Rashes in General Practice

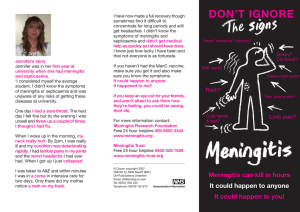

advertisement

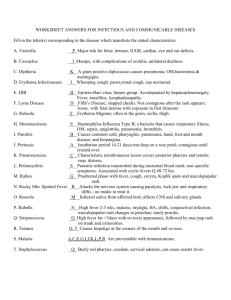

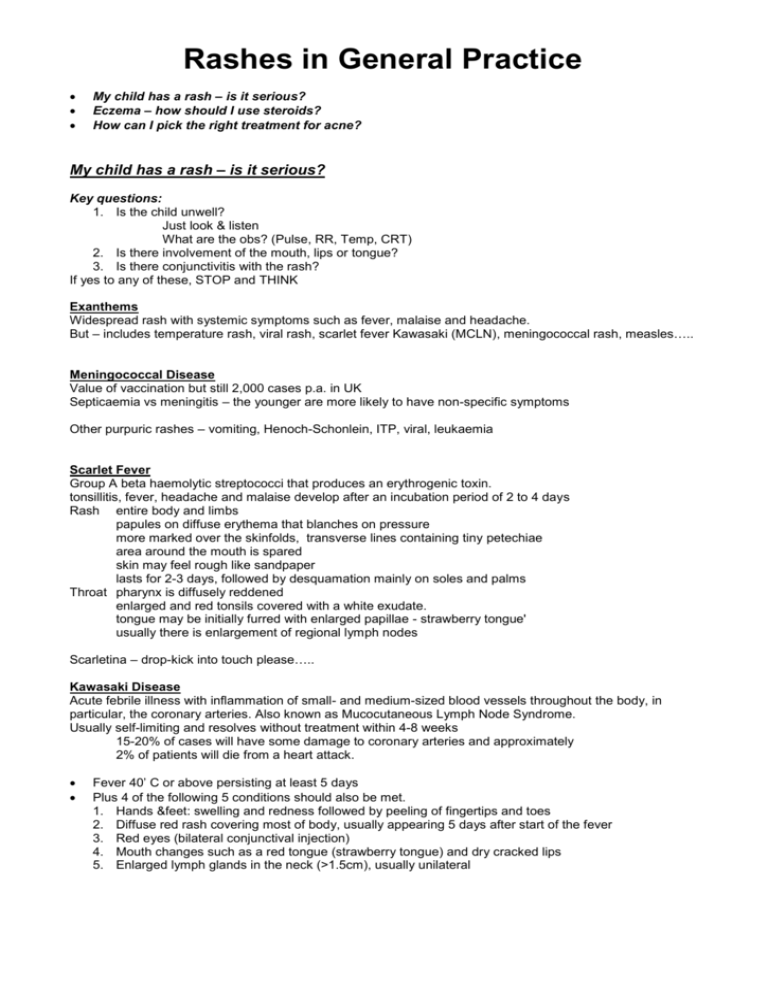

Rashes in General Practice My child has a rash – is it serious? Eczema – how should I use steroids? How can I pick the right treatment for acne? My child has a rash – is it serious? Key questions: 1. Is the child unwell? Just look & listen What are the obs? (Pulse, RR, Temp, CRT) 2. Is there involvement of the mouth, lips or tongue? 3. Is there conjunctivitis with the rash? If yes to any of these, STOP and THINK Exanthems Widespread rash with systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise and headache. But – includes temperature rash, viral rash, scarlet fever Kawasaki (MCLN), meningococcal rash, measles….. Meningococcal Disease Value of vaccination but still 2,000 cases p.a. in UK Septicaemia vs meningitis – the younger are more likely to have non-specific symptoms Other purpuric rashes – vomiting, Henoch-Schonlein, ITP, viral, leukaemia Scarlet Fever Group A beta haemolytic streptococci that produces an erythrogenic toxin. tonsillitis, fever, headache and malaise develop after an incubation period of 2 to 4 days Rash entire body and limbs papules on diffuse erythema that blanches on pressure more marked over the skinfolds, transverse lines containing tiny petechiae area around the mouth is spared skin may feel rough like sandpaper lasts for 2-3 days, followed by desquamation mainly on soles and palms Throat pharynx is diffusely reddened enlarged and red tonsils covered with a white exudate. tongue may be initially furred with enlarged papillae - strawberry tongue' usually there is enlargement of regional lymph nodes Scarletina – drop-kick into touch please….. Kawasaki Disease Acute febrile illness with inflammation of small- and medium-sized blood vessels throughout the body, in particular, the coronary arteries. Also known as Mucocutaneous Lymph Node Syndrome. Usually self-limiting and resolves without treatment within 4-8 weeks 15-20% of cases will have some damage to coronary arteries and approximately 2% of patients will die from a heart attack. Fever 40’ C or above persisting at least 5 days Plus 4 of the following 5 conditions should also be met. 1. Hands &feet: swelling and redness followed by peeling of fingertips and toes 2. Diffuse red rash covering most of body, usually appearing 5 days after start of the fever 3. Red eyes (bilateral conjunctival injection) 4. Mouth changes such as a red tongue (strawberry tongue) and dry cracked lips 5. Enlarged lymph glands in the neck (>1.5cm), usually unilateral Measles Catarrhal stage: prodromal illness with fever, coryza, conjunctivitis, and cough Koplik spots - on the buccal mucosa, especially on the inside of the cheeks sometimes generalised lymphadenopathy irritability (feeling “measly”) Exanthematous stage: maculopapular rash appears 3 to 5 days later firstly behind the ears, then down the body, becoming confluent, fading by the third day Other Paediatric Rashes The above are interesting and potentially dangerous Most “Paediatric Infection Rashes” will be viral exanthema and of no consequence Ones worth reading up: Roseola infantum Chickenpox Urticaria (most common cause in children is viral) Slapped Cheek Molluscum Hand foot & mouth Eczema – how should I use steroids? Where does dry skin end and eczema begin? If eczema = dermatitis, what does “~itis” mean? What treatment options do you have? Moisturiser (emollient) Creams vs ointments vs bath additives Topical steroids Mild – hydrocortisone Moderate – Betamethasone (Betnovate) Potent - clobetasol propionate (Dermovate) Antibiotic Anti-staphylococcal action Systemic (preferred) vs topical Anti-itch Anti-histamines Creams Other options Tacrolimus Referral How safe is it to use steroids? Step up and step down approach (treatment stages & steroid strength) Pulses of 5-10 days (avoid too short, review if need long courses) Always stress importance of moisturiser Understand finger-tip units (patient.co.uk) 1 FTU cover adult hand front & back Follow these rules and use of face, use with infants is OK What about hand eczema? Three-way approach Moisturise Steroid (usually moderate) Protect ++++ Deep fissures – Heelan tape Consider occupational cause Can you recognise seborrhoeic dermatitis? Infantile - cradle-cap Treat with moisturiser Adult – fungal Nasolabial fold, eyebrows, dandruff Treat with Ketoconazole, mild topical steroids Can you recognise (acne) rosacea? Features: Erythema Papules & pustules Telangectasia Sebaceous hypertrophy Treatment Avoid triggers Tetracyclines, never steroids How can I pick the right treatment for acne? Grade acne as mild, moderate & severe Mild Acne Start with otc topical treatments Not inflammatory (papules & comedones) Topical retinoids Inflammatory Benzoyl peroxide Moderate Acne Add in oral treatments Oxytetracycline Skin-friendly COC – Yasmin, Dianette Severe Acne Consider referral for Roaccutane Early if there is large nodules & cysts or “ice-pick” scars Some do’s and don’ts Treatments take 3-4 months to develop full effect Topical antibiotics may encourage antibiotic resistance, especially if you are using a different one orally Minocycline is VERY expensive Interesting websites www.dermnetnz.org www.dermis.net Revised 14.9.10 Assessing Unwell Children Age in Years <1 1-2 2-5 5-12 Over 12 Heart Rate / Min 110-160 100-150 95-140 80-120 60-100 Resp Rate/Min 30-40 25-35 25-30 20-25 15-20 Systolic BP 70-90 80-95 80-100 90-110 100-120 A recent, national study found that almost 50% of children presenting to GPs with meningococcal disease were sent home on their first visit and that these children were more likely to die. The study found that the first symptoms reported by parents of children with meningitis and septicaemia were common to many self-limiting viral illnesses. This prodromal phase lasted up to 4 hours in young children but as long as 8 hours in adolescents, followed by the more specific and severe symptoms of meningitis and septicaemia Red Flag Signs of Early Septicaemia In all age groups, signs of septicaemia and circulatory shut-down were next to develop – 72% of children had limb pain, pale or mottled skin, or cold hands and feet at a median time of 8 hours from the onset of illness. Parents of younger children also reported drowsiness, rapid or laboured breathing, and sometimes diarrhoea. Thirst was reported in older children. Classic Symptoms These tended to present later. The first classic symptom was a rash, which appeared at 8-9 hours (median time) in babies and young children, but later in older children. Although not always present, it was the most common classic feature of meningococcal disease. Meningitis symptoms (neck stiffness, photophobia, bulging fontanelle) appeared later – 12 to 15 hours from onset. They were more common in older children and were not reliable signs in children under age 5. NICE Guidelines on Feverish Illness in Children specify that temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate and capillary refill time should be routinely measured and recorded in all feverish children aged under five. A respiratory rate of >60 breaths/minute is classified as ‘red’ in the NICE traffic-light system, requiring urgent referral to a paediatric specialist. NICE classifies children with RR >50 at 6-12 months of age or RR >40 at >1 year of age to be at intermediate risk of serious illness: they should be assessed face-to-face and their need for paediatric care considered. A raised heart rate can be a sign of serious illness, particularly septic shock. You should check capillary refill by pressing for 5 seconds on the big toe or a finger, or on the sternum, and count the seconds it takes for colour to return. Capillary refill time ≥3 seconds signals intermediate risk of severe infection1, and when prolonged to ≥4 seconds on peripheries, especially with raised heart and respiratory rates, suggests shock. If a pulse oximeter is available you should check oxygen saturation: normal value is >95% in air. Hypotension is an important sign in adults, but it is a late and ominous sign in children, which limits its diagnostic value. Children and adolescents can compensate for shock and maintain normal blood pressure until septicaemia is far advanced. Drowsiness/impaired consciousness in children with septicaemia is a late and grave prognostic sign and indicates immediate action. True neck stiffness can be assessed by checking whether a patient can kiss their knees, or by assessing the ease of passive flexion in a relaxed patient. Neck stiffness signifies meningitis, but is absent in septicaemia. It is not common in young children even with meningitis, so the absence of neck stiffness in a febrile child is NEVER reassuring. Antibiotic Therapy If meningococcal infection is suspected, the patient should be transferred to hospital by the quickest means of transport, usually an emergency ambulance, and parenteral antibiotics should be given at the earliest opportunity usually while arranging transport to hospital. Urgent transfer to hospital is the key priority. The evidence on effectiveness of pre-hospital antibiotics is inconclusive, because disease severity is a confounding factor. Current guidelines advise giving parenteral antibiotics for suspected meningococcal disease at the pre-hospital stage. Antibiotics can be administered IV, IM, or IO. IM antibiotics should be given as proximally as possible, into a part of the limb that is still warm (the cold area being more poorly perfused). Choice of antibiotic: Pre-hospital administration of Benzylpenicillin has been recommended since 1988, and expert guidelines continue to recommend that all GPs carry it and inject it unless there is a history of immediate allergic reactions after previous penicillin administration. GPs do not need to carry alternative antibiotics, but third generation Cephalosporins (Cefotaxime rather than Ceftriaxone for first line use in meningococcal septicaemia) and Chloramphenicol are recommended alternatives if available. Thamesdoc carries Benzylpenicillin, Cefotaxime and Chloramphinicol. Paramedics have the mandate to give Benzylpenicillin for suspected meningococcal septicaemia with a non-blanching rash, and the Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee and Meningitis Research Foundation have collaborated to produce a guideline for paramedics on this. Transfer to Hospital The patient should be transferred to hospital by the quickest means of transport, usually 999 ambulance. Ambulance control and hospital staff need to know the diagnosis, whether the patient has a non-blanching rash, and especially whether there are serious prognostic signs such as a rapidly evolving rash, shock, or impaired conscious level. A GP referring a patient to hospital should contact the on-call paediatrician/emergency personnel so that they can expect this patient.