Preface: A Quick Introduction to my family and me

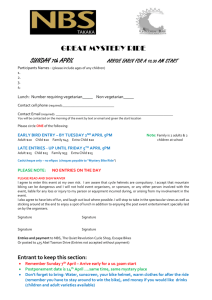

advertisement