Bibliografia

advertisement

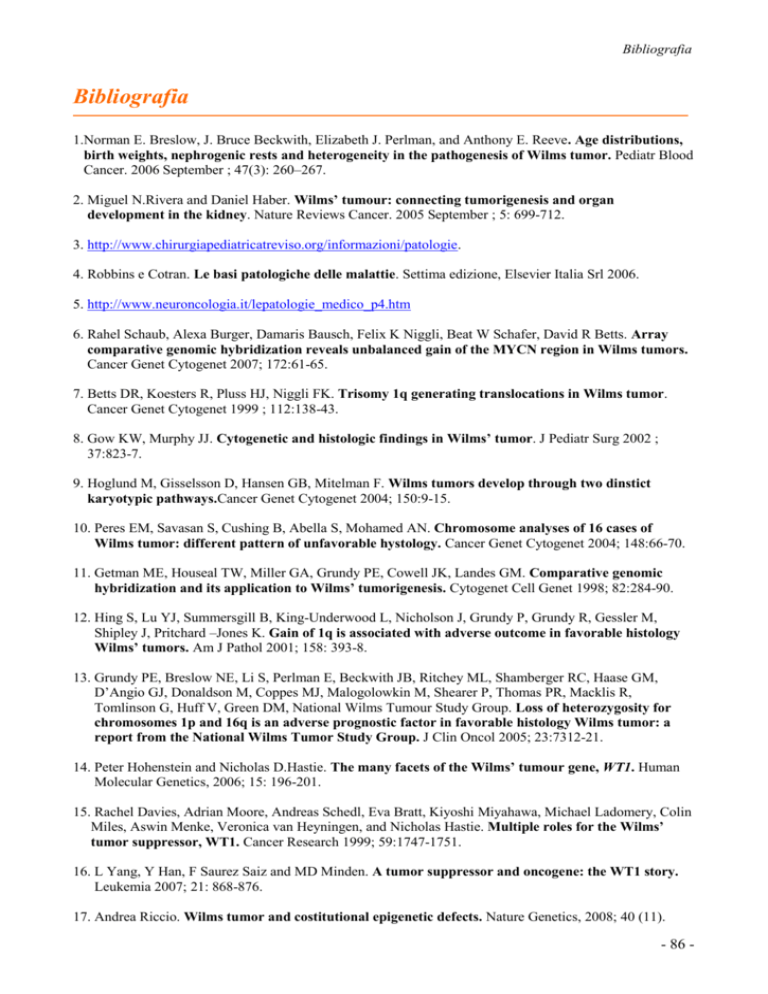

Bibliografia Bibliografia 1.Norman E. Breslow, J. Bruce Beckwith, Elizabeth J. Perlman, and Anthony E. Reeve. Age distributions, birth weights, nephrogenic rests and heterogeneity in the pathogenesis of Wilms tumor. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006 September ; 47(3): 260–267. 2. Miguel N.Rivera and Daniel Haber. Wilms’ tumour: connecting tumorigenesis and organ development in the kidney. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2005 September ; 5: 699-712. 3. http://www.chirurgiapediatricatreviso.org/informazioni/patologie. 4. Robbins e Cotran. Le basi patologiche delle malattie. Settima edizione, Elsevier Italia Srl 2006. 5. http://www.neuroncologia.it/lepatologie_medico_p4.htm 6. Rahel Schaub, Alexa Burger, Damaris Bausch, Felix K Niggli, Beat W Schafer, David R Betts. Array comparative genomic hybridization reveals unbalanced gain of the MYCN region in Wilms tumors. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2007; 172:61-65. 7. Betts DR, Koesters R, Pluss HJ, Niggli FK. Trisomy 1q generating translocations in Wilms tumor. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1999 ; 112:138-43. 8. Gow KW, Murphy JJ. Cytogenetic and histologic findings in Wilms’ tumor. J Pediatr Surg 2002 ; 37:823-7. 9. Hoglund M, Gisselsson D, Hansen GB, Mitelman F. Wilms tumors develop through two dinstict karyotypic pathways.Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2004; 150:9-15. 10. Peres EM, Savasan S, Cushing B, Abella S, Mohamed AN. Chromosome analyses of 16 cases of Wilms tumor: different pattern of unfavorable hystology. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2004; 148:66-70. 11. Getman ME, Houseal TW, Miller GA, Grundy PE, Cowell JK, Landes GM. Comparative genomic hybridization and its application to Wilms’ tumorigenesis. Cytogenet Cell Genet 1998; 82:284-90. 12. Hing S, Lu YJ, Summersgill B, King-Underwood L, Nicholson J, Grundy P, Grundy R, Gessler M, Shipley J, Pritchard –Jones K. Gain of 1q is associated with adverse outcome in favorable histology Wilms’ tumors. Am J Pathol 2001; 158: 393-8. 13. Grundy PE, Breslow NE, Li S, Perlman E, Beckwith JB, Ritchey ML, Shamberger RC, Haase GM, D’Angio GJ, Donaldson M, Coppes MJ, Malogolowkin M, Shearer P, Thomas PR, Macklis R, Tomlinson G, Huff V, Green DM, National Wilms Tumour Study Group. Loss of heterozygosity for chromosomes 1p and 16q is an adverse prognostic factor in favorable histology Wilms tumor: a report from the National Wilms Tumor Study Group. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23:7312-21. 14. Peter Hohenstein and Nicholas D.Hastie. The many facets of the Wilms’ tumour gene, WT1. Human Molecular Genetics, 2006; 15: 196-201. 15. Rachel Davies, Adrian Moore, Andreas Schedl, Eva Bratt, Kiyoshi Miyahawa, Michael Ladomery, Colin Miles, Aswin Menke, Veronica van Heyningen, and Nicholas Hastie. Multiple roles for the Wilms’ tumor suppressor, WT1. Cancer Research 1999; 59:1747-1751. 16. L Yang, Y Han, F Saurez Saiz and MD Minden. A tumor suppressor and oncogene: the WT1 story. Leukemia 2007; 21: 868-876. 17. Andrea Riccio. Wilms tumor and costitutional epigenetic defects. Nature Genetics, 2008; 40 (11). - 86 - Bibliografia 17b. Jeffrey S.Dome, MD,and Max J.Coppes, MD, PhD. Recent advances in Wilms tumor genetics. Curr Opin Pediatr 2002; 14: 5-11. 18. E. Cristy Ruteshouser, Stephen M. Robinson, and Vichi Huff. Wilms Tumor Genetics: Mutations in WT1, WTX and CTNNB1 Account for Only About One-Third of Tumors. Genes Chromosomes and Cancer 2008; 47:461-470. 19. Sourindra Maiti, Rita Alam, Christopher I. Amos, and Vichi Huff. Frequent association of -catenin and WT1 mutations in Wilms’ tumors. Cancer Research 2000; 60:6288-6292. 20. Brigitte Royer-Pokora , Angela Weirich, Valerie Schumacher, Constanzeschkereit, Manfred Beier, Ivo Leuschner, Noebert Graf, Frank Autschbach, Dominique Schneider, Melissa von Harrach. Clinical Relevance of Mutations in the Wilms Tumor Suppressor 1 Gene WT1 and the Cadherin-associated Protein 1 Gene CTNNB1 for Patients With Wilms Tumors. Results of Long-term Surveillance of 71 Patients International Society of Pediatric Oncology Study 9/Society for Pediatric Oncology. American Cancer Society, 2008; 113 (5): 893-6. 21. V. Schumacher, S. Schneider, A. Figge, G. Wildhardt, D. Harms, D. Schmidt, A. Weirich, R. Ludwig, and B. Royer-Pokora. Correlation of germ-line mutations and two-hit inactivation of the WT1 gene with Wilms tumors of stromal-predominant histology. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA 1997; 94:3972-3977. 22. Ihor V. Yosypiv and Samir S. El-Dahr. Role of the renin-angiotensin system in the development of the ureteric bud and renal collecting system. Pediatr Nephrol 2005; 20: 1219-1229. 23. Christopher R. Burrow. Regulatory molecules in kidney development. Pediatr Nephrol 2000; 14: 240253. 24. Gregory R. Dressler. The Cellular Basis of Kidney Development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2006; 22: 509-529. 25. Mélanie Béland, Maxime Bouchard. PAX gene function during kidney tumorigenesis: a comparative approach. Bull Cancer 2006; 93 (9): 875-82. 26. Dehbi M, Ghahremani M, Lechner M, Dressler G, Pelletier J. The paired-box trascription factor, PAX2, positively modulates expression of the Wilms’ tumor suppressor gene (WT1). Oncogene 1996; 13: 447-53. 27. Dehbi M, Pelletier J. PAX8-mediated activation of the wt1 tumor suppressor gene. EMBO J 1996; 15: 4297-306. 28. Dressler GR, Wilkinson JE, Rothenpieler UW, Patterson LT, Williams-Simons L, Westphal H. Deregulation of Pax-2 expression in transgenic mice generates severe kidney abnormalities. Nature 1993; 362: 65-7. 29. Porter JA, Ekker SC, Park WJ, Kessler DP von, Young KE, Chen CH, Ma Y, Woods AS, Cotter RJ, Koonin EV, Beachy PA (1996). Hedgehog patterning activity: role of a lipophilic modification mediated by the carboxy-terminal autoprocessing domain. Cell 86: 21-34. 30. Johnston RL, Scott MP (1998). New players and puzzles in the Hedgehog signaling pathway. Curr Opin Genet Dev 8: 450-456. 31. Chiang C, Litingtung Y, Lee E, Young KE, Corden JL, Westphal H, Beachy PA (1996). Cyclopia and defective axial patterning in mice lacking Sonic Hedgehog gene function. Nature 383: 407-413. 32. Kohlhase J, Wischermann A, Reichenbach H, Froster U, Engel W (1998). Mutations in tha SALL1 putative transcription factor gene cause Townes-Brocks syndrome. Nat Genet 18: 81-83. - 87 - Bibliografia 33. Willert K,Nusse R (1998). Beta-catenin: a key mediator of Wnt signaling. Curr Opin Genet Dev 8: 95102. 34. Kispert A, Vainio S, Shen L, Rowitch DH, McMahon AP, (1996). Proteoglycans are required for maintenance of Wnt-11 expression in the ureter tips. Development 122: 3627-3637. 35. Zeng L, Fagotto F, Zhang T, Hsu W, Vasicek TJ, Perry WL, Lee JJ, Tilghman SM, Gumbiner BM, Costantini F (1997). The mouse Fused locus encodes Axin, an inhibitor of the Wnt signaling pathway that regulates embryonic axis formation. Cell 90: 181-192. 36. Massague J (1996). TGFbeta signaling: receptors, transducers, and Mad proteins. Cell 85: 947-950. 37. Kretzschmar M, Massague J (1998) SMADs: mediators and regulators of TGF-beta signaling. Curr Opin Genet Dev 8: 103-111. 38. Vukicevic S, Kopp JB, Luyten FP, Sampath TK (1996). Induction of nephrogenic mesenchyme by osteogenic protein 1 (bone morphogenetic protein 7). Procl Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 9021-9026. 39. Ritvos O, Tuuri T, Eramaa M, Sainio K, Hilden K, Saxen L, Gilbert SF (1995). Activin disrupts epithelial branching morphogenesis in developing glandular organs of the mouse. Mech Dev 50: 229-245. 40. Piscione TD, Yager TD, Gupta IR, Grinfeld B, Pei Y, Attisano L, Wrana JL, Rosenblum ND (1997). BMP-2 and OP-1 exert direct and opposite effects on renal branching morphogenesis. Am J Physiol 273: F961-F975. 41. Sally Metsuyanim, et al. Accumulation of malignant renal stem cells is associated with epigenetic changes in normal renal progenitor genes. Stem Cells 2008; 26: 1808-1817. 42. Chi-Ming Li, et al. Gene expression in Wilms’ tumor mimics the earliest committed stage in the metanephric Mesenchymal-Epithelial Transition. Am J. Pathol 2002; 160(2): 2181-90. 43. Wenliang Li, et al. Transcript profiling of Wilms timors reveals connections to kidney morphogenesis and expression patterns associated with anaplasia. Oncogene 2005; 24: 457-68. 44. Vichi Huff. Wilms Tumor Genetics: A New, UnX-pected Twist to the Story. Cancer Cell 2007; 11: 105-107. 45. Roel Nusse. Converging on -catenin in Wilms tumor. Science 2007; 316: 988-89. 46. Stéphane Angers. WTX, un nouveaux gène suppresseur de tumeur muté dans la tumeur de Wilms. Médecine/Science 2007; 23(11). 47. D Perotti, B Gamba, M Sardella, F Spreafico, M Terenziani, P Collini, A Pession, M Nantron, F FossatiBellani and P Radice, on behalf of the AIEOP Wilms’ Tumor Study Group. Functional inactivation of the WTX gene is not a frequent event in Wilms’ tumors. Oncogene 2008; 27: 4625-4632. 48. Beckwith JB, Kiviat NB, Bonadio JF. Nephrogenic rests, nephroblastomatosis, and the pathogenesis of Wilms tumor. Pediatr Pathol 1990; 10: 1-36. 49. Beckwith JB. Nephrogenic rests and the pathogenesis of Wilms tumor: developmental and clinical considerations. Am J Med Genet 1998; 79: 268-73. 50. Beckwith JB. Precursor lesions of Wilms tumor: clinical and biological implications. Med Pediatr Oncol 1993; 21: 158-68. - 88 - Bibliografia 51. Ryuji Fukuzawa, Rosemary W Heathcott, Helen E More and Anthony E Reeve. Sequential WT1 and CTNNB1 mutations and alterations of -catenin localisations in intralobar nephrogenic rests and associated Wilms tumours: two case studies. J. Clin. Pathol 2007; 60: 1013-1016. 52. R Fukuzawa, MR Anaka, RW Heathcott, LA McNoe, IM Morison, EJ Perlman and AE Reeve. Wilms tumour histology is determined by distinct types of precursor lesions and not epigenetic changes. J Pathol 2008; 215: 377-387. 53. James I. Geller. Genetic Stratification of Wilms Tumor. Is WT1 Gene Analysis Ready for the Prime Time? American Cancer Society 2008; 113 (5):1080-9. 54. Sante Tura, Michele Baccarani, et al. Malattie del sangue e degli organi emopoietici. 3° edizione, Bologna; Esculapio 2003. 55. Grandori C, et al., The Myc/Max/Mad network and the trascriptional control of cell behavior. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol, 2000; 16: 653-99. 56. Dalla-Favera R, Wong-Staal F, and Gallo R.C. Oncogene amplification in promyelocytic leukaemia cell line HL-60 and primary leukaemic cells of the same patient. Nature 1982; 299 (5878): 61-3. 57. Magrath I. The pathogenesis of Burkitt’s lymphoma. Adv Cancer Res 1990; 55: 133-270. 58. Payne G.S., Bishop J.M., and H.E. Varmus. Multiple arrangements of viral DNA and an activated host oncogene in bursal lymphomas. Nature 1982;295 (5846):209-14. 59. Neil JC, et al. The role of feline leukaemia virus in naturally occurring leukaemias. Cancer Surv 1987;6(1): 117-37. 60. Vennstrom B, et al. Isolation and characterization of c-myc, a cellular homolog of the oncogene (vmyc) of avian myelocytomatosis virus strain 29. J Virol 1982; 42(3): 773-9. 61. Schwab M, et al. Amplified DNA with limited homology to myc cellular oncogene is shared by human neuroblastoma cell lines and a neuroblastoma tumour. Nature 1983; 305(5931): 245-8. 62. Nau M.M, et al. L-myc, a new myc-related gene amplified and expressed in human small cell lung cancer. Nature 1985; 318(6041): 69-73. 63. Sugiyama A, et al. Isolation and characterization of s-myc, a member of the rat myc gene family. Procl Natl Acad Sci USA 1989; 86(23): 9144-8. 64. Asai A, et al. The s-myc protein having the ability to induce apoptosis is selectively expressed in rat embryo chondrocytes. Oncogene 1994; 9(8): 2345-52. 65. Resar L.M., et al. B-myc inhibits neoplastic transformation and transcriptional activation by c-myc. Mol Cell Biol 1993; 13(2): 1130-6. 66. DePinho R.A, Schreiber-Agus N, and Alt F.W. Myc family oncogenes in the development of normal and neoplastic cells. Adv Cancer Res 1991; 57:1-46. 67. Kohl N.E, et al. Transposition and amplification of oncogene-related sequences in human neuroblastomas. Cell 1983; 35(2 Pt 1): 359-67. 68. Schwab M, et al. Chromosome localization in normal human cells and neuroblatomas of a gene related to c-myc. Nature 1984; 308(5956): 288-91. 69. Stanton L.W, and Bishop J.M. Alternative processing of RNA transcribed from NMYC. Mol Cell - 89 - Bibliografia Biol 1987; 7(12):4266-72. 70. Ramsay G, et al. Human proto-oncogene N-myc encodes nuclear proteins that bind DNA. Mol Cell Biol 1986; 6(12): 4450-7. 71. Slamon D.J, et al. Identification and characterization of the protein encoded by the human N-myc oncogene. Science 1986; 232(4751): 768-72. 72. Nakajima H, et al. Inactivation of the N-myc gene product by single amino acid substitution of leucine residues located in the leucine-zipper region. Oncogene 1989; 4(8): 999-1002. 73. Pession A, and Tonelli R. The MYCN oncogene as a specific and selective drug target for peripheral and central nervous system tumours. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2005; 5(4): 273-83. 74. Wenzel A, et al. The N-myc oncoprotein is associated in vivo with the phosphoprotein Max(p20/22) in human neuroblastoma cells. Embo J 1991; 10(12): 3703-12. 75. Ma A, eet al. DNA binding by N- and L-myc proteins. Oncogene 1993; 8(4): 1093-8. 76. Slack A, et al. The p53 regulatory gene MDM2 is a direct transcriptional target of MYCN in neuroblastoma. Procl Natl Acad Sci USA 2005; 102(3): 731-6. 77. Koskinen P.J, and Alitalo K. Role of myc amplification and overexpression in cell growth, differentiation and death. Semin Cancer Biol 1993; 4(1): 3-12. 78. Solomon D.L., Amati B, and Land H. Distinct DNA binding preferences for the c-Myc/Max and Max/Max dimers. Nucleic Acid Res 1993; 21(23): 5372-6. 79. Chang D:W., et al. The c-Myc transactivation domain is a direct modulator of apoptotic versus proliferative signals. Mol Cell Biol 2000; 20(12): 4309-19. 80. Hogarty M.D., et al. ODC1 is a critical determinant of MYCN oncogenesis and a therapeutic target in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res 2008; 68(23): 9735-45. 81. Slack A, and Shohet J.M. MDM2 as a Critical Effector of the MYCN Oncogene in Tumorigenesis. Cell Cycle 2005: 4(7): 857-860. 82. Brenner C, et al. Myc represses transcription through recruitment of DNA methyltransferase corepressor. Embo J 2005; 24(2): 336-46. 83. Adhikary S, and Eilers M. Transcriptional regulation and transformation by Myc proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2005; 6(8): 635-45. 84. Wakamatsu Y, et al. Regulation of the neural crest cell fate by N-myc: promotion of ventral migration and neuronal differentiation. Development 1997; 124(10): 1953-62. 85. Schwab M, and Bishop J.M. Sustained expression of the human proto-oncogene MYCN rescues rat embryo cells from senescence. Procl Natl Acad Sci USA 1988; 85(24): 9585-9. 86. Weiss W.A., et al. Targeted expression of MYCN causes neuroblastoma in transgenic mice. Embo J 1997; 16(11): 2985-95. 87. Hansford LM, et al. Mechanism of embryonal tumor initiation: distinct roles for Mycn expression and Mycn amplification. Procl Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101: 12664-9. 88. Schwab M. MYCN in neuronal tumours. Cancer Letters 2004; 204: 179-187. - 90 - Bibliografia 89. Nisen P.D., et al. N-myc oncogene RNA expression in neuroblastoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 1988; 80(20): 1633-7. 90. Pession A, et al. N-myc amplification and cell proliferation rate in human neuroblastoma. J Pathol 1997; 183(3): 339-44. 91. Brodeur G.M. Neuroblastoma: biological insights into a clinical enigma. Nat Rev Cancer 2003; 3(3): 203-16. 92. Lee W.H., Murphree A.L., and Benedict W.F. Expression and amplification of the N-myc gene in primary retinoblastoma. Nature 1984; 309(5967): 458-60. 93. Aldosari N, et al. MYCC and MYCN oncogene amplification in medulloblastoma. A fluorescence in situ hybridization study on paraffin sections from the Children’s Oncology Group. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2002; 126(5): 540-4. 94. Hui A.B., et al. Detection of multiple gene amplifications in glioblastoma multiforme using arraybased comparative genomic hybridization. Lab Invest 2001; 81(5): 717-23. 95. Strieder V, and Lutz W. Regulation of N-myc expression in development and disease. Cancer Letter 2002; 180(2): 107-19. 96. Lui W.O, Tanenbaum D.M., Larsson C. High level amplification of 1p32-33 and 2p22-24 in small cell lung carcinomas. Int J Oncol 2001; 19(3): 451-7. 97. Mao X, et al. Genetic alterations in primary cutaneous CD30+ anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Genes Chromosome Cancer 2003; 37(2): 176-85. 98. Mizukami Y, et al. N-myc protein expression in human breast carcinoma: prognostic implications. Anticancer Res 1995; 15(6b): 2899-905. 99. Van Lohuizen M, et al. N-myc is frequently activated by proviral insertion in MuLV-induced T cell lymphomas. Embo J 1989; 8: 133-6. 100. Sheppard RD, et al. Transgenic N-myc mouse model for indolent B cell lymphoma: tumor characterization and analysis of genetic alterations in spontaneous and retrovirally accelerated tumors. Oncogene 1998; 17: 2073-85. 101. Hirvonen H, et al. L-myc and N-myc proto-oncogenes in human leukemia cell lines. Blood 1991; 78: 3012-20. 102. Hirvonen H, et al. L-myc and N-myc in hematopoietic malignancies. Leuk Lymphoma 1993; 11: 197-205. 103. Kawagoe H, et al. Conditional MN1-TEL knock-in mice develop acute myeloid leukemia in conjunction with overexpression of HOXA9. Blood 2005; 106: 4269-77. 104. Kawagoe H, et al. Overexpression of N-myc rapidly causes acute myeloid leukemia in mice. Cancer Res 2007; 67(22): 10677-85. 105. Elsasser A, et al. AML1-ETO in acute myeloid leukemia with traslocation t(8;21) induces c-jun protein expression via the proximal AP-1 site of the c-jun promoter in an indirect, JNK-dependent manner. Oncogene 2003; 22: 5646-57. 106. http://www.stjude.org - 91 - Bibliografia 107. Hartman AD, et al. Constitutive c-jun N-terminal kinase activity in acute myeloid leukemia derives from Flt3 and affects survival and proliferation. Exp Hematol 2006; 34: 1360-76. 108. Raitano AB, et al. The Bcr-Abl leukemia oncogene activates Jun kinase and requires Jun for transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995; 92: 11746-50. 109. Rangatia J, et al. Elevated c-Jun expression in acute myeloid leukemias inhibits C/EBPa DNA binding via leucine zipper domain interaction. Oncogene 2003; 22: 4760-4. 110. Smeal T, et al. Oncogenic and transcriptional cooperation with Ha-Ras requires phosphorilation of c-Jun on serine 63 and 73. Nature 1991; 354: 494-6. 111. Hermeking H, et al. Identification of CDK4 as a target of c-MYC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000; 97: 2229-34. 112. Carlton M. Bates. Kidney development: regulatory molecules crucial to both mice and men. Mol Gene Metabol 2000; 71: 391-396. 113. Bates CM, et al. Role of N-myc in the developing mouse kidney. Dev Biol 2000; 222: 317-325. 114. Patterson LT, et al. The regulation of kidney development: new insights from an old model. Curr Opin Genet Dev 1994; 4: 696-702. 115. Dressler GR, et al. Deregulation of Pax-2 expression in transgenic mice generates severe kidney abnormalities. Nature 1993;362: 65-7. 116. Dziarmaga A, et al. Renal hypoplasia: lessons from Pax2. Pediatr Nephrol 2006; 21: 26-31. 117. Dziamarga A, et al. Suppression of ureteric bud apoptosis rescues nephron endowment and adult renal function in Pax2 mutant mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17: 1568-75. 118. Shao-Ling Zhang, et al. Pax-2 and N-myc regulate epithelial cell proliferation and apoptosis in a positive feedback loop. Pediatr Nephrol 2007; 22: 813-24. 119. Benjamin Dekel, et al. Multiple imprinted and stemness genes provide a link between normal and tumor pregenitor cells of the developing human kidney. Cancer Res 2006; 66(12): 6040-49. 120. Eric Yuan, et al. Genomic profiling maps loss of heterozygosity and defines the timing and stage dependance of epigenetic and genetic events in Wilms’ tumors. Mol Cancer Res 2005; 3(9): 493-502. 121. Perry D. Nisen, et al. Enhanced expression of the N-myc gene in Wilms’ tumors. Cancer Res 1986; 46: 6217-22. 122. Anu Gupta, et al. Regulation of CRABP-II expression by MycN in Wilms tumor. Exp Cell Res 2008; 314: 3663-68. 123. B. Zirn, et al. Expression profiling of Wilms tumors reveals new candidate genes for different clinical parameters. Int J. Cancer 2006; 118: 1954-62. 124. Zirn B, et al. All-trans retinoic acid treatment of Wilms tumor cells reverses expression of genes associated with high risk and relapse in vivo. Oncogene 2005; 24: 5246-51. 125. U. Galderisi, et al. Differentiation and apoptosis of neuroblastoma cells: role of N-myc gene product. J Cell Biochem 1999; 73: 97-105. - 92 - Bibliografia 126. Burkhart CA, et al. Effects on MYCN antisense oligonucleotide administration on tumorigenesis in a murine model of neuroblastoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003; 95(18): 1394-403. 127. T. Matsuo, C J Thiele. p27(Kip1): a key mediator of retinoic acid induced growth arrest in the SMSKCNR human neuroblastoma cell line. Oncogene 1998; 16: 3337-43. 128. F.M Balis. Evolution of anticancer drug discovery and the role of cell-based screening. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002; 94: 78-79. 129. T. Berg, et al. Small-molecule antagonists of Myc/Max dimerisation inhibit Myc-induced transformation of chicken embryo fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002; 99: 3830-35. 130. Xiaohong Lu, et al. The MYCN oncoprotein as a drug development target. Cancer Leters 2003; 197: 125-30. 131. Auvinen M, et al. Ornithine decarboxylase activity is critical for cell transformation. Nature 1992; 360: 355-8. 132. Pegg AE. Polyamine metabolism and its importance in neoplastic growth and a target for chemotherapy. Cancer Res 1998; 48: 759-74. 133. Bettuzzi S, et al. Coordinate changes in of polyamine metabolism regulatory proteins during the cells cycle of normal human dermal fibroblasts. FEBS Lett 1999; 446: 18-22. 134. Gerner EW, et al. Polyamines and cancer: old molecules, new understandings. Nat Rev Cancer 2004; 4: 781-92. 135. Wallick CJ, et al. Key role for p27Kip1, retinoblatoma protein Rb, and MYCN in polyamine inhibitor-induced G1 cell cycle arrest in MYCN-amplified human neuroblastoma cells. Oncogene 2005; 24: 5606-18. 136. Stevenson FK. Update on cancer vaccines. Curr Opin Oncol 2005; 17(6): 573-7. 137. Nielsen PE, et al. Sequence-selective recognition of DNA by strand displacement with thymine substituted polyamide. Science 1991; 254(5037): 1497-500. 138. Egholm M, et al. PNA hybridizes to complementary oligonucleotides obeying the Watson-Crick hydrogen-binding rules. Nature 1993; 365(6446): 566-8. 139. Egholm M, et al. Efficient pH-independent sequence-specific DNA binding by pseudoisocytosinecontaining bis-PNA. Nucleic Acids Res 1995; 23(2): 217-22. 140. Demidov VV, et al. Stability of peptide nucleic acids in human serum and cellular extracts. Biochem Pharmacol 1994; 48(6): 1310-3. 141. Merrifield B. Solid phase synthesis. Science 1986; 232(4748): 341-7. 142. Christensen L, et al. Solid-phase synthesis of peptide nucleic acids. J Pept Sci 1995; 1(3): 175-83. 143. Uhlmann E. Peptide nucleic acids (PNA) and PNA-DNA chimeras: from high binding affinity towards biological function. Biol Chem 1998; 379(8-9): 1045-52. 144. Eriksson M, et al. Sequence dependent N-terminal rearrangement and degradation of peptide nucleic acid (PNA) in aqueous solution. Nouv J Chim 1998; 22: 1055-9. 145. Hyrup B, and Nielsen PE. Peptide nucleic acids (PNA): synthesis, properties and potential - 93 - Bibliografia applications. Bioorg Med Chem 1996; 4(1): 5-23. 146. Kurg R, et al. Inhibition of the bovine papillomavirus E2 protein activity by peptide nucleic acid. Virus Res 2000; 66(1): 39-50. 147. Kuhn H, et al. Kinetic sequence discrimination of cation bis-PNAs upon targeting of doublestranded DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 1998; 26(2): 582-7. 148. Brown SC, et al. NMR solution structure of a peptide nucleic acid complexed with RNA. Science 1994; 265(5173): 777-80. 149. Nielsen PE, et al. Peptide nucleic acids (PNAs): potential antisense and anti-gene agents. Anticancer Drug Des 1993; 8(1): 53-63. 150. Vickers TA, et al. Inhibition of NF-kappa B specific transcriptional activation by PNA strand invasion. Nucleic Acids Res 1995; 23(15): 3003-8. 151. Ray A, and B Norden. Peptide nucleic acid (PNA): its medical and biotechnical applications and promise for the future. Faseb J 2000; 14(9): 1041-60. 152. Karkare S, and Bhatnagar D. Promising nucleic acid analogs and mimics: characteristic features and applications of PNA, LNA and morpholino. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2006; 71(5): 575-86. 153. Knudsen H, and Nielsen PE. Antisense properties of duplex- and triplex-forming PNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 1996; 24(3): 494-500. 154. Mologni L, et al. Additive antisense effects of different PNAs on the in vitro translation of the PML/RAR gene. Nucleic Acids Res 1998; 26(8): 1934-8. 155. Aldrain-Herrada G, et al. A peptide nucleic acid (PNA) is more rapidly internalized in cultured neurons when coupled to a retro-inverso delivery peptide. The antisense activity depresses the target mRNA and protein in magnocellular oxytocin neurons.Nucleic Acids Res 1998;26(21):4910-6. 156. Tyler BM, et al. Specific gene blockade shows that peptide nucleic acids readily enter neuronal cells in vivo. FEBS Lett 1998; 421(3): 280-4. 157. Boffa LC, et al. Invasion of the CAG triplet repeats by a complementary nucleic acid inhibits transcription of the androgen receptor and TATA-binding protein genes and correlates with refolding of an active nucleosome containing a unique AR gene sequence. J Biol Chem 1996; 271(22): 13228-33. 158. Norton JC, et al. Inhibition of human telomerase activity by peptide nucleic acids. Nat Biotechnol 1996; 14(5): 615-9. 159. Faruqi AF, et al. Peptide nucleic acid-targeted mutagenesis of a chromosomal gene in mouse cells. Procl Natl Acad Sci USA 1998; 95(4): 1398-403. 160. Branden LJ, et al. A peptide nucleic acid-nuclear localization signal fusion that mediates nuclear transport of DNA. nat Biotechnol 1999; 17(8): 784-7. 161. Nastruzzi C, et al. Liposomes as carriers for DNA-PNA hybrids. J Control Release 2000;68(2):237-49. 162. Pooga M, et al. Cell penetration by transportan. Faseb J 1998; 12(1): 67-77. 163. Cutrona G, et al. Effects in live cells of a c-myc anti-gene PNA linked to a nuclear localization signal. Nat Biotechnol 2000; 18(3): 300-3. - 94 - Bibliografia 164. Hamilton SE, et al. Cellular delivery of a peptide nucleic acids and inhibition of human telomerase. Chem Biol 1999; 6(6): 343-51. 165. Hanvey JC, et al. Antisense and antigene properties of peptide nucleic acids. Science 1992; 258(5087): 1481-5. 166. Koppelhus U, et al. Efficient in vitro inhibition of HIV-1 gag reverse transcription by peptide nucleic acid (PNA) at minimal ratios PNA/RNA. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25(11):2167-73. 167. Fiandaca MJ, et al. Self-reporting PNA/DNA for primers PCR analysis. Genome Res 2001; 11(4): 609-13. 168. Orum H, et al. Single base pair mutation analysis by PNA directed PCR clamping. Nucleic Acids Res 1993; 21(23): 5332-6. 169. Pession A, et al. Targeted inhibition of NMYC by peptide nucleic acid in N-myc amplified human neuroblastoma cells: cell cycle inhibition with induction of neuronal cell differentiation and apoptosis. Int J Oncol 2004;24(2): 265-72. 170. Tonelli R; et al. Anti-gene peptide nucleic acid specifically inhibits MYCN expression in human neuroblastoma cells leading to cell growth inhibition and apoptosis. Mol Cancer Ther 2005; 4(5): 779-86. - 95 - Bibliografia - 96 -