Group living, vigilance and foraging

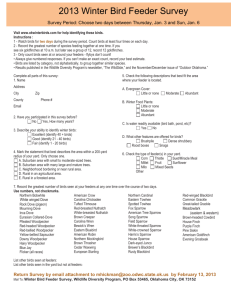

advertisement

ECOL 487L, Animal Behavior Lab Lab#7: Vigilance- foraging tradeoff During the JWatcher lab two weeks ago, we watched several videos of foraging animals to compare the time they allocate to foraging and vigilance. By watching house finches, we ask a similar question this week. We will be observing how risk of predation affects foraging behavior, and whether different group sizes influence how much time animals allocate to foraging versus vigilance. Group living, vigilance and foraging The behaviors that maximize animals energy gain and fitness, such as foraging and mating often make them vulnerable to predators. In order to avoid being attacked, animals frequently raise their heads to scan for predators. However, this reduces the amount of time they can spend on foraging. A strategy that would increase foraging time while reducing scanning time without increasing the risk of predation would be beneficial. One of the advantages of living in groups is the increased safety from predation. This advantage is so important to the animals that it has even been recognized as a possible reason for social evolution (Wilson 1975). Increased safety can either be due to the dilusion effect, which predicts that any individual in a large group has a lower chance of being preyed on (summarized in Roberts 1996), or due to an increased chance of predator detection when more animals are scanning for predators. A large number of studies have documented that in group living animals, individuals foraging in groups will forage for longer periods while scanning for predators less frequently than individuals that forage alone. The observed decrease in vigilant behavior is even more pronounced when individuals forage in larger groups (Roberts 1996). Several theoratical models and some empirical data has also shown that the physical location of individuals within the group also influences whether they are vigilant or not (Fernandez-Juricic et al. 2004) Questions We will be watching house finches at feeders to address the following questions: 1) Does the time allocated to foraging and vigilance change when individuals are in a group? 2) What influence does the group size have on foraging and vigilance? 3) Does location of individuals in the group affect their foraging and vigilance behavior? Based on the information above, what would your predictions for each of these questions be? For more information on the vigilance-foraging tradeoff, you can read two papers that are among the most influential papers on the topic: Bednekoff and Lima (1998) and Gilberts (1996), see references below. Instructions We will divide into four groups and visit bird feeders on campus. Hawks are known to prey on birds at feeders, and two of the feeders we will visit are at high predation areas. For the first few minutes at a feeder, watch the birds without recording any data to familiarize yourself with the amount of turnover that happens in the feeders, and to give the birds some time to adjust to your presence. You can watch the birds that are at the feeders as well as the birds that are on the ground around the feeders. Then, pick one individual, start your stopwatch, and record data on: 1) Time of observation 2) Whether it is feeding or vigilant. Define vigilant behavior as not picking seeds from the feeder and looking away from the feeder (may be looking towards you). 3) How many birds are at the feeder (and/or on the ground) 4) The location of the bird. If it’s on the feeder, are any other birds facing the same way as it is? If it’s on the ground, is it close to the feeder, or away from the feeder? If there are several birds on the ground, where is the one you’re watching located in comparison to others? Are the birds feeding and eating at the same time – how mutually exclusive are these behaviors? After about 15 minutes of taking detailed observations on individual birds, focus your attention on taking data for the analysis. Work together as a group to do this. As a group, decide if you wish to focus on one species or several, and birds on the ground or feeder. This may vary with the activity level of your feeder. Also determine a definition of “flock:” for instance, all birds within a 2-foot radius, or all birds directly adjacent to one another. Record these group-specific data on the top of your data sheet and please stick to this information for the rest of the lab. Next, try each of two data collection methods to record flock size and vigilance. First, use focal individual sampling. Choose a focal bird and record data on this bird for 2 minutes – record the total number of separate times the birds look up and scan for predators (birds on the ground may tilt their head). At the start and ending of the two minute period, count the number of birds in the flock. Aim to get focal sampling data on at least two birds (per person): following scan sampling, compile the data within your group. Second, shift your attention to the overall dynamics of the group and try scan sampling. Every two minutes, count the number of birds present, and record the number of birds engaged in each behavior (vigilant/foraging). You may wish to, as a group, divide the space into focal areas (e.g., one person watches the area to the left, etc.). After observations, compile the data for your group, and turn into the TA. Statistics: In order to address the question of how group size influences the time allocated to foraging and vigilance separately, we will use linear regression. For examples of graphs of data analyzed by these tests, refer to the statistics handout from the Desert Museum lab. Stay tuned for another handout (available on Thursday) with more details on how to analyze your data for your lab report. Note: While you are watching the birds, keep in mind another aspect of vigilant behavior. Some animals have long bouts of vigilant behavior, where they cease foraging for a long time to watch for predators. This behavior is called sentinel behavior, and has been the subject of much research in birds and mammals. Results of some studies showed that animals became more sentinel when they were well-fed (Bednekoff and Woolfenden 2003). Do you think that watching birds forage on feeders where they have constant access to food could have influenced the results of our study? If we were to repeat the study in an environment with less resources, how different would our results be? For the lab report: In addition to your graphs and statistical results, include (in introduction) your predictions for the three questions we addressed today. Question #2 is the one we hope to address with the analysis detailed above, but your preliminary observations should be applicable to questions 1 and 3. In discussion, you might include your ideas on the sentinel behavior issue and whether watching animals at feeders may have biased our results. You may also address possible biases from our experimental design – for instance, we were interested in exposing you to multiple methods, but in doing do, how might this have affects the comparisons over time? We addressed one of the benefits of group living today. What are some of the costs of group living? Do you think that some of those costs could be the reason why some animals do not live in groups? Why or why not? References: Bednekoff, P.A.& Woolfenden, G.E. 2003. Florida scrub-jays (Aphelocoma coerulescens) are sentinels more when well-fed (even with no kin nearby). Ethology, 109, 895-903 Bednekoff, P.A.& Lima, S.L. 1998. Randomness, chaos and confusion in the study of antipredator vigilance. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 13, 284-287 Fernandez- Juricic, E., Siller, S. & Kacelnik, A. 2004. Flock density, social foraging, and scanning: an experiment with startlings. Behavioral Ecology 15, 371-379 Gilberts, G. 1996. Why individual vigilance declines as group size increases. Animal Behavior, 51, 1077-1086 Wilson, E.O. 1975. Sociobiology: The new synthesis, Harvard University Press.