Prevention of Postnatal Depression A Health - HPH

advertisement

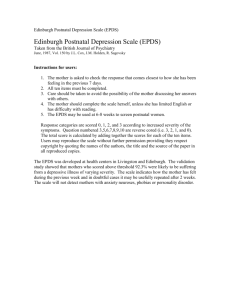

Prevention of Postnatal Depression: A Health promotion issue Introduction: It is well documented that 10-15% of women experience postnatal depression (PND) in the first year following childbirth (Cooper et al, 1988, O’Hara et al, 1989). The severity of the illness varies greatly and the effects of the illness can cause problems throughout the family unit (Lovestone and Kumar, 1993). Where symptoms are not detected or go untreated, a woman’s mental health can be severely affected, as can the marital / partner relationship. Fifty per cent of spouses suffer concurrent mental illness, usually depression (Forman et al, 1992; Lovestone and Kumar, 1993). By definition postnatal depression impairs the mother in her daily life. Often this means that her relationship with her baby will be affected. A profile of mother-infant disturbance in the context of postnatal depression has emerged, with affected parenting manifested in either a withdrawn, disengaged parenting style or an intrusive, hostile one. The importance of detecting and responding to these cases is underlined by the growing knowledge of adverse effects on the psychological, cognitive and intellectual development of the children (Murray and Cooper, 1997, Sharp et al.1995 and Hay et al.2001.) In the ‘Why Mothers Die’ report of 1997-1999 suicide accounts for 10% of maternal deaths, and the report suggests that, if a large number of unreported deaths from psychiatric causes were taken into account, it would be the leading cause of maternal mortality (Royal College of Obst. and Gynaec.). Screening and prediction of Postnatal Depression: Research conducted in the Rotunda Hospital in Dublin in 2,000 found that 13.4% of women suffered from PND by six weeks post partum. The research found that women who subsequently developed PND could be identified prior to discharge from hospital by eliciting a history of depression, combined with a positive score on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Crotty F.,Sheehan J.). The EPDS is a self-report tenitem scale designed by Cox et all (1987). It is validated and reliable and is used internationally. It has a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 78% at a cut-off of equal to or above 12. In order to increase awareness of Postnatal Depression, routine screening using the EPDS is offered to delivered mothers prior to discharge from the Rotunda Hospital. Following completion of the EPDS women with a positive score are given the chance to discuss their feelings and plan appropriate support from family, friends and professionals in the community or the hospital as appropriate. An information booklet is also given to all mothers, with advice to read it with their partners so they can then plan preventive strategies together. Advantages of screening in Maternity Hospital The psychological care of postnatal women is currently haphazard in the Irish Healthcare setting. For their six-week postnatal check-up women may attend the Maternity Hospital, Consultant Obstretrician, GP or may not attend anyplace. The EPDS is acceptable to both mothers and staff with over eighty percent of women returning the completed questionnaire in the Rotunda Hospital. In a study by Murray and Carothers (1990) over ninety seven percent returned the questionnaire. Mauthner (1997) found that the greatest difficulty the mothers faced was admitting their feelings and difficulties. The EPDS is the ideal tool to help open the subject. Encouragement to talk about their feelings in the early postnatal period may help prevent later emotional problems from developing. Helping women to recognise their own needs, and to believe that those are valid, can empower them to seek help. Low mood is often seen as added workload or tiredness by mothers rather than depression (Small, 1994). Women who do realise they need help may be unable to organise themselves to make an appointment. Most women with PND do not require psychiatric intervention. The reassurance of a supportive professional may be sufficient (Holden J.,1991). Holden also states that a high percentage of women commented that it had been a relief to be asked about their feelings. Completing the questionnaire only takes minutes. The decision to reveal their feelings to a Health Professional is one that any individual must be free to make for themselves. They must be reassured that it is safe to do so and that help is available without her having to ask for it. Some mothers may be afraid if they confide the extent of their distress they may be labeled mentally ill or fear that the baby may be taken into care. These concerns are addressed at the time of screening and a follow-up supportive service offered to women who wish to avail of it. Conclusion Respecting women’s individual needs and responses, involving them in their own care, creating a climate in which they, their partners and their caregivers feel free to discuss the emotional and practical implications of parenthood are important steps towards promoting the psychological wellbeing of childbearing women and the future generation. (Holden,1991) Clearly, the emotional disturbance associated with postnatal depression underlines the need for prompt and cost-effective management. The Rotunda Hospital initiative is increasing awareness and detection of PND and consequently preventing many serious adverse outcomes. References Cooper PJ, Campbell EA, Day A et al (1988) Non-psychiatric disorder after birth: A prospective study of prevalence, incidence, course and nature. British Journal of Psychiatry, 799-806. Cox JL (1986) Postnatal depression; A guide for health professionals. Edinburgh; Churchill Livingstone. Cox, J.L., Holden, J. M. and Sagovsky, R. (1987) Detection of Postnatal Depression: development of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 782-786. Crotty F and Sheehan J (2000) Prevalence and detection of postnatal depression in an Irish community sample. Submitted to British Journal of Psychiatry. Foreman, D, Hackney M and Cox J (1992) The impact of postnatal depression on new infants and older siblings. (Conference Paper). Edinburgh; Marce Society. Hay, D., Pawlby S., Sharp, D., Asten, P., Mills, A., Kumar, R., (2001) Intellectual problems shown by 11year-old children whose mothers had postnatal depression. J. Child Psychiatry Vol.42, No.7 pp.871-889. Holden, J., and (1991) Postnatal depression: Its nature, effects, and identification using the EPDS. Birth 18:4, pp211-221 Lovestone S and Kumar R (1993) Postnatal psychiatric illness; the impact on partners. British Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 210-216. Mauthner NS (1997) Postnatal depression; how can midwives help? Midwifery (1997) 163-171. Murray, L., Carothers, AD. (1990) Estimating psych. Morbidity by logistic regression: application to postnatal depression in a community sample. Psychol. Med., 20: 675-702. Murray L and Cooper PJ (1997) Effects of postnatal depression on infant development. Arch Dis Child. 1997,77; 99-101. O’Hara MW, Zekoski EM, Phillips LH et al (1989) A controlled study of postpartum mood disorders; comparison of childbearing women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2001) Why mothers die 1997-1999; the fifth report of the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. London; RCOG. Sharp, D., Hay, D., Pawlby, S., Schmucker, G., Allen, H., Kumar, R., (1995). The impact of postnatal depression on boys intellectual development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 36, 1315-1336. Small R., Astbury J, Brown S et al. (1994) Depression after childbirth: does social context matter? The Medical Journal of Australia 161: 473-477.