new mexico archeological council 2006 fall conference

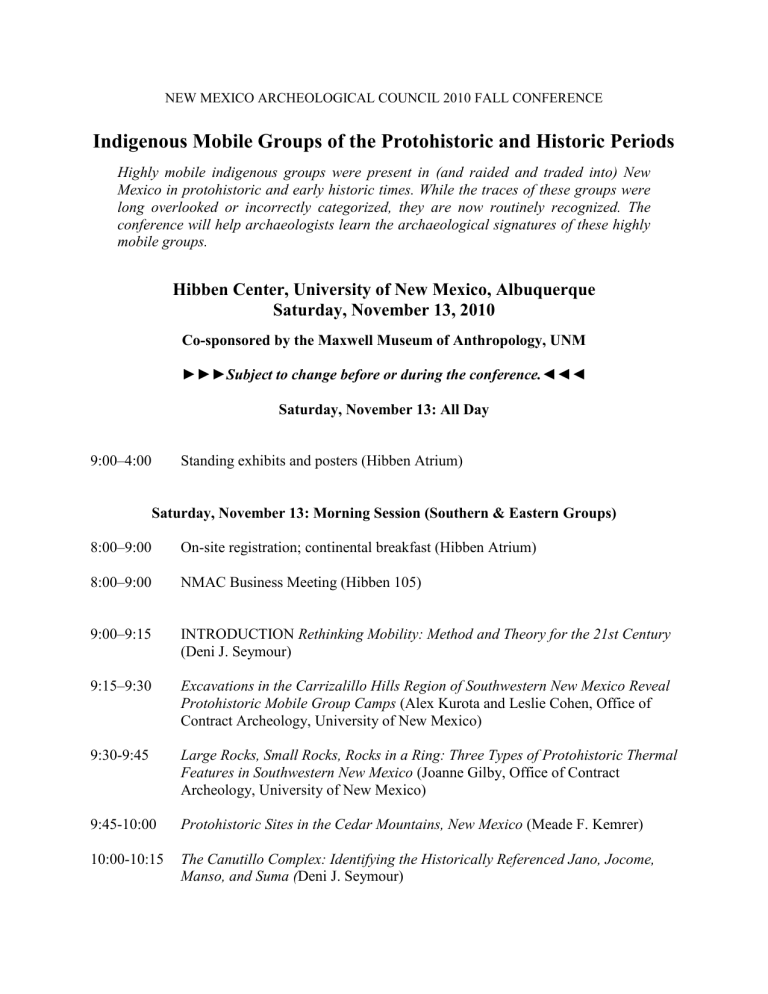

NEW MEXICO ARCHEOLOGICAL COUNCIL 2010 FALL CONFERENCE

Indigenous Mobile Groups of the Protohistoric and Historic Periods

Highly mobile indigenous groups were present in (and raided and traded into) New

Mexico in protohistoric and early historic times. While the traces of these groups were long overlooked or incorrectly categorized, they are now routinely recognized. The conference will help archaeologists learn the archaeological signatures of these highly mobile groups.

Hibben Center, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque

Saturday, November 13, 2010

Co-sponsored by the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, UNM

►►►Subject to change before or during the conference.◄◄◄

Saturday, November 13: All Day

9:00–4:00 Standing exhibits and posters (Hibben Atrium)

Saturday, November 13: Morning Session (Southern & Eastern Groups)

8:00–9:00 On-site registration; continental breakfast (Hibben Atrium)

8:00–9:00 NMAC Business Meeting (Hibben 105)

9:00–9:15 INTRODUCTION Rethinking Mobility: Method and Theory for the 21st Century

(Deni J. Seymour)

9:15–9:30 Excavations in the Carrizalillo Hills Region of Southwestern New Mexico Reveal

Protohistoric Mobile Group Camps (Alex Kurota and Leslie Cohen, Office of

Contract Archeology, University of New Mexico)

9:30-9:45 Large Rocks, Small Rocks, Rocks in a Ring: Three Types of Protohistoric Thermal

Features in Southwestern New Mexico (Joanne Gilby, Office of Contract

Archeology, University of New Mexico)

9:45-10:00 Protohistoric Sites in the Cedar Mountains, New Mexico (Meade F. Kemrer)

10:00-10:15 The Canutillo Complex: Identifying the Historically Referenced Jano, Jocome,

Manso, and Suma ( Deni J. Seymour)

NMAC Fall Conference, Nov. 13, 2010, Page 2

_____________________________________________________________________________

10:15-10:30 Discussion

10:30–10:50 Break; continuation of continental breakfast.

10:50–11:00 Session Statement

11:00–11:15 Plains Apache Diaspora: Implications for Archaeo-ethnicity (Jeffery R. Hanson,

Statistical Research)

11:15-11:30 Identification of Apache Iconography at Southern New Mexico and West Texas

Rock Art Sites (LeRoy Unglaub)

11:30–11:45 The Ancestral Apache Signature in the Southern Southwest (Deni J. Seymour)

11:45-12:00 Gilmore and Larmore; paper title forthcoming

12:00-12:15 Hughes- Tierra Blanca paper title forthcoming

12:00-12:15 Discussion

12:15–1:30 Break for lunch.

A Pueblo oven bread demonstration and sale of Indian tacos, posole, fry bread, oven bread, etc. will take place in the Maxwell Museum courtyard to coincide with the conference.

Saturday, November 13: Afternoon Session (Northern Groups and the Ute-Navajo

Controversy)

1:30-1:35 Session Statement

1:35-1:50 Peter Pillis, paper title forthcoming

1:50-2:05 Needzii': Diné Game Traps on the Colorado Plateau (Jim Copeland, Bureau of

Land Management)

2:05-2:20 Squeezing Blood from Stone Flaking Debris: Using Debitage as a Cultural and

Chronological Marker (Matthew Bandy, SWCA Environmental Consultants)

2:20-1:30 Questions and Introductory Comment—The Ute and Navajo Controversy (Deni)

1:30–1:45 The Colorado Wickiup Project (Curtis Martin, Dominquez Archaeological

Research Group)

1:45–2:00

The Old Wood Calibration Project and Colorado’s Missing Record of Ute

Prehistory (Steven G. Baker, Centuries Research; Jeffrey S. Dean and Ronald H.

NMAC Fall Conference, Nov. 13, 2010, Page 3

_____________________________________________________________________________

Towner, Laboratory of Tree Ring Research)

2:05–2:20 Site 42UN5406: A Numic and Ancestral Pueblo Ceramic Assemblage in the

Uintah Basin, Uintah County, Utah (

Christopher James (“CJ”) Truesdale)

James A. Truesdale, David V. Hill, and

2:20–2:45 Break; with snack

2:45-3:00 The Archaeological Difference between Ute and Navajo (David Brugge)

3:00–3:15 Ute versus Navajo for the Dinetah (Curtis Schafsmaa)?

3:15-3:30 Discussion, Additional questions and comments

NOTE: certificates of attendance for the Saturday symposium will be handed out at the end of the day, not before . Partial attendance does not count.

ABSTRACTS

In alphabetical order, by presenter or senior presenter

Steven G. Baker (Centuries Research); Jeffrey S. Dean and Ronald H. Towner (Laboratory of

Tree Ring Research, University of Arizona)

The Old Wood Calibration Project and Colorado’s Missing Record of Ute Prehistory

“The Old Wood Calibration Project” (OWCP) has been a collaborative effort between Centuries

Research, Inc. and the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research at the University of Arizona. The project was initiated in 2004 and has been investigating a suspected “old wood effect” in the radiocarbon and tree ring dating of hearth fuel woods from archaeological sites in western

Colorado. The OWCP has demonstrated that 1000+ year-old pieces of dead wood suitable for burning are present on the current landscape and that elements more than 600 years old are relatively abundant. It has also empirically demonstrated that the probability is high (virtually

100 percent) that radiocarbon or tree ring dates from pinion or juniper charcoal from hearths or other thermal features will be significantly older than the human acts of building and maintaining a fire with such pieces of dead wood. These ages will commonly be significantly earlier than the ranges indicated by even the two sigma confidence levels in radiocarbon dating. Such confidence levels alone should thus no longer be relied upon for approximating the dates of occupations. In the project’s three study areas of Colorado’s western slope three different minimal mean-age

NMAC Fall Conference, Nov. 13, 2010, Page 4

_____________________________________________________________________________ correction factors were determined. These range from 482 years on the Douglas Creek Arch to

219 years further south in the Montrose area.

Regional radiocarbon dates based on hearth fuel woods can accordingly no longer be accepted at standard confidence levels but must be adjusted by adding correction factors. The OWCP suggests that the dating chronologies currently in use relative to the occupations by Colorado’s

Ute Peoples significantly overstate their age. Even when minimal correction factors are applied to the radiocarbon dates for bona fide Ute sites, the archaeological record for the Ute presence in western Colorado moves forward in time to the very late prehistoric or early historic contexts at least. Ute sites from this time frame are both obvious and not uncommon in western Colorado.

This interpretation relating to the late time frame for the Ute occupation is supported by both linguistic and rock art data as well as negative data stemming from a currently perceived near total absence of Ute sites at demonstrable prehistoric time depth. These findings appear to explain why, despite our gains in learning to identify the Ute archaeological culture, evidence of such an older Ute occupation has to date proven to be so elusive. Beyond Colorado the OWCP has major implications for the prehistoric chronometric record of the Desert West. Work is now underway to further test these findings and to carry the research into additional areas.

Matthew Bandy (SWCA Environmental Consultants)

Squeezing Blood from Stone Flaking Debris: Using Debitage as a Cultural and Chronological

Marker

The flake scatter is one of the most common types of archaeological site routinely encountered in archaeological inventories. However, the information potential of these sites is severely limited by our inability to place them within a chronological context. Without an idea of when they might date to, it is difficult to assess changes in human behavior on a landscape scale. The problem is particularly acute for mobile populations that typically deposit few chronologically diagnostic artifacts. This paper presents an approach for using lithic debitage as a chronological indicator. The approach is illustrated with an example from northwestern Colorado.

Jim Copeland (Bureau of Land Management)

Needzii': Diné Game Traps on the Colorado Plateau

Game traps recorded by Navajo Lands Claim archaeologists across the Colorado Plateau and more recently by the BLM in the San Juan Basin offers some insight to the level of cooperation and effort required to conduct drive hunts. Understanding the location and placement of these features may help in the interpretation of other sites on the landscape. The results of some field surveys associated with game traps are also presented.

NMAC Fall Conference, Nov. 13, 2010, Page 5

_____________________________________________________________________________

Joanne Gilby (Office of Contract Archeology, University of New Mexico)

Large Rocks, Small Rocks, Rocks in a Ring: Three Types of Protohistoric Thermal Features in

Southwestern New Mexico

During OCA’s Border Fence Project excavations, groups of thermal features in the Carrizalillo

Hills region provided twelve surprising radio-carbon assays, all dating to the Protohistoric/Early

Historic era. These sites are therefore interpreted as being of Apache or other protohistoric group affinity. Analysis of the morphology and the macrobotanical/faunal remains from numerous thermal features aided in deciphering their discrete physical attributes, assessing their function, and ultimately placing them into emerging typological categories. Three distinctive thermal feature types are presented here to offer a beginning typology of protohistoric thermal features for southwestern New Mexico. This typology leads to the conclusion that each type is a specialized construction, differently using rocks and other attributes for temperature and heat duration control.

Jeffery R. Hanson (Statistical Research, Inc.)

Plains Apache Diaspora: Implications for Archaeo-ethnicity

Four of the more significant challenges of assigning tribal identification to archaeological sites and complexes are migration, mobility, ethnogenesis, and cultural change. Each of these factors has implications for the nature and content of archaeological assemblages. These challenges are illustrated by the Plains Apache diaspora, in which several groups of Apaches from a common ancestral area experienced significant territorial shifts and cultural changes which in some cases severed their connection to their archaeological past.

Meade F. Kemrer

Protohistoric Sites in the Cedar Mountains, New Mexico

Surveys in the Cedar Mountains identified protohistoric and historic Native American sites. This paper describes the radiocarbon dates, settlement characteristics, and artifacts. These sites conform to with the nomadic occupations Seymour described and found in the southern

American Southwest.

NMAC Fall Conference, Nov. 13, 2010, Page 6

_____________________________________________________________________________

Alex Kurota and Leslie Cohen (Office of Contract Archeology, University of New Mexico)

Excavations in the Carrizalillo Hills Region of Southwestern New Mexico Reveal

Protohistoric Mobile Group Camps

The Office of Contract Archeology recently excavated four Protohistoric period sites in the

Carrizalillo Hills region of southwestern New Mexico. The research conducted under the Border

Fence Project revealed new information on these mobile group camps from the southern

Southwest. Twelve radiocarbon and two thermoluminescence dates place the four sites and all excavated features consistently into the mid-15th to the late 19th century. This research uncovers new evidence for these mobile groups’ subsistence practices, lithic procurement, lithic tool manufacture and recycling, seasonality of use, and their movement throughout the landscape.

Curtis Martin (Dominquez Archaeological Research Group)

The Colorado Wickiup Project

The ongoing Colorado Wickiup Project has documented 366 aboriginal wooden features

(wickiups, tree platforms, etc.) on 58 sites in western Colorado. The findings have provided new understanding regarding the Protohistoric and Early Historic Northern Ute and their continued occupation of traditional, off-reservation, homelands after their removal to reservations.

Dendrochronological dates from metal ax-cut feature elements range from A.D. 1815 to

1915/1916, with over half of the dates indicating occupation during post-“removal” times (after

1881). Two of the sites were occupied after 1900. Two resources have revealed relatively unique site types in the archaeological record of western Colorado. At one, the Ute Hunters’ Camp

(5RB563), canvas wall tents provided shelter for the occupants occupied with meat and hide processing, bullet reloading, and, possibly, leather working. Another, the Black Canyon Ramada

(5DT222), includes the partially collapsed remains of a Protohistoric flat-roofed sunshade. Based on our findings, this author proposes that Phase V of Baker’s Model of Ute Culture History be divided into two sub-phases. The proposed Phase V-A, or “Ungacochoop Phase,” would embody post-1900 Early Historic Era sites.

Deni J. Seymour

The Canutillo Complex: Identifying the Historically Referenced Jano, Jocome, Manso, and Suma

It has been ten years since the signature of the Canutillo complex was defined by the speaker as a distinctive archaeological manifestation. Since then similar sites have been found in surrounding areas occupied by these groups and other archaeologists have replicated the findings. This work has extended the geographic distribution of known sites and provided an even stronger suite of dates and feature types to define this non-Apache protohistoric archaeological complex.

Deni J. Seymour

NMAC Fall Conference, Nov. 13, 2010, Page 7

_____________________________________________________________________________

The Ancestral Apache Signature in the Southern Southwest

Apache residential and roasting sites are now recognized with ever-increasing frequency, despite the long-standing maxim that Apache sites are difficult to identify and therefore are rarely found.

Why is it that archaeologists now feel confident in assigning this affiliation? What evidence is used to distinguish this group archaeologically from contemporaneous ones? In the absence of

European artifacts how can Apache sites be isolated? What is the range of known feature types and how do they differ from other Apachean groups? How has the documentary record been misleading us and how can a change in conception and methodologies help archaeologists in identification?

Deni J. Seymour

INTRODUCTION Rethinking Mobility: Method and Theory for the 21st Century

Existing conceptions that distinguish limited-activity sites and residential sites are detrimental for understanding material and spatial evidence related to mobile groups. Similarly, the Binforddevised models of site structure which are based on ethnoarchaeologically derived information are inappropriate for Southwestern open sites occupied for the short term. Despite the prevalence of these models, archeological evidence indicates that sites are much more dispersed, without a residential-core focus and that activities are not focused on hearths. Worldwide evidence of this pattern provides a cross-cultural basis for assessing its significance for site interpretation and boundary definition.

James A. Truesdale, David V. Hill, and Christopher James (“CJ”) Truesdale

Site 42UN5406: A Numic and Ancestral Pueblo Ceramic Assemblage in the Uintah Basin,

Uintah County, Utah

The dating of the arrival of Numic-speaking peoples into the Southwest is currently controversial. Clear associations of material culture that can be associated with Numic occupations dating prior to the eighteenth century are rare. The ceramic and lithic assemblage from 43UN5406 indicates the presence of Numic-speakers in northeastern Utah and the Greater

Southwest by the early fourteenth century. Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) dating for a finger-nail impressed sherd supports the fourteenth century occupation of the site.

LeRoy Unglaub

Identification of Apache Iconography at Southern New Mexico and West Texas Rock Art Sites

Southern New Mexico and West Texas has a number of rock art styles to include multiple archaic styles, the Jornada-Mogollon style which is the principal rock art style in this region,

NMAC Fall Conference, Nov. 13, 2010, Page 8

_____________________________________________________________________________

Apache style, and possibly others. Some Apache iconography is relatively easy to identify but becomes more difficult especially at sites with multiple rock art styles. This paper will discuss and illustrate the methods and criteria used to identify Apache iconography at a number of rock art sites in Southern New Mexico and West Texas.