A timeline of Clarkson`s life

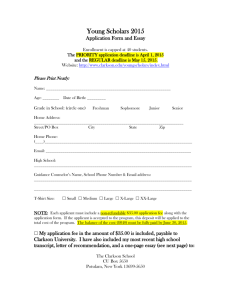

advertisement

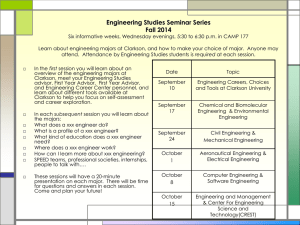

STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE THOMAS CLARKSON AND THE ABOLITION OF THE SLAVE TRADE DOCUMENT 1: How did one man help change the world? The Thomas Clarkson story – The KEY EVENTS SECTION A: THE ESSAY THAT CHANGED A YOUNG MAN’S LIFE 1760 Thomas Clarkson was born in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire on 28th March. His father was the local headmaster. Clarkson was only six when his father died in 1766. Clarkson went to the local grammar school and later Cambridge University (St John’s College). He intended to join the church. Friends describe him as a kind, generous and shy man. Clarkson was over six feet tall and always tended to wear black. 1785 Clarkson entered an essay writing competition at Cambridge University. The subject was: ‘Is it lawful to make slaves of others against their wills?’ The essay was set by Dr Peckard who had been angered by reports of the slave ship Zong. The Case of the Slave Ship Zong In 1783 Collingwood, the captain of the Zong had ordered that over 130 sick slaves be thrown overboard. The slave ship had left Africa in early September. By late November over 60 slaves had died and many others were seriously ill. Collingwood knew that when he reached Jamaica he would not be D.Banham Page 1 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE able to sell the sick slaves and that the ship’s owners would lose money. However, Collingwood thought that if they threw the sick slaves overboard the owners would be able to claim money back from the insurance company. Those slaves that put up a fight were chained before they were thrown overboard. Granville Sharp tried to prosecute the ship’s captain for murder but failed. The owners claimed insurance money for the ‘lost’ slaves, trying to pretend that the ship had run out of water so some of the slaves had to be killed in order to save the crew and the ‘more healthy’ slaves. When the Zong finally arrived in Jamaica on 22 December it still had over 400 gallons of water left. Clarkson, like many people in Britain at the time knew very little about the horrors of the slave trade. He spent the next two months reading up on the subject of slavery. As he read his feelings started to change. It was “It was but one gloomy subject from morning to night. In the daytime I was uneasy. In the night I had little rest. I sometimes never closed my eye-lids for grief.” His research made him realise how evil the slave trade was. He was shocked and deeply affected by what he discovered about the methods of the slavers in capturing or purchasing slaves in Africa and the conditions and treatment of the slaves on the voyage to the British West Indian Colonies. D.Banham Page 2 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE Slave ships from Britain left ports like London, Liverpool and Bristol for West Africa carrying goods. These products were exchanged for captured Africans in a series of timeconsuming negotiations with African slave traders at various points along the coast. This process could take many months. With profit in mind, the captain was always anxious to ensure that only the fittest Africans were boarded, which involved the painful separation of friends and families shown in the image above. After completing his essay Clarkson left Cambridge for London. However, he soon learnt that his essay had won first prize and in the summer of 1785 he D.Banham Page 3 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE was invited back to the university to read it in the Senate House. On his way back to London he could not get the subject of slavery out of his thoughts. Clarkson became increasingly dismayed and angry at the thought that slavery would continue. As he reached Wadesmill in Hertfordshire, Clarkson stopped, sat down and reflected on his life, I sat down disconsolate on the turf by the roadside and held my horse … if the contents of the essay were true, it was time some person should see these calamities to the end. It was here at Wadesmill that Clarkson decided to devote his life to abolishing the slave trade. D.Banham Page 4 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE SECTION B: THE CAMPAIGNING YEARS 1786 During the autumn of 1785 Clarkson added to his essay, hoping to get it published. In January 1786 he bumped into a family friend, Joseph Hancock, who took him to see James Philips, a Quaker bookseller and printer. Philips agreed to publish Clarkson’s essay. In June Clarkson’s 256 page ‘Essay on the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, Particularly the African’ was published. It was written in a very persuasive style and fiercely attacked slavery and the slave trade. The essay was widely read and made Clarkson a well-known figure. It was also through Philips that Clarkson met other people who were already active in their opposition to the slave trade. Clarkson learned of a committee named in 1783 by the London Yearly Meeting for Sufferings to promote total abolition of the slave trade and gradual emancipation. The Quakers had already sent petitions to parliament and placed anti-slavery articles in newspapers. However, their efforts had passed almost unnoticed. Outside of this Quaker group Clarkson also met Reverend James Ramsay, Granville Sharp and other writers who were already involved in campaigning for the end of slavery. Ramsay’s writings on the horrors of West Indian slavery had provoked a great deal of controversy and public interest. Ramsay had lived for 19 years on St Christopher and his ‘essay’, published in 1784, exposed the cruelty of life on the plantations. Granville Sharp had tried to have the captain of the slave ship Zong prosecuted for murder. He had also fought a series of legal battles to prevent West Indian ‘owners’ from taking ‘their’ slaves out of England by force. Clarkson was aware that these different groups needed to be brought together and put pressure on parliament to investigate the slave trade. Clarkson, together with Richard Philips (a cousin of his publisher), worked out the tactics for a united national campaign to ban the slave trade. D.Banham Page 5 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE LONDON Late 1786-Early 1787 Clarkson was also aware of the need to expand his knowledge of the slave trade so that arguments could be put to parliament supported by hard facts. Clarkson’s starting point was the port of London, before moving on to explore the larger slaving centres of Bristol and London. He found ships leaving London containing goods such as cloth, guns, ironware and drink that had been manufactured in Britain. On the African coast these goods would be traded for slaves. On the brutal ‘Middle Passage’ slaves were densely packed onto ships that would carry them to the West Indies. Here they would be sold to the highest bidder at slave auctions. The ships were then loaded with produce from the plantations for the voyage home. The first African trading ship Clarkson boarded was not a slave ship. However, it has a dramatic impact upon Clarkson. The Lively had arrived from Africa with an exotic cargo of ivory, beeswax, palm oil, pepper and beautifully woven and dyed cloth. Clarkson realised that many of the goods had been produced by skilled craftsmen and was horrified to think that these people might be made slaves. Clarkson bought samples of everything and added to this collection over the following years. Clarkson kept these products in a small trunk and used the contents to demonstrate the ingenuity of Africans and the possibilities that existed for a humane trading system. D.Banham Page 6 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE This painting was produced by A E Chalon. On the mantel are busts of William Wilberforce (Left) and Granville Sharp; on the table a map of Africa. At his feet is Clarkson's Box, a collection of the products of Africa. The chest contains samples of African produce and manufacture – woods, ivory, pepper, gum, cinnamon, tobacco, cotton, an African loom and spindle. Clarkson tried to show that African foodstuffs, dye plants and manufactures, such as fine textiles, could replace the trade in slaves, to the benefit of both African and European traders. Clarkson visited African trading ships and collected some of the intricate goods they sold. He kept these in the chest and used them to prove that the Africans were creative, cultured human beings. Clarkson’s aim was to challenge the negative, misinformed view of Africans held by many British people at the time. He also believed that humane trading links could be established that would benefit both sides. Clarkson pictured shiploads of sugar, cotton, indigo, tobacco, oils, waxes and gums, spices and woods, gold and ivory leaving African ports for British markets. When Clarkson first stepped on the deck of a slave ship, the Fly, he saw the dark hold, protected by gratings, where the slaves had been packed. The conditions that the slaves had to endure on ships such as these filled him with such horror, sadness and anger that he quickly left the ship, too upset too continue. 1787 In May the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade was formed. 12 men formed the executive committee. These included Clarkson, James and Richard Phillips and Granville Sharp (who became Chairman of the committee). D.Banham Page 7 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE The society was able to persuade William Wilberforce, the MP for Hull, to be their spokesman in parliament. Wilberforce was wealthy, influential and an excellent public speaker. He was close friends with the Prime Minister, William Pitt. Wilberforce was able to use his contacts to try and set up a parliamentary investigation into the slave trade. Clarkson and Wilberforce agreed to meet often. Clarkson has been portrayed in modern times as a man who ‘worked for’ and ‘took orders’ from the Committee. However, no such commands appear in the official records. It is clear that Clarkson played a crucial role in shaping the direction of the movement. Clarkson dominates much of the business. His writings are treated as the most important that the Committee publish and are the most widely distributed. In their biography of their father (published in 1838), Wilberforce’s sons put forward the view the Wilberforce directed the Committee from the very start and provided its sense of direction. This does not appear to have been the case. Wilberforce never identified himself closely with the Abolition Committee. The goal was the same but Wilberforce and the Committee each made a distinctive contribution. 1787-1794: A SUMMARY Clarkson made a number of important contributions to the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade over the next seven years. (1) RESEARCH Clarkson worked hard to collect as much evidence as possible that would prove how badly slaves were treated. His research was used by Wilberforce in parliament to raise awareness of the horrors of the slave trade. Wilberforce quickly became the voice of the anti-slavery cause in parliament and was able to make it a topic of hot debate. Meanwhile, Clarkson’s travels would take him 35,000 miles around the country and make him one of the best known men in the kingdom. He spent the summer and autumn months touring the slave ports and drumming up support for the anti-slavery cause in towns across the country. The rest of his time was spent in Wisbech or London writing up his findings and keeping in touch with local anti-slavery groups. D.Banham Page 8 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE Clarkson interviewed thousands of sailors and managed to obtain equipment used in the slave trade, such as iron handcuffs, leg shackles, branding irons, thumbscrews and instruments for forcing open slaves’ jaws. Perhaps the most famous illustration of a plan of a slave ship (‘Brookes’) showing the cramped conditions comes from one of his books. Clarkson faced a lot of opposition. The slave traders had friends in high places. Members of the royal family and some bishops were against abolishing the slave trade. Many people were making a great deal of money from the slave trade. Clarkson’s work was also very dangerous. Most of his meetings with informants had to take place secretly in darkness. Slave traders and sailors often threatened Clarkson. In 1787 on a visit to Liverpool he had a lucky escape from a gang of sailors paid to assassinate him. Clarkson was attacked and nearly thrown overboard but managed to escape with his life. When Clarkson investigated the death of a seaman, Peter Green, who was flogged and had his brains beaten out by his captain, Clarkson was told that he was ‘now so hated that he would be torn to pieces’ if he ever tried to bring the case to trial. (2) FINDING WITNESSES Clarkson’s also attempted to try and find witnesses that would appear before parliament. Clarkson often struggled to find people who were willing to give evidence against the slave trade. However, he was very determined and refused to give in. For example, in 1790 he visited 317 ships in London, Portsmouth and Plymouth in three weeks, in search of a sailor who had crucial evidence about the capture of slaves, and about whom he only had a rough description. (3) ORGANISING LOCAL PRESSURE GROUPS Clarkson also aimed to organise local groups that could put pressure on the government to abolish the slave trade. Clarkson worked hard to rally support for his anti-slavery campaign. He organised many petitions and helped local groups raise money to support the cause. Clarkson inspired and educated D.Banham Page 9 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE supporters of the campaign. In Manchester, for example, after he gave a speech at the Collegiate Church in 1787 a petition in favour of banning the slave trade was signed by 11,000 people (this was more than a fifth of the town’s population). Clarkson also encouraged the public to boycott goods such as sugar which had been produced by slaves. It is estimated that during this period 300,000 people boycotted sugar produced in the West Indies. Clarkson managed to gain a great deal of public support for the campaign to stop the slave trade. In 1792, 519 petitions opposing the slave trade were sent to Parliament. 1787: BRISTOL In 1787 Clarkson visited Bristol. He wanted to know about the state of trade with Africa, including the trade in timber and ivory, as well as the slave trade. He also wanted to find out about conditions on the slave ships. Clarkson’s contact was a Quaker named Harry Gandy, who as a youth had sailed on two slaving voyages to Sierra Leone. At first, information was easy enough to come by and Clarkson soon collected a thick catalogue of horrors, involving cruelty to slaves and British seamen. On one occasion he boarded two small ships that were being fitted out to carry slaves from Africa to the West Indies. He measured the space for the 100 slaves and calculated that only three square feet had been allocated for each adult. Clarkson also met two surgeons who had worked on the slave ships. James Arnold told Clarkson of the savage beatings given to slaves. When two victims rebelled one was shot and the other fatally scolded with hot fat. Arnold promised to keep a journal for Clarkson on his next voyage on the ship ‘The Ruby’. Clarkson used this diary as evidence against the slave trade. Alexander Falconbridge had been on four slave ship voyages. For the last two years he had been working as a doctor in Bristol. Falconbridge, along with Harry Gandy, was willing to go to London to testify before parliament. Falconbridge’s ‘An Account of the Slave Trade on the Coast of Africa’ D.Banham Page 10 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE (written essentially by Richard Phillips) was published by the Committee in 1788. It was blunt, factual and proved to be very influential. 1787: LIVERPOOL Leaving Bristol, Clarkson pressed on to Liverpool, stopping at major towns along the way (such as Gloucester, Worcester and Chester) to contact local clergymen, mayors and publishers who might support his campaign. Liverpool’s six miles of docks was the slaving capital of the world. For the first time Clarkson saw the tools of the trade displayed in a shop window and he bought iron handcuffs, leg shackles, a hideous thumb screw and a speculum oris, which was used to wrench open the mouth of any slave who refused to eat. Illustration of handcuffs and leg shackles, bought in a Liverpool shop. From Clarkson’s History of the...Abolition of the African Slave Trade, 1807. D.Banham Page 11 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE Whilst in Liverpool, Clarkson went to see the poet and writer Edward Rushton who had once been an officer on a slave ship. Rushton had been saved from drowning by a slave and had befriended the slaves in return. Rushton described in detail to Clarkson the evils of the trade and agreed to sign his statement. Another valuable source of information was Robert Norris, a retired slave captain and now a leading merchant. He gave Clarkson the manuscript of a voyage to Africa which contained many examples of cruelty in the trade. Clarkson was joined by Falconbridge in Liverpool but they found few people willing to testify. Many people were scared to provide evidence because they feared that their houses would be pulled down in revenge by supporters of the slave trade. It became increasingly dangerous for Clarkson to stay in Liverpool. When Clarkson investigated the death of a seaman, Peter Green, he was told that he was ‘now so hated that he would be torn to pieces and his lodgings burned down’ if he ever tried to bring the case to trial. Green, serving as a steward on a slave ship off the African coast, had been accused of assault by a black woman interpreter who belonged to the ship’s owners. Green had refused to give her the keys to the ship’s wine store. The captain flogged Green for two and a half hours, ripping his back open with the cat-of-nine tails and beating his brains out with a knotted rope. Green was still alive when he was cut down but was then shackled and lowered into a small boat alongside the ship. He was found dead the next morning. This case illustrated how British seamen as well as the African slaves were victims of the slave trade. When Clarkson checked the records he found that Green was one of 16 seamen who died on the slave ship’s voyage. Using records collected in London and Liverpool, Clarkson estimated that one in five British seamen who served on slave ships died on their voyage. This statistic shocked the public and became one of the abolitionist’s most successful arguments against the trade. Clarkson also had a lucky escape from a gang of sailors that seem to have been paid to assassinate him. Clarkson was alone on a pierhead when he was attacked by eight or nine men who attempted to shove him towards the end of the pier. Clarkson believed that the gang was determined to throw him into the sea and make it look like an accident. Fortunately he was able to D.Banham Page 12 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE push one of the gang to the ground and despite being hit by the others he was able to break through and escape. 1787: MANCHESTER After Liverpool, Clarkson rode to Manchester. They invited Clarkson to speak at the Collegiate Church. Clarkson delivered a powerful and moving speech. He argued that Christianity preaches that ‘we should not do that to others, which we would be unwilling to have done unto ourselves’ yet the African slave ‘drinks at the cup of sorrow and drinks it at our hands’. Clarkson highlighted how thousands of Africans each year were being torn from their homeland, family and friends only to be forced into the degradation of being the ‘possession of a man to whom he never gave offence’. Clarkson gave specific examples from his own research into the cruel way in which slaves were treated. How inconsistent, he declared, to pray for God’s mercy on ourselves ‘who have no mercy upon others’. Clarkson ended by calling on the congregation to join the cause of abolition so that ‘the stain of the blood of Africa is not upon us’. When Manchester’s petition was sent to parliament it had been signed by nearly 11,000 people, more than a fifth of the town’s population. 1787: Journey’s End By the time Clarkson returned to London he had been away for more that five months. He had inspired many people around the country to support the abolition cause. He had also collected the names of more than 20,000 seamen in the slave trade and he knew what had become of each one. By the end of 1787 the abolition movement had grown considerably and attracted support in almost every county. A slave medallion from the Wedgwood factory became the movement’s most powerful symbol. D.Banham Page 13 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE William Hackwood designed this famous medallion for the campaign. It was produced in jasperware by one of Britain’s leading industrialists, Josiah Wedgwood, who was a keen supporter of the campaign to end slavery. The medallion portrayed a kneeling African in chains framed with the words ‘Am I not a man and a brother? This motto became the rallying cry for the campaign. The image was distributed in thousands. Clarkson alone gave out 500 on his travels. The abolitionists also found that fashion promoted justice. The image was inlaid in gold on snuff-boxes and set into bracelets and hairpins. Perhaps parallels can be drawn with the wrist bands of 2005! 1788 In 1788 Clarkson published an ‘Essay on the Impolicy of the African Slave Trade’ in which he argued that slavery was immoral and not in the national interest. He also highlighted the extraordinarily high death rates amongst seamen on the slave ships and lucrative alternative for merchants trading to Africa. By now, having already published two major works on the topic, Clarkson was seen as the country’s main expert on slavery. Meanwhile, Wilberforce was able to raise the issue of slavery with parliament; the order was given that the first slave-trade inquiry should be established. Some members of parliament responded enthusiastically. 2 MPs D.Banham Page 14 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE (William Morton Pitt and James Martin) joined the Committee. The abolitionists launched a propaganda campaign to try and raise support for the cause around the country. Clarkson’s work was reissued and Falconbridge’s account of his four sailing voyages was published. In addition, the Reverend John Newton wrote Thoughts Upon the African Slave Trade, which was filled with powerful images of slaves packed as close as ‘books upon a shelf’, at the mercy of the drunken crews. During May the issue of slavery and in particular conditions on the slave ship was a topic of hot debate. On 9 May, William Pitt described the slave trade as the most important subject ever raised in the House of Commons. William Dolben, MP for Oxford University, who had inspected a slave ship in the Thames, described the ‘crying evil’ of the Middle Passage, the horrors of slaves chained hand and foot, stricken with illness. He wanted to introduce a law that would improve conditions on the slave ships. During the inquiry that followed the House of Commons heard evidence from both sides for the next two weeks. A witness for the slave trade described how ‘delightful’ the slave ships were, Robert Norris stated ‘[The slaves] had sufficient room, sufficient air, and sufficient provisions. When upon deck, they made merry and amused themselves with dancing… In short, the voyage from Africa to the West Indies was one of the happiest periods of a Negro’s life.’ The evidence provided by Clarkson and a detailed report Pitt had established to look into conditions on Liverpool slave ships told a very different story. Each slave had a five and a half foot by sixteen inch space to lie in, spent up to 16 hours of every 24 chained to his neighbour and after a small meal of yams and beans was forced to jump in his irons for exercise. A law (The Dolben Act) was subsequently passed which fixed the number of slaves in proportion to the ship’s size. The abolitionists were hopeful that this was the first step towards banning the slave trade and that they would have achieved this aim by the end of 1789. In the second half of 1788, Clarkson set about collecting more witnesses and evidence that he hoped would win the argument in parliament for abolition. D.Banham Page 15 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE He set out on another tour, covering 1600 miles in two months. At Plymouth he uncovered a key piece of evidence, the plan and section of a loaded slave ship. Clarkson reworked in London, applying the idea to the Brookes (a slave ship from Liverpool). The plan shows how the enslaved Africans would have been positioned inside the hull of the ship. In 1788, Parliament tried to restrict the number of captured Africans that a ship could carry across the Atlantic. This famous diagram shows the slave ship Brookes carrying 454 Africans, which was its regulated number. This image was used to expose the appallingly cramped conditions below deck. In fact, the Brookes had carried as many as 609 Africans on earlier voyages. Despite the government’s intervention in the trade, the new restrictions were not actively enforced. This shocking diagram was published in April 1789 and widely distributed. It was a powerful visual representation of the cramped conditions on the slave ships that still existed despite the new law. Wadstrom’s research (published in 1794) also made this point. He calculated that on a slave ship a man was given a space of 6 feet by 1 foot 4 inches; a woman 5 feet by 1 foot 4 inches and girls 4 feet 6 inches by 1 foot. 1789 In May, Wilberforce begun the debate on the abolition of the slave trade. His speech lasted for three and a half hours. However, supporters of the slave trade managed to delay by asking for a new inquiry and the question was put over until 1790. D.Banham Page 16 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE At Wilberforce’s suggestion, Clarkson went to France for six months, during the start of the French Revolution, to encourage the revolutionaries to abolish the French slave trade. The French trade at this time was at an all time peak. Clarkson was seen as the best-informed person on the subject and was well known in France through his writings and contacts with men in the French abolition movement. Whilst in France, Clarkson distributed 1000 copies of the famous Brookes slave ship plan and his 1788 essay (Impolicy of the African Slave Trade’). Clarkson had powerful enemies working against him in France and he suffered from a lot of abuse. He received a threat that he would be stabbed to death and rumours were begun that he was a British government spy. Although France did not abandon the trade, Clarkson’s efforts were not forgotten. Later in 1792 Clarkson was made an Honorary Citizen of France. During his stay in France Clarkson met Vincent Oge from Saint Dominque (now Haiti) who was campaigning for the abolition of slavery on the French colony. Oge knew and admired Clarkson’s work and visited him at his hotel. Three months later Oge returned home and led an unsuccessful uprising. The colonial authorities broke him on the wheel and cut off his head. This marked the start of a bloody war in Haiti. 1790 Clarkson returned home to England in order to prepare evidence for the new House of Commons inquiry. He discovered that nine of the sixteen witnesses he had intended to produce had disappeared. Clarkson spent three weeks on the road trying to find possible replacements. A search for one witness shows how determined Clarkson was in his efforts to support the cause. Clarkson wanted to find out how slavers obtained slaves in Africa. He had heard that in the Calabar and Bonny Rivers, when slave ships lay offshore, fleets of well-armed canoes manned by Africans swarmed inland and returned with slaves to fill the ships. The slave traders had claimed that they purchased the slaves at African fairs or markets. Clarkson set off in search of a sailor who had been on one such slaving expedition. He rode to Woolwich, Chatham, Sheerness, Portsmouth and finally Plymouth, boarding 317 ships and interviewing their crews before he finally found his man (Isaac Parker). Parker had seen villages attacked and people seized at gunpoint. D.Banham Page 17 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE Clarkson also undertook a tour of the North that would take him 7000 miles and last four months. He ended up finding another 20 witnesses for the parliamentary enquiry which now dragged on into 1791. 1791 In April, William Wilberforce introduced his first Bill to abolish the slave trade. However, despite the mountain of evidence that Clarkson had collected and a brilliant speech by Wilberforce in parliament it was heavily defeated by 163 votes to 88 votes. Wilberforce and Clarkson refused to be put off by this setback and their fight against slavery continued. Clarkson again traveled around the country in order to keep the anti-slavery campaign going. This time he traveled throughout England, Wales and Scotland, covering 6000 miles. Wilberforce was now convinced that only massive public support could persuade parliament to abolish the slave trade. Clarkson encouraged new committees to be set up in places such as Nottingham, Newcastle and Glasgow. He helped to organize new petitions and keep the issue in the local press. Clarkson also encouraged people to join the boycott of West-Indian slave grown sugar. This voluntary ban on sugar had been inspired by pamphlets produced by William Crafton of Tewkesbury and William Fox of London. Clarkson calculated that around the country 300,000 people were now refusing West Indian sugar. 1792 During 1792 a total of 519 petitions from all over the country poured into parliament calling for the abolition of the slave trade. This was the height of the public campaign. In April, parliament once again debated abolishing the slave trade. Pitt gave a brilliant speech supporting Wilberforce, said to be one of the greatest ever heard in parliament. However, Henry Dundas proposed an amendment to insert the word ‘gradually’ into Wilberforce’s motion to abolish the trade. The House of Commons agreed and by 230 votes to 85 pledged itself to ‘gradually abolish’ the British slave trade. 1796 was fixed as the year when the trade would end but it was never implemented. By 1793 Britain was at war with France and both public and parliamentary interest in the slave trade fell drastically. 1793 By August Clarkson was beginning to suffer from ill health as a result of his work. He was physically and mentally exhausted. Constant traveling, often by horseback and sitting up writing until two or three in the morning had left him seriously ill. As he himself recorded D.Banham Page 18 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE I am often suddenly seized with giddiness and cramps. I feel an unpleasant ringing in my ears, my hands frequently tremble. Cold sweats suddenly come upon me… I find myself weak, easily fatigued, and out of breath … I feel myself almost daily getting worse and worse. Clarkson had given up what would have been a comfortable career in the church (earning approximately £2000 a year) to work for the abolition of slavery and was by now also very short of money. He had often paid out of his own pockets to send coach-loads of sailors to London to give evidence to parliament. D.Banham Page 19 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE SECTION C: A BRIEF RETIREMENT – THEN SUCCESS AT LAST 1796 In January, Clarkson married Catherine Buck from Bury St Edmunds. They moved to the Lake District buying a 35 acre farm and building a cottage at Eusemere Hill, overlooking Ullswater. In October their only child, Tom, was born. The Clarkson’s became good friends with the Lake poets (Wordsworth, Coleridge and Southey). Clarkson gave up work for 8 years. In March Wilberforce introduced a bill which would fix the end of the slave trade at 1 March 1797. However, it failed on its third reading by just four votes. The anti-slavery movement struggled to make an impact without Clarkson. Even the Committee of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade held no meetings between 1797 and 1804. However, Wilberforce did manage to keep the subject alive in the House of Commons. 1803. Clarkson and his family moved to Bury St Edmunds. Here they lived in a house belonging to Catherine’s father in St Mary’s Square. 1804 Clarkson’s ‘retirement’ from the campaign to abolish the salve trade ended in 1804. In May Clarkson became active in the anti-slavery campaign again. The committee was expanded from 12 to 40 but still included original members such as Clarkson, Sharp and Phillips. For the next three years they worked hard to gain support for the cause, concentrating most of their efforts on parliament. 1805 Clarkson undertook another tour of England. His aim was to gather together witnesses and build support for the anti-slavery movement. He found that there was a lot of work to be done with young people, many of whom knew little about the cause because few books or pamphlets had been published in recent years. Clarkson was able to reactivate many of the local committees. 1806 In 1806 the new government of Grenville (with Fox as foreign secretary) managed to push through a law banning the slave trade to captured colonies. Clarkson and his family moved to Bury St Edmunds, living in house in St Mary’s square at the end of Westgate Street for the next 10 years. Their D.Banham Page 20 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE son, Tom, was enrolled in the local King Edward VI grammar school in Northgate Street. 1807 The slave trade was finally abolished in the British Empire. Lord Grenville masterminded the victory. He started where the move could expect most opposition, in the House of Lords, introducing a bill to stop the trade to the British colonies on the grounds of justice, humanity and sound policy. Due to careful planning and canvassing of support the bill passed the Lords by 100 votes to 34. In the Commons, when the debate took place, MPs actually competed to be heard. The Abolition of the Slave Trade Act was passed by 283 votes to 16. This was a sign of the careful work carried out in parliament by Grenville and the widespread support that Clarkson and other anti-slavery campaigners had built up through their campaigns and tours around the country. The new law stated that any British captain caught with slaves on board would be fined £10 for every slave on the ship. This was a significant achievement for the anti-slavery movement but the law did not go far enough. It did not outlaw slavery completely or make any arrangements for slaves to be set free. Some slave-ships that were in danger of being captured threw slaves overboard before reaching British controlled waters. Clarkson also realized that the slave trade was likely to continue so long as there was a market for slaves. At his suggestion a committee was set up to keep a watch on British and foreign ports. In addition, along with Wilberforce Clarkson served on another committee to collect data on slavery in the British colonies. D.Banham Page 21 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE SECTION D: ON THE INTERNATIONAL STAGE 1807-c1820: A summary Between the victory over the British slave trade in 1807 and the start of the antislavery campaign in the 1820s Clarkson’s role changed. He became more and more involved on the international stage and together with other abolitionists fought for an internationally enforced ban on the slave trade in Europe. Countries such as France, Portugal and Spain still traded in slaves. He also established links with the King of Haiti. Clarkson’s involvement on the international stage is remarkable, given that he was a private citizen, with little money and only limited access to the government. 1808 Clarkson published his history of the abolition movement. The only contemporary published record of the origin and growth of the British antislave-trade movement. During his time in Bury St Edmunds, Clarkson supported other important causes and was active in local issues. He argued that the use of the death penalty should be reduced (at this time more than 200 offences carried the death penalty – from stealing property worth five shillings to forgery and murder) and supported pacifism. The first meeting of the Society for the Promotion of Permanent and Universal Peace took place in 1814, chaired by Clarkson’s brother, John. 1814 The war with France ended when Louis XVIII came to the throne in France and Napoleon was exiled to Elba. Abolitionists such as Clarkson were disappointed when, under the conditions of the Treaty of Paris, France was allowed to continue the slave trade for five years. The abolitionists had urged the British government to insist that France abolished the slave trade in return for getting their colonies back. Wilberforce told the House of Commons that the actions of the government meant a ‘death warrant’ for thousands. In protest at the actions of the government a huge public rally was held at Freemasons’ Hall in June, whilst the Russian Emperor and King of Prussia (allies of Britain in the war against France) were in London. Clarkson helped to organize local groups who encouraged members of the public to express their disappointment with the government’s failure to put a block on the French slave trade. A total of 861 petitions, signed by 755,000 people were sent to parliament. Clarkson then traveled to Paris. By circulating his works D.Banham Page 22 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE and talking to prominent people, Clarkson hoped to encourage the French government to end the slave trade sooner than the treaty provided for. 1815 Clarkson returned to Paris in September, 1815. His aim was to speak to the Tsar Alexander I. Russia had no African slave trade and Alexander was a known supporter of abolition. Clarkson hoped that the Russian Tsar could persuade other allied leaders to support the abolition of the slave trade across Europe. Clarkson met Alexander and learnt that he had read Clarkson’s books. The Russian Tsar invited Clarkson to write to him with suggestion on how the slave trade could be ended. In 1815 Clarkson also began correspondence with Henry Christophe, the black ruler of independent Haiti. (After the failure of Oge’s revolt and a series of race-wars the blacks in Haiti had won their freedom. Christophe ha d fought with Toussaint l’Ouverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines. Toussaint died in a French prison; Dessalines was murdered in 1804. Christophe as commander of the army took control of the north of Haiti, while Alexander Petion, his rival, became president of a southern republic. In 1811 Christophe made himself Henry I, King of Haiti. His country lived under the threat that the French would try and reclaim it.) Henry hoped for trade and international recognition, which had been withheld. He turned to Wilberforce and Clarkson for support. Clarkson became Haiti’s European advisor. Clarkson traveled to Paris in 1819 and 1820 to gather information for Henry. Henry shot himself after his army rebelled against him in October, 1820. His two sons were bayoneted but the Queen and her two daughters were spared. For a few months (1821-22) Madame Marie-Louise and her two daughters lived with the Clarkson’s at Playford Hall, near Ipswich. 1816 Clarkson moved to Playford Hall and lived there until his death in 1846. His friend from University, the Earl of Bristol, owned the hall and let this and its 340 acre farm to Clarkson. Catherine looked after the local school whilst Clarkson became a ‘gentleman farmer’. D.Banham Page 23 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE Playford Hall near Ipswich 1818 Clarkson attended the congress of European powers (Austria, Britain, France’ Prussia and Russia) at Aix-la-Chapelle. He hoped to put forward the King of Haiti’s case and press once again for an internationally enforced ban on the slave trade. Whilst at Aix-la-Chapelle, Clarkson again met with the Emperor of Russia. However, their efforts were unsuccessful, other leaders would not interfere with trade. 1822 At the Congress of Verona in 1822, Wilberforce and Clarkson once again appealed to the European powers to ban the slave trade but their efforts failed. D.Banham Page 24 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE SECTION E: THE ANTI-SLAVERY CAMPAIGN 1823 The Society for Mitigating and Gradually Abolishing the State of Slavery throughout the British Dominions was formed. Younger men led the campaign but Wilberforce and Clarkson gave the movement valuable continuity. Tow years later Wilberforce’s role in the House of Commons was replaced by Thomas Fowell Buxton. Clarkson produced his first pamphlet on the abolition of slavery and gave advice to the Anti-slavery Committee on how to pursue their campaign. Clarkson, aged 63, also undertook another national tour, on order to resurrect the old abolition network of local pressure groups and to start up new ones. Clarkson traveled 10,000 miles in two tours lasting eight and five months. By the summer of 1824, 777 petitions had been sent to parliament. 1824 The Anti-slavery Society held its first public meeting in Freemasons’ Hall in June. Local branches were set up and Clarkson became chairman of the Ipswich branch committee. By 1830 the Anti-slavery society had moved away from gradualism and set itself the goal of immediate emancipation. 1830 Clarkson opened a massive Anti-Slavery Convention in London. Wilberforce was invited to chair this conference of 2000 delegates. The Anti-slavery movement was growing in strength. Lecturers had been employed for the first time to hold public meetings which exposed the horrors of slavery. The number of local branches shot up to 1300 and between October 1830 and April 1831, 5484 petitions were sent to parliament. The antislavery campaign could not be ignored. 1833 The Slavery Abolition Act was passed. Sadly Clarkson’s great friend William Wilberforce died one month before the act was passed. The new law meant that from 1st August 1834 all slaves in the British Empire were given their freedom. Some 800,000 people were no longer slaves. However, the new Act had two controversial clauses. Firstly, £20,000,000 compensation was paid to the slave owners (the amount today would be about £1220 million). Secondly, slaves had to work as ‘apprentices’ until at least 1838, for ‘domestic’ slaves, and 1840 for slaves who worked in the ‘fields’. Only then did they become truly ‘free’. D.Banham Page 25 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE As apprentices slaves and had to work a forty-hour week for six years for their former masters, for no pay. This was still effectively a form of slavery under a different name. Only children under six were given true freedom. This was a sign that the slave-owners still had some political control. In the winter of 1836 Joseph Sturge (a prominent figure in the antislavery movement) sailed to the West Indies and saw that apprenticeships were not improving life for supposedly free blacks. He published his findings in 1837. In 1838 a petitions was presented to parliament protesting about the apprenticeship system signed by 449,000 people. Parliament finally ended the apprenticeship system on 1 August 1838. D.Banham Page 26 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE SECTION F: THE FINAL YEARS By the early 1830s Clarkson’s was once again suffering from health problems. He was almost blind from cataracts and was ordered to slow down by his doctors. However, an operation allowed him to read and write again. During the late 1830s and early 40s Clarkson became involved in the American antislavery movement. In 1833 William Lloyd Garrison, who in 1832 had founded the New England Anti-Slavery Society (which demanded immediate abolition of slavery), visited Clarkson at Playford. 1837 Clarkson’s only child (Tom) is killed in a fatal accident, aged 40. 1838 Wilberforce’s sons publish a biography of their father. It downplays Clarkson’s contribution to the abolition of slavery. Clarkson is forced to defend his reputation. 1839 Clarkson contribution to the cause is honoured by receiving the freedom of the City of London. 1840 By 1840 the British Anti-Slavery had set its sights on abolishing slavery throughout the world. In June they set up a general convention in London. Clarkson was voted President of the convention and accepted a standing tribute form 5000 delegates and observers from Britain, the United States, Canada, France, the West Indies, Switzerland and Spain. Clarkson was treated as a major celebrity and there were many requests for his autograph. By this point Clarkson was the only surviving member of the 1878 committee that had been established to abolish the slave trade. In his speech he attacked the American cotton planters who kept more than 2,000,000 slaves in ‘the most cruel bondage’ and encouraged members of the convention to ‘Take courage, be not dismayed, go, persevere to the last’ until slavery was removed form the world’. 1846 At 4 ‘o’ clock in the morning of 26 September Thomas Clarkson died at Playford Hall aged 86. He was buried at the local church (St Mary’s, Playford). His funeral was very simple and only attended by family and close friends. The route was lined with villagers who joined the procession and filled the church to overflowing. On his death, the poet Coleridge said of him ‘He, if ever human being did it, listened exclusively to his conscience and obeyed its voice.’ D.Banham Page 27 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE DOCUMENT 2: How is Thomas Clarkson remembered? A FORGOTTEN HERO ? Thomas Clarkson was one of the founders of the movement to abolish the slave trade and a driving force in one of the most important protest movements in British history. In 1780 Britain was the greatest slave-trader in the world yet Clarkson risked his own life to try and stop the horrific slave trade. When he started his crusade most people in Britain saw slavery as a natural part of the economy, a ‘necessary evil’ and as old as history. By the time of his death it had come to be seen as a crime. The slave trade was also extremely profitable. There was no shortage of investors. It has been calculated that some voyages made 20-50% profit. In a study of the Liverpool slave trade David Richardson calculated that the profits in 74 voyages averaged over 10%. In his own lifetime he was praised for his courage and heroism. In 1839 Clarkson was given the freedom of the city of London. Clarkson was friends with the famous people of the age – Josiah Wedgewood (the creator of fine china) and poets such as Wordsworth and Colerdige. He also moved in high circles, once meeting with the Russian Emperor in Paris. In 1853, Harriet Beecher Stowe (the American author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin) traveled all the way to Playford to visit Clarkson’s grave. Her book told the story of a slave and helped to change attitudes in America (where slavery still existed). However, today Clarkson’s story seems to have been forgotten. Is he in danger of becoming a footnote in history? In their day Wilberforce and Clarkson were recognized as equals but 200 years on the story is very different. Only, Wilberforce, who fought for the cause so hard in parliament, could be said to be a household name. Yet it was Clarkson who planned the tactics and was able to create massive public support for the campaign. Clarkson believed in the power of educated people. He traveled the country investigating every aspect of the slave trade in detail and communicating his findings to the general public through pamphlets and public meetings. Clarkson helped to form and organise anti-slavery groups in towns throughout the country and has been described by Ellen Gibson Wilson D.Banham Page 28 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE (1989) as ‘the architect’ of the ‘first national campaign for human rights that Britain had known’. Hundreds of people should share the credit for the successful campaign to end the slave trade but in the eyes of people at the time it was Clarkson who was the ‘mastermind’, ‘the link’ that held the campaign together. He was the man who devoted his whole life to the cause and it was Clarkson who was known to people living at the time as the ‘originator’ of the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Clarkson gave his life to the service of people her never met in lands he never saw. He helped to change the way his generation looked at the world, teaching that slavery was a crime. Despite this massive contribution to human rights only two biographies of Clarkson appear to have been published during the 20th century. His role in the campaign to abolish the slave trade has been obscured. Why have so many historians overlooked the role he played in stopping slavery? One problem is that Clarkson never dreamed that anyone would ever write his life-story and as a result threw out most of his papers. The publication of a popular biography of Wilberforce by his sons (Robert and Samuel) in 1838 also had a damaging effect. In the biography, Clarkson is not even mentioned as a member of the Committee and his wider role is largely ignored. The brothers also refused to mention the mutual respect and admiration that Clarkson and Wilberforce had for each other. Clarkson and Wilberforce were a partnership. Both played crucial roles in the campaign to abolish the slave trade. As Clarkson himself wrote What could Mr. Wilberforce have done in parliament if I had not collected that great body of evidence … And what could the committee have done without the parliamentary aid of Mr. Wilberforce? In 1844 Clarkson received an apology from Robert and Samuel Wilberforce, by way of a letter (no public apology was ever made) for the way that they had portrayed him in their book. We were in the wrong in the manner in which we treated you in the Memoir of our father. We are conscious that too jealous a regard for what we thought our Father’s fame, led us to entertain an ungrounded prejudice against you and this led us into a tone of writing which we now acknowledge was practically unjust. D.Banham Page 29 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE The Wilberforce biography has had a powerful influence on later historians. Unlike Clarkson’s account of the abolition movement it is readily available and contains a great deal of source material. It has been treated as an authoritative source and has not always been read with the caution it deserves. Many historians have therefore followed the line taken by Robert and Samuel Wilberforce. Frank Klinberg in his book Anti-Slavery Movement in England (1926) describes Wilberforce as ‘chief adviser’ and says that Clarkson was a ‘field agent’ ‘directed by’ the Committee. In Britain in the Nineteenth Century (1967) George Trvelyan describes the ‘systematic propaganda begun by Sharp and Wilberforce’, thus overlooking Clarkson’s crucial role. It appears that the Wilberforce’s biography, motivated by a desire to tell the story of abolition with their father in the lead role helped to create a myth. Wilberforce took centre stage whilst Clarkson was demoted to the wings. Statements made by 20th century historians are in stark contrast to comments made by contemporaries of Clarkson. Wordsworth published a sonnet, praising Clarkson’s role in the movement to abolish slavery. In 1837 a book by Charles Lamb paid tribute to Clarkson as ‘the true annihilator of the slave trade’ and at the world’s first antislavery convention in June 1840, Clarkson was hailed as the ‘originator’ of the movement. D.Banham Page 30 3/3/2016 How is Clarkson remembered today? STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE Wisbech is one of the few places where Clarkson is still remembered. There is an impressive memorial in town centre, between the Crescent and the Town Bridge. This memorial was erected in 1881 at a cost of £2000. In Bury St Edmunds there is a plaque on the house where Clarkson lived in St Mary’s Square. In Ipswich a street is named after Clarkson and his portrait hangs in the Mayor’s parlour at the Town Hall. However, there is no statue, even though Clarkson lived nearly half is life so close to the town. Clarkson is buried at Playford church, near Ipswich. In the churchyard, on the left of the entrance door, is a granite obelisk, raised to the memory of Thomas Clarkson. The obelisk was erected in 1857 by ‘a few surviving friends’ of Clarkson. There is also a commemorative obelisk on what is now the A10 at Wadesmill in Hertfordshire, where Clarkson made up his mind to try and end the horrors of slavery. In 1996, £20,000 was raised to have a memorial plaque erected in memory of Thomas Clarkson at31 Westminster Abbey in London. D.Banham Page 3/3/2016 STACS THOMAS CLARKSON TIMELINE D.Banham Page 32 3/3/2016