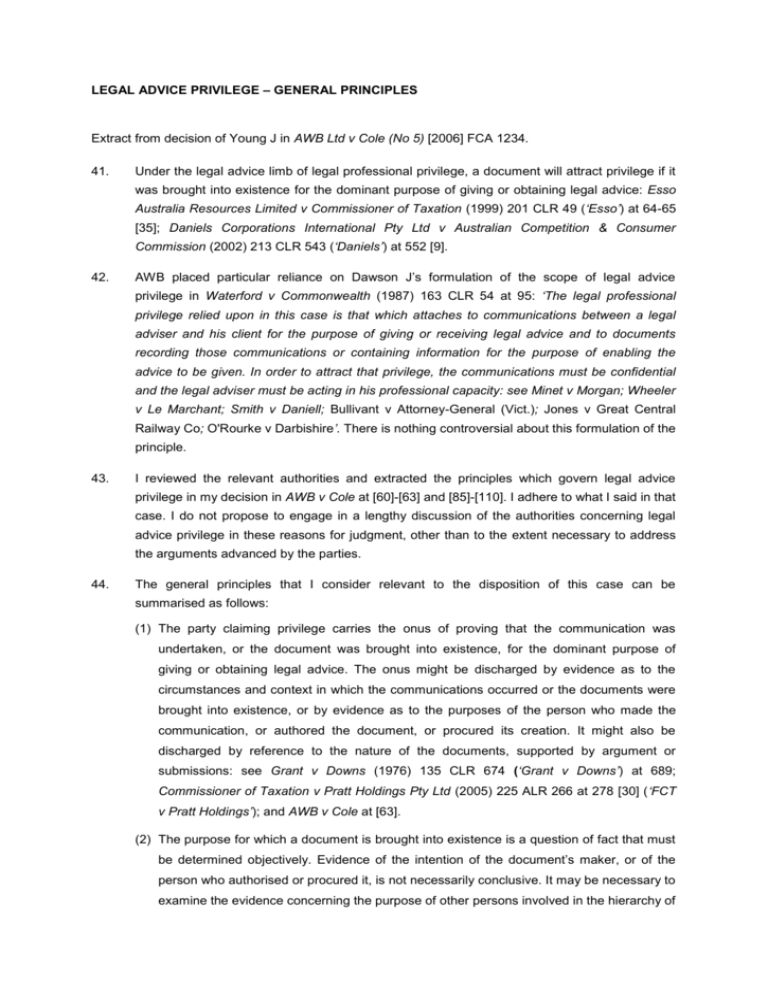

LEGAL ADVICE PRIVILEGE – GENERAL PRINCIPLES

advertisement

LEGAL ADVICE PRIVILEGE – GENERAL PRINCIPLES Extract from decision of Young J in AWB Ltd v Cole (No 5) [2006] FCA 1234. 41. Under the legal advice limb of legal professional privilege, a document will attract privilege if it was brought into existence for the dominant purpose of giving or obtaining legal advice: Esso Australia Resources Limited v Commissioner of Taxation (1999) 201 CLR 49 (‘Esso’) at 64-65 [35]; Daniels Corporations International Pty Ltd v Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (2002) 213 CLR 543 (‘Daniels’) at 552 [9]. 42. AWB placed particular reliance on Dawson J’s formulation of the scope of legal advice privilege in Waterford v Commonwealth (1987) 163 CLR 54 at 95: ‘The legal professional privilege relied upon in this case is that which attaches to communications between a legal adviser and his client for the purpose of giving or receiving legal advice and to documents recording those communications or containing information for the purpose of enabling the advice to be given. In order to attract that privilege, the communications must be confidential and the legal adviser must be acting in his professional capacity: see Minet v Morgan; Wheeler v Le Marchant; Smith v Daniell; Bullivant v Attorney-General (Vict.); Jones v Great Central Railway Co; O'Rourke v Darbishire’. There is nothing controversial about this formulation of the principle. 43. I reviewed the relevant authorities and extracted the principles which govern legal advice privilege in my decision in AWB v Cole at [60]-[63] and [85]-[110]. I adhere to what I said in that case. I do not propose to engage in a lengthy discussion of the authorities concerning legal advice privilege in these reasons for judgment, other than to the extent necessary to address the arguments advanced by the parties. 44. The general principles that I consider relevant to the disposition of this case can be summarised as follows: (1) The party claiming privilege carries the onus of proving that the communication was undertaken, or the document was brought into existence, for the dominant purpose of giving or obtaining legal advice. The onus might be discharged by evidence as to the circumstances and context in which the communications occurred or the documents were brought into existence, or by evidence as to the purposes of the person who made the communication, or authored the document, or procured its creation. It might also be discharged by reference to the nature of the documents, supported by argument or submissions: see Grant v Downs (1976) 135 CLR 674 (‘Grant v Downs’) at 689; Commissioner of Taxation v Pratt Holdings Pty Ltd (2005) 225 ALR 266 at 278 [30] (‘FCT v Pratt Holdings’); and AWB v Cole at [63]. (2) The purpose for which a document is brought into existence is a question of fact that must be determined objectively. Evidence of the intention of the document’s maker, or of the person who authorised or procured it, is not necessarily conclusive. It may be necessary to examine the evidence concerning the purpose of other persons involved in the hierarchy of 2 decision making or consultation that led to the creation of the document and its subsequent communication: see AWB v Cole at [110]. (3) The existence of legal professional privilege is not established merely by the use of verbal formula: Grant v Downs at 689 per Stephen, Mason and Murphy JJ. Nor is a claim of privilege established by mere assertion that privilege applies to particular communications or that communications are undertaken for the purpose of obtaining or giving ‘legal advice’: National Crime Authority v S (1991) 29 FCR 203 at 211–212 per Lockhart J; Candacal Pty Ltd v Industry Research & Development Board (2005) 223 ALR 284 (‘Candacal’) at 298 [70]; Seven Network Limited v News Limited [2005] FCA 142 at [6]–[8]. If assertions of that kind are received in evidence in support of the privilege claim, their conclusionary nature can leave unclear what advice was really being sought. There will be cases in which a claim of privilege will not be sustainable in the absence of evidence identifying the circumstances in which the relevant communication took place and the topics to which the instructions or advice were directed: Kennedy v Wallace (2004) 142 FCR 185 (‘Kennedy v Wallace’) at 189–190 [12]–[17] per Black CJ and Emmett J and at 211–212 [144]–[145] and at 215–216 [166]–[171] per Allsop J; see also Southern Equities Corporation Ltd (in liq) v Arthur Andersen & Co (No 6) [2001] SASC 398. (4) Where communications take place between a client and his or her independent legal advisers, or between a client’s in-house lawyers and those legal advisers, it may be appropriate to assume that legitimate legal advice was being sought, absent any contrary indications: Kennedy v Wallace (2004) 208 ALR 424 at 442 [65] per Gyles J; affirmed on appeal, Kennedy v Wallace at 191-192 [23]- [27] per Black CJ and Emmett J. In Kennedy v Wallace, Black CJ and Emmett J inclined to the view that in the ordinary case of a client consulting a lawyer about a legal problem in uncontroversial circumstances, proof of those facts alone will provide a sufficient basis for a conclusion that legitimate legal advice is being sought or given. (5) A ‘dominant purpose’ is one that predominates over other purposes; it is the prevailing or paramount purpose: AWB v Cole at [105]-[106]; FCT v Pratt Holdings at 279-280 [30] per Kenny J. (6) An appropriate starting point when applying the dominant purpose test is to ask what was the intended use or uses of the document which accounted for it being brought into existence: Pratt Holdings Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (2004) 136 FCR 357 at 366 [35] per Finn J. (7) The concept of legal advice is fairly wide. It extends to professional advice as to what a party should prudently or sensibly do in the relevant legal context; but it does not extend to advice that is purely commercial or of a public relations character: Balabel v Air India [1988] 1 Ch 317 (‘Balabel’) at 323 and 330; Nederlandse Reassurantie Groep Holding NV v Bacon and Woodrow [1995] 1 All ER 976 (‘Nederlandse’) at 983; Three Rivers District Council v Governor and Company of the Bank of England (No 6) [2005] 1 AC 610 (‘Three 3 Rivers’) at 652-653 [43]-[44], 657-658 [59]-[60], 681 [114] and 683 [120]; Dalleagles Pty Ltd v Australian Securities Commission (1991) 4 WAR 325 (‘Dalleagles’) at 332-333; DSE (Holdings) Pty Ltd v Intertan Inc (2003) 135 FCR 151 (‘DSE’) at 161-173 [25]–[71]; and AWB v Cole at [100]-[101]. (8) Legal professional privilege protects the disclosure of documents that record legal work carried out by the lawyer for the benefit of the client, such as research memoranda, collations and summaries of documents, chronologies and the like, whether or not they are actually provided to the client: Daniels at 563 [44] per McHugh J; Commissioner of Australian Federal Police v Propend Finance Pty Ltd (1997) 188 CLR 501 (‘Propend’) at 550 per McHugh J; Dalleagles at 333–334 per Anderson J; Trade Practices Commission v Sterling (1979) 36 FLR 244 (‘Stirling’) at 245–246 per Lockhart J; and Kennedy v Lyell (1883) 23 Ch D 387 at 407; Lyell v Kennedy (1884) 27 Ch D 1 at 31 per Bowen LJ; Propend Finance Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Australian Federal Police (1995) 58 FCR 224 at 266 per Lindgren J. (9) Subject to meeting the dominant purpose test, legal professional privilege extends to notes, memoranda or other documents made by officers or employees of the client that relate to information sought by the client’s legal adviser to enable him or her to advise: Stirling at 246. The privilege extends to drafts, notes and other material brought into existence by the client for the purpose of communication to the lawyer, whether or not they are themselves actually communicated to the lawyer: Saunders v Commissioner of Australian Federal Police (1998) 160 ALR 469 at 472. (10) Legal professional privilege is capable of attaching to communications between a salaried legal adviser and his or her employer, provided that the legal adviser is consulted in a professional capacity in relation to a professional matter and the communications are made in confidence and arise from the relationship of lawyer and client: Waterford v Commonwealth (1987) 163 CLR 54 at 96 per Dawson J; see also Deane J at 79–82. Some cases have added a requirement that the lawyer who provided the advice must be admitted to practice: see Dawson J in Waterford at 96; GSA Industries (Aust) Pty Ltd v Constable (2002) 2 Qd R 146 at 150; Glengallan Investments Pty Ltd v Arthur Andersen (2002) 1 Qd R 233 at 245. However, in Commonwealth v Vance (2005) 158 ACTR 47, the Full Court (Gray, Connolly and Tamberlin JJ) did not regard the possession of a current practising certificate as an essential precondition to the availability of legal professional privilege: at [23]–[35]. The same view was taken by Lee J in Candacal at 303 [99], by Gillard J in Australian Hospital Care (Pindara) Pty Ltd v Duggan [1999] VSC 131 at [111], and by Downes J in Re McKinnon and Secretary, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (2004) 86 ALD 780 at 785 [51]. (11) Legal professional privilege protects communications rather than documents, as the test for privilege is anchored to the purpose for which the document was brought into existence. Consequently, legal professional privilege can attach to copies of non-privileged 4 documents if the purpose of bringing the copy into existence satisfies the dominant purpose test: Propend at 507 per Brennan CJ, 544 per Gaudron J, 553-554 per McHugh J, 571-572 per Gummow J, and 587 per Kirby J. In Propend at 512, Brennan CJ added a qualification to this principle: if an original unprivileged document is not in existence or its location is not disclosed or is not accessible to the persons seeking to execute the warrant, and if no unprivileged copy or other admissible evidence is made available to prove the contents of the original, the otherwise privileged copy loses its protection. (12) The Court has power to examine documents over which legal professional privilege is claimed. Where there is a disputed claim, the High Court has said that the court should not be hesitant to exercise such a power: Esso; see also Grant v Downs at 689. If the power is exercised, the court will need to recognise that it does not have the benefit of submissions or evidence that might place the document in its proper context. The essential purpose of such an inspection is to determine whether, on its face, the nature and content of the document supports the claim for legal professional privilege.