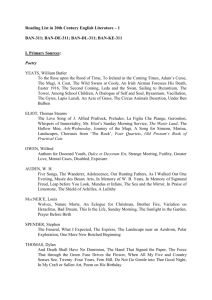

1 BBNAN01200, ENGLISH LITERATURE FROM MODERNISM TO

advertisement

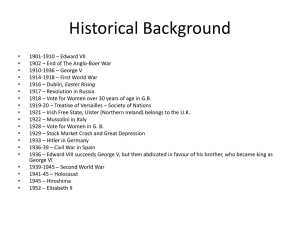

1 BBNAN01200, ENGLISH LITERATURE FROM MODERNISM TO THE PRESENT Modernism and Irish Writing Dr. Michael McAteer, Thursday, November 7, 2013. Yeats and Modernism 1) ‘On Being Asked for a War Poem’ I think it better that in times like these A poet’s mouth be silent, for in truth We have no give to set a statesman right; 2) It has often been said that in the second decade of the twentieth century, Ezra Pound “modernized” Yeats’s style, toughening his attitude and roughening his diction. . . But it now seems clear that Yeats was far more influential in determining the direction of Pound’s career.’ James Longenbach, ‘Modern Poetry’, The Cambridge Companion to Modernism, ed. Michael Levenson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), pp. 10506. 3) ‘The Second Coming’ Turning and turning in the widening gyre The falcon cannot hear the falconer; Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, The blood-dimmed tied is loosed, and everywhere The ceremony of innocence is drowned; The best lack all conviction, while the worst Are full of passionate intensity. 4) On ‘Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen’ ‘The poem is also a belated World War I poem, and a critique of Orange/British and Green violence’. Edna Longley, The Living Stream (London: Bloodaxe, 1994), p. 80. The rage-driven, rage-tormented, and rage-hungry troop, Trooper belabouring trooper, biting at arm or at face, Plunges towards nothing, arms and fingers spreading wide For the embrace of nothing; and I, my wits astray Because of all that senseless tumult, all but cried For vengeance on the murderers of Jacques Molay. 5) On Yeats’s Japanese Noh play At the Hawk’s Well: ‘However traditional in their context, when transposed to the European stage the effect is a radical break with tradition; and as Yeats emphasized, the value of Noh stylization was its “strangeness”. . . Yeats’s aim was to create a form of drama in which the dancer would be inseparable from the dance, in a total unity of theme and expression’. Christopher Innes, ‘Modernism in Drama’, The Cambridge Companion to Modernism, ed. Michael Levenson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), pp. 135. The Musicians Song at the end of At the Hawk’s Well: Come to me, human faces, Familiar memories; I have found hateful eyes Among the desolate places, Unfaltering, unmoistened eyes. O lamentable shadows, Obscurity of strife! I choose a pleasant life Among indolent meadows; Wisdom must live a bitter life. Synge and Primitivism 6) Pegeen: I never cursed my father the like of that, though I’m twenty and more years of age. Christy: Then you’d have cursed mine, I’m telling you, and he a man never gave peace to any, saving when he’d get two months or three, or be locked in the 2 asylumes for battering peelers or assaulting men, the way it was a bitter life he led me till I did up a Tuesday and halve his skull’ J.M. Synge, The Playboy of the Western World, The Complete Plays, second edition (London: Methuen, 2001), p. 189. 7) Sarah: Did you never read in the papers the way murdered men do bleed and drip? J.M. Synge, The Playboy of the Western World, p. 194 8) Sarah: Them that kills their fathers is a vain lot surely. J.M. Synge, The Playboy of the Western World, p. 195. 9) Does Synge’s Playboy compare to the primitivism of Joseph Conrad (Heart of Darkness) and D.H. Lawrence, Women in Love? ‘To Conrad, Europe is a museum of moribund values, and Africa horrific yet vital, a home of the primitive, providing a means of access to “the essential”. In a worldview which chimes with those of evolutionist anthropologists, Conrad portrays sailing up the Congo as a voyage into our own prehistory, with the jungle able to awaken “forgotten and brutal instincts, . . . the memory of gratified and monstrous passions”’. David Bradshaw (ed.), A Concise Companion to Modernism (Oxford: Blackwell, 2003), p. 82. Joyce, Language, Politics 12) ‘He closed his eyes in the langour of sleep. His eyelids trembled as if they felt the vast cyclic movoment of the earth and her watchers, trembled as if they felt the strange light of some new world. His soul was swooning into some new world, fantastic, dim, uncertain as under sea, traversed by cloudy shapes and beings. A world, a glimmer, or a flower? Glimmering and trembling, trembling and unfolding, a breaking light, an open flower, it spread in endless succession to itself, breaking in full crimson and unfolding and fading to palest rose, leaf by leaf and wave of light by wave of light, flooding all the heavens with its soft flushes, every flush deeper than the other’. James Joyce, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) (London: Penguin, 1992), p. 187. 13) To Mr Redmond (leader of the Irish Party) the people of Ireland are a ‘nation’. Yet the leader of the opposition (Tory leader Andrew Bonar Law) told his Blenheim audience: ‘There are two nations in Ireland.’ Whereas this, again, was denied by Sir Edward Carson (Unionist leader in Ireland) that the Irish were not a nation at all’. A.G. Carfter, ‘ “England’s Day of Reckoning”’ (1913) in Modernism: A Sourcebook, ed. Steven Matthews, p. 236 Beckett, Ireland and Nowhere 10) On Lawrence: ‘An overdeveloped European civilisation had, by its nature, excluded its products from so much; it was only on a still dark continent, where forces of disease and death were yet rampant, that people could continue to tap into great sources of vitality’. David Bradshaw (ed.), A Concise Companion to Modernism, p. 83. 11) Christianity and Paganism: ‘When we reflect how often the Church has skillfully contrived to plant the seeds of the new faith on the old stock of paganism, we may surmise that the Easter celebration of the dead and risen Christ was grafted upon a similar celebration of the dead and risen Adonis, which, as we have seen reason to believe, was celebrated in Syria at the same season. James G. Frazer, The Golden Bough (1890-1915) in Modernism: A Sourcebook, ed. Steven Matthews (London: Macmillan, 2008), p. 122-23. Vladimir: He said by the tree. (They look at the tree). Do you see any others? Estragon: What is it? Vladimir: I don’t know. A willow. Estragon: Where are the leaves? Vladimir: It must be dead. Estragon: No more weeping. Vladimir: Or perhaps it’s not the season. Estragon: Looks to me more like a bush. Vladimir: A shrub. Estragon: A bush. Vladimir: A-. What are you insinuating? That we’ve come to the wrong place? Samuel Beckett, Waiting for Godot (1955), 2nd edn. (London: Faber, 1965), p. 6.