Therapeutic MDMA (Ecstasy) & The Federal Government

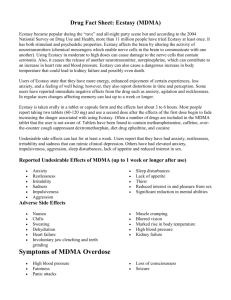

advertisement