La Esperanza - EnergyAccess

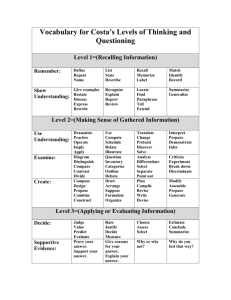

advertisement

La Esperanza Began: In 1999, CISA was established as a Honduran corporation by two small electric sector companies (Honduran enterprise SIMET and Canadian enterprise UEE), for the explicit purpose of owning and operating small hydro generation facilities in Honduras and other Central American countries. CISA selected La Esperanza as its first project for development in Honduras. What: La Esperanza is a 13.5 MW run-of-river hydro facility located in Intibuca, in western Honduras. It was built in 3 stages (stages 1a, 1b and 2) over several years using each stage to demonstrate success and generate positive cash flow. The Energy Need: From the outset, CISA sought to address both local and national needs, while generating a business opportunity by rehabilitating an old hydroelectric plant. The site, known as “La Pozona”, is located in La Esperanza’s communal lands and had been abandoned in 1969 when La Esperanza’s power supply was integrated into the national grid. The quality and reliability of power supply in the 10,000 inhabitant town was poor due to the long distance to the substation from which ENEE (the national utility) was sourcing it. CISA negotiated with the Municipality the land rights to the hydroelectric site in exchange for undertaking several measures benefitting the community; these included: repairing the access roads to the powerhouse, watershed forest protection, direct and indirect job creation, and balancing the electric system by injecting power locally into the grid, thus increasing the quality of electric services to La Esperanza. Additionally, CISA committed to contribute resources for the extension of the grid for two additional towns Santa Anita and San Fernando (750 inhabitants), which lacked access to electricity. At the national level, Honduras was facing a strong energy supply crisis. Following extreme shortages in 1993, the country had increasingly become dependent on fossil-fuel generation that could be brought online quickly. This in turn drove up the cost of electricity for the utilities and end users. By 2000 the country was using emergency plants for generation. E+Co Investment: $1,250,000 in two loans and one equity investment, starting in 2003. Business Development: Business planning assistance provided by E+Co in 2003 as well as help assessing and quantifying carbon offset potential, preparing the project to become the first registered provider of Emission Reduction Credits under the Clean Development Mechanism. Now (2008): La Esperanza has now completed all major generation projects and is continuing to operate profitably, paying down its debt obligations and performing routine maintenance. Outcomes/Impacts: La Esperanza now provides clean energy to the national distribution company, ENEE. ENEE distributes the energy to its country-wide customer base. The energy provided by La Esperanza is sufficient to supply over 12,000 customers. The quality and reliability of electric service has been significantly improved for the 10,000 residents of the La Esperanza area. Additionally, 150 households in the neighboring villages of Santa Anita and San Fernando are now connected to the grid though the contribution of La Esperanza and other supporting organizations (including ENEE and the World Bank). 75 jobs have been created; over 200,000 trees have been planted; and a micro-lending program was started for CISA’s workers. In 2005, La Esperanza became one of the first two projects worldwide to receive Emission Reduction Credits (ERCs) issued by the Clean Development Mechanism. La Esperanza’s carbon offsets were estimated at approximately 37,000 Tons CO2e/year. Lessons learned: 1) Integrate local needs realistically 2) Start small 3) Establish alliances 1) Integrate local needs realistically: CISA’s developers understood all along that the neighboring communities would be an important stakeholder throughout the life of the project. They strove to develop a project in a way that brought added value to the quality of life of the surrounding communities. More importantly, they sought the input of the members of the communities about what their specific needs were and the ways in which the project could work with the community to address specific needs. This is often a complex issue, because developers often fear that communities will make unrealistic demands in exchange for supporting the project. These demands are often rooted in their perception that the project is a “cash cow”, a view that overlooks the heavy burden of debt service in the initial years of a project’s cashflow, particularly when the developer is a small enterprise. This situation sometimes leads developers to try to avoid as much as possible addressing communities’ perceptions of their local needs. Instead, developers often make the argument that communities should see the project itself as a local benefit, because it will generate clean energy needed by the country, provide local employment (although the majority of the jobs are only for the construction period) and yield other local benefits as a result of the construction process, such as the improvement of some access roads. CISA’s approach to working with communities seems to have achieved a reasonable balance between addressing community needs and preventing the emergence of excessive demands. From the outset, it identified how the project’s own activities could provide benefits to the surrounding community: through employment, improved access roads, reforestation and especially by improving the quality of electricity supply to the town of La Esperanza. However, in its meetings with the surrounding communities it also listened to what the local stakeholders perceived to be their own needs, and examined ways in which the project could assist in meeting those needs. This latter case entailed additional efforts that went beyond the normal activities of constructing the power plant and maintaining the infrastructure and the water resource. CISA was willing to make a contribution on this regard, but it also stressed that the communities themselves, and the government agencies in charge of providing these services, should not be relieved of their own responsibilities in relation to the provision of these services. The need that was stressed by surrounding communities was the electrification of the smaller towns surrounding La Esperanza, which were unable to afford on their own the cost that the power distribution company (ENEE) would have charged them for extending the grid. CISA supported the communities in their request of the grid extension and made an in-kind contribution and a financial contribution of at least $12,000 that allowed the electrification of 150 households in the neighboring communities of Santa Anita and San Fernando. CISA worked in collaboration with the communities or the local power distribution company (ENEE), thus ensuring that these other stakeholders recognized their own responsibilities in pursuing the electrification of these villages. Hence, ENEE also invested its own resources in the grid extension, and the community provided in-kind work and sought loans to pay for the internal electric installation of their own homes. CISA was also instrumental in obtaining additional funds from the World Bank to support this electrification initiative. 2) Start small: From the outset in 1999, it was envisioned that La Esperanza Hydroelectric facility would be a 13.5 MW project. However, the project developers decided to start small by using an existing WWII-era powerhouse and installing only 485 kW of capacity (stage 1a). Later, once this stage was operational, the project was expanded to a total of 1 MW (stage 1b), also employing that same powerhouse. Though money could no doubt have been saved by developing both stages simultaneously, the phasing allowed the project to begin sooner since smaller capital outlays were needed. Then, having tested the waters and proven that the project was indeed viable, it was easier to search for and acquire subsequent loans. La Esperanza Installed Capacity by Year 16000 14000 Capacity (kW) 12000 10000 8000 6000 4000 2000 0 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 Year Financing for La Esperanza Level of Investment (K USD) 9000 8000 7000 E+Co Finance (K USD) 3rd Party Finance (K USD) 6000 5000 4000 3000 2000 1000 0 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 Year Stages 1a and 1b, were more than demonstrative projects; they helped control water flow for the eventual, much larger, stage 2 portion of the project. Stage 2 necessitated the construction of a new powerhouse and dam. It became operational in 2006, the same year that CISA signed a 15-year power purchase agreement with the Honduran national electrical utility. This is three years after the stage 1a came on line and six years after CISA was incorporated. Comparing this timeline with other similar type projects in the region, it is fair to say that three years of construction from start to finish is much longer than most other developers anticipate, yet six years for total project completion is actually very respectable. 3) Establish collaborative relationships CISA recognized that becoming a trailblazer in a new field, such as small hydroelectric development, would be a complex undertaking with multiple issues to address. The project’s long-term success would be dependent on good communication and strong collaborative relationships with a number of stakeholders, including the energy consumer (ENEE), the environmental regulator (SERNA), funding and investment sources, carbon trade agents, surrounding communities, municipal governments, other small-scale electricity developers, skilled local workers and experts in a number of fields. The project developers devoted considerable attention to building good working relationships and strong communication with all these stakeholders. CISA became very engaged in the Honduran Association of Small Private Renewable Energy Producers (AHPPER) and worked with decision-makers to promote legislation that established a friendlier environment for renewable energy. La Esperanza’s sponsors also developed a collaborative working relationship with the communities surrounding La Esperanza, with ENEE and with the World Bank’s Community Development Carbon Fund in order to promote the electrification of the nearby villages of Santa Anita and San Fernando. The project also worked closely with the Honduran Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources (SERNA), with several specialized organizations, and with the World Bank in the complex process of certification and trade for its carbon emission reductions; it was due to this positive collaboration and to the project’s focus on incorporating social benefits that La Esperanza became, together with another Honduran project, the world’s first recipient of Emission Reduction Credits under the Clean Development Mechanisms. Furthermore, the World Bank, through its Community Development Carbon Fund, was willing to provide an upfront partial payment of its CERs, in order to support the implementation of community benefits. Thumbnail Analysis: The Policy-Technology-Enterprise balanced approach: Policy: Sought to overcome high dependency on fossil fuels and reduce GHG emissions. It included incentives for small hydro, a framework for selling power to the national utility and bundling of Carbon credits for the CDM. Technology: Hydro was well suited to the site. By rehabilitating an abandoned site the project was able to move in gradual stages. New site provided stability to the system, an immediate benefit to local communities. Enterprise: Able to build strong collaborative relationships. Recognized the importance of partnering with communities to address local needs. Willing to demonstrate a track record of technical and managerial competency by developing the project in successive stages. The Enterprise-Customer connection: e: Sponsors competent in electric d: Rising national power system rates infrastructure and in building national and local stakeholder relationships & overdependence on fossil fuel emergency plants. Unreliable or unavailable power supply in surrounding towns. t: Small hydro in 3 phases k: State authorities needed a frame- (485 kW, 1 MW, 13.5 MW) well suited to the site and contributing to solve national and local energy needs Se: Assistance in business plan work for purchasing power from independent producers. Organizational support to unelectrified communities. E C Sc: Support to unelectrified development and in quantifying and marketing carbon offsets communities in completing the procedures for acquiring credit for internal household electric installation. Fe: E+Co: 2 loans & 1Equity Inv. Fc: Finance to support unelectrified ($1.25 M); CABEI: $6.0 M Loan; FinnFund: $1.9 M Subord Loan; Hon banks $8.5 M (substitutes CABEI). communities with the cost of grid extension. e: Entrepreneur t: Technology Se: Services to the enterprise Fe: Finance for the enterprise E: Enterprise C: Customer d: Demand k: Knowledge Sc: Services to the customer Fc: Finance for the customer