bray_bio_sketch - The Institute for Advanced Technology in the

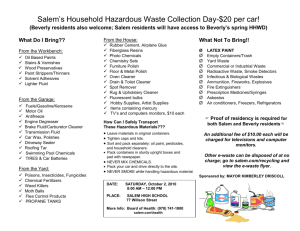

advertisement

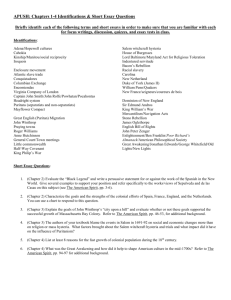

Brief bio sketch. After finishing the graduate program in History of Religions at the University of Chicago, I started out teaching and publishing at Princeton University in two different but related fields. The first was the field African traditional religions, in which I pursued an anthropological fieldwork approach. The second was the sub-discipline of comparative religions, in which I focused on issues in theory and method. In addition to doing periodic fieldwork in central Uganda and southwestern Nigeria, I wrote on issues involved in the study of myth and ritual among non-literate and pre-historic societies. I wrote a classroom textbook on African religions, which, after 20 years, is now in its second revised edition. At the University of Virginia I continued in the same mode, and published a monograph on the myth and ritual aspects of the ancient kingdom of Buganda. Then followed an edited collection of essays on issues in the contemporary study of comparative religions, in response to the critiques of postmodernism. An important turning point in the classroom was a UVA grant to create a new undergraduate course that utilized technology in the classroom. For this purpose I developed a new course on African traditional art, using a large collection of digital images of African art objects supplied by the Fowler Collection of African art at UCLA in collaboration with the Getty Museum. With these images, students in this class designed and created their own exhibitions of African art for presentation on the Web incorporating the results of classroom lectures and library research. This course has become one of the models at the University of Virginia for using digital technology in the classroom, transforming the classroom experience into a student oriented, collaborative learning, and project focused environment. In the course of teaching annual Senior Seminars in the Department of Religious Studies on various subjects that are chosen from outside the instructors’ usual course offerings, I selected the subject of the Salem witch trials for one of the semester classes. I wanted students to grapple with a range of interpretative approaches that have been applied to this subject -- the many psychological, theological sociological, and economic, interpretations. More importantly, I wanted students to grapple with the primary sources themselves, to learn about the social and religious context, to hear the “voices” of the people in the court records, like a field anthropologist, and to grasp how the witchcraft episode was experienced on the ground, so to speak, in the words of the participants. I also wanted students to learn good historical method, engage in critical thinking, and develop their own perspective. In 1999 I received a small grant to create an electronic edition of the out-of-print three volumes of court records, the Salem Witchcraft Papers, and put them online in searchable form. Next came the discovery of my own ancestors involvement (as defenders of Rebecca Nurse) which both spurred my interest and led me to take great care in imposing conventional interpretations on this complex subject. The Salem seminar was such a success that I wanted to place more primary source documents online and develop some digital tools for scholarly research. This led to participation in University of Virginia’s renowned Institute of Advanced Technology in the Humanities (IATH) and then to a large NEH grant to digitize more primary source material, to create interactive historical maps, and to join together with other scholars in the enormously complicated task of creating a new transcription of all the original 2 manuscript records. The result was the Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project. In 1999 the instructional and research potential of the Internet was just being discovered , and I in turn was discovering how the Salem Archive , as well as the digitized version of my African art class, was transforming my own teaching and research. The University of Virginia supported my classroom efforts by putting laptops in the hands of all my students in the Salem seminar, filling them with electronic texts, giving me a wireless classroom. This resulted in changing my seminar into a collaborative laboratory for digital history, in which students used a large number digital and library resources to write their own, original biographical profiles of important people involved in the Salem witch trials, the best of which I placed in the Salem Archive. In this setting, students were able to “become their own historians,” as one student put it, fully informed about current scholarly work and steeped in the original sources. Creating the Salem Archive has also opened up a wider collaborative world of scholarship to me, from 17th historical linguists, to historical geographers, to database programmers, and New England archivists and historians. My classroom is also no longer confined to the buildings and grounds of the University of Virginia. During the academic year, I respond to dozens of emails from both teachers and students using the Salem Archive, and from scholars who are using it in their research. Instead of presenting papers only to the annual meetings of the American Academy of Religion, I find myself giving papers to the American Historical Association, Social Science History Association, Geography conferences, Early American History meetings, American Anthropological, and digital scholarship conferences. As a result of the Salem Archive and Fellowship at IATH, my recent academic biography, then, has undergone significant transformation in both teaching and scholarship. But it has also remained consistently grounded in primary source work focused on small scale communities and the intersection of their theology and social life in historical perspective, both in my research and teaching.