Deadwood: A Story of Movement and Change

Deadwood

A Story of Movement and Change

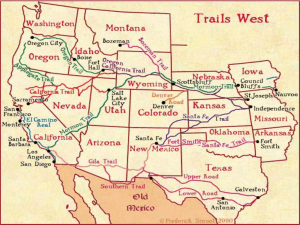

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 kept the Black Hills region the heart of

Lakota land. But after the famous 1874 Custer expedition observed gold in the southern Black Hills, prospectors swarmed into the forbidden territory. Quickly, stagecoach routes were established from cities on the Union Pacific railroad.

Freight wagons from Cheyenne hauled in whatever the prospectors needed.

Illegal or otherwise, the Black Hills had a lot of traffic.

The northern Black Hills were not part of the gold rush until gold was discovered in Deadwood’s Whitewood Creek in early fall 1875. Almost overnight, gold camps in the southern Hills emptied. The first men who came into

Deadwood Gulch walked with a loaded burro or came in vehicles like this utility wagon ( #55 ). Prospectors moved their supplies with whatever vehicles they had.

Their work, like their wagons, was purely practical. Their camps were largely democratic, with rules for staking claims and using water. It was a first-come,

first-rewarded society, a perfect model of individual private enterprise. In a gold rush, everyone hoped to get rich.

Deadwood’s prospectors kept a sharp eye out for Lakota warriors who wanted them dead and U. S. Army troops who wanted them out. It was no place for corporations to begin operations but operate they did. Trains of freight wagons ( #2 ) pulled by multiple teams of oxen or lines of paired mules rolled into

Deadwood. On Fred Evans’ first attempts to get his “bull trains” into the Hills in

1876, the Army took his animals and burned his wagons. He persisted. In 1880, after the Black Hills were taken from the Lakota and absorbed into Dakota

Territory, Evans’ company, one of some twenty large companies, hauled seven million pounds of freight from Ft. Pierre on the Missouri River. When Wild Bill

Hickok and Calamity Jane arrived in June 1876, they came with a bull train. These legendary characters could not outpace corporate America.

Like the home offices of freight companies, stagecoach operators set up lines into Deadwood even before their routes were legal. Stagecoaches were all about profitable baggage, mail contracts, paying passengers and timetables.

They were also frequent targets of road agents (stagecoach robbers). The drama and danger of the early Black Hills described stagecoach travel more than any other aspect of the Deadwood story. This largely original coach ( #48 ), more

accurately called a mud wagon or hack wagon, embodied that story. It also helped to turn the gold camp into a proper city with other cargo: families.

Some of the earliest photographs of Deadwood record streets crowded with wagons, a sure sign of business activity. Some also show frontier junkyards of abandoned or partially dissembled vehicles. Early prospectors sometimes took apart their general purpose wagons ( #58 ) to make sluices and rockers. Lucky men bought newer ones. But not all prospectors were lucky. Only two years after the social equality of the first gold rush, a group of wives in Deadwood organized a relief society for homeless men.

By 1877, Deadwood was making the transition from a hastily-constructed gold camp to a center of commerce. But newspaper editors raised concerns. They urged the city to establish a hose company (fire department) and businesses to build with fire prevention in mind. The editors proved to be right. In September

1879, a raging fire turned almost all of downtown into a smoldering ruin. Humanpulled hose carts ( #57 ) and hydrants fed by water tanks proved inadequate.

Some citizens had the good sense to leave. Others began to rebuild before the ground was cool, according to newspaper accounts. Deadwood survived but it was not to be the last disastrous fire.

Remote as Deadwood was, entrepreneurs flocked to the city. Some of the most important businesses were sawmills. A pair of men could turn pine trees into boards with whip saws. One man stood above the log and the other sawed from below, often in a pit. By the summer of 1876 steam-powered rigs cutting with multiple blades made the two-man outfits obsolete. After the Great Fire of

1879, sawmills became big business. Lumber wagons ( #59 ) served the economic niche. This one is extendable and can nearly pivot in place. The specialized commercial vehicle was a sign of a developing economy.

The arrival of this “Loop Front” Phaeton carriage (# 17 ) was more evidence that money was being made in Deadwood. Having no brakes, a light-duty undercarriage, and room for only two passengers without cargo, it was not designed for the rugged roads of the Black Hills. It was a city vehicle. Limited as it must have been to certain roads and good weather, it still displayed the success of its owner. Such vehicles were a product of mass production in distant cities, were picked from a list of various models and came with options like rubber tires and interior trim. The kerosene lamps that came new with the vehicle said something more about Deadwood. The city was a safe place for socializing in the evening.

The grasslands east of the Black Hills were also profitable. By 1880, huge herds of beef cattle roamed unfenced government property that had been Lakota land only four years earlier. It was the last great open grassland on the continent.

Chuck wagons (# 8 ) were the field restaurants of mobile cowboy communities.

They were not part of the Deadwood story directly but cowboys were known to entertain themselves in the city and local entrepreneurs invested in the cattle industry. Deadwood banker Harris Franklin, for example, once owned 45,000 head of cattle, the largest herd in the northern United States at the time.

Deadwood in the 1880s had become a settled Victorian community by the time wagons like this (# 34 ) were seen on the streets. The vehicle could also negotiate both rugged roads and open country. The fully-restored “mountain wagon” was authentic to Black Hills geography, with brakes, heavy duty fourspring suspension, and triple reaches (front to back connectors). Made in Moline,

Illinois, it could carry a family with all the seats in. With seats removed, it became a freight vehicle. Neither a temporary vehicle like a prospector wagon nor an exclusive carriage like the Phaeton, it revealed a settled family culture.

The “Spider” Phaeton (# 37 ) suggests a higher income than the other

Phaeton (#17). Note the carefully-shaped wooden body, the elegant curves of the metal fixtures and the graceful lines of the undercarriage. Like any new car today,

it would have turned heads with its tasteful design and sparkling paint job. It was a very American expression of success, not ornate like the vehicles of the

European elite but a high-class version of a mass-produced carriage. Its manufacturer, Studebaker, was one of very few carriage companies that made the transition to automobile production.

After the Great Fire of 1879, most businesses rebuilt in brick and mortar, or had fireproof safes constructed in their buildings. City leaders also upgraded to more and better fire-fighting apparatus. Hose carts (# 42 ) were once state-of-theart firefighting equipment. Pulled by teams of men, they moved hoses and other tools to the hydrant nearest the site of a fire. Heavier gear was moved by horses.

Hose cart training led to an entertaining diversion: hose cart races on holidays.

But this vehicle also points to the broader hazards of Deadwood’s location. In both 1882 and 1883, floods devastated downtown, taking with them the brick structures designed to withstand fires.

This Portland cutter (# 53 ) was distinguished from the Albany sleigh by its squared back. Snow often shut down freight operations and stagecoach lines but

Deadwood did not stop moving. Snowy roads were sometimes flattened with large rollers so that cutters pulled by single horses could negotiate them.

Children who grew up in Deadwood had fond memories of all seasons, including

ice-skating, sledding and sleigh rides in winter. The town famous for its bawdy

Main Street was also safe for its children.

Despite its distance from major cities, Deadwood offered the highest fashions and newest diversions to its citizens. Women could order dresses from

New York or Paris. Men could buy Cuban cigars or Scotch whiskey. This 1880

Brougham coach (# 36 ) points to both Deadwood’s sophistication and the ability of some in the city to keep up with trends. The coach was a “Bachelor” model for two occupants only. The two sets of side windows allowed visibility (glass) or secrecy (wood). One of seventy models to choose from, this one came with silk interior trim, fine leather upholstery, umbrella holders, cigar boxes, vanities with mirrors and holders for calling cards. It was a Victorian social statement on wheels. It was also an urban vehicle. The spikes on the rear springs were intended to keep street kids from hitching rides.

The popularity of this Rockaway carriage (# 16 ) was attributed to the equality it suggested; the driver sat at the same level as the passenger. Unlike the

Brougham (#36), the Rockaway driver sat out of the rain and was probably a family member. But like the Brougham, it offered some of the finer aspects of private transportation; glass front windows, brass fittings and woven fabric trim.

Note the tasteful step cover. The vehicle would have fit into Deadwood’s model of success where very few came with money and many had the chance to do well.

This road cart (# 38 ) was not a racing sulky but it was built for speed. It was a frontier sports car. By the mid 1880s, Deadwood was prosperous enough that such things as horse racing and breeding race horses had established themselves.

Around the area and over the next decades, horsemen bred animals for all the tasks horses were expected to do: pull heavy farm equipment, drive cattle, carry soldiers, move mass transit vehicles (stagecoaches), win prizes at fairs and race.

A number of vehicles in the collection have no local history and little is known about them. But like this delivery wagon (# 4 9 ) they still tell the Deadwood story. The undercarriage and side fenders show this wagon was built more for volume and maneuverability than moving great weight. It points to private enterprise as the defining character of the city. Historic Deadwood photographs show streets lined with wholesale centers, retail stores and warehouses. By 1886 standard gauge railroads had reached Rapid City. While it would take four more years for trains to roll into Deadwood, local merchants knew the new technology was about to change their lives.

This milk wagon (# 1 ) is comparable to the previous carriage in that it was used elsewhere. It too was a specialized commercial vehicle. As an example of the

American tradition of home delivery, it carried milk from a dairy to individual homes (manufacturer to consumer). There is no seat for the milkman. He walked carrying bottles to and from each house, while his horse knew when to stop and where to turn. Historic photographs of 1880 Deadwood show similar carriages advertising a range of products and local owners.

The beer wagon (# 41 ) was another vehicle designed to carry a liquid but it served an entirely different commercial model. It moved beer in bulk from a brewery to saloons (manufacturer to retail outlet). The very structure of the wagon reveals an economic and social world apart from the milk wagon. Beer came to the area first. The first brewery was established in 1876, clearly a priority to gold camp residents. Many in early Deadwood were of northern European ancestries in which beer was a traditional beverage. What might have happened if most of the prospectors had been Italian or Greek? Vineyards and wagons for wine barrels?

A photograph of a Deadwood funeral in 1907 shows this 1890 Landau carriage (# 23 ). More than likely, it was owned by the funeral company and played the role a limo does today. Like other vehicles reserved for special occasions, this

carriage was both beyond the means of most families and derived from a lifestyle of considerable wealth. The Landau was developed in Germany as a formal, coach-class vehicle that would have required a driver and a groom to assist passengers. This one has so many original components that wagon experts have advised not using it in the annual Days of ’76 Parade.

Like a number of pieces of equipment in Deadwood’s historic fire departments, this chemical tank (# 56 ) was first an innovation and later an outdated piece of technology. It was too small for a house fire. However from the end of the 19 th Century and well into the 1900s, such chemical tanks were standard safety features in factories and warehouses. It held a stoppered bottle of sulfuric acid and around thirty gallons of water. At a fire site, the tank was tipped up, causing the acid and water to mix, creating carbon dioxide which was then spread with a hose onto the fire.

The railroad reached Deadwood in December 1890. Overnight, freight wagons became obsolete and overland stagecoach lines disappeared. But many other carriages only had more to carry, like this stake-bed dray wagon (# 6 ), with its removable side posts and heavy duty undercarriage. It was perfectly suited for loads of various weights, objects of any shape and backing up close to a train

station loading dock. The railroad propelled Deadwood into becoming the distribution hub of the region. Dray wagons were essential to this new status.

Hose carts (#57 and #42) moved hand tools and hoses to hydrants. Horses pulled side or steam-powered water pumpers to fires. Horse-drawn hook and ladder wagons (# 44 ) were largely used to save people from upper floors of buildings. They carried a variety of sizes and styles of ladders, along with poles for pushing or pulling structural members. In addition to bridging ladders, they brought extension ladders which could be leaned against a building or made free-standing with attached poles. Their designs were protected by law. Like most other wagons in the collection, this hook and ladder vehicle is a rolling assemblage of patent-protected inventions.

From Deadwood’s first days, when wagons had to be lowered into the gulches by ropes, to the present, when paved highways accommodate tour buses and motorcycles, roads have been vital to the city. This dump wagon (# 4 ) from around 1900 is a tribute to the road-building legacy. The famously muddy roads of early Deadwood were sometimes stabilized with perpendicular rows of tree trunks. Later entrepreneurs were given rights to establish toll roads. They collected fees and took responsibility for the quality of the road in their care. This dump wagon would have seen duty both for road construction and general

excavation. Historic photographs show dump wagons being used to make area roads suitable for automobiles. They helped to bring about their own end.

Like the extension of electrical power in the 20th century, the institution of home mail delivery in the late 1890s changed life in rural America profoundly.

Through vehicles like this inaccurately-restored mail wagon (# 4 6 ), farms and small towns had a new link to the broader world. But even huge bureaucracies come and go. The United States Postal Service once had seventy offices in

Deadwood’s Lawrence County. Now there are four. Home delivery was one of many facets of American life that were displaced by later technologies, most importantly the automobile.

The date of this convertible sleigh (# 20 ) is not recorded but a 1912 patent from a Hudson, South Dakota inventor describes a similar design. The invention reveals several trends in rural America at the turn of the century. First is the innovative culture of small towns and farms. Far from the conveniences of large cities, rural businessmen and farmers had to find practical solutions to problems on their own. Second, many pre-electrical inventions of the time could be manufactured by local blacksmiths and woodworkers. Third, it was an era when numerous creative individuals hoped to make money with their inventions.

Referred to in the Days of ’76 Parade as a band wagon, (# 9 ) this carriage might have served several functions. It could have carried members of a band and their instruments, but a historic wagon would have been painted with festive designs. In a larger city, such a vehicle would have served as mass transit, a turnof-the-century bus. In Deadwood, this carriage could easily have carried tourists.

Whether it was a vehicle used solely for music, a small city bus or a sightseeing carriage, this wagon would have indicated Deadwood was a mature, self-assured community.

The story of this unassuming “buggy” (# 26 ) dwarfs the vehicle itself. The black body looks like the many thousands of others mass-produced in eastern cities. But this one is metal, with decorative shapes stamped on the back. It was the product of an assembly line. Early makers of cars knew they stood at the threshold of a new era of transportation. Some also realized they could make money selling both cars and the carriages they replaced. Photographs from the early 1900s show what the transition looked like in Deadwood. Automobiles are seen winding their way between carriages and horse droppings.

Although the black hearse (# 12 ) was built around 1890, such vehicles were seen in Deadwood for the next thirty years. Formal traditions are often called upon in important life transitions, such as weddings, graduations, inaugural

events and funerals. At such times, we surround ourselves with ancient symbols, like the carved Greek columns on this hearse. After the assassination of President

Lincoln in 1865 and the national grief that followed, funeral practices became more complex and formal. This hearse is a tribute to that ongoing tradition.

Traditionally, a white hearse (# 13 ) would have carried the casket of a child.

This one is larger, suggesting modifications or other ceremonial uses. While formal decorations adorn the outside of the hearse, it had some modern components, including rollers to assist the removal of a casket and an ice tray to preserve the body though the funeral proceedings. Made in 1880, this vehicle has been used to bring honored Deadwood citizens to their final resting place as recently as 2010.

Few vehicles in the horse-drawn carriage era saw more demanding duty than this one (# 47 ). Referred to as a transfer wagon, it was used to carry extremely heavy loads short distances, often from a rail head to a work site. The Homestake

Gold Mining Company in Lead purchased this standard model and then thoroughly re-engineered it, as they were famous for doing. Homestake engineers replaced the large wood reaches with the pipe and I beams. Modified, the wagon could carry at least 10,000 pounds, as seen in a historic photograph of the Adams Museum’s J. B. Haggin locomotive riding on it. The wagon also

completes the story of the Black Hills gold rush. Prospectors arrived in 1875 on farm wagons loaded with hand tools and gear. Thirty years later wagons like this one show what gold mining had become: a complex, heavy industry requiring massive equipment and substantial investment by capitalists headquartered in distant large cities.

Similar to other vehicles in the collection, the Montgomery Ward wagon (# 7 ) carried far more than farm produce. It offered a glimpse into the national marketing and distribution network that was well established by the beginning of the 20 th century. Companies like Montgomery Ward and Sears sent catalogs to homes in all the states. Consumers could order everything from hairpins to complete houses. While this wagon dates from around 1930, it differs little from the first wagons in the Black Hills. Comparable wagons were in use until the

1950s, long after tractors had displaced horses. Throughout this era, the farm wagon embodied a way of life and a relationship to the land remembered warmly and celebrated into the present.

Before the 1920s, Deadwood’s core streets had been covered with brick pavers and area roads were being upgraded to accommodate increasing numbers of automobiles. Along with greater commercial traffic, tourists were arriving in numbers to view the sites of the Black Hills. Among the visitors was

Buffalo Bill Cody. Cody was already world famous as the preeminent interpreter of the American West. But which West? The American frontier had been the backdrop for dramatic changes; economically, socially, environmentally and in the imagination. By the end of Cody’s career, crowds were coming to

Buffalo Bill’s

Wild West

in automobiles, he sometimes featured “aeroplane” flyovers, and he was investing in mineral rights in western states. Deadwood was featured prominently in his show but not for its stable businesses and settled family life.

As the Buffalo Bill exhibit on the main floor shows, Cody’s America was a world of unspoiled natural abundance in which heroic actions by individuals made a difference. His interpretation still prevails.

![ENC 1102 Hybrid Day 24‹Parts of an Annotated Bibliography [M 4-9]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006813293_1-f9df0b3a4fca2bb83cd912cb9db27c26-300x300.png)