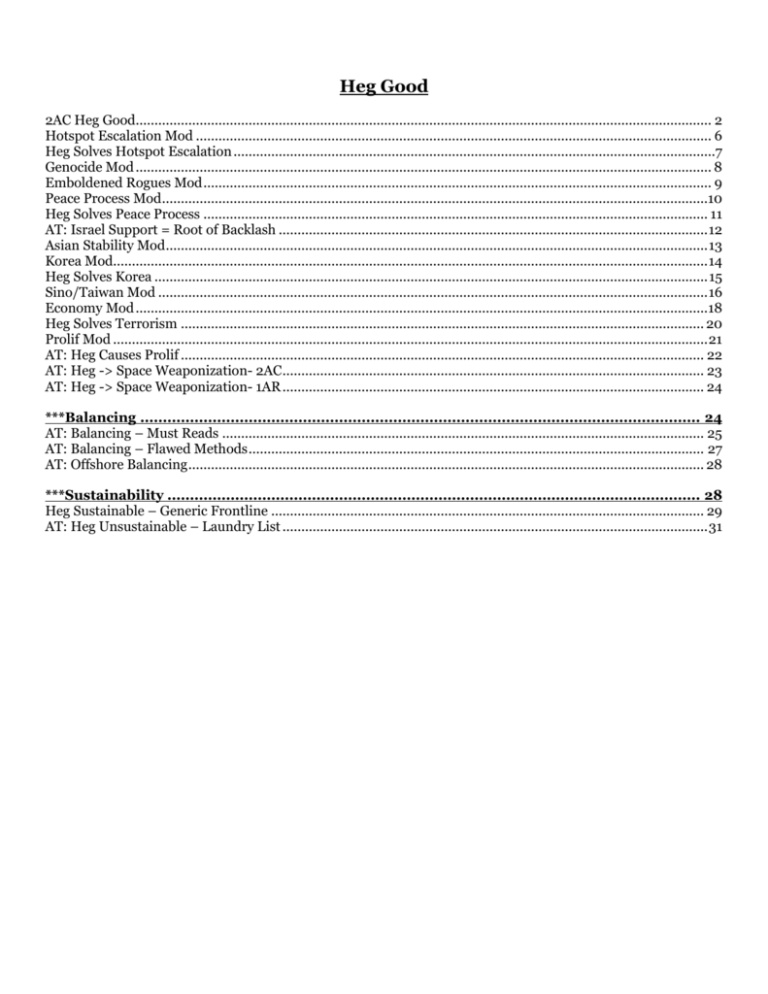

2AC Heg Good - Open Evidence Archive

advertisement