6.lung abscess

advertisement

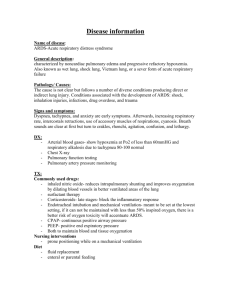

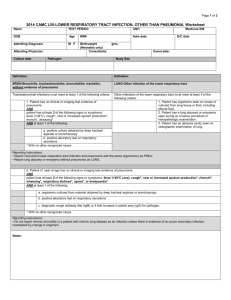

THE KURSK STATE MEDICAL UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF SURGICAL DISEASES № 1 LUNG ABSCESS Information for self-training of English-speaking students The chair of surgical diseases N 1 (Chair-head - prof. S.V.Ivanov) BY ASS. PROFESSOR I.S. IVANOV KURSK-2010 Anatomy The respiratory system consists of the nose, nasal passages, nasopharynx, larynx, trachea, bronchi, and lungs. The respiratory tree functions proximate to the thorax and its bony and muscular components as well as to the pleura, pleural cavity, and mediastinum. The influence of pathologic changes in associated structures on the function of the respiratory system is important, and one should be familiar with these anatomic relationships and the "topographic anatomy" of the thorax. Chest wall and pleura Beneath the skin and subcutaneous tissue, the chest wall is covered by the pectoralis muscles anteriorly, and posterolaterally the latissimus dorsi and serratus anterior muscles are encountered. In an anterior thoracotomy, the fibers of the pectoralis major may be split, exposing the intercostal muscles. However, in the standard posterolateral thoracotomy, the latissimus dorsi is divided, and then the serratus anterior is divided or split. Trachea The entrance to the trachea is guarded by the larynx. It functions to prevent aspiration and as the organ of phonation and has an important role in production of the cough. The mucous membrane lining of the larynx is covered by ciliated epithelial cells and a few goblet cells. The epithelial surfaces in contact with food are covered by stratified squamous epithelium. Except for the cricothyroid muscle, which is innervated by the external laryngeal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve, the larynx receives both motor and sensory innervation by way of the vagal accessory complex of nerve fibers. The intrinsic muscles of the larynx receive their motor innervation by way of the inferior laryngeal branch of the recurrent vagus nerve. The trachea is a fibromuscular tube 10 to 12 cm. in length and varying from 13 to 22 mm. in width, supported laterally and ventrally by approximately 20 Ushaped hyaline cartilages. The trachea originates at the level of the cricoid cartilage and descends through the superior aperture of the thorax and the superior mediastinum to its bifurcation at the level of the stemal angle (lower border of the fourth thoracic vertebra). Bronchi At its termination, the trachea divides into the right and left principal bronchi. The right bronchus is 12 to 16 mm. in diameter; the left, 10 to 14 mm. The combined cross-sectional area exceeds that of the trachea. The right main bronchus deviates less from the axis of the trachea than does the left; this explains why foreign objects entering the trachea more often lodge in the right bronchus or one of its branches. Within a primary lobe, the secondary bronchus soon divides into ternary branches, which are remarkably constant in number and distribution. Lung abscess Lung abscess: A localized cavity with pus, resulting from necrosis of lung tissue, with surrounding pneumonitis. A lung abscess may be putrid (due to anaerobic bacteria) or nonputrid (due to anaerobes or aerobes). "Gangrene of the lung" denotes a similar though more diffuse and extensive process in which necrosis predominates. Classifications Etiology: Aerobic Anaerobic Mixed 2. Not bacterial The elementary organisms Funguses Pathogenesis 1. Bronchogenic With aspiration With obtiration Metapneumonic 2. Hematogenous (embolic). 3 Traumatic 4. Lymphogenous. 5. Contact. Localization: 1 Central 2 Peripheric cortical subpleural Spreading: Singular. Multiple Unilateral Bilaterial Character of the clinical features Acute Chronic: In phase of the remission In phase of the exacerbation Connection with the bronchus: 1. It is not drained. 2. It is drained: There is enough There is not enough Complications: Empyema of the pleura Bleeding. Defeat of another lung Phlegmon of the thoracal wall. Bacterial shock Sepsis Etiology and Pathology Lung abscesses are usually due to infected material from the upper airway aspirated when a patient is unconscious or obtunded from alcohol, other drugs, CNS disease, general anesthesia, coma, or excessive sedation. The causative organisms are usually anaerobes. Lung abscesses are often associated with periodontal disease, in which anaerobes are prevalent. Bacteria cultured from lung abscesses include common and nasopharyngeal flora, particularly anaerobes, and less often, aerobic bacteria or fungi. Bronchogenic carcinoma is an occasional underlying cause in older smokers. Cavitary TB is not considered a lung abscess but must be remembered in the differential diagnosis. Pneumonia due to Klebsiella pneumoniae (Friedländer's bacillus), Staphylococcus aureus, Actinomyces israelii, -hemolytic streptococcus, Streptococcus milleri (and other aerobic or microaerophilic streptococci), Legionella sp, or Haemophilus influenzae is sometimes complicated by abscess formation. Lung abscess in the compromised host is usually due to Nocardia sp, Cryptococcus sp, Aspergillus sp, Phycomycetes sp, atypical mycobacteria (primarily Mycobacterium aviumintracellulare or M. kansasii), or gram-negative bacilli. Blastomycosis, histoplasmosis, and coccidioidomycosis may also cause acute or chronic lung abscesses and should be suspected in a person who has nonputrid abscesses and who lives in an endemic area. Less common causes of lung abscess include septic pulmonary emboli, secondary infection of pulmonary infarcts, and direct extension of amebic or bacterial abscesses from the liver through the diaphragm into the lower lobe of the lung. Single lung abscesses are most common. Multiple abscesses usually are unilateral; they may develop simultaneously or spread from a single focus. In abscesses due to aspiration, the superior segment of a lower lobe and the posterior segment of an upper lobe are affected most often. A solitary abscess secondary to bronchial obstruction or to an infected embolus starts as necrosis of a major portion of the affected bronchopulmonary segment. The base of the segment is usually next to the chest wall, and the pleural space in the area is often obliterated by inflammatory adhesions. Embolic spread of infection, most often due to S. aureus with tricuspid endocarditis in IV drug abusers, has become more common and is usually characterized by multiple lung lesions in noncontiguous sites. Suppurative venous thrombophlebitis due to aerobic or anaerobic bacteria may also cause embolic lung abscesses. An abscess usually ruptures into a bronchus, and its contents are expectorated, leaving a cavity filled with fluid and air. Occasionally, an abscess ruptures into the pleural cavity, resulting in an empyema, sometimes with bronchopleural fistula. Similarly, the rupture of a large abscess into a bronchus or vigorous attempts at drainage may cause widespread bronchial dissemination of pus with diffuse pneumonia and a condition resembling adult respiratory distress syndrome. Symptoms and Signs There are two periods of development this disease. The first period - before break of pus in the bronchi. Signs: Body temperature about 40 C Stethalgias on the side of defeat Backlog of the struck side in the act of respiration Morbidity at the palpation of the struck side The second period The second period begins after break of an abscess in bronchus (draining bronchus). Main signs Fast downstroke of temperature (37,5-38 C) A plenty of the sputum. The sputum is parted on three layers 1. Bottom Layer - pus 2. Average Layer - serous liquid 3. Top Layer - foam. Sometimes there is the impurity of blood. Onset may be acute or insidious. Early symptoms are often those of pneumonia, ie, malaise, anorexia, sputum-producing cough, sweats, and fever. Severe prostration and a temperature of 39.4° C (103° F) or higher may be present. Fever, anorexia, weakness, and debility are sometimes minimal if the infection is limited or indolent. Unless the abscess is completely walled off, the sputum is purulent and may be blood-streaked. An abscess may not be suspected until it perforates a bronchus, when a large amount of purulent sputum, putrid or not, may be expectorated over a few hours or several days. The sputum may contain gangrenous lung tissue. A putrid (penetrating and foul) odor is diagnostic of anaerobic bacterial causation. Putrid sputum occurs in 30 to 50% of all patients with lung abscess, but about 40% of patients with abscesses due to anaerobes do not have a putrid sputum, so its absence does not exclude this diagnosis. Chest pain, if present, usually indicates pleural involvement. Physical signs include a small area of dullness, indicating localized pneumonic consolidation, and usually suppressed (rather than bronchial) breath sounds. Fine or medium moist crackles may be present. If the cavity is large (unusual with current therapy), there may be tympany and amphoric breath sounds. Signs of pulmonary suppuration generally disappear with appropriate antibiotic therapy, but this disappearance does not necessarily denote cure. If the abscess becomes chronic, weight loss, anemia, and hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy may occur. Physical examination of the chest may be negative in the chronic phase, but rales and rhonchi are usually present. Diagnosis Methods of Diagnostics Chest Imaging conventional chest x-rays CT with or without contrast or high-resolution techniques angiography of the pulmonary or bronchial circulation using contrast materials or digital subtraction ultrasonography radionuclide scanning MRI. Diagnostic thoracentesis Thoracoscopy Bronchoscopy Ancillary procedures: Bronchoalveolar lavage Transbronchial lung biopsy Submucosal and transbronchial needle aspiration Percutaneous Transthoracic Needle Aspiration Thoracotomy Tracheal Aspiration Lung abscess is suggested by the symptoms and signs described above. Chest xrays early in the course may show a segmental or lobar consolidation, which sometimes becomes globular as pus distends it. After an abscess ruptures into a bronchus, a cavity with a fluid level appears on xray. If chest x-rays suggest an underlying tumor or foreign body or if the presentation is atypical, CT scanning may provide better anatomic definition. Sputum should be examined by smear and culture for bacteria, fungi, and mycobacteria. Expectorated sputum is not appropriate because the mouth normally contains anaerobic organisms that contaminate the specimen during passage through the upper airways. The attribution of disease to anaerobes usually requires a specimen obtained by transtracheal aspiration, transthoracic aspiration, or fiberoptic bronchoscopy with a protected brush and quantitative cultures, but these procedures are not performed often. Such invasive procedures should be reserved for cases that have an atypical presentation or that are unresponsive to antibiotics; however, once antibiotics are initiated, there is no reliable method for obtaining specimens useful for bacterial culture. Bronchoscopy is unnecessary if response to antibiotics is adequate and if a foreign body or tumor is not suspected. Lesions that simulate bacterial lung abscess include cavitating bronchogenic carcinoma, bronchiectasis, empyema secondary to a bronchopleural fistula, TB, coccidioidomycosis and other mycotic lung infections, infected pulmonary bulla or air cyst, pulmonary sequestration, silicotic nodule with central necrosis, subphrenic or hepatic (amebic or hydatid) abscess with perforation into a bronchus, and Wegener's granulomatosis. Repeated clinical evaluation and the procedures described above can usually differentiate these disorders from simple lung abscess. Prognosis and Treatment Prompt, complete healing of a lung abscess depends on adequate antibiotic treatment. Most patients recover without surgery. Antibiotics should be started as soon as sputum and blood have been collected for culture and sensitivity. The preferred drug is clindamycin, initially 600 mg IV tid, then 300 mg po qid. An alternative regimen is IV penicillin G 2 to 10 million U/day, followed by oral penicillin V 500 to 750 mg qid. Antibiotics are changed to oral when the patient is afebrile and subjectively improved. Some authorities prefer to combine penicillin with oral metronidazole 500 mg qid. If a gram-negative organism, S. aureus, or other aerobic pathogen is implicated, the antibiotic chosen depends on the results of sensitivity tests. Treatment should be continued until the pneumonitis has resolved and the cavity has disappeared, leaving only a small stable residual lesion, a thin-walled cyst, or clear lung fields. Resolution usually requires several weeks or months of treatment, much of which is given as oral antibiotics on an outpatient basis. Postural drainage may be a helpful adjunct, but it may also cause spillage of infection into other bronchi with extension of the infection or acute obstruction. If the patient is weak or paralyzed, tracheostomy and suctioning may be necessary. Rarely, bronchoscopic aspiration may help facilitate drainage. Surgical drainage is rarely necessary because lesions usually respond to antibiotics. Patients with large cavities who do not respond to drugs may be candidates for percutaneous drainage; patients with empyema require it. Pulmonary resection is the procedure of choice for an abscess resistant to drugs, particularly if bronchogenic carcinoma is suspected. Lobectomy is the most common procedure; segmental resection usually suffices for small lesions. Pneumonectomy may be necessary for multiple abscesses or pulmonary gangrene refractory to medical management. The mortality rate after pneumonectomy is 5 to 10%; after lesser resections, it is much lower. CHRONIC PULMONARY ABSCESS Pulmonary abscess which is not completed in two months (light weeks) is named chronical. If during acute pulmonary abscess the main morphologic sign is cavity with pus, walls of which consist from pulmonary tissue, during chronical abscess they are formed with connective tissue. Forming of connective capsula may be noted to the end of sixth-eighth week from the beginning of the disease. Pulmonary tissue around destruction cavity also concentrates. Pyogenic processin abscess cavity and complined inflammatory process in surrounding parenchyma mutually support each other. Gradually purrulent infiltration of surrounding pulmonary tissue is taring place. Opening into bronchial tree, singular a bscess promote generalization of process to brochi. Disturbans of bronchial peristalsis, obstruction of their lumen with pus lead to forming of focal atelectasis and secondary bronchiectasis. There are some important components of chronic pyogenic process in the lungs: 1) noneffective drainage 2) perypherical secondary bronchiectasis 3)changings in pulmonary tissue like sclerosis, deformation of bronchi This are the causes, promoting transformation of acute abcsesse into chronical: 1)unsatisfactory out flow of pus from cavity; 2)sequesters in abscess cavity; 3)hight pressure in the cavity; 4)forming of pleural commisures in defeated segments zone in lungs, which prevent early lung collapse and obliteration of cavity; 5)epithelization of cavity Treatment of acute abscess has been finishes with clinical convalescence. Patient is discharged from hospital with residual cavity. It leads to chronical purulent intoxication and othes complications. CLINICAL PICTURE The disease usually flows with aftern ation of aggravation and remission. The most constant symptom is tussis with purulent sputum. Quontity of sputum grows in aggravation period. During abundant expectoration the organism lose much protein, and it leads to inanition The maun complaun of patients with cronic abscess - asthenia (weakness); - bad appetite; - sleeplessness; - pain in thorax. - umpleasent smell from the mouth; - edematous face; - chement of ribs; - falling behing of the "sick" half of thorax during breathing; - fingers looking like "drum sticks" (may be seen in eighty five-ninty five per cent of cases) - deformation of nail plates like "watch glass". Symptomatology, found during physical examination of thorax is variable, it depends upon localisation of defeated zone, phaze of desease flow, availiability of changes in pleural cavity. In blood count - leucocytosis, deviation tothe left, anemia, hypoproteinemia. Spirography - lowering of vital capacity. There are some dystrophical changes in liver, heart. Differential diagnosis: 1)pulmonary tuberculosis: availiadility of tuberculosis foci of various remoteness in roentgenogram, sputum without any smell, but with typical bacteria. 2)Actinomycosis of lung - in sputum there are mycelium and drooze of radiant fungus. 3)Cancer of lung (cavital form): is characterized with beginning without high temperature, sputum without any smell with flood admixture, it includes "cancer" cells. Complications of 1) pulmonary hemorrhage 2) transformation into cancer 3) visceral amyloidosis TREATMENT Absolute depositions to operation are repeated pulmonary hemorrhage, quiqly growing intoxication. Only radical operation is effective (resection of lobe of the lung or pulmonectomy). Majority of patiens, who had lobecthomy, recover their capacity for work in three – four months after operation. After pulmonectomy in first six month patiens are transferred to invalidism.