IV. Environment and Conflict in History

The database of conflict and environment cases shows a broad variety if issues but at a

high level of inspection. This chapter intends to focus on a select set of cases for discussion and

expansion of themes. The plan is to provide a basic typology of major issues and to follow them

through time via selected case studies from the data set.

Human beings are now the most dominant creatures on the planet in their ability to

impact and alter the environment of localities, regions and the planet as a whole. A Brontosaurus

might have held this claim in an earlier era, but their cumulative impact on the planet was surely

far less than the modern human. This dominance needs context. First, our dominance is short

lived compared to other species in other historical time periods. Second, while humans are now

dominant, they are not the most populous of species by either number (behind flies and many

species) or mass volume (behind termites). This chapter attempts to place the ascendancy of

humanity – viewed from the prism of environment and conflict issues -- in a temporal

perspective.

Paul Shepard argues that human conflict was rare until the Agricultural Revolution. The

settlement of humans led to a type of social organization that translated into aggregated power.

This power resulted in the domestication of humans, by other humans. The size of such

communities was much larger than in earlier times and thus created a greater potential for

centralized control and power. The aggregate power became a means of expressing national

interest vis-à-vis other aggregates of urban humanity that were also emerging. Shepard would

not call the agricultural and food production breakthrough a triumph or a revolution. He would

regard it as devolution in the quality of human life and the beginnings of permanent conflict.

154

"Domestication changed means of production, altered social relationships, and increased

environmental destruction. From ecosystems at dynamic equilibrium ten thousand years

ago the farmers created subsystems with pests and weeds by the time of the first walled

towns five thousand years ago...Domestication would create a catastrophic biology of

nutritional deficiencies, alternating feast and famine, health and epidemic, peace and

social conflict, all set in millennial rhythms of slowing collapsing ecosystems."1

Shepard argues that the Agricultural Conjunction completed the subjugation of

environmental and human rights by the development of warrior kingdoms. Usually, these

kingdoms exhausted much of their own environmental resources and used war to make up for

that deficit. The warrior was originally the herder of domestic ungulates: the person who tended

the horses and oxen learned how to ride them in battle. The desire for the hunt combined with

the efficiency of modern social systems led to the growth of state organized military power. The

warrior restored the hunting ethos by changing the focus from animals to humans. These warrior

societies, often built on conquest and slavery, were essentially farming farmers. "The hero, the

warrior, and the cowboy are almost inextricable. For the most part of history they are all

connected to horses or boats, although the Indo-European tool looks especially to the horse."2

A.

The Cases in Context

The concept behind this historical section is not only to examine the evolution of

environment and conflict cases through time, but also to do so in some manner that focuses on

some of the key sub-issues that define this dimension of interaction. Three basic dimensions

1

2

Shepard, Coming Home to the Pleistocene, pp. 82-3.

Shepard, Coming Home to the Pleistocene, p. 115.

155

cover relationships involving environmental breadth, types and status. Each of these dimensions

will include two examples, included as points of comparison and contrast, representing two

major aspects of the dimension (as described earlier). In each time period, six cases are

examined according to the criteria set forward in the prior chapter. These criteria consist of

generic proto-types of behavior along three general dimensions that have dichotomous attributes.

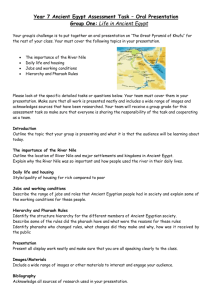

Table IV-1 shows the cases organized by time and in a chronological order. The actual

discussion of the cases follows the chronological order. There are six issues selected: climate

change, forest resources, arable land, water, the environment as a weapon, and the environment

as a conflict boundary.

Table IV-2 shows the cases organized by dimensional issue on a horizontal basis with

temporal sub-sets shown on a vertical basis. The discussion of the cases follows the format in

this table, focusing on three types of issues for three historical periods. This produces a total of

18 case studies. Each issue is then analyzed for comparison and contrast.

156

Table IV-1

Key Cases in Environment and Conflict: Organized by Time

Ancient Cases

Case Name

NEANDERTHAL

CEDARS

MOHENJO

NILE

ASSYRIA

GREATWALL

Onset Year

35,000 BC

2,600 BC

1,700 BC

900 BC

600 BC

200 BC

Describe

The role of

humans in

Neanderthal

extinction

The Cedars of

Lebanon and

conflict over

wood

The decline of

Mohenjo-Daro

and loss of

cropland

Ancient and

modern

conflict over

Nile River

water

Assyrian use

of water as a

weapon

against

Babylonians

China's Great

Wall, Mongols

and the

environment

Type

Climate

Change

Forests

Arable Land Water

Weapons

Boundaries

Middle Cases

Case Name

HADRIAN

MAYA

VINELAND

ANASAZI

ROBIN

HOOD

BUFFALO

Onset Year

150 AD

800 AD

1000 AD

1200 AD

1450 AD

1870 AD

Describe

Hadrian's Wall, Soil, warfare, The Vikings,

Picts, and

and the decline Vineland, and

environmental of Mayas

Native

impact

Americans

Water

resources and

the decline of

the Anasazi

Forests rights The US war

in England with Native

and Robin Americans and

Hood

the buffalo

Type

Boundaries

Water

Forests

Weapons

Arable Land Climate

Change

Modern Cases

Case Name

DMZ

JORDAN

KUWAIT

KHMER

RWANDA

SAHEL

Onset Year

1953 AD

1967 AD

1991 AD

1992 AD

1994 AD

1997 AD

Describe

The Korean

DMZ,

environment

and conflict

Conflict over

the Jordan

River waters

Oil as a cause

and a weapon

in the Kuwait

War

Khmer Rouge

military

support and

timber sales

Population,

deforestation

and conflict

in Rwanda

The expansion

of the Sahel

and Niger

tribal conflict

Type

Boundaries

Water

Weapons

Forests

Arable Land Climate

Change

157

Table IV-2

Key Cases in Environment and Conflict: Organized by Issue

Environmental Environmental Social Type

Social Type

Dimension Breadth

Breadth

Category

Conflict over Conflict over Conflict over Conflict over

General

Specific

Source

Sinks

Resources

Resources

Resources

Conflict

Conflict

Dimension

Dimension

Non-Territory Territory

Type

Climate

Change

Forests

Arable Land Water

Weapons

Boundaries

Ancient

Cases

NEANDERTHAL

CEDARS

MOHENJO

NILE

ASSYRIA

GREATWALL

35,000 BC

2,600 BC

1,700 BC

900 BC

600 BC

200 BC

The role of

humans in

Neanderthal

extinction

VINELAND

The Cedars of

Lebanon and

conflict over

wood

ROBIN

HOOD

The decline of

Mohenjo-Daro

and loss of

cropland

MAYA

Ancient and

modern

conflict over

Nile River

ANASAZI

Assyrian use of China's Great

water as a

Wall, Mongols

weapon against and the

Babylonians environment

BUFFALO

HADRIAN

1000 AD

1450 AD

800 AD

1200 AD

1870 AD

150 AD

The Vikings,

Vineland, and

Native

Americans

SAHEL

Forests rights Soil, warfare, Water

in England and and the decline resources and

Robin Hood of Mayas

the decline of

the Anasazi

KHMER

RWANDA

JORDAN

The US war

with Native

Americans and

buffalo

KUWAIT

Hadrian's Wall,

Picts, and

environmental

impact

DMZ

1997 AD

1992 AD

1991 AD

1953 AD

Oil as a cause

and a weapon

in the Kuwait

War

The Korean

DMZ,

environment

and conflict

Middle

Cases

Modern

Cases

The expansion Khmer Rouge

of the Sahel

support and

and Niger

timber sales

tribal conflict

1994 AD

1967 AD

Population,

Conflict over

deforestation the Jordan

and conflict in River waters

Rwanda

158

The three epochal periods also signify changes in dominant technologies at a macrohistorical level, which in turn indicate changes in structural systems. These systems, in turn,

determine the mechanisms by which environment and conflict relate. Eventually, these changes

impact patterns that may change in direction, from supporting one another to causing conflict

between them.

The approach here is to identify key issues in environment and conflict that persist

throughout time and to follow that relationship to discern how it evolves. The discussion of

these critical issues through time follows a series of case studies illustrating how relationships

change to fit the structural configurations of the time.

B.

Environment and Conflict by Theme over Time

This section examines ancient cases that revolve around the environment and conflict

nexus. By “ancient”, the cases generally occurred before the year 0 in the modern calendar. Six

cases will provide the basis for discussion on differing dimensions of interaction between

conflict and environment. The point is not only to read the cases and their interaction across

places and typologies, but to trace these types of interactions with examples over time. Thus, the

results will combine an examination of both time and place in three historically consecutive case

studies examined through six dimensional issues. The cases from this period tend to focus on the

most basic resources required by early civilizations: land, water, and wood. These needs did not

vanish with time but persist today.

1.

Climate Change

159

The climate cases focus on three peoples -- Neanderthals, Vikings, and Fulani -- who

experienced climate change and conflict in ancient, middle and modern times. The climate

change cases are the oldest in the data set and help define the human experience. Climate change

has both micro- and macro-climate dimensions. The early causes for climate change were driven

solely by nature but in recent years humans have sharply accelerated the process.

There are only five climate change cases in the entire ICE data set.3 No doubt in actual

history there are many more cases. Further, many such cases are much older in time where

records are not sufficient to detail or establish this link.

This type of conflict system has a somewhat dichotomous nature. There are strong links

to short and long-term cases that is focused on a particular resource, eventually results in a

decisive victory, and is associated with habitat change. The average annual conflict deaths might

be few, but the long-time deaths add up to a major conflict (see Figure IV-1).

In ICE cases, this is captured by the attribute “Terra-forming Natural” under the category

“Trigger”.

3

160

Figure IV-1

The Climate Change Causal System (The Yellow Loop in the Conflict Sub-System)

Climate changes cases in ICE are few and diffuse over time. The historical cases then

can provide some insight as to how environmental change generates conflict. These cases have

extremely long-term durations in general, but periods of magnification or change may put this in

a short-term perspective, especially in micro-climates. It appears that this is the case today. The

first case -- regarding the Home Sapiens and Neanderthal wars -- is the longest term conflict

included in the data set and the oldest.

a.

An Ancient Case of Climate Change: The Neanderthal, Humans and the End of the Last

Ice Age

Time Period

Class

Category

Type

Ancient

Environmental Breadth

General Resources

Climate Change

161

The first case study begins with the emergence of the modern human. It largely predates

large scale conflict between groups of humans. At this time, humans were in competition with

other species – as predator and as prey – but also in competition with other primates. This was

especially so since their economic subsistence patterns were quite similar. One of the most

important intra-humanoid disputes was over environment and conflict with human’s closest

ancestor – the Neanderthal.4 Theories about the end of the Neanderthal are controversial and

unresolved. There is, however, no question that human beings played a role in their demise. It is

also true that humans invaded lands that Neanderthals lived on for several hundred thousand

years. Neanderthals survived several ice ages during this period. They could not survive

humans.

Changing climates certainly creates the conditions for conflict as people, their

technologies, and their subsistence patterns all tend to intersect. In some cases, these

technologies and patterns change and adapt as well over time. In other cases, people simply

moved from the changed climate to one that more or less resembles the old climate and therefore

the technologies and economic patterns need not change. Or, the people were displaced, killed

or integrated into other groups.

The conflict over environmental resources is of course inimical to human nature. Clear

evidence for organized human warfare dates back more than nine thousand years, to the early

Neolithic Age.5 It surely existed in the war against the Neanderthals and environment was a key

4

The Neanderthal was first discovered in August 1856 by Dr. Johan Karl Fuhlrott, a

schoolteacher from the town of Elberfed, near the Dussel River in the western part of Germany.

Technically, this was not the first Neanderthal skull ever found. Researchers did not realize until

the 1860s, that a skull found in 1848 at Gibraltar was of a Neanderthal. Fuhlrott's find was in a

valley called Neander (Tal or Thal means valley in German) that produced the name. Thus, the

site and the creature are known as Neanderthal.

5

Ferrill, 1985, p. 20 and Roper, 1975, p. 304.

162

factor in that war at the end of the last Ice Age. Humans spread into Europe during this warming

period, in many instances coming into conflict and ultimately displacing Neanderthals.

Anthropologists generally agree that our species began in Africa and migrated from there

to the other parts of the planet. The general belief is that humans came upon areas uninhabited,

but in fact, these areas often did have other primate competitors who would and did compete

over hunting grounds that provided economic subsistence. The conflict between two primate

species occurred through direct warfare and through indirect warfare. The direct conflict was

probably a draw – with the greater Neanderthal physical attributes matched by the higher

technologies of the humans. Indirect warfare was probably a greater factor as humans proved

more adept hunters than the Neanderthals and took more of the game. This led to larger human

populations and less food for competitors.

Anthropologists and geneticists disagree on the genetic relation of the human to the

Neanderthal. Some believe that Neanderthal was simply another race of humans, perhaps most

similar to aborigines from Australia. Most scholars believe Neanderthals were a completely

separate species. The earliest human remains found in Europe date back 35,000 years.

According to anthropologist Eric Trinkhaus the bones suggest interbreeding between humans

and Neanderthals. Other researchers assert that on the whole there was little or no contribution

to the human gene pool. Human are not directly related to Neanderthals, but they do emerge

from a common tree hundred of thousands of years earlier.6

Neanderthals existed between 350,000 and 30,000 years ago. Perhaps as far back as

100,000 years ago they encountered the first human beings , probably in the Middle East. By

45,000 years ago, humans (Cro-magnons) invaded Europe and Asia and the Neanderthals were

Bob Beale, “Euro jawbone rattles Neanderthal debate”, ABC Science Online, September

24, 2003, News in Science (online). http://www.abc.net/science/news/stories/s952446.htm

6

163

gone in 15,000 years. But this is a long time for two people to co-exist without serious conflict

(or attempted mating), as noted in James Shreeve’s “The Neanderthal Peace”.7 Moreover, they

met differing groups of humans over time, and perhaps they too were in conflict with one group

but at peace with another.

These first humans, the Aurignacians, entered into west Europe but retreated during a

cooling period. They were followed by the Gravettians, who possessed more advanced

technology in weapons and warmer clothing to protect them from the cold. While Neanderthals

only had thrusting spears for close range fighting with animals, the Gravettians threw spears and

other projectiles.8 Neanderthals were intelligent primates with customs and rituals and probably

systems of communication. They were not the mindless brutes depicted in earlier "scientific"

tracts and grade B movies, nor the muscle-bound hulks with hairy backs.

Neanderthal had a long, narrow skull, with a large brain and a bony protrusion over each

eye. Physically, the people were stout and strong, with short limbs and digits, and women had

birth canals that were similar in size to modern human females. Ine find, in modern day Israel,

was discovered at the Kabara Cave in Israel by a joint French-Israeli team. The team found a

hyoid bone, which links muscles of lower jaw and neck, critical to speaking. This find led some

to believe that Neanderthal had language abilities perhaps equal to modern humans.

Neanderthals were beyond humans in physical capabilities, being much stronger and more agile.

It would be wrong to stereotype about Neanderthals because they were a heterogonous

group. The various finds from East Asia, the Middle East, and Europe show great diversity in

form and feature, just as would be found in humans. Neanderthals ranged over a large area and

James Shreeve, “The Neanderthal Peace, Discover Vol. 16 No. 09, September 1995.

Jennifer Viegas, “Neanderthals couldn’t cope with the cold”, News in Science:

Environment and Nature, January 8, 2004, accessed July 31, 2004,

http://www.aabc.net.au/science/news/enviro/EnviroRepublish_1033326.htm.

7

8

164

experienced a wide range of climatic variations that influenced the development of their physical

features and culture. The image of Neanderthal as the brute is slowly being replaced, at least in

the scientific world, by a more sophisticated and advanced creature with social ties, cultural

relations and a people who buried their dead.

Neanderthals were intelligent hominids nearly equal to humans in intelligence. Perhaps

some humans had Neanderthals as acquaintances or as trading partners over their long periods of

co-existence. The human relation and reaction to the Neanderthal is perhaps also a cautionary

tale for how humans might greet aliens from another planet.

This was not the first time the two groups had met. The initial encounters between

human and Neanderthal are thought to have taken place somewhere in the Middle East. It was

probably near present day sites in Israel, Lebanon, Syria and Iraq as both groups expanded

during the warming period. There was a gradual process of displacement and replacement.

Similar to today, this narrow stretch of greenery (the Fertile Crescent) was a corridor for

interaction between Asia, Africa and Europe and a sought after territory. Over time, humans

pushed Neanderthals back into the less hospitable parts of Europe. The Neanderthal retreats

often forced them onto lands where game was not as abundant and temperatures much colder.

This deterioration in access to resources no doubt led to long term pressures on survival (see

Figure IV-2).

Figure IV-2

The Extent of the Neanderthal

165

The in-migration of humans into long-standing Neanderthal resource areas (hunting

grounds) was an early conflict with environment causes. This inter-humanoid conflict is perhaps

like forms of intra-human ethnic conflict, with of course broader differences. Researchers

document a great die-off of certain mega-fauna after human arrival in the Eurasia and the

Americas and perhaps the demise of the Neanderthal is evidence of other extinctions associated

with our past.

Perhaps the Neanderthals did not completely die out. Perhaps they live on in the human

gene pool. During the thousands of years that humans and Neanderthals lived in close proximity

to one another, there were no doubt raids that took females captives as spoils of war (by both

166

sides). Rapes as part of conflict also no doubt occurred. Perhaps children were born to humans

that had some Neanderthal genes or vice-versa. Anthropologist Wolpott believes that intermarriage or at least inter-breeding was common between humans and Neanderthal.

Neanderthal hunting technology was inferior to that of humans and more dangerous. Eric

Trinkhaus notes that animals killed by the Neanderthal would have involved close contact using

little refined, stone implements. Daniel Lieberman and John Shea suggest two other advantages

in economic survival that humans held. First, humans migrated, sometimes over great distances,

and took advantage of seasonality and animal migrations. Neanderthals were much more

sedentary and this in a climate with extremely limited resources. Second, humans were not only

better hunters they were also better gatherers. In the end, it may have been a long-gradual war of

technology and adaptation.

Neanderthals spent far more time hunting for sustenance compared to humans and thus

had less leisure time for developing new tools. Both groups used a basic set of tools known as

Mousterian technology, but the level of refinement by the humans was far superior. They no

doubt adopted some Neanderthal techniques and exceeded them. Neanderthals also were able to

control fire, but not to the extent of humans who used it to make pottery and weapons, for

example.

The evolving view of Neanderthals says little about them, but of course says a lot about

humans. Neanderthals have not changed, human tolerance has, and this change mirrors a new

look at how we view our nearest relatives. Thomas Henry Huxley believed the real measure of

humanity is evident in our relation to other apes and other primates.

167

After the humans finished their conflict with the Neanderthals they apparently started

turning against each other in ancient times. Two recent finds demonstrate this: one in Oregon

and the other in Italy.

The first example is from North America. In 1996 two hikers found a skeleton known as

Kennewick Man near the town of Kennewick, Washington, along the banks of the Columbia

River, just prior to the point where it meets up with the Snake River. (They said they had gone

in a back entrance to an event with a cover charge, which they wished to avoid). The hikers

stumbled upon the bones that only later were found to be ancient, dating back 9,200 years. Little

is known about Kennewick Man because of a dispute over who owns the bones. His remains are

a matter of dispute between scientists who want to study him and Native Americans who claim

him under U.S. Federal Law. There is great debate about his characteristics. There is some

preliminary evidence that he was shot with an arrow. His death may be related to territorial

hunting claims.

On February 4, 2004, the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that scientists may study

the 9,200 year old body. The decision was the lack of existing connections between the modern

tribes and the people of that time. His characteristics are alleged to be different from modern

Native Americans who filed the case (the Umatilla, Yakama, Colville and Nez Perce tribes).9

The second example is from Europe. A couple from Germany, hiking in the Otzal Alps,

happened upon bones later found to be about 5,000 years old. The area was near the Italian and

Austrian border, in fact within 101 yards. The bones belonged to a man they called “Otzi” and

were found a close distance within the Italian border. Belonging to Neolithic culture, he was part

of a sophisticated socio-economy and technology, as shown by the artifacts with him. He was

9

Washington Post, “Kennewick Man Can be Studied, Court Rules”, February 5, 2004,

A19.

168

likely a trader whose ancient path later became Roman roads and the main highways and routes

for north south trade in Europe. “The copper in the ax probably came from the mountains,

which, as the source of valuable metals used to make tools, were worshiped by miners

throughout the world.” 10

Otzi’s best weapon was his bow-stave made of yew for its flexibility and workability.

Many prehistoric bow and arrow systems in Europe relied on the wood of the yew tree. There

was also an axe with a yew handle and a copper blade. The bow of the Iceman was made of

yew, as were most ancient bows, due to its pliability.

b.

A Middle Case of Climate Change: The Vikings, Climate and the North American

Experience

Period

Class

Category

Type

Middle

Environmental Breadth

General Resources

Climate Change

After the invasion of Britain, Rome grew weary of continuous war and built Hadrian’

Wall (more on this later). The wall separated conquered Roman lands to the south from the Picts

and Scots to the north, which were difficult peoples to conquer. The lands the Scots inhabited

were marginal in terms of agricultural productivity and the value of victory seemed little. Over

several hundred years, two distinct systems emerged on each side of the wall. To the north was a

tribal based system still reliant on herding and grazing of animals for subsistence. To the south,

a more market based system grew and increases in population created large sedentary

10

Did "Iceman" of Alps Die as Human Sacrifice? National Geographic News, January 15,

2002. www.nationalgeographic.com

169

populations reliant on cultivating agricultural crops. The social stability provided by the wall

allowed the development of settled lifestyles, power structures and the acquisition of wealth.

These differences grew and accumulated over time and two differing environments and

economies emerged on each side of the wall (see the later story of Robin Hood).

An unpredictable change in climate propelled events. The warming climate around 1000

AD made northern lands hospitable. Viking population surged in Scandinavia and they began

move out to settle more distant lands. After invading Britain, to raid and in some cases settle, the

Vikings traveled to Greenland and later on to North America.

The word Viking comes from the Old Norse “vik”, a bay or harbor. The Viking lifestyle

was a reaction to the lack of arable lands and limited alternative means to survive. Fishing was

not a major occupation for them until the Middle Ages.11 Vikings also included men from

Scandinavia who ventured out to acquire new lands, as well as those who looted and robbed as

an occupation. The Vikings really came into being as a distinct group around 780 AD and

rapidly spread in many directions. To the east, they conquered and traded throughout Russia and

into the Ukraine.

“The Vikings were infamous raiders and looters, but they were also farmers and herders

at home and no less sophisticated in arts and invention than other medieval

Europeans…They were successful ship builders who engaged in ever-widening trade,

east to Russia and south to Rome and Baghdad. In their Iceland colony at the end of the

10th century, these people created the first democratic parliament. Their further western

expansion brought about the first tenuous contact between the Old World and the New."12

11

12

Fitzhugh and Ward, p. 14.

Wilford, 2000.

170

There are many explanations for the Viking migrations that include political,

demographic, or religious factors. No doubt the truth is a blend of these many causal instruments

and played differing purposes for the differing Viking groups that migrated..

"Many theories have been advanced to explain the events that propelled Vikings outward

from their northern homelands: developments in ship construction and seafaring skills;

internal stress from population growth and scarce land; loss of personal freedom as

political and economic centralization progressed; and the rise of Christianity over

traditional pagan belief have all been cited. Probably all are correct in degrees; but the

overriding factor was the awareness of opportunities for advancement abroad that lured

Norsemen to leave their home farms."13

What was remarkable about the journey of the Vikings was that their voyages to the New

World, from the East, effectively made the reach of human beings a global one for the first time

in history. “Our ancestors left Africa between 100,000 and 120,000 years ago. Coming up out

of the Middle East, some of them turned left at Europe, and others turned right into the farther

reaches of Asia. Their descendants would not meet until 100,000 years later, at the Strait of

Belle Island [in New Foundland, Canada].”14 This first global encounter did not have a peaceful

outcome.

“It’s a pity that the first contact between the descendants of the People Who Turned Left

and the People Who Turned Right should have ended in killing. Nevertheless, it is not

surprising. The Vikings were a warrior culture with an in-built contempt for non-farming

peoples and a major problem with impulse control. But frankly, it might well have ended

13

Fitzhugh and Ward, p. 17. Norse artifacts are found in many parts of northeastern North

America, on Greenland and other sites such as Ellesmere and Baffin Islands in Canada.

14

Kevin McAleese, ed., Full Circle: First Contact: Vikings and Skraelings in

Newfoundland and Labrador, St. Johns, Newfoundland, Newfoundland Museum, 2000, p. 8.

171

in fighting no matter who they were, because anybody including another group’s

traditional land is likely to run into trouble.” 15

Why did this convergence occur? “The answer has mostly to do with the climate,”16 but

also the chaos of events that often propels history. "The motivating force for the Norwegians

sailing west, the colonization of the lesser Atlantic islands, and thereafter of Iceland and

Greenland, and the attempted settlement of America, was a need for land and pasture."17

The Vikings controlled large parts of France, Britain, Scotland, the Shetland Islands and

Ireland by 700 AD. Irish priests came to the Faeroe Island around 700 AD and Iceland was

discovered and settled between 860 and 870. The period of expansion was actually quite shortlived and suitable land taken by 930.18 In 962, Eric the Red, kicked out of Norway and two

places in Iceland for murder, was banished and headed west where he happened to find

Greenland. He called it "Greenland", but even with relatively warmer conditions then, this was

quite an exaggeration or a public relations stunt to attract settlers. By 986, he returned with 450

people that later grew to 4,000, all emigrants from Iceland. Later, Leif Ericson, his son, would

venture from Greenland in search of lands to the west.

The Vikings thought the lands they found would be as hospitable as Scandinavia – they

were not. In the northern latitudes, the western edges of continents have better warmer climate

conditions for human settlements, owing to the circulation of winds on the planet and the

Atlantic Gulf Stream. “This explains why 20 million Scandinavians can live at latitudes north of

Goose Bay [Canada] today. It also explains why even 1,000 years ago there were at least a

15

16

17

18

Kevin McAleese, ed., Full Circle, p. 21.

Kevin McAleese, ed., Full Circle, p. 14.

Jones, p. 269.

Jones, p. 277.

172

million farmers in Scandinavia, but fewer than 10,000 hunter-gatherers in Newfoundland and

Labrador.” 19

The westward migration of the Vikings was driven by a warming period around 1,0001,500 AD. A “Little Ice Age” followed and lasted from about 1500-1700. The cooling led to an

eventual cooling of the planet's northern extremes and thus rendering uninhabitable many of the

places the Vikings had settled.

Climate research reinforces the sagas. “During the eleventh and twelfth centuries ice was

virtually unknown in the waters between Iceland and the Viking settlements in Greenland, and

the temperature in these settled areas was 2 degrees centigrade to 4 degrees warmer than at

present. From the beginning of the 13th century a mini-ice age affected the northern hemisphere,

plunging the seawater temperature to between 3 degrees centigrade and 7 degrees (about 23

degrees below the present day temperature). This change was enough to bring the ice further and

further south. Seasonal ice floes began to appear in the sailing lanes and near the settlements;

their quantity increased, the ice season lengthened, and the ice floes were followed by ice

bergs."20

This period of Viking expansion was different from earlier ones. Earlier expansions reenforced a plundering lifestyle. This occupation changed as the Vikings became agriculturalists

and adopted settled lifestyles. "The era of Viking marauding had long since passed. To some

scholars the Norman invasion of England in 1066 was the last great Viking raid; many Normans

were descended from helmeted Vikings who had earlier seized their land."21

19

20

21

Kevin McAleese, ed., Full Circle, p. 15.

Logan, p. 78.

Wilford, 2000.

173

This new lifestyle marked a dramatic change in the socio-economic context of the

Vikings. The lifestyle was context-based in a narrow niche of survival in the mostly northerly

lands inhabited by Lapplanders, Eskimos, etc. This required a stable environment. ”The

[Viking] style of living they developed is called crafting: growing some vegetables, catching

some fish, keeping sheep for wool and meat, raising cattle for milk and meat, and growing

enough hay to see the animals through the winter.” 22 This lifestyle required a fairly static type

of environmental climate.

“During the 13th century the climate appears to have deteriorated, though the facts

regarding this are not fully agreed upon. Climatic tables indicate, after a level,

comparatively ice-free period 860-1200, a sharply rising level of marine ice in the years

around 1260, declining thereafter only to rise again after 1300."23

After 1200, the northern Arctic regions of the planet grew colder, and by the middle of

the fifteenth century, the climate reverted to its earlier state, if not even colder. Over much of

Europe the glaciers advanced, the tree line crept south, and the alpine passes used for trade and

travel were often impassable. “The northern coast of Iceland grew increasingly beleaguered by

drift ice; and off Greenland as the sea temperatures sank there was a disabling increase in the ice

which comes south from the East Greenland Current to Cape Farewell, and then swings north to

enclose first the Eastern and then the Western settlement."24

The Vikings found artifacts in Greenland and Northeast Canada, and as they sailed south

along the coast they could see plumes of smokes that indicated human presence.25 Bjarni

Bardarson accidentally reached North America 986 where he was on a voyage to Greenland but

22

23

24

25

Kevin McAleese, ed., Full Circle, p. 12.

Wahlgren, pp. 24-5.

Jones, p. 308.

Fitzhugh and Ward, p.11.

174

lost his way. Leif Ericsson took an expedition further south in 1002 into Vineland and continued

periodic trips for hundreds of years. "It has been suggested that the motive for such voyages [to

North America in 1347] was more likely for the acquisition of timber for Greenland's

construction needs."26 There were at this time virtually no forest resources on the entire island of

Greenland. "In Greenland, emigration may have be abetted by the fact that "the Norse

population reached the carrying capacity of the habitat, which may itself have been

decreasing."27

"According to the sagas, Ericson's party first headed northwest across Baffin Bay and

came upon a rocky coast they called Helluland, present-day Baffin Island. Then they

sailed south, hugging the shore, to the wooded place they named Markland, probably

Labrador. Finally, they entered a shallow bay and waited for high tide to bring them

ashore to a green meadow. Here at L'Anse aux Meadows, they established a base camp,

their beachhead in Vinland."28

In Newfoundland the Vikings settled in a place known as Vineland, because the early

explorers found wild grapes. (Later accounts verify these events. Adam of Bremen wrote in

1070 that in Vinland "there grow grapes.”) The grapes are further evidence of a warmer climatic

period, compared to today, since these areas are now too cold and wild grapes do not grow there

but have moved further south.

Battling the changes in weather was not the only difficulty the Vikings faced. The

Vikings interacted with the Native Americans who lived there, in terms of both commerce and

conflict. The conflict, though relatively rare, proved fatal for the expedition. "The outbreak of

26

27

28

Fitzhugh and Ward, p. 241.

Fitzhugh and Ward, p. 291.

Wilford, 2000.

175

hostilities between Skraelings [the name the Norse gave them] and Norsemen was decisive for

the Vineland venture. The Norsemen had no marked superiority of weapons, their lines of

communication were thin and overlong, and there was an insufficient reservoir of manpower

back in Greenland."29 The attempt at colonization of Vineland probably lasted only until about

1020.

Soon after the arrivals of the Viking in Greenland, the few trees of birch, willow and

elder were soon depleted and replaced with sorrel, yarrow and wild tansy. When the Greenland

colony disappeared the trees soon returned. Both a cooling climate and human overuse of

resources hurt the Viking chances for survival. As domesticated animals started to die off (cattle

and sheep) "the colonists grew more dependent upon seal for subsistence." 30 In Greenland,

"animals were even more destructive than people in changing local vegetation and ultimately

whole landscapes, reducing forest and shrub lands, and through time, by overgrazing, converting

grasslands to wastelands. These ecological stresses grew more difficult to manage in the harsher

climates to the northwest and accumulated over time, more rapidly as the climate deteriorated

generally after 1350." 31

The demise of Greenlanders probably took a very long time. Some suggest that

Europeans lived there into the early 1500s. Toward the end, the Eskimos massacred many

Greenlanders. (In 1492, ironically, Columbus arrived in North America and announced its

discovery just as the Greenland colony was dieing out.) A combination of forces led to the

demise of the Greenlanders and related to the changing climate and the arrival of too many

people on the island. "I propose, therefore, that there was thus a conjunction of debilitating

29

30

31

Jones, p. 303.

Fitzhugh and Ward, p. 74.

Fitzhugh and Ward, p. 19.

176

forces, environmental (the waxing cold), economic (increasing denudation of the soil, the

wasting away of cattle and the few crops, the dwindling supply of fuel, the pressing competition

with the Eskimos for marine game), psychological (a gradual reduction in the birth rate) and

spiritual (religious deprivation and lack of cultural stimulus)." 32

Climate was only one of many factors that led to the demise of the Greenland colony.

"An explanation that stresses climatic changes and plays down politico-economic factors

probably lies as near to the truth as we can get at the moment. In 1261, this small, self-governing

land came under the control of the King of Norway, who, it is often said, restricted trade. Since

much of Greenland's livelihood depended on the export of goods such as homespun clothe, skins

of oxen, sheep and seals, walrus rope, walrus tusks, and polar bears as well as the importation of

timber, iron, and grain, in particular. Such trade restrictions, it is argued, made life difficult."33

Trade was the only way that the colony could survive.

In Greenland, "the Western Settlement was the first to be deserted. After 1349, the time

of the Black Death, the Eastern Settlement' ties were hard-pressed." 34 The role of the church

grew stronger. "Submitting to the nominal authority of Norway's Kind Hakon the Old in 1261,

the Greenlanders were now subject of special clerical concern. Records show that a large part of

the best land owned by the Greenlanders had gradually come into the possession of the

church."35 Norway eventually abandoned Greenland and it remained uninhabited, at least by

Europeans, for hundreds of years. The church played a key role in the process of recolonization

many years later. Europeans re-colonized Greenland with the help of the cleric Hans Egede,

who traveled from Copenhagen in 1721 to the island.

32

33

34

35

Fitzhugh and Ward, p. 176.

Logan, p. 77.

Fitzhugh and Ward, p. 97.

Fitzhugh and Ward, p. 12.

177

Unlike Iceland and Greenland, people were living in North America when the Vikings

arrived. The people living there also changed over time as the climate changed. The Thules,

ancestors of today’s Inuits, began move eastward from the Bering Sea in Alaska. The fortuitous

climate played an inviting role to many peoples. "The Norse arrived in the new world in A.D.

1000, a time of diverse social and political landscapes for the peoples living on the western

shores of the North Atlantic. Members of several different ethnic groups -- the Dorset people of

the eastern Canadian Arctic and northern Greenland, the ancestors of the Labrador Innu, the

Newfoundland Beothuk, and the Maliseet and Micmac of the southern Gulf of Saint Lawrence

and Nova Scotia -- had divided this territory into a multicultural region of discrete homelands

where their ancestors lived for many generations. After A.D. 1200 and during the height of the

warming, the Thule-ancestors of the Inuit---would also arrive on the scene."36

The Dorsets, in turn, had displaced Maritime Archaic peoples, the latter who had been

there since 6,000 BC. It is also possible they interacted with Algonquin peoples who generally

lived south of the Saint Lawrence River. The Thule displaced the Dorsets under similar

conditions to the conflicts with the Norse: they had superior technology for surviving in the

environment. "Armed with lances and with bows powered by a cable of twisted sinew, as well

as with warlike traditions developed in the large competing communities of coastal Alaska, such

a band of warriors would have been a formidable enemy. They could have easily displaced the

small and poorly armed communities of Dorset people from prime hunting localities, forcing

them to retreat to more marginal areas." 37 By the period 1200-1400 AD, the Inuit began to

replace the older Dorset culture that had arrived earlier.

36

37

Fitzhugh and Ward, p. 193.

Fitzhugh and Ward, p. 243.

178

The Norsemen encountered both peoples known as Native Americans and Eskimos. The

Eskimos came to North America during the 11th century, much later than the Native Americans

did. The Native Americans were "probably Beothuk, related to the Algonquians who occupied

the coastal regions of Newfoundland during the summer, fishing and hunting sea mammals and

birds - these would be puffins, gannets and related species - from birch bark canoes."38 The

Eskimos were of the Thule culture.

When the chance meeting of east and west took place, who was more surprised – the

Norse or the Inuit? The Norse had seen "Karelians" (Northeast Russia from the Karelian

Peninsula) or Laplanders in the Artic who were seemingly more Asiatic in ancestry. The Native

American, however, had probably never encountered anyone like these tall, blond, blue-eyed

people. The Norse military technology was somewhat superior to those of the Native

Americans.39 However, there is clear evidence of trade between the two. Norse products wound

up in the hands of the Native Americans with the appearance of metal arrowhead points

sometime replacing stone.40

By 1350, the Vikings abandoned the Western settlement of Greenland, which the

Skraeling or Eskimos soon took over, and retreated to the Eastern Settlement. The Vikings

survived until 1500 where the Skraelings killed off most of the Norse Greenlanders, save for a

few they kept as few slaves.

The plague was a consequence of trade. It was also a vehicle for introducing disease and

illness by bringing eco-environmental systems into a relationship. “Between 1339 and 1351 AD,

a pandemic of plague traveled from China to Europe, known in Western history as The Black

38

39

40

Wahlgren, p. 16.

Fitzhugh and Ward, p. 11.

Fitzhugh and Ward, p. 21.

179

Death. Carried by rats and fleas along the Silk Road Caravan routes and Spice trading sea

routes, the Black Death reached the Mediterranean Basin in 1347, and was rapidly carried

throughout Europe from what was then the center of European trade.”41 The plague hit Viking

settlements in Greenland and this had a direct impact on its ability to expand. By 1351, 25 to 50

percent of Europe people were dead, as well as the Middle East and south and East Asia.42

Theories of contact and migration to the Americas are undergoing a fundamental

revision. Rather than a single entry point through the Bering Straits, it is now believed that there

were probably multiple sources of migration in populating the hemisphere.43 In addition, some

see the meeting of peoples as an important event. "Thanks to recent advances in archaeology,

history and natural sciences, the Norse discoveries in the North Atlantic can now be seen as the

first step in the process by which human populations became reconnected into a single global

system. After two million years of cultural diversification and cultural dispersal, humanity has

finally come full circle."44

c.

A Modern Case of Climate Change: Conflict between Fulani and Zarma and the Role of

Desertification

Time

Class

Category

Modern

Environmental Breadth

General Resources

Richard Thomas, “The Role of Trade in Transmitting the Black Death”, TED Case

Studies, No. 414, May 1997, p. 1, http://www.american.edu/TED/bubonic.htm.

42

Gottfried, Robert. The Black Death: Natural and Human Disaster in Medieval Europe,

New York, Free Press, 1983.

43

Fitzhugh and Ward, p. 11.

44

Fitzhugh and Ward, p. 12.

41

180

Type

Climate Change

Climate change is an ongoing factor in the relationship between environment and

conflict. It was largely responsible for the war that lasted for 20,000 years or more between

Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. Climate change was an essential element in the later conflict

between European Vikings and Native Americans in North America.

Climate change creates new ecotones or areas of habitation by differing groups with

differing technologies and economic subsistence patterns. The conflict in Niger is a classic case

of ecotone shift. The Sahara desert, the largest arid area on the planet, moves periodically in a

north-south line and has so over millennia. This ebb and flow of desertification brought differing

people into confrontation. This line between habitable and inhabitable moves not only through

Niger, but also the countries of Ethiopia, Somalia, Chad, Nigeria, Niger, Mauritania, Chad,

Sudan and other parts of Africa (see Figure IV-3).

Climate change today is magnified with the precarious balances between environmental

supply and demand in some parts of the modern world. This is especially the case in Africa.

There are changes in long-term cycles, as was the case with the end of the last Ice Age 50,000

years ago. These long-term cycles may involve changes in ecotones that involve large portions

of the planet. There are also shorter ecotones that occur, such as the cooling in the North

Hemisphere in the 1500-1700 AD Period. Climate and weather conditions in fragile zones over

the short-term can have extreme consequences for inhabitants used to seasonal and yearly

migration patterns.

Climate change is decomposable by time and geography. There are long-term climate

patterns but there are also shorter-term patterns that people ordinarily refer to as “weather”.

Weather is the cycles of climate change limited to the lifespan of an individual and perhaps some

181

stories from parents and grandparents, or perhaps a span of 100 years. Within certain climates

and micro-climates changes in weather can be significant over the short-term.

Figure IV-3

Africa and the Approximate Limit of the Sahara and the Beginning of the Sahel

182

The southward drift of the Sahel during a dry period pushed Fulani tribe nomadic herders

south towards greener pastures. Unfortunately, this encroached on lands of the Zarma, who were

sedentary agriculturalists. These two groups clashed over diminishing pasture and water

resources for economic and food subsistence.

In 1997 in Niger seven people were killed and 43 wounded in separate clashes between

Fulani herders and Zarma farmers in the sectors Téra and Birni N'Gaouré. State radio (La Voix

du Sahel) reported seven deaths occurred near the village of Falmaye (Birni N'Gaouré), southeast

of the capital Niamey.45 Zarma villagers allegedly attacked a Fulani camp, seeking revenge for

the death of a Zarma in an earlier fight with Fulani herders. At least three of the victims were

burned to death inside their straw huts. Later, there was fighting between Fulani herders and

Zarma farmers in the Téra region, northwest of Niamey. There were no deaths, but 35 people

were wounded, 19 seriously.46

The problem spread beyond Niger. “Water comes next to grazing land in importance

among the pastoralists in Nigeria. The Fulani see the provision of water as an antidote against

the predicaments of marginal environment.” Water rights accrue to the people who “dig the

well, make a path to it, or rid the site of predator animals and harmful objects.”47 Sedentary

groups do not recognize these rights.

Niger’s people have dealt with climate change in both the short and the long term. In

ancient times the climate in Niger was temperate. “During the Holocene period of the past

10,000 years there was a ‘warm’ climatic optimum roughly 5,000 years ago. At that time, more

See Andrew H. Furber, “Desertification in Niger”, ICE Case Study Number 29, June,

1997, Case Name: NIGER. http://www.american.edu/TED/ice/niger.htm.

46

Mayer, Joel, ed. "Ethnic Violence Kills Seven." Source: AFP via Camel Express

Telematique. May 16, 1997. Available http://www.txdirect.net/~jmayer/cet.html (online).

47

“Scarcity of Water as an Impediment to Pastoral Fulani Development”, Ismail Iro,

http://www.gamji.com/fulani6.htm. Accessed January 5, 2006.

45

183

humid conditions generally were markedly contracted. Lakes existed even in parts of the central

Sahara. The current state of climate was reached roughly 3,000 years ago.”48

The movement of the Sahel shows alternating patterns of global warming in the middleterm. “Observational records show the continent of Africa is warmer than it was 100 years

ago…The 5 warmest years in Africa have all occurred since 1988, with 1988 and 1995 the

warmest years. This rate of warming is not dissimilar to that experienced globally, and the

periods of the most warming – the 1910s to the 1930s and the post-`1970s --- occur

simultaneously in Africa and the world.” Africa’s precipitation patterns also show longer-term

variations. The period 1800-50 was relatively dry, similar to today, 1850-1895 was much wetter

and then another drier period ensued.49

Several diverse ethnic groups in Niger live in three different climactic zones in Niger.

The three zones are divided by latitude and degree of intersection with the Sahara. The northern

part of the country is the Sahara desert. To the south is a transition zone (the Sahel)

characterized by a combination of desert and scrub. Nomads and sedentary groups inhabit the

Sahel. Herding and animal husbandry characterize the livelihood of nomads. As animal stocks

increase, grazing demands on the fragile ecosystem near the desert exhaust grassland supplies.

These extra stresses on the vegetation, in addition to the changes in climate, can heighten

impacts.

The Zarma are farmers who live in the Sahel. They live primarily in Western Niger, but

there are also some pockets in Burkina Faso and Nigeria. The Zarma grow subsistence crops,

IPCC, “Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, 10.2.3.3.

Paleoclimate of Africa,” Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change,

http://www.ipcc.ch/pub/tar/wg2/381.htm, accessed May 5, 2002.

49

IPCC, “Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, 10.2.3.3.

Paleoclimate of Africa,” Integovernmental Panel on Climate Change,

http://www.ipcc.ch/pub/tar/wg2/381.htm, accessed May 5, 2002.

48

184

such as millet, sorghum, rice, corn and tobacco and cash crops, such as cotton and peanuts. This

production mode requires some irrigation.

Milk is an important part of their diet and culture of both the Zarma and Fulani. The

Zarma own cattle, but it is the Fulani or Tuareg people who tend the animals. This complex

rental system is an outcome of both economy and culture. When mature, cattle are driven to

coastal cities of West Africa for processing and trade. The Zarma were once skilled with horses,

but this skill has been lost. They now specialize in raising cattle.50

Animal husbandry remains one on the main economic activities of Niger. Livestock

products include cattle sheep goats and dromedaries. The Fulani, also called Peul or Fulbe, are a

primarily Muslim people found in many parts of West Africa, ranging from Lake Chad to the

Atlantic coast, with concentrations in Nigeria, Mali, Guinea, Cameroon, Senegal, and Niger.

The typical Fulani are nomads, but after many years of integration with other cultures, and the

depletion of their herds to environmental conditions, they now rely on farming for livelihood.

The nomads make temporary camps of portable huts, exchanging dairy produce for cereal foods.

The Fulani rarely kill cattle for meat. “Because animals need water, the demand for it among the

Fulani exceeds that of the rural people.”51

Archeologists believe there is a tendency of the Sahara desert to “move” according to a

prescribed model -- the pulse model -- and result in waves oscillating over thousands of years,

leaving socio-economic impacts on the peoples living in its path. Archeologists found evidence

of social clusters of communities that are grouped around Timbuktu but were not an integrated

community. Archaeological findings combined with geological dating techniques suggest a

50

"Zarma." Encyclopedia Britannica. Internet Search June, 1997, http://bastion.eb.com.

“Scarcity of Water as an Impediment to Pastoral Fulani Development”, Ismail Iro,

http://www.gamji.com/fulani6.htm

51

185

"pulse" pattern to Sahara desertification. Every time a pulse period occurred, settled societies

were uprooted.

Research shows pulses of climate and weather changes occurring 10,000 years ago.

Oscillations correspond to apparent changes in the archeological findings and societal identity of

Late Stone Age people. The longer a community stays in one place, the more sedentary it

becomes. The more sedentary the society the more traditions it develops. When forced to move,

traditions are upset or lost and specialization diminishes.

Today, there are a declining number of "microenvironments" that provide for safe haven

during periods of weather shifts. French colonization of Niger in the 1920's led to an increase in

grazing intensity and cash crop intensity in the Sahel. Change in the use of the environment

effectively initiated a socio-economic correlation between human impact and desertification.

Niger's agricultural policy is to achieve food self-sufficiency regardless of climate

changes. There are several alternatives, including dry-cropping in rural areas; hydro-agricultural

projects including the use of depressions and water-points to increase cultivation; and soil needs

that apply nitrogen based fertilizers and manure.

There is some recognition of problems caused by small-scale climate change and efforts

to react to these problems. “Over 300 representatives of national, international, and nongovernmental organizations have expressed today full commitment to support Niger’s

Programme to combat desertification and drought. Participants at the First National Forum to

Validate the National Action Programme to Combat Desertification and Drought (6-8

September), evaluated and finalized the document presented by the National Council on

Environment and Sustainable Development, that coordinated consultations since 1995.”52

52

Niamey, 8 September 2000, UNCCD, www.unccd.org.

186

There have been attempts at conflict resolution. “The positive aspects of water extraction

include cooperation between the Fulani and the farmers. Mutual benefits accrue when the

farmers agree to let the Fulani use the water facilities in exchange for milk or dung.” Sometimes

these efforts also fail. “It is not uncommon to find the competing groups or individuals going to

the extreme of sabotaging the very public water supplies, so as to monopolize the facility.”53

The Niger government and multilateral aid agencies have been attempting to increase

water supplies (small dams and deeper wells, for example) but some warn that the increase in

water without the increase in grazing land is a recipe for disaster.” More water attracts more

farmers to the arid lands of the Fulani. “Fulani herdsmen around the Tiga Lake and the Kainij

Dam in northern Nigeria complain against transient farmers who are building permanent camps

around the marshy areas and taking way the grazing land.”54

Is desertification in part a result or a consequence of cultural and subsistence practices?

Some point to the long-standing cultural practices as a problem. Fees required to keep facilities

operating are usually ignored because of favoritism to kin or a basic belief in the sharing of the

resource. Bribery is quite common in obtaining water.

Some blame government policies for the conflict because recognition of Fulani water

needs is a recent event. Others blame government policies for unintended consequences.

Irrigation and water diversion projects centralize water demand, usually at the expense of the

pastoralists. This will also disadvantage wildlife or domestic animals. The competition extends

not only to water but also to the grazing lands nearby.”55

53

54

55

“Scarcity of Watert”, Ismail Iro.

“Scarcity of Water”, Ismail Iro.

“Scarcity of Water”, Ismail Iro.

187

d.

Comparing and Reflecting on the Climate Cases

There will be more focus on climate change cases in the future. Today there appears to

be a relatively high rate of climate change, with people being in part responsible. Climate

change impacts people most rooted in the environment and in low-level technological means of

subsistence. These are often aboriginal peoples.

Aboriginal (or original) peoples constitute a general term indicating humans who were

the original inhabitants of a place. Aboriginal people, generally and specifically, survive in

small pockets in many countries. There is some irony in that the oldest people in the place are

the most impacted by changes in climate. It is the rapid pace of change which has created this

situation.

In the “ancient cases”, the climate change case focused on the historic conflict between

humans and Neanderthals that was the result of significant changes in climate extended over

extremely long time periods. This was largely the result of the pull factor. The end of the Ice

Age brought on an expanded ecotone that invited conflict between competing, though related,

species. Humans proved more adept than Neanderthals at changing with the evolution of the

climate. The physical re-alignment also requires a social re-alignment, which is then a source of

conflict.

A slight change in history might have created a different view on environment and

conflict among human species. Aboriginal peoples in Australia, Native Americans in North

America, and the Ainu (a Caucasian people living on the island of Hokkaido in Japan) have often

survived because of their isolation. What if a small population of Neanderthals survived?

188

Imagine if Neanderthals had been able to establish a stronghold in an isolated part of

Siberia and learn some of the human technologies they no doubt encountered. It is thought that

Neanderthal weapons were incapable of killing a mammoth, and this was a great advantage for

the humans, especially weapons such as the Clovis-point spear. Perhaps if the Neanderthal

survived in this area under their control, so too would the mammoths. Eventually, Neanderthal

technology would have advanced.

Perhaps the Ice Age lasted somewhat longer or a disease set back human advance.

Perhaps over time Neanderthals might have adopted some basic human tool and agricultural

technologies. Siberia has been relatively unpopulated until modern times. For millennia,

Neanderthals would have faced limited contact all but Aboriginal Sinoid peoples. As Russia

grew as a nation and spread east towards Vladivostok, the tsar’s troops would have encountered

them and would no doubt be militarily superior.

After a few violent encounters in which the Neanderthals would lose badly, they may

send a representative to sue for peace and the Neanderthal’s swore allegiance to the tsar. The

Neanderthals would begin learning more from humans and began moving out of their

autonomous region to other parts of Russia. They would eventually learn to wear modern

clothes and groom by modern standards.

The Neanderthals might have been protected under the Communist rule which may have

regarded them as the ultimate proletariat. When the Soviet Union broke up, the region like

others could declare independence. The country of perhaps “Neanderthalia” would emerge and

seek admittance to the United Nations.

Current discussion about climate change and the potential for conflict is set on the time

horizon of decades. Many researchers acknowledge this is an insufficient time horizon for

189

analysis. The role of climate change in the Viking story is an epic that stretched out over 500

years. This case certainly gives pause to conceiving of such problems over time and the range of

impacts and complexities that occur along the way. Such a focus on mega-trends of environment

and conflict interaction also becomes more complex. This complexity has a multi-disciplinary

flavor and involves considerable feedback between the differing parts of the complexity.

Micro-trends will have less of this complexity and breadth and tend to focus on a small

set of key variables. Such problems are decomposable or related to other problems. That is, key

cases of environment and conflict can be grouped by the time horizon of the problem, especially

if we start from a mega-trend issues that spans 500 years. First, as the findings indicate, there

were macro-level climate changes trends even within that larger period, that could be broken

down into cycles of 100, 50 or even 25 years.

Second, the macro-level changes in climate no doubt included many micro-level impacts

where the differential impact would reveal differing implications for humans. These impacts can

be either beneficial or detrimental in terms of human subsistence and economic value. For

example, warmer weather in Greenland no doubt meant more trees could grow, which is a

benefit as a key building and fuel material. On the other hand, warmer weather may well have

caused the walrus to move further north, since it enjoys the colder weather, and no longer

available as a food source. There movement would remove a potential food source and force

social and technological change.

In the end, the Vikings had little impact on the course of events in North America. With

the exception of some limited technology transfer, the epochal meetings of these two peoples, the

uniting of humanity once again, the actual connection of east to west would take another 500

years to really compete. “In summary, the Norse Sagas indicate that the Aboriginal People

190

whom the Vikings met in Vinland wished to trade, but that violence ensued as a result of Norse

attacks. There is no evidence that the Norse had any recognizable effect on the aboriginal groups

they encountered in Newfoundland and Labrador. The Vikings were simply too few to deal with

the people who resisted the invasion for their homeland. Non-metal weaponry was not

significantly superior to the arrows that used stone.”56

Imagine if events had been different. When the Vikings came to Newfoundland, the

weather was warmer and was not to turn cold until several hundred years later. There was ample

time to move further south, to build up systems of transportation, food production and

infrastructure, and to survive the mini-Ice Age around 1500. At that time, Europe’s population

was rapidly growing, and their level of technology was increasing.

At this time, the military technology of the two was about the same. This technological

growth is evident from the disparity in military technology at the time of Columbus between the

two. “The Vikings looked pretty fierce but they really had no technological advantage at all in

military terms.” 57 All of this suggests that the Vikings needed new waves of emigrants to

sustain their colonies.

Europe too was weakened by the Dark Ages and the Plague. It took several hundred

years but Europeans populations recovered and technology started to become ascendant in the

society. “By the 14th Century, things had changed. Due to technological innovations in

agriculture, such as the three-field planting system, the population of Europe had risen to a level

that it had not seen in millennia, during the Roman Empire. This growth is despite the "Little Ice

56

Kevin McAleese, ed., Full Circle, St. Johns, Newfoundland, Newfoundland Museum,

2000, p. 47.

57

Kevin McAleese, ed., Full Circle, p. 21.

191

Age," a period of climactic deterioration and generally colder weather, which would not end

until the mid-18th Century.”58

“The irony about the fate of the Greenland Vikings is that if they could just have hung on

for another 80 years, they would have probably been all right.” 59 European technology,

especially military, made enormous advances in this period and this technology would naturally

“escape” to them from other Europeans. Their linkage to this group of nations who were

undergoing a Renaissance of change would have given them an enormous advantage over the

native peoples of North America. This advantage would have become clear long before 1492.

Viking expansion may have advanced down the eastern sea board of the United States and

voyages to South America would not be out of the question.

The development of a Norse society in North America in the year 1000 could have

produced a different history. An influx of settlers armed with these new technologies would

have created Norse colonies of culture and life style, somewhat of a cross between the Old and

New Europeans. Imagine a series of Norse colonies along the east coast of North America

already in place when Columbus arrived to the south. If things were only slightly different, the

United States and Canada might be speaking Norwegian or Swedish today.

The conflict with the Neanderthals was a global cycle of climate change that spanned

perhaps at least 10,000 years. The Viking expansion and contraction occurred within a smaller

scope of change and thus a smaller cycle of history, perhaps 500 years. This case of the shift in

the Sahel is an even smaller cycle of perhaps 20 years. This telescoping of the event (in the

number of years it takes) and matching it to the consequence (the changes to an area and the

58

59

Gottfried.

Kevin McAleese, ed., Full Circle, p. 27.

192

people in it as a result) can be a useful lens from which to judge a variety of environment and

conflict issues

These “modern cases” evoke issues that have roots in thousands of years of conflict

between human beings over resources. Whether it is general conflict, resource conflict, or used

to wage war, the environment is a constantly recurring theme. A similar case involves the

Tuareg in a region near the Fulani-Zarma dispute.60 They came into conflict with a farming

people, the Gada koi, who were supported by the government of Mali.

The Fulani live in the Sahel but the Tuareg live in the even drier climate of the Sahara.

The Tuareg, a people related to the Berbers, played an important historic role as traders between

Arab and African worlds, but also were pastoralists. Tuareg independence was only lost to the

French in Mali and Niger in the late 19th and early 20th century. Land reform programs in Mail

in the 1960s encroached on traditional Tuareg lands and a guerilla war ensured with a severe

government reaction. Many Tuareg fled to other parts of the Sahara. A peace treaty was signed

in 1991 and violence generally stopped around 1996.

A drought -- a seeming contradiction in a dry land -- between 1968 and 1974 worsened

the situation for the Tuareg. Over-grazing of fragile Sahel lands exacerbated the problem.

Animosity continued to simmer and conflict broke out again in the early 1990s. The patterns are

periodic in nature, and related to the “harmattan”, a period from May to September that brings

strong winds that move sand and lead to soil erosion.

2.

Arable Land

Ann Hershkowitz, “The Tuareg in Mali and Niger: The Role of Desertification in Violent

Conflict “, ICE Case Studies, Number 151, August 2005.

http://www.american.edu/ted/ice/tuareg.htm.

60

193

Arable land has been in great demand since the Agricultural Revolution. The cases of the

abandonment of Mohenjo-Daro, the decline of the Mayan Empire and the genocide in Rwanda

reveal instances over time where the struggle for control of arable land was exacerbated by

ethnic and sectarian strife.

Arable land cases fall under the attribute “territory” is the context of the conflict link in

the ICE data base. The arable land cases have a significant relational factor and are part of longstanding tension. The causal representation of these cases is best represented by the red loop in

the conflict sub-system. The dominance of the stalemate outcome in this loop is extremely

central to behavior. The stalemate is intrusive because it lasts an extremely long period and

revolves around long-standing territorial disputes.

The disputes are accompanied by demographic shifts that gradually increase the tension

in the cases as the arable land resources become limited. These cases are more medium term in

duration, focused on tropical habitats and changes in them, and involve demarcation of border

issues. This variable also has a key role in the environment sub-system noted in the causal

system (refer back to Figure III-1 and Figure III-2). This loop of causality includes border

conflict issues, temperate areas, and stalemate outcomes.

194

Figure IV-4

Arable Land Causal System (the Red Loop in the Conflict Sub-System)

a.

Mohenjo-Daro’s Decline, the Loss of Arable Land and Aryan Invasions

Time Period

Class

Category

Type

Ancient

Environmental Breadth

General Resources

Climate Change

The end of the Ice Age and the extraordinary period of global warming about 10,000

years ago produced social impacts in South Asia, as it had in other parts of the world. As in the

Middle East, “the melting of ice from the snow capped peaks of the Himalayas began ten

195

thousand years ago. The trickling flow of clean and pure water merged into streams and currents

and turned into confluence of streams that turned into rivers flowing down the slopes into the

plains of northwest India. The fertile area came to be other “edens” that emerged with early

urban settlement patterns along the banks of lush and fertile rivers. This is especially true in

South Asia where the Saraswati, Indus, Yamuna, Ravi, Beas, Sutlej, and Ganges are a few rivers

that can be named as having formed out of this melting of ice caps.”61 (This was also the case in

the Middle East.) As the ice receded, humans advanced.

“With the ending of the Ice Age, around 10,000 years ago, Himalayan glaciers melted

and flowed into the rivers of South Asia. One recipient was the Saraswati River, now a lost river

that at one time supported many early city-states. Due to earthquakes and great floods it changed

its course over six times.” With the end of glacier melt and a drying climate the river began to

dry up and no longer flowed into the Arabian Sea. The many cities that developed along the

river eventually expired. The only cities to develop outside of this region were Harappa and

Mohenjo-daro. 62

From 8,000 BC, the Mesolithic age began and spread into the Indian sub-continent

around 4,000 BC. During this time, hunters used sharp and pointed tools for hunting and killing

fast-moving animals. The beginning of plant cultivation appeared. The Chotanagpur Plateau,