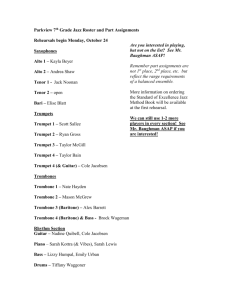

Saint-Saëns : Cavatine

advertisement

Saint-Saëns : Cavatine Written in 1915, the Cavatine, by French composer Camille SaintSaëns is one of the most attractive works in the trombone repertory and celebrates a rapturous late flowering of the ‘Romantic style’. It has figured on examination syllabi and as an audition test ever since its use in a competition at the Paris Conservatoire in 1922 (the year after the composer’s death) and continues to represent both a technical and musical challenge to performers. The trombone has always been very popular in France and throughout the latter part of the nineteenth century was widely accepted as an expressive and distinctive solo instrument. It’s popularity continued into the twentieth century prompting the Paris Conservatoire to establish a tradition of inviting respected composition Professors to provide substantial musical works for use in competitions and examinations. Trombonists are probably aware of other such pieces by Bozza, Büsser, Casterade, Guilmant and Ropartz (to mention just a few) who contributed to the instrument’s repertoire through these commissions. Born in Paris in 1835, Saint-Saëns showed an early talent at the keyboard. His efforts at the piano attracted the attention of many of the greatest musicians of this era including Berlioz, Rossini, Gounod but especially the ultimate master of the keyboard, Franz Liszt, who was particularly impressed by the ability of the young Saint-Saëns to perform any of Beethoven’s 32 Piano Sonatas from memory. Throughout his life success as a composer was supplemented by teaching composition and serving as organist in many of the French capital’s most famous Churches resulting in a wide range of both sacred and secular works. Written when the composer was 80, the Cavatine clearly shows influences of earlier popular compositions, the slow middle section recalling ‘The Swan’ (Carnival of the Animals) and the ecclesiastic flavour of the Adagio (Organ Symphony) where the trombone is also featured as a solo instrument within the orchestral texture. The Cavatine opens with a dramatic chordal statement from the piano introducing the soloist in an arpeggio figure, spanning the interval of a 13th, from low to high register and instantly reveals the ability of the trombonist to produce a refined and consistent tone throughout the range. This can be achieved technically by emphasising the role of ‘air-speed’ in achieving higher notes and economising on the tightening of muscles in the embouchure. If the lip is allowed to become too tense the sound quality of the F in bar 5 will suffer. Try to establish a full round tone on the very first note that with the help of abdominal and diaphragm muscles will allow you to increase the ‘air-speed’ and float easily up the arpeggio. These significant crotchets establish the musical intentions of the performer right away and if played too short rather detract from the nobility of the theme. I have always felt that this rather ‘pompous’ opening phrase is reminiscent of a Victorian drawing room ballade; entertaining, yet a touch melodramatic. In bars 6 and 7 it is useful to recognize where the emphasis is placed on alternate beats thus creating the feeling of three bars of two within the two bars of three! This device, known as a ‘hemiola’, derives from Renaissance times and serves to propel the phrase forward with a kind of energy and bravado. A further compositional device appears from bar 10 where a pair of two bar sequences, assist the musical line and allow the performer to really ‘act out the drama’. One must also assess the intended musical result when choosing the kind of articulation for quaver passages. Again a ‘staccato attack’ may enhance definition but rather detract from elegance and refinement. A combination of a softer ‘da-da’ production with fast and accurate slide action will produce a more flowing and musical result. The serious trombonist is faced with decisions regarding alternate positions on a regular basis and I have tried to annotate a few recommendations throughout the accompanying extracts, which generally follow two rules. The first is obvious proximity of positions but the second is to try to find a circular pattern that allows fluidity and ease of movement of the slide, the trombone’s rather awkward appendage! Fig 1. With so many players choosing instruments with an F valve it is easy to try and solve all ‘shift’ problems by virtually disregarding 6th and 7th position. However, in my experience clarity is frequently enhanced by the extra effort and in any case the added co-ordination required to press the valve down at the right moment in a fast passage can often be compromised when under pressure in a performance. For this reason I would recommend that the low C near the beginning of the rising scale passage in bar 21 is taken in 6th position. Be careful also to resist the tendency to get louder before actually marked in bar 27. As the human ear favours the higher frequencies, be subtle, don’t get too loud too soon and take advantage of this fact in conserving air for the rest of the phrase. Fig. 2 The two descending motifs in bars 48 and 50 can easily turn into an approximate tasteless glissando so be careful to employ neat slurring and to show clarity with refinement. Mastering ‘legato’ is one of the more problematic areas of technique on the trombone. One must appreciate that to play smoothly between two notes the air must remain constant, however, moving on the same harmonic and crossing harmonics requires different solutions. To avoid the ‘dreaded’ glissando or ‘smear’ the slide must remain in the position for as long a possible and move to the next one coinciding exactly with a soft tongue, which briefly ‘interrupts’ the air column but doesn’t stop it. The ‘click’ experienced when gliding across harmonics should as far as possible match up to this, creating a pleasing unity. The middle section of Cavatine, marked Andantino reveals the quality of a performer’s ‘legato style’ and will also challenge breath control (note recommended breath) and intonation (note slight flattening on D# in bar 76). The trombone is hard enough to play in tune with its ‘sliding pitch’ but one must also further pay attention to notes that require adjustment to reflect their position in the harmonic series and in respect of equal temperament (more about ‘micro-tuning’ in next article). Oddly, no actual dynamic is requested in the original version, just the word ‘dolce’, therefore, I recommend a subtle volume and a tempo that will allow the music to flow with a hint of ‘rubato’ and perhaps even ‘vibrato’. These are also ‘thorny subjects’ but in my opinion quite easy to assimilate. The definition of ‘rubato’ is ‘to rob’, therefore, like every pleasant law abiding citizen if ones takes away, then one gives back. Check your ‘rubato’ is not all take! Vibrato is nothing more than an additional colour you carry in your musical tool-bag, one that can be used at different speeds and amplitudes to express your emotions provoked by musical line and harmony (emotive subjects that will be examined at greater length in subsequent issues). Fig. 3 The passage from bar 88-111 is peppered with subtleties, a few of which I have indicated on the fourth extract. Choosing a breathing pattern that is technically and musically satisfying can often produce a variety of solutions and indeed comparison between recordings in the passage bar 90-111 will confirm this. I hope you will find my hints useful guidance when formulating your own interpretation. Fig. 4 The printed music is available in a number of editions though the actual notes remain the same in trombone and piano parts. The one published by Durand is the original and American editions by Master Music and Elkan-Vogel are simply reprints. Editions by Brass Wind and Marc Reift come with treble clef parts, the former with interesting editorial modifications by former BBC Symphony Principal Trombone, Chris Mowat, the latter by John Mortimer but also with an additional version for brass band accompaniment beautifully arranged by James Gourlay. Arrangements for band of piano accompaniments are not always successful but this one intelligently demonstrates knowledge and respect of Saint-Saën’s fine orchestration skills and deserves more frequent performance. For such a popular piece there are strangely not as many available recordings as one might expect, however, the ones listed below demonstrate a range of contrasts, which are well worthy of comparison. Recordings : With Piano : Ron Barron (former Principal Boston Symphony) Le Trombone Francais Boston Brass Series Andy Berryman (former Principal Halle Orchestra) Recital for Trombone Doyen Ian Bousfield (former Principal Vienna Philharmonic) 2 Versions : EMI 1997 & Camerata 2007 Christian Lindberg The Romantic Trombone BIS With Brass Band : Brett Baker Bone Idyll Chandos