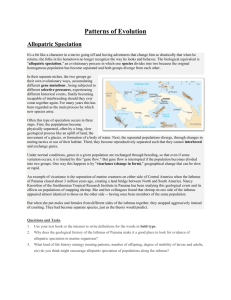

Snapping Shrimp Case

advertisement

It's a bit like a character in a movie going off and having adventures that change him so drastically that when he returns, the folks in his hometown no longer recognize the way he looks and behaves. The biological equivalent is "allopatric speciation," an evolutionary process in which one species divides into two because the original homogenous population has become separated and both groups diverge from each other. In their separate niches, the two groups go their own evolutionary ways, accumulating different gene mutations , being subjected to different selective pressures, experiencing different historical events, finally becoming incapable of interbreeding should they ever come together again. For many years this has been regarded as the main process by which new species arise. Often this type of speciation occurs in three steps. First, the populations become physically separated, often by a long, slow geological process like an uplift of land, the movement of a glacier, or formation of a body of water. Next, the separated populations diverge, through changes in mating tactics or use of their habitat. Third, they become reproductively separated such that they cannot interbreed and exchange genes. Under normal conditions, genes in a given population are exchanged through breeding, so that even if some variation occurs, it is limited by this "gene flow." But gene flow is interrupted if the population becomes divided into two groups. One way this happens is by "vicariance," geographical change that can be slow or rapid. An example of vicariance is the separation of marine creatures on either side of Central America when the Isthmus of Panama closed about 3 million years ago, creating a land bridge between North and South America. Nancy Knowlton of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama has been studying this geological event and its effects on populations of snapping shrimp. She and her colleagues found that shrimp on one side of the isthmus appeared almost identical to those on the other side -having once been members of the same population. But when she put males and females from different sides of the isthmus together, they snapped aggressively instead of courting. They had become separate species, just as the theory would predict. In your groups, discuss the following: Why does the geological history of the Isthmus of Panama make it a good place to look for evidence of allopatric speciation in marine organisms? What kind of life history strategy (mating patterns, number of offspring, degree of mobility of larvae and adults, etc) do you think might encourage allopatric speciation of populations along the isthmus? What life history strategies might encourage, not only allopatric speciation, but the kind of speciation that Schneider and his colleagues hypothesize among Ecuadorian hummingbirds?