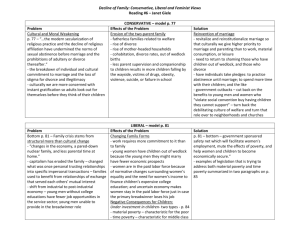

Exercises: J. Geffen

advertisement

Changing Family Forms By: M. Therese Seibert and Marion C. Willets From: Social Education, January-February 2000 Exercises: J. Geffen 5 10 15 20 25 30 1. Public debate over the condition of family as an American institution continues as we enter the new millennium. A number of trends underlie this debate. Divorce is common: more Americans are single or living with a partner outside of marriage, an increasing percent of children are living with only one parent, and a growing percentage of married couples are foregoing parenthood altogether. The result of all these changes is that far fewer families consist of a married couple with children than was the case fifty years ago. 2. For many conservatives, these trends seem to portend the ultimate demise of family. A more progressive view is that this institution is not dying, but rather, changing in form. Progressives argue that the alarming rhetoric over changes in families comes from traditionalists who define the institution only in terms of a stable marriage. Some traditionalists, such as David Popenoe, restrict the definition even further, contending that children must be present within a marriage for a true family to exist.1 3. American sociologist Talcott Parsons, whose theories dominated sociological thought during the 1940s and 1950s, advocated an even more conservative definition of family as a heterosexual couple and their children united by lifelong marriage and prescribed gender roles.2 According to Parsons, the husband’s role should be that of breadwinner and leader, with his status determining the family’s place in society. The wife’s role should be that of the primary caregiver who socializes the children and nurtures and sustains family members. For Parsons, the importance of complementary roles for husband and wife was based on his view that society operates best when its vital needs are fulfilled through task specialization. He saw society as interconnected by a number of major institutions, all fulfilling complementary roles, with families as the nexus of all others. 4. There are many definitions of “family” in popular dictionaries, which is not surprising given the lack of agreement among scholars over what social arrangements constitute a family. Indeed, some scholars (including the authors of this piece) are turning away from even conceptualizing “the family” because it suggests that only one type of family will do. Instead, they are using the term “families” in recognition of diverse family styles including marital couples (with or without children), single parents and their children, cohabitating heterosexual couples, and gay and lesbian couples, among others. Hence, the distinction between “the family” and “families” is not trivial; it is loaded with moral and political significance. Changing Family Forms / 2 35 40 45 50 55 60 5. The U.S. Bureau of the Census defines family as “a group of two people or more (one of whom is the householder) related by birth, marriage, or adoption and residing together.”3 A “family household,” according to the Census, includes additionally “any unrelated people…who may be residing there.” Legal definitions of family vary across state lines, but typically define a family as those related by blood or law. Some states also consider heterosexual adults living together a family unit, as in the case of common law marriage. 6. While official definitions of family are necessary for public policy purposes (for example, determining inheritance rights or tax codes), they do not reflect the reality of most Americans’ lives. For example, parents who do not live with their grown children are not in a family with those children when using the Census definition. Likewise, married couples who live apart for educational or work reasons but maintain their relationship are not considered families. Indeed, individuals living alone have no family at all according to the Census Bureau. 7. We define a family as consisting of at least two individuals who provide sustained emotional support by sharing a residence, sharing a legal or biological tie, or maintaining frequent contact. Of course, one may argue that this is a definition of friendship as much as it is of family. But many Americans accept this definition; indeed, one poll that asked people what constitutes a “family” found the majority agreed with its definition as “a group of people who love and care for each other.”4 Trends in Family Forms While our cultural definition of family reflects how many Americans define and apply the concept, we must use official definitions when reporting Census Bureau data. Three important facets of the contemporary family measured by Census statistics involve marriage and divorce, declining fertility, and the rise of single-headed families. Marriage and Divorce Trends Table 1: Past, Present and Future Marriage Trends in the U.S. 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 1998 2010 (est.) % Never Married Female Male n.a. n.a. 19.0 25.3 22.1 28.1 22.5 30.0 22.8 29.9 24.7 31.2 23.6 29.9 Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census *Divorce rate per 1,000 population. Divorce Rate* n.a. 2.6 2.2 3.5 5.2 4.7. n.a. Age – First Marriage Female Male 20.3 22.8 20.3 22.8 20.8 23.2 22.0 24.7 23.9 26.1 25.0 26.7 n.a. n.a. Changing Family Forms / 3 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 100 105 9. Table 1 uses Census data to describe changing patterns of marriage and divorce as well as future projections. Between 1960 and 1998, the proportion of Americans age 15 and over who had never married increased from 19% to almost 25% among women, and from about 25% to about 31% among men. This change was greatest during the 1960s and the 1990s. 10. Table 1 also shows that a substantial increase in the divorce rate began in the 1960s and crested in the 1980s, leveling of at a relatively high rate since then. Approximately 40% of people who have recently married for the first time are expected to experience divorce (though some estimates are as high as 60%). And, because many people divorce several times, an even higher percent of all marriages are considered likely to end in divorce.5 11. Despite the fact that more American adults have never married or have experienced divorce, marriage as an institution is likely to remain stable well into the future. Most Americans appear to be delaying marriage rather than foregoing it altogether, as evidenced by the increase in average age at first marriage since 1960. Moreover, as Arland Thornton has documented, surveys conducted from 1960 to the present consistently show that the vast majority of Americans expect to marry at some point in their lives.6 12. Another sign that Americans support marriage is that most people who divorce also remarry.7 Approximately 75% of divorced men and women remarry within two years following the divorce. This, coupled with the fact that 60% of divorces involve children, has contributed to the rise of blended families consisting of stepparents, stepchildren, and, possibly, half-siblings.8 Approximately 25 to 30% of American children will spend some part of their lives in such families.9 13. Some researchers argue that the transition to a new family can be harder on children than their parents’ divorce, because of the possibilities for more stressful events. Some children may instantly acquire one or more new siblings, which “can pose a threat to even the most secure child.”10 When both spouses bring children into the new marriage, some display favoritism, either by preferring their own children or by being more lenient with stepchildren in order to gain their approval. Stepchildren often define stepparents as “taking over” as they assume household responsibilities. Stepchildren must also interact with a host of new relatives -–in fact, two sets of them, if both parents remarry. Fertility Trends 14. The total fertility rate, which indicates on average the number of children a woman will bear over her lifetime, is considered one of the most reliable measures of age structure. The total fertility rate in the United States declined steadily from 1800 (.70) to 1940 (2.2). As our nation experienced the Baby Boom following World War II, this rate increased to 3.0 ion 1950 and to 3.5 in 1960, then resuming its historical pattern of decline to 1.8 in 1980.11 Since then, the total fertility rate has risen slightly to 2.0 in 1996, with a projected rate of 2.1 in 2010.12 Changing Family Forms / 4 110 115 15. But while total fertility has declined overall since 1950, non-marital fertility has increased significantly. The non-marital fertility rate (reported here as live births per 1,000 unmarried women) increased from 14.1 in 1950 to 43.8 in 1990.13 However, this rate has declined over the past three years, one explanation for this being a 16% drop in teen births from 1991 to 1997.14 Notwithstanding, the percent of all births occurring to unmarried mothers increased from 19.2% in 1980 to 32.4% in 1996.15 This trend partly explains the rise in female-headed families. The Rise in Single-Headed Families 16. Table 2 documents the steep rise in female-headed families since 1950. The proportion of all families with children under 18 headed by single mothers grew from 6.3% in 1950 to 22.1% in 1998. The Census Bureau projects that this trend will level off at 22.3% by 2010. In contrast, the much smaller proportion of families headed by single fathers – 5.2% in 1998 – is expected to continue rising. Table 2: Families With Children Under 18 by Type: 1950-2010 Mother only with Father only with Married couples with children under 18 children under 18 children under 18 1950 6.3% 1.1% 92.6% 1960 8.2 .9 90.9 1970 10.2 1.2 88.6 1980 17.6 2.0 80.4 1990 20.4 3.6 76.0 1998 22.1 5.2 72.7 2010 (est.) 22.3 5.9 71.8 Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census 120 125 130 135 17. Families with children headed by single mothers will obviously be much more prevalent than those headed by single fathers in coming decades. Relatively high nonmarital fertility is only one reason for this. Also important are the high divorce rate and the fact that mothers are awarded custody of children in the vast majority of divorces. Thus, the societal changes that account for both divorce and the rise in nonmarital fertility have indirectly brought about the rise in female-headed families. 18. So many children living with only their mothers will continue to present challenges to our society come the new millennium. This family form is more prone to poverty than other types of families.16 While the child poverty rate was lower in 1996 (20.5%) than it was in 1960 926.9%), it has generally followed an upward trend since it stood at only 15.5% in1970. 19. Current political debate on how to end poverty is likely to continue to reverberate in the coming years. Conservatives argue that the way to eradicate poverty lies in keeping families together and ending welfare payments which, they say, promote out-of-wedlock births. In contrast, liberals maintain that the government has Changing Family Forms / 5 140 145 150 155 160 a social responsibility to keep children out of poverty, and that providing an economic safety net is a way to sustain and strengthen families. Trends in Perspective 20. Table 3 uses Census definitions to provide a distribution of household types from 1950 to 2010. It indicates that the percent of households consisting of nonfamily members has increased from 10.8% in 1950 to 30.9% in 1998, with the trend projected to continue upward. Among family households, there has been an increase in both female-headed and male-headed families, and a corresponding decrease in households with married couples, from 78.3% in 1950 to 53.0% in 1998. This trend is expected to continue downward. Table 3: Household Types: 1950-2010 Types of Family Households Non-Family Households Married Female-Headed Male-Headed Couples Families Families 1950 78.3% 8.2% 2.7% 10.8% 1960 74.3 8.4 2.3 15.0 1970 70.6 8.7 1.9 18.8 1980 60.8 10.8 2.1 26.3 1990 56.0 11.7 3.1 29.2 1998 53.0 12.3 3.8 30.9 2010 (est.) 51.7 12.1 4.1 32.2 Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census 21. While these changes in family and household forms alarm family traditionalists, they do not surprise family historians, who remind us that the 1950s family so often held up as an ideal was in fact an anomaly. 22. Stephanie Coontz, author of The Way We Never Were and The Way We Really Are, demonstrates that the high rates of marriage and childbearing, and the low divorce rate of the 1950s, in fact contradicted the prevailing trends in our history.17 for example, while the divorce rate of the 1950s was relatively low (just over 25%), this marked a sharp drop in a rate that had been rising since 1890. Also, age at first marriage during the 1950s was at its lowest in 100 years. It was these developments, coupled with the cult of domesticity, which gave birth to the Baby Boom – a rise in fertility that deviated drastically from previous fertility trends.18 Societal Changes Drive Family Forms 23. These lessons from the past are not the only clues suggesting that a return to the traditional family based on the 1950s ideal is unlikely to occur. Although the American family portrait sketched by Parsons has changed dramatically since the late 1950s, his theory that the institution of families is inextricably linked to other social institutions is supported by research. And the logical consequence is that families will Changing Family Forms / 6 165 170 175 180 185 190 195 200 205 continue to change in form just because they are intertwined with other changing social institutions. Economic Changes Affecting Families 24. Perhaps the most significant force affecting family forms in the past half century has been economic changes prompting mothers to enter the labor force. The majority of mothers, even those with small children, now work for pay. The percentage of married women with children under age six in the labor force soared from 18.6% in 1960 to 63.6% in 1997.19 In fact, “over half of women with a newborn are in the labor force.”20 25. The primary reason for this increase in women’s employment has been the decline in real wages for men since 1973. Women are compensating for this loss in family income by generating their own earnings. Women also work so that their families can keep up with the rising standard of living that has resulted from technological advances. In addition, women have entered the labor force because society needed their skills. As Alice Abel-Kemp explains, work largely performed by women – such as clerical and service work – has been in great demand as society moved from a manufacturing to a service economy.21 26. Other reasons for the rise in female employment include higher education levels for women, the acceptance of more egalitarian gender roles, a search for personal satisfaction, and a decline in fertility. However, it has been difficult to determine whether the drop in fertility prompted women to enter the work force or whether fertility dropped as a consequence of other demands on women’s time. This “chicken and egg” dilemma also applies to how Americans feel about mothers working outside the home. Certainly, sex role attitudes have become more liberal since the 1960s, but research suggests that Americans have become more accepting of working mothers after the fact.22 27. Regardless of why mothers have joined the labor force, their being there has had a profound effect on family dynamics – not least the challenge it poses to the father’s role as family head and sole breadwinner. Family traditionalists criticize these gender role changes, while feminists and progressives celebrate them as a movement toward more egalitarian marriages. Earning their own income helps free women from economic dependency and alleviates the pressure on men to provide all the family income. However, these positive changes have made it easier for both husbands and wives to leave unhappy marriages, thereby contributing to the high rates of divorce and single-headed families. They have also subjected women to a double day of work both inside and outside of the home.23 28. Another consequence of mothers going to work has been a demand for affordable quality daycare. Conservatives do not support placing children in daycare, much less having the federal government subsidize it. They warn of its harmful effects on a child’s capacity for emotional attachment. However, their fears are not generally supported by research, which indicates that children in daycare can still Changing Family Forms / 7 210 215 220 225 230 235 240 form close attachments to their parents. For example, a study by Sandra Scarr and colleagues found that quality daycare appears “to promote better intellectual and social development,” whereas “poor quality care and poor family environments can conspire to produce poor development outcomes…”24 29. Institutional responses to employed mothers have been slow. Work structures are still organized on the premise that mothers are at home caring for the children, resulting in conflicts between work and family that usually fall on women. One governmental response has been The Family Medical Leave Act of 1993. While it permits up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave after the birth of a child or for a family medical emergency, it offers no relief to parents trying to juggle ongoing demands of home and work. Moreover, most parents can not afford to forego pay for 90 days. 30. Public day care is quite limited in the United States, as is affordable, quality private day care. Consequently, only 29% of preschoolers attend either a day care center or a nursery school, and most families rely on relatives for the care of their young children.25 After-school care also is lacking, and 10% of our nation’s youngsters are latchkey kids.26 Cultural Changes Affecting Families 31. In Embattled Paradise, Arlene Skolnick discusses the “cultural earthquake” of the 1960s and early 1970s that changed the shape of American families.27 An overarching message of social movements during this time was the acceptance of diverse lifestyles and cultures. This, along with the Sexual Revolution, set the tone for the popular culture’s acceptance of varying family forms, such as blended families, single-headed households, heterosexual cohabiting couples, gay marriages or homosexual unions, and childfree marriages. Television shows of the 1950s like “Donna Reed”, “Leave It To Beaver”, or “Father Knows Best” have increasingly been replaced with shows focusing on families of different types. 32. The growing popularity of heterosexual cohabitation is particularly offensive to family traditionalists. While only 11% of those first married between 1965 and 1974 had cohabited with someone (usually, but not necessarily, their future spouse) prior to marriage, this rate quadrupled to 44% by 1980-1984. Indeed, between 1960 and the late 1980s, the total number of unmarried heterosexual couples living together increased fivefold.28 Researchers assert that “rarely does social change occur with such rapidity.”29 33. Most cohabitations are short-term arrangements that typically result in legal marriage. The median length of cohabiting unions is 1.3 years, with 60% being transformed into legal marriages.30 Furthermore, the most popular reason to cohabit is to test for subsequent marital compatibility.31 Thus, legal marriage continues to be the ultimate goal of cohabiting for most couples in the United States, particularly among those who have never been married before.32 Changing Family Forms / 8 245 250 255 260 265 270 275 280 285 Legal Changes Affecting Families 34. Lenore Weitzman argues that legal changes such as no fault divorce laws have made it easier for married couples to obtain a divorce.33 One positive consequence of no fault divorce is that couples no longer need to demonstrate desertion, abuse, or infidelity to end legal unions. This empowers couples to decide their own fate with less state control. 35. However, Weitzman points out, the increase in divorce resulting from changes in the law has left many female-headed families at risk for poverty. Relatively few women have been awarded alimony since the rise in female employment, and only about 25% of divorced mothers receive full payment of child support.34 These two facts partly explain why one in five American children continue to live in poverty.35 They may also help explain why almost half of people polled in one 1996 survey thought divorce should be more difficult to obtain.36 Technological Changes Affecting Families 36. Technological changes, and their economic repercussions, have had a tremendous influence on the family as an American institution. Before the Industrial Revolution, most families produced as a single economic unit, with parents and children working together on farms or in businesses. But as industrialization unfolded, family production became splintered with the father emerging as the primary wage earner and the mother as the primary caregiver – at least among middle-class families. The type of family traditionalists long for was actually a product of the Industrial Revolution, while the fact that mother and father now work is reminiscent of preindustrial families. 37. We suspect that technological forces will continue to reshape families and intimate relationships in the future. More couples having difficulty in conceiving children will likely turn to reproductive technologies that may themselves entail new configurations in family forms. Advances in communication technologies, coupled with high female employment, will likely increase the number of long distance relationships and commuter marriages. Conclusion 38. Unless the United States experiences a cultural revolution, traditional families modeled on Parsons’ description are unlikely to regain their position as the dominant family form in America. Because families are part of a nexus of social institutions, they will continue to change in response to institutional and cultural changes. On this point, we agree with Parsons. However, we disagree with his view that social institutions necessarily complement each other. Rather, we think that institutional cultural changes often breed conflict – as is clearly evidenced in the debate over families today. 39. While families have changed in response to other societal forces, institutional and cultural adjustments to changing family forms have been slow in coming. Consequently, parents face conflicting demands between family and work; children Changing Family Forms / 9 290 lack adequate preschool and after-school care; mothers still face a double day of work; blended families face an array of stressful events; children in female-headed families are still at risk for poverty; and family judges must rely on obsolete definitions of families when ruling on family disputes. All of these challenges – and others, perhaps not yet foreseen – will be with us in the years to come unless more institutional support for diverse family styles and the children growing up within them is forthcoming. Notes 1. David Popenoe, “American Family Decline, 1960-1990: A Review and Appraisal,” Journal of Marriage and the Family 55 (1993): 542-572. 2. Talcott Parsons, “The Kinship System of Contemporary United States” in Talcott Parsons, ed., Essays in Sociological Theory (New York: Free Press of Glencoe, 1949). 3. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Population Division, Fertility and Family Statistics Division, Current Population Survey Definitions and Explanations (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1999). 4. Massachusetts Mutual Insurance Company, The Changing American Family (Springfield, MA: Author, 1990). 5. L.L. Bumpass, “What’s Happening to the Family? Interactions Between Demographic and Institutional Change”, Demography 27: 483-498; A.J. Cherlin, Marriage, Divorce, Remarriage, revised and enlarged edition (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992). 6. Arlan Thornton, “Changing Attitudes Towards Family Issues in the United States”, Journal of Marriage and the Family, 51: 873-893; Arland Thornton and D. Freedman, “Changing Attitudes Toward Marriage and the Single Life”, Family Planning Perspectives 14 (1982): 297-303. 7. L.L. Bumpass, J.A. Sweet, and T.C. Martin, “Changing Patterns of Remarriage”, Journal of Marriage and the Family 52 (1990): 747-756. 8. E.M. Hetherington, T.C. Law, and T.G. O’Connor, “Divorce: Challenges, Changes, and New Chances”, in A.S. Skolnick and J.H. Skolnick, eds., Family in Transition, 10th ed. (New York: Addison Wesley, Longman, Inc., 1999). 9. C.R. Ahrons and R.H. Rodgers, “The Remarriage Transition”, in Skolnick and Skolnick. 10. Ibid., 178. 11. The 1800 total fertility rate was reported in A. Coale and M. Zelnick, New Estimates of Fertility and Population in the United States (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1963). The rates for 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, and 1980 can be found in the National Center for Health Statistics, Vital and Health Statistics, Series 21, No. 28. 12. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States 1998 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1998). 13. D. Spain and S.M. Bianchi, Balancing Act (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1996), Table 1.1. 14. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Births: Final Data for 1997,” Vol. 47, No. 18. 96 pp. (PHS) 99-1120 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1997). 15. S. McLanahan and G. Sandefur, Growing up with a Single Parent (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994). Changing Family Forms / 10 17. S. Coontz, The Way We Never Were: American Families and the Nostalgia Trap (New York: basic Books, 1992); S. Coontz, The Way We Really Are (New York: Basic books, 1997). 18. F. Bean, “The Baby Boom and its Explanation,” The Sociological Quarterly 24 (1983): 353-365. 19. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States, 1998, Table 654. 20. A. Bachu, “Fertility 1997: Population Profile of the United States,” in Current Population Reports, Special Studies P23, No. 194 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1997). 21. A. Abel-Kemp, Women’s Work (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1994); B. Bergman, Economic Emergence of Women (New York: Basic Books, 1986). 22. For a review of this research, see D. Spain and S.M. Bianchi. 23. A.R. Hochschild with A. Machung, The Second Shift (New York: Viking/Penguin, 1989); S. Scarr, D. Phillips, and K. McCartney, “Working Mothers and Their Families,” American Psychologist (1989): 1406. 24. Ibid. 25. L.M. Casper, “Who’s Minding Our Preschoolers?”, Current Population Survey Series P70, No. 62 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, Fall, 1994). 26. U.S. Bureau of the Census, “School Enrollment – Social and Economic Characteristics of Students,” Current Population Survey Report Series P70, No. 479 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, October, 1993). 27. A. Skolnick, Embattled Paradise (New York: Basic Books, 1991). 28. P.C. Glick, “American Families: As They Are and Were,” Sociology and Social Research 74 (1990): 139-145. 29. P.C. Glick and G.B. Spanier, “Married and Unmarried Cohabitation in the United States,” Journal of Marriage and the Family 42 (1980): 19-30. 30. L.L. Bumpass and J.A. Sweet, “National Estimates of Cohabitation,” Demography 26 (1989): 615-625; L.L. Bumpass, J.A. Sweet, and A.J. Cherlin, “The Role of Cohabitation in Declining Rates of Marriage,” Journal of Marriage and the Family 53 (1991): 913927, Cherlin. 31. Bumpass. 32. “Partnership Ordinances,” Presented at the 93rd Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association (San Francisco: August 28, 1996). 33. L.J. Weitzman, The Divorce Revolution (New York: Free Press, 1985). 34. L.J. Weitzman, “Child Support: The National Disgrace,” in N.D. Glenn and M.T. Coleman, eds., Family Relations: A Reader (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1988), 349-374. 35. K. Bryson, “1997 Population Profile of the United States,” Chapter 22, Current Population Reports: Special Studies Series P23, No. 194 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1997). 36. J.S. Davis and T.W. Smith, “General Social Surveys, 1972-1996,” (machine readable data file). Principal investigator, T.W. Smith, NORC ed. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center, producer 1996, Storrs, CT: The Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, University of Connecticut, distributor. 1 data file (35, 284 logical records and 1 codebook (1295 pp), 214. Changing Family Forms / 11 Answer in your own words. 1. 2. Answer the question below in English. Describe some of the current trends – paragraph 1 – of family formation prevailing in the U.S.A. Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the question below in English. Compare the conservative reaction to recent developments – paragraph 2 – in family formation to that of the more progressive elements. Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the question below in Hebrew. 3. What, according to Talcott Parsons – paragraph 3 – were the distinguishing characteristics of a normal family? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the question below in Hebrew. 4. What does the fact that popular dictionaries will provide – paragraph 4 – any number of definitions for the word “family” suggest about prevailing attitudes? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ 5. 6. Answer the question below in English. In what way is the definition of “family” – paragraph 6 – by the Census Bureau deficient? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the question below in English. In what way is the definition of friendship – paragraph 7 – not unlike that of family? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Changing Family Forms / 12 Answer the question below in Hebrew. 7. Provide the information – paragraphs 11-12 – that would suggest that the institution of “marriage” as such will surely survive. Answer: _____________________________________________________________ 8. Answer the question below in English. What additional, and potentially more serious, difficulty do the children of divorced parents – paragraph 13 – usually face? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Complete the sentence below. 9. While total fertility rates – paragraph 15 – have been declining quite consistently, non-marital fertility __________________________________________ Study the data provided in Table 2. 10. In what sense are the estimated figures for the year 2010 – as provided in Table 2 – rather surprising? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the question below in Hebrew. 11. What makes the developments in the decade 1970-1980 as indicated in Table 2 so striking? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ 12. Answer the question below in English. How do the authors – paragraphs 16-17 – explain the steep rise in femaleheaded families since 1950? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Changing Family Forms / 13 13. 14. Answer the question below in English. To what do the conservatives – paragraph 19 – trace the growing rates in child poverty? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the question below in English. In what way were family patterns of the 1950s quite unlike – paragraph 22 – the preceding ones? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the question below in Hebrew. 15. What social and economic changes – paragraphs 24-26 – may have induced or compelled women to enter the labour force? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ 16. 17. Answer the question below in English. How and why have divorce rates – paragraph 27 – been affected by the rise in female employment? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the question below in English. In which of the decades referred to in Table 3 were a greater number of people increasingly inclined to forego the traditional pattern of household types? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the question below in Hebrew. 18. Trace the changes that have taken place in the sexual norms and conduct of the young – paragraphs 32-33 – as reflected in the figures pointing to premarital cohabitation. Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Changing Family Forms / 14 Answer the question below in Hebrew. 19. Explain (do not merely translate) the term no fault divorce laws and describe both their positive and negative effects (paragraphs 34-35). Answer: _____________________________________________________________ 20. 21. 22. Answer the question below in English. Give instances of family patterns that have already been, and are likely to be, affected by technological changes (paragraphs 36-37). Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the question below in English. How did average real earnings in the post-industrialization era – paragraph 36 – compare with those of the pre-industrial era? (inferential) Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the question below in English. What is meant by institutional support (paragraph 39)? Answer: _____________________________________________________________