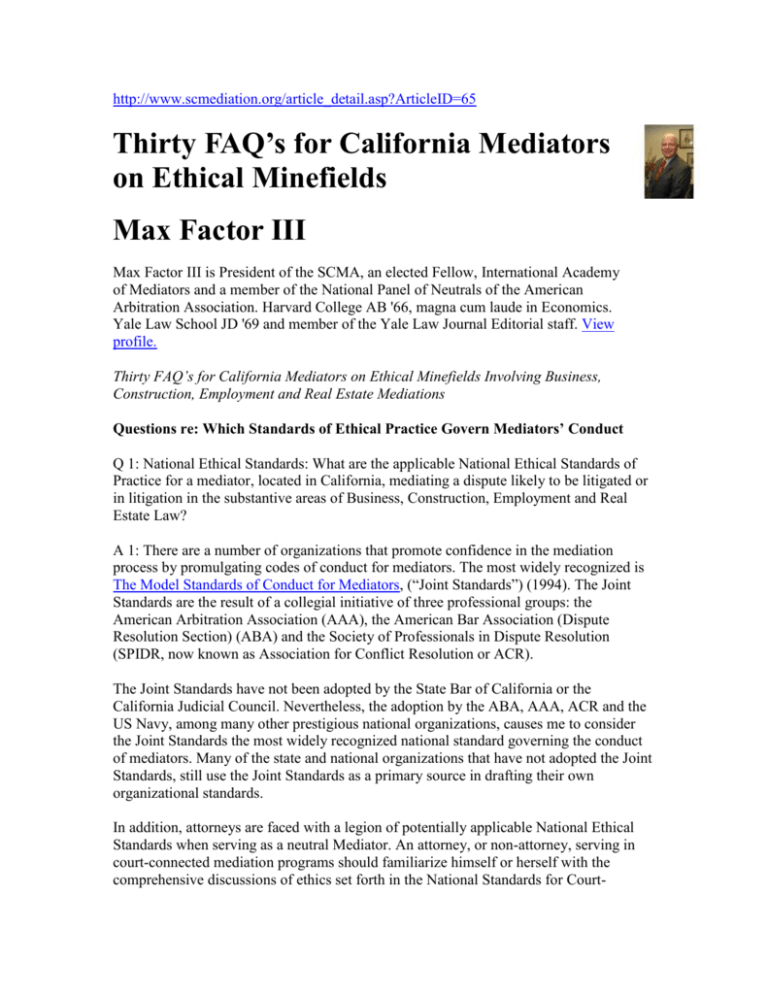

Thirty FAQ`s for California Mediators on Ethical Minefields

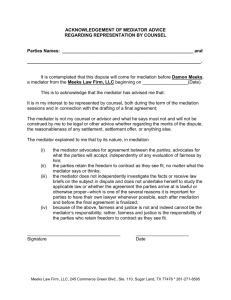

advertisement