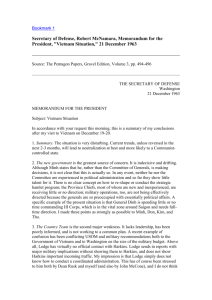

The Situation and Short-Term Prospects in South Vietnam

advertisement