Memory: Encoding, Storage, and Retrieval

advertisement

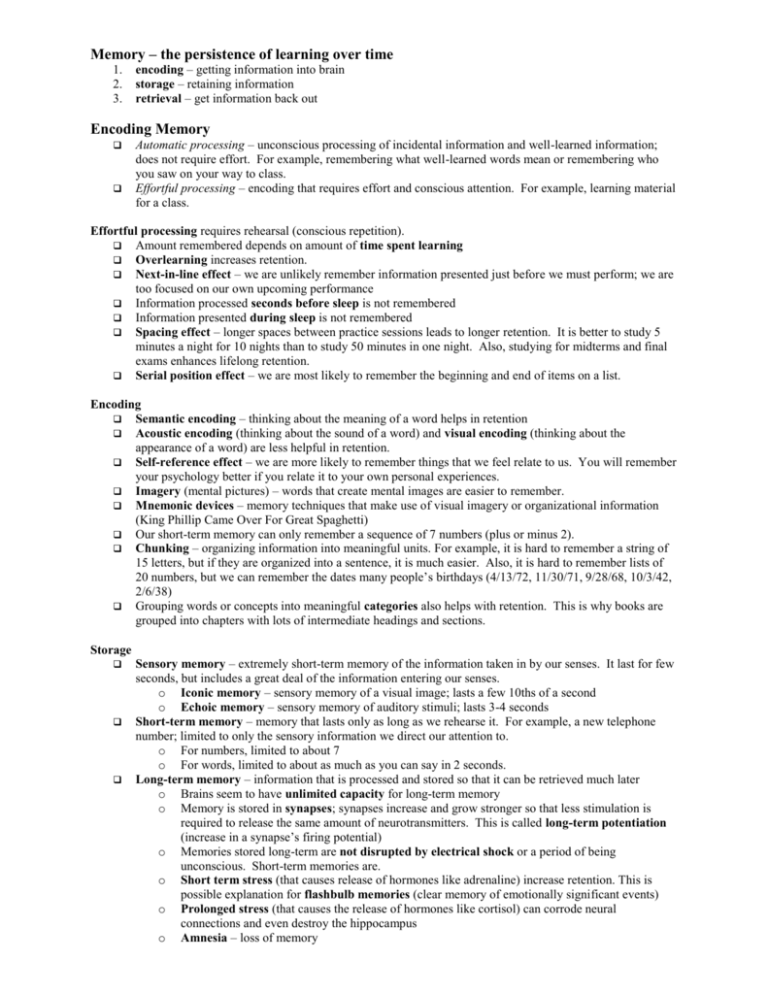

Memory – the persistence of learning over time 1. 2. 3. encoding – getting information into brain storage – retaining information retrieval – get information back out Encoding Memory Automatic processing – unconscious processing of incidental information and well-learned information; does not require effort. For example, remembering what well-learned words mean or remembering who you saw on your way to class. Effortful processing – encoding that requires effort and conscious attention. For example, learning material for a class. Effortful processing requires rehearsal (conscious repetition). Amount remembered depends on amount of time spent learning Overlearning increases retention. Next-in-line effect – we are unlikely remember information presented just before we must perform; we are too focused on our own upcoming performance Information processed seconds before sleep is not remembered Information presented during sleep is not remembered Spacing effect – longer spaces between practice sessions leads to longer retention. It is better to study 5 minutes a night for 10 nights than to study 50 minutes in one night. Also, studying for midterms and final exams enhances lifelong retention. Serial position effect – we are most likely to remember the beginning and end of items on a list. Encoding Semantic encoding – thinking about the meaning of a word helps in retention Acoustic encoding (thinking about the sound of a word) and visual encoding (thinking about the appearance of a word) are less helpful in retention. Self-reference effect – we are more likely to remember things that we feel relate to us. You will remember your psychology better if you relate it to your own personal experiences. Imagery (mental pictures) – words that create mental images are easier to remember. Mnemonic devices – memory techniques that make use of visual imagery or organizational information (King Phillip Came Over For Great Spaghetti) Our short-term memory can only remember a sequence of 7 numbers (plus or minus 2). Chunking – organizing information into meaningful units. For example, it is hard to remember a string of 15 letters, but if they are organized into a sentence, it is much easier. Also, it is hard to remember lists of 20 numbers, but we can remember the dates many people’s birthdays (4/13/72, 11/30/71, 9/28/68, 10/3/42, 2/6/38) Grouping words or concepts into meaningful categories also helps with retention. This is why books are grouped into chapters with lots of intermediate headings and sections. Storage Sensory memory – extremely short-term memory of the information taken in by our senses. It last for few seconds, but includes a great deal of the information entering our senses. o Iconic memory – sensory memory of a visual image; lasts a few 10ths of a second o Echoic memory – sensory memory of auditory stimuli; lasts 3-4 seconds Short-term memory – memory that lasts only as long as we rehearse it. For example, a new telephone number; limited to only the sensory information we direct our attention to. o For numbers, limited to about 7 o For words, limited to about as much as you can say in 2 seconds. Long-term memory – information that is processed and stored so that it can be retrieved much later o Brains seem to have unlimited capacity for long-term memory o Memory is stored in synapses; synapses increase and grow stronger so that less stimulation is required to release the same amount of neurotransmitters. This is called long-term potentiation (increase in a synapse’s firing potential) o Memories stored long-term are not disrupted by electrical shock or a period of being unconscious. Short-term memories are. o Short term stress (that causes release of hormones like adrenaline) increase retention. This is possible explanation for flashbulb memories (clear memory of emotionally significant events) o Prolonged stress (that causes the release of hormones like cortisol) can corrode neural connections and even destroy the hippocampus o Amnesia – loss of memory o o o o Implicit memory – retention without conscious recollection (skills), like how to tie shoes Explicit memory – memory of facts and experiences, like knowing the functions of the parts of the brain Hippocampus is the temporary processing center for storing explicit memories; once formed, the memories are stored in the frontal and temporal lobes of the cortex The cerebellum is involved in forming implicit memories. Retrieval We can recognize more than we can recall. Once we’ve learned something and forgotten it, it takes less time to relearn it. Recognition is easier than recall because it provides retrieval cues or hints that help us remember where the information is stored in our memory. Priming – the activation of particular associations in our memory; is often unconscious. For example, we may suddenly remember something that we thought we had forgotten when we smell or taste something associated with the memory. In this case, the smell is priming our memory Context effects – we are more likely to remember something if we learn it in the same context. For example, you will likely do better on a psychology test if you take it in this room. State-dependent memory – we are more likely to remember something if we are in the same psychological state (happy, sad, etc) that we were in when we learned it. Memories are mood-congruent – that is, if we are in a good mood, we are more likely to recall events as positive. If we are in a bad mood, we are more likely to recall events as negative. This is true even if we are recalling the SAME event in two different states of mind. For example, lets say you went on a family vacation to the beach and there were tons of mosquitoes and your parents never let you out of their sight, and the weather and beach was beautiful. If someone asks you about your vacation later, what aspects of it you will remember (the bad or good ones) depends on your current mood. Mood-congruent memories explain how depression can easily become a downward spiral. A person in a depressed mood recalls or interprets events negatively, thus leaving them feeling even worse. Forgetting – Forgetting is an important adaptation. If we couldn’t forget most of the information that enters our senses, we would be distracted most of the time. Why do we forget? 1. Encoding Failure – information never enters long-term memory; usually because we didn’t make an effort to pay attention and rehearse the information 2. Storage Decay – memories that are not used and rehearsed are forgotten (do you remember freshman biology?) The “forgetting curve” indicates that over 50% of what we learn is forgotten quickly if not used, but the remainder sticks with us for a long time. For example, if you are taking Spanish and then don’t take it in college, you will likely forget most of what you learned by your sophomore year. However, the information you still remember in two years will stick with your for most of the rest of your life! 3. Retrieval Failure – inability to “locate” memories; tip of the tongue phenomenon; commonly associated with memory loss in old age. Interference – learning that interferes with retrieving other information o Proactive interference (forward acting interference) – the disruptive effect of prior learning on the recall of new information. For example, if I were to give you a list of 5 words to memorize, it would be easy. But if I followed it with a new list of 5 words every hour, it would get harder and harder. o Retroactive interference (backward-acting interference) – the disruptive effect of new learning on the recall of old information. This is common in AP Biology. Once I give students the minute details of a process, they tend to forget the simple basics they understood well freshman year. Motivated Forgetting (repression) – it has been suggested that people repress memories that are painful or that conflict with their self-image. For example, if I view myself as a kind and caring person, I may forget about the cruel things I did to my sister as a child. Memory Construction – Do we create false memories? Misinformation Effect – If we are primed with misleading information, we are likely to incorporate it into our memory; As we retell stories, we will fill make guesses about memory gaps. These guesses then become part of our memory. Source Amnesia – Attributing an event to the wrong source. This could be attributing an imagined event to real life or attributing a story read in a book to your own childhood. Ronald Reagan story How can we tell if memories are true or false? The hippocampus is equally active when a person recounts true and false memories. However, other areas (such as association areas) are only active when a person recounts a true memory. Eye Witness Accounts Self-assurance and confidence are NOT good indicators of how likely one’s memories are to be true. Hypnotically refreshed memories are susceptible to the misinformation effect (from leading questions) and are not more likely to be true than other memories. Eyewitness testimony is most likely to be accurate if a neutral person who asks non-leading questions performs the interview.