angels are often represented as beautiful winged figures, and García Márquez plays off of this cultural symbolism because, ironically, the wings of the “angel” in the story convey only a sense of age and disease. Although the old man’s wings may be dirty, bedraggled, and bare, they are still magical enough to attract crowds of pilgrims and sightseers. When the village doctor examines the old man, he notices how naturally the wings fit in with the rest of his body. In fact, the doctor even wonders why everyone else doesn’t have wings as well. The ultimate effect is to suggest that the old man is both natural and supernatural at once, having the wings of a heavenly messenger but all the frailties of an earthly creature. The Spider Woman The spider woman represents the fickleness with which many self-interested people approach their own faith. After hearing of the “angel,” hundreds of villagers flock to Pelayo’s house, motivated partly by faith but also to see him perform miracles—physical evidence that their faith is justified. Not surprisingly, the old man’s reputation wanes when he proves capable of performing only minor “consolation miracles.” Instead, the spectators flock to the spider woman, who tells a heart-wrenching story with a clear, easy-to-digest lesson in morality that contrasts sharply with the obscurity of the old man’s existence and purpose. Although no less strange than the winged old man, the spider woman is easier to understand and even pity. The old man, barely conscious in his filthy chicken coop, can’t match her appeal, even though some suspect that he came from the heavens. García Márquez strongly suggests that the pilgrims’ result-oriented faith isn’t really faith at all. Magical Realism García Márquez’s literary reputation is inseparable from the term magical realism, a phrase that literary critics coined to describe the distinctive blend of fantasy and realism in his and many other Latin American authors’ work. Magical-realist fiction consists of mostly true-to-life narrative punctuated by moments of whimsical, often symbolic, fantasy described in the same matter-of-fact tone. Magical realism has become such an established form in Latin America partly because the style is strongly connected to the folkloric storytelling that’s still popular in rural communities. The genre, therefore, attempts to connect two traditions—the “low” folkloric and the “high” literary—into a seamless whole that embraces the extremes of Latin American culture. As the worldwide popularity of García Márquez’s writing testifies, it is a formula that resonates well with readers around the world. “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings” is one of the most well-known examples of the magical realist style, combining the homely details of Pelayo and Elisenda’s life with fantastic elements such as a flying man and a spider woman to create a tone of equal parts local-color story and fairy tale. From the beginning of the story, García Márquez’s style comes through in his unusual, almost fairy tale–like description of the relentless rain: “The world had been sad since Tuesday.” There is a mingling of the fantastic and ordinary in all the descriptions, including the swarms of crabs that invade Pelayo and Elisenda’s home and the muddy sand of the beach that in the rainy grayness looks “like powdered light.” It is in this strange, highly textured, dreamlike setting that the old winged man appears, a living myth, who is nevertheless covered in lice and dressed in rags. Satire “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings” functions as a satirical piece that mocks both the Catholic Church and human nature in general. García Márquez criticizes the church through Father Gonzaga’s superiors in Rome, who seem to be in no hurry to discover the truth about the bedraggled, so-called angel. Instead, they ask Father Gonzaga to study the old man’s unintelligible dialect to see whether it has any relation to Aramaic, the language of Jesus. They also ask Gonzaga to determine how many times the old man can fit on the head of a pin, another dig at Catholicism referencing an arcane medieval theory once thought to prove God’s omnipotence. Their final conclusion that the old man with wings may in fact be a stranded Norwegian sailor only makes the church sound absurdly literal-minded and out of touch with even the most basic elements of reality. In the end, the church’s wait-and-see tactic pays off when the old man simply flies away—a rib from García Márquez implying that the “wisdom” of the church has never really been needed at all. Such criticisms of the church are only part of García Márquez’s critique of human beings in general, who never seem to understand the greater significance of life. There is a narrowness of vision that afflicts everyone from the wise neighbor woman, with her unthinking know-it-all ways, to the kindly Father Gonzaga, who is desperate for a procedure to follow, to the crowds of onlookers and pilgrims with their selfish concerns. Elisenda too is more focused on keeping her kitchen and living room angel-free than on considering the odd beauty of her unwelcome guest. She, however, seems to have a moment of realization and almost of regret at the end of the story, when she watches the old man disappear from her life forever. Just as the proverbial lost hiker who can’t see the wilderness for the trees, García Márquez suggests that most people live their lives unaware of their significance in the world.