3-484

advertisement

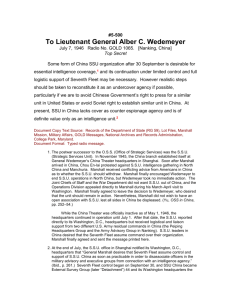

#3-484 Editorial Note on the Conference at Casablanca January 13–24, 1943 Swift Allied victory in North Africa following the TORCH landings had failed to occur for many reasons, including overextended supply lines, rapid reinforcement by the Germans and Italians of the positions they had seized in northern Tunisia, and adverse weather conditions. Nevertheless, Allied leaders were confident of a successful outcome, despite temporary delays. The strategic question facing Roosevelt, Churchill, and their military advisers at the end of 1942 was what offensive action to undertake after the conquest of North Africa. Prime Minister Churchill and the British Chiefs of Staff had concluded, after considerable debate among themselves during the autumn of 1942, that the Allies did not have the requisite shipping, troops, or air forces to sustain a crossChannel invasion until German military power had been further worn down, which very likely would not be in time for a landing in 1943. Consequently, they decided that for the war's next stage the Allies should concentrate all available forces against Italy in the hope of forcing it to sue for peace, thereby obliging the Germans to assume Italian commitments in the Balkans, Greece, and various Mediterranean islands, further straining Germany's overtaxed resources. As 1942 ended, the British Chiefs of Staff had not decided whether the next Allied offensive should be aimed at Sardinia (Operation BRIMSTONE) or Sicily (Operation HUSKY). (Michael Howard, Grand Strategy, volume 4, August 1942September 1943, a volume in the History of the Second World War [London: HMSO, 1972], pp. 225–36.) President Roosevelt was sympathetic to British strategic opinions, but his military planners, while not entirely unified, generally were not. Marshall believed that the North African operation had been a strategic detour and that its completion meant that fresh impetus should be given to BOLERO—i.e., the accumulation of troops and materiel in Britain preparatory to launching ROUNDUP, an assault landing in France, probably on the Brittany peninsula. By December 21, Roosevelt and Churchill had arranged a conference for midJanuary 1943, this time in Casablanca, Morocco. While this gave United States military planners more time to prepare than they had been allowed for the three previous heads-of-state meetings, they were, the army's official history notes, just beginning to appreciate how well prepared they needed to be in order to meet the British on equal terms in the discussions. Moreover, President Roosevelt limited his chiefs of staff to a handful of conference assistants. (Ray S. Cline, Washington Command Post: The Operations Division, a volume in the United States Army in World War II [Washington: GPO, 1951], pp. 214–15.) The final preconference meeting between the Joint Chiefs of Staff and their commander in chief took place in the White House on the afternoon of January 7, two days before the chiefs were scheduled to leave. Roosevelt asked Marshall if the military were united in agreement to advocate a cross-Channel operation. Marshall replied that they were not, especially the planning staff. The minutes record the chief of staff as saying that he "regarded an operation in the north more favorably than one in the Mediterranean but the question was still an open one.” Further, of the two most likely Mediterranean operations—Sardinia and Sicily—the latter, while more difficult, was more desirable. "He said that he personally favored an operation against the Brest peninsula. The losses there will be in troops, but he said that, to state it cruelly, we could replace troops whereas a heavy loss in shipping, which would result from the BRIMSTONE Operation, might completely destroy any opportunity for successful operations against the enemy in the near future.” While ROUNDUP would also entail losses, Marshall said, there would be "no narrow straits on our lines of communications, and we could operate with fighter protection from the United Kingdom.” When the North African operation was completed, the president noted, the Allies would have a half million surplus troops there; where were they to be employed? Marshall "pointed out that we were already training divisions for the BRIMSTONE Operation in case a decision was made to mount it." (Foreign Relations, Conferences at Washington and Casablanca, pp. 509–10, 512. The minutes of the January 7 meeting and of all the formal J.C.S. and C.C.S. meetings at the Casablanca Conference are printed in this volume. The army history of the conference is Maurice Matloff, Strategic Planning for Coalition Warfare, 1943–1944, a volume in the United States Army in World War II [Washington: GPO, 1959], pp. 18–42.) Marshall, King, Arnold, and their party (except Admiral Leahy, who was traveling with the president's party but had to return home because of illness) left Washington on January 9 in two C-54s, reaching Casablanca—via Puerto Rico, Brazil, and Gambia—on the morning of January 13. Marshall later described his journey to his sister; see Marshall to Singer, February 1, 1943, Papers of George Catlett Marshall, #3-494 [3: 526–27]. Albert C. Wedemeyer, then a brigadier general and the chief army planner, gave an account of the trip, the setting in Casablanca, and his opinions of the conference in Wedemeyer Reports! (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1958), pp. 169–92. The first of twenty formal meetings in which Marshall participated—fifteen of them with the Combined Chiefs of Staff—began on the morning of January 14 in the Anfa Hotel just outside Casablanca. During the first four days, the conferees discussed the broad outlines of strategy. Both heads of state and their military chiefs reaffirmed during the conference that Germany was the primary and Japan the secondary enemy; likewise, all were agreed that the enemy must not be allowed time to recuperate from recent Allied blows or to reinforce their defenses. The differences among them arose over what this meant operationally. Marshall told the British that the Allies should double the proportion of their total resources allocated to the Pacific theater (which included China and Burma). The Japanese had repeatedly demonstrated their military capabilities, and they must not be permitted to regain the initiative or to create a stronger defensive network; thus the Allies could not rely on a static defense in the Pacific but had to continue an aggressive offense. Pacific operations were extremely expensive in terms of merchant shipping and fighting vessels. To reduce this burden, Japan and its shipping had to be attacked more vigorously; an important way to do this was by increasing Allied air power in China. To support this, more supplies had to be sent to China; and to accomplish this, Burma had to be recaptured (Operation ANAKIM) and the supply route reestablished. In addition, given the conditions of the naval war there, the Pacific struggle was "fraught with the possibility of a sudden reverse and the consequent loss of [Allied] sea power.” Execution of Operation TORCH had once been threatened by Pacific difficulties, Marshall asserted; if ANAKIM were not undertaken, "a situation might arise in the Pacific at any time that would necessitate the United States regretfully withdrawing from the commitments in the European theater. . . . The United States could not stand for another Bataan." (Foreign Relations, Conferences at Washington and Casablanca, p. 603.) The British military chiefs feared that United States efforts in the Pacific would drain resources from the battle in Europe. Germany, which British opinion held was already showing signs of military weakness, was still too strong in northern France, and had too great an ability to reinforce its position there, for the Allies to risk a cross-Channel invasion soon. Moreover, to attempt ROUNDUP would necessitate a massive shifting of Allied troops from North Africa and the United States to Britain, and the shipping shortage and consequent time required to accomplish this meant that the Germans would have nearly six months to recover from their Russian and North African losses. If an operation were launched in the Mediterranean, the British chiefs argued, shipping demands would be reduced, a major operation could be launched during the late spring or summer of 1943, there was a good chance of eliminating Italy from the war, and Germany would have difficulty reinforcing its positions in southern Europe. Every diversion from the cross-Channel operation served as a "suction pump" which drew in more and more Allied resources, Marshall declared at the January 16 C.C.S. meeting; but he did admit that "operations against Sicily appeared to be advantageous" given the number of Allied troops that would remain in North Africa after victory there. That evening the J.C.S. met with President Roosevelt. It was clear that the British would not cooperate in a crossChannel invasion before 1944 unless the Germans showed signs of weakening, Marshall stated. The joint chiefs had concluded, therefore, that Operation HUSKY, the invasion of Sicily, should be undertaken. The British had not yet been informed of this, Marshall noted; he hoped first to obtain their agreement on Pacific strategy. (Ibid., pp. 583, 597.) Compromise with the British concerning Pacific operations proved to be more difficult than Marshall had anticipated. The British chiefs were reluctant to commit themselves to ANAKIM and to approve United States plans to seize the Gilbert, Marshall, and Caroline islands, seeing these as deviations from the Germany-first strategy. The minutes record Marshall as insisting that he did "not propose doing nothing in the Mediterranean or in France.” But he was "opposed to immobilizing a large force in the United Kingdom awaiting an uncertain prospect, when they might be better engaged in offensive operations which are possible. . . . He was most anxious not to become committed to interminable operations in the Mediterranean.” Moreover, the United States could not continue conducting Pacific operations on a "shoe string.” At the end of the morning C.C.S. meeting on January 18, Marshall proposed a compromise in which U.S. Pacific operations would be conducted without asking for additional forces but "with the resources available in the theater.” The British accepted this, with minor modifications, on January 19. Three days later the military leaders had agreed that HUSKY should be launched in late July. Both Roosevelt and Churchill wished the landing to take place earlier, but specific plans were left to Eisenhower and his staff. (Ibid., pp. 618–19, 622, 637, 684.) Once the key strategic decisions were made, the C.C.S. filled in details and worked through a succession of papers (most submitted by British planners) during the final six days of meetings. No one doubted, for example, that "a first charge on the resources of the United Nations" must be the war against German U-boats, which at this time was not being won. (Ibid., p. 774.) Somewhat related to this was the conduct of the Combined Bomber Offensive (Operation POINTBLANK) against the Germans. Marshall agreed that the British would exercise overall strategic direction, but the U.S. Army Air Forces would maintain control over the methods it would use (e.g., daylight bombing). (Ibid., pp. 781– 82.) Further, no one doubted that supplies should continue to flow to the Soviet Union. The chief concern was the cost in Allied ships of the dangerous northern route to Murmansk; Marshall "said that he does not believe it necessary to take excessive punishment in running these convoys simply to keep Mr. Stalin placated." (Ibid., pp. 632–33.) Bringing Turkey into the war on the Allied side was an agreed goal, implementation of which was left to the British. (Ibid., pp. 649–52, 659–60.) Nor was the question of rearming the French forces available in North Africa—estimated to be 250,000 men—a divisive issue. Although the service chiefs would not discuss the details of the amount or timing of such aid, they applauded General Giraud's statement to them of French confidence and determination. (Ibid., pp. 639, 652–55.) At the final press conference on January 24, President Roosevelt told reporters that the Allies would demand "unconditional surrender" of the Axis powers; this meant, he said, not the destruction of their peoples but "the destruction of the philosophies of those countries which are based on conquest and the subjugation of other people." (Ibid., p. 767.) Despite its military implications, the president had not discussed this announcement with his chiefs of staff, although he had used the phrase in passing at the preconference meeting on January 7. (Ibid., p. 506.) The British Chiefs of Staff were pleased with having accomplished most of their conference agenda. U.S. Navy and Army Air Forces leaders also had reason to feel that their roles and strategic views had been enhanced by the meetings. U.S. Army planners, however, especially Albert Wedemeyer, believed that superior British preparation and unity had defeated the United States by concentrating on the Mediterranean and placing preparations for the crossChannel invasion far down the priority list. One consequence of this attitude was that army planners would come to future conferences better prepared. (Howard, Grand Strategy, 4: 278; Wedemeyer, Wedemeyer Reports! pp. 191–92, 210–17. See Marshall Memorandum for General Wedemeyer, April 6, 1943, Papers of George Catlett Marshall, #3-594 [3: 634–35].) Recommended Citation: The Papers of George Catlett Marshall, ed. Larry I. Bland and Sharon Ritenour Stevens (Lexington, Va.: The George C. Marshall Foundation, 1981– ). Electronic version based on The Papers of George Catlett Marshall, vol. 3, “The Right Man for the Job,” December 7, 1941-May 31, 1943 (Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), pp. 513– 518.