Breathing Part II

Getting Technical

Breathing Part II

Inhalation and Exhalation

On the face of it, inhalation and exhalation is the most natural thing in the world. The trouble is that as soon as we pick up our respective ‘pieces of plumbing’, other factors can sabotage the most basic instinct.

Baring in mind the importance of a natural posture, as discussed in the last issue, volume and efficient generation of the very 'fuel' that drives our instruments is crucial to success. Many players frequently experience difficulties with the embouchure when over compensating for disorganized and shallow breathing, which simply can't fully sustain melodic phrases. Sufficient and efficient breathing for brass players should be approached with athletic enthusiasm, establishing a feeling that too much breath is probably better than too little. In the same way that a sculptor refines a large piece of raw material, a brass player can far more easily refine over energetic breathing than deal with the side effects of unnecessary contortions and resultant tension which is often heaped upon the embouchure. In my opinion, the embouchure very definitely has a

‘shelf life’ and we should do all in or power to conserve its

muscular structure by combining regular (never obsessive), judicious practice with the maximisation of breath support. In other words, the larger and stronger abdominal muscles used in breathing deliver air to relatively small and delicate muscles of the embouchure. The secret is found, therefore, when one achieves perfect integration by developing lung capacity and a vigorous approach but without disturbing the intellectual trains of thought and the rest of one’s playing functions.

The danger with untutored ‘energetic inhalation’ is that it usually creates unwanted tension in the form of raised shoulders and a constricted throat, resulting in a similarly thin and unsatisfying tone and barely enough air to sustain a moderate phrase. The Yoga expert, Swami Sivananda refers to this as Clavicular breathing.

According to Sivananda there are three types of respiration which when combined produce full yogic breathing.

‘Most people use only a fraction of their lung capacity for breathing. They breathe shallowly, barely expanding the ribcage. Their shoulders are hunched, they have painful tension in the upper back and neck and they suffer from lack of oxygen’

. Sivananda goes on to list the three kinds of breathing as:

Clavicular – shallow with shoulders and collarbone raised, abdomen contracted during inhalation with maximum effort for a

minimum amount of air.

Thoracic – expanding rib cage.

Diaphragmatic - deep abdominal breathing, taking air to the lowest part of the lungs.

On it’s own then, Clavicular breathing is clearly undesirable, however, when used in conjunction with the other two types of breathing the result is that the chest cavity expands forwards rather than upwards and the shoulders and neck remain relaxed. In order to maximise capacity players can, therefore, utilize all three methods (in reverse order), producing a three stage breath and thus inflating the abdomen rather like filling a jug……from the bottom up. The eminent Bass Trombonist and teacher, Ben Van Dijk puts forward a most concise three stage inhalation system in line with

Yogic thinking in his book, Ben’s Basics.

Contraction of the diaphragm filling the lower lungs

Movement of intercostals - the middle lungs

Upper chest expansion, the lower abdomen being very slightly drawn in, giving lungs support.

At this stage I hope readers will agree that I am, at the very least, fulfilling the title of this ‘Getting Technical’ column, which in turn leads on to one of the most contentious issues in the world of

instruction. Terminology, when attempting to describe technical advice, is interpreted in many ways by different people.

Although our assumption is that efficient breathing is the key to success as a brass player, the somewhat uneducated guesswork of past generations has often created confusion over a relatively simple act. Conseaquently, the popularity of trombone study, especially in higher education programmes has inspired teachers and performers to engage in exhaustive research in this area, often correcting mistaken beliefs with sometimes complex but never the less accurate refinements. Choosing phrases appropriate to universal understanding is, therefore, crucial to instruction, referring to inhalation as a fundamental survival instinct, invoked simply by ‘yawning’ together with phrases such as ‘breathe to expand your body’

, can in certain circumstances achieve comprehension without the complex terminology referred to above. The phenomenon of the cough or the sneeze can also provide interesting analogies and usefully generate up to eight pounds of pressure per square inch, while the cough alone helps to focus attention on the diaphragm muscle and consequently initiate exhalation. Even a ‘gasp’, the human reaction to shock, is an ideal way to demonstrate natural inhalation.

All of the above usually occur from a state of relaxation of the

lower abdominal muscles or as frequently described (incorrectly) as the stomach muscles . The use of the word stomach is confusing, given that this is really the place where food is digested and therefore cannot relax. However, this does illustrate that the use of certain analogies gain instant understanding, regardless of accuracy. The word ‘diaphragm’ alone is legendry in popular brass playing terminology and its use would seem to have been the sole answer to correct breathing in past eras.

‘Push from the diaphragm’, ‘support with the diaphragm’ and

‘stomach breathing’

are all physical impossibilities but never the less effective phrases in promoting physical awareness in this region.

In fact, as a muscle, the diaphragm can only contract and therefore, cannot push. This contraction compresses organs of the lower abdomen to create the vacuum. The relaxation of the diaphragm allows the organs to return thus pushing air up into the chest cavity. Additional use of the abdominal or intercostal muscles to assist this action can lead to a hernia. Indeed, in my own experience, the umbilical hernia is (and has been) a very common complaint among brass players and according to my Consultant

Surgeon is referred to as such in medical journals going back to the nineteenth century.

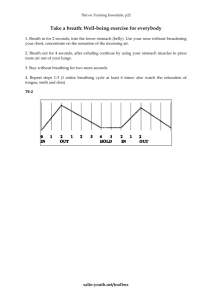

The words Inspiration and Expiration are frequently used as alternatives to Inhalation and Exhalation as in this diagram showing the passage of the diaphragm during a normal breath.

By expelling as much air as possible from your body one achieves the scientific phenomenon of the vacuum.

A ‘stabbing pain’ in the area of the diaphragm is often described as the signal at which one only has to open the mouth to experience the involuntary filling of the lungs and invoke natural inhalation. The breath at the beginning of a note or phrase is most effective when initiated from the point of vacuum through the oral cavity. Opening the throat and mouth and drawing in air to resemble a HAW shape and sound should prompt the throat to relax thus giving efficient and silent passage to the incoming air. With current sensitivity in recording techniques quiet inhalation is a prerequisite to any wind player.

Additional understanding can be achieved by describing the sensation of cold air making contact with the back of the throat.

Further strictly incorrect assumptions regarding the passage of the diaphragm include

‘pulling in and up’

(quite impossible) in order to gain abdominal firmness, provoking a tradition of older teachers to strike students in the abdomen to test for muscular rigidity.

These days a preferable and possibly more ‘ PC way’ to describe this might be to contract the diaphragm, which in turn pushes against the front abdominal walls thus creating the ‘sensation’ of firmness.

In the next issue I intend to round off the topic of breathing by investigating various ways of developing and improving breath control.

Further reading :

1) www.sivananda.org

2)

Ben’s Basics

BVD Music Productions 2004

3) Proper Breathing and Breath Control by

Jim Biddlecome ITA Journal July 1984