Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia

advertisement

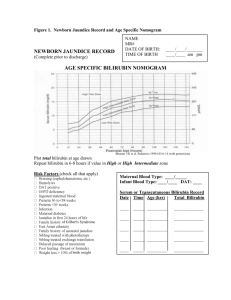

Teaching Module Hyperbilirubinemia Hyperbilirubinemia is a very common reason for admission to the pediatric ward. These patients are an example of a common challenge in pediatrics: finding the needle in a haystack. Kids are generally healthy, and generally even sick kids will become healthy regardless of our interventions or lack thereof. This can make it very difficult to pay careful attention to all kids, all the time. You can easily find yourself with your stethoscope on a chest and realize that you haven't really heard a thing. This must be balanced with the converse tendency, which is to catastrophize based on anecdote. You have heard one scary story about a “bili baby” - must you now obtain extensive (and expensive) labs on all infants all the time? I like to have a general framework of possible approaches to basic problems, and then refine that approach based on individual patient data. Residency is your time to make your frameworks, based on what you see done, what you read, and your own personal style. For bili babies in particular there is no one "right" answer, no single set of labs all babies must or must not have, no single approach to when to turn on or off the lights. Flashback to med school: BACKGROUND Physiology of bilirubin Bilirubin is breakdown product of hemoglobin. Some hemoglobin is released from ineffective erythropoiesis in the bone marrow, and by liver and tissue heme stores. The majority of hemoglobin results when senescent red blood cells are destroyed in the reticuloendothelial system. Altogether, the resulting hemoglobin is transformed by heme oxygenase to biliverdin. Biliverdin is converted by biliverdin reductase to bilirubin. Free bilirubin then enters the circulation. It is carried in a bilirubin-albumin complex to the liver. Within hepatocytes, bilirubin is conjugated with glucuronic acid (catalyzed by uridine diphosphate glucuronosyl transferase, UGT). Conjugated bilirubin is then excreted into the gut. In adults, conjugated bili is quickly broken down by bacteria, and then excreted. In babies, the enzyme beta glucuronidase "de"conjugates the bilirubin, and the resulting unconjugated bilirubin is then reabsorbed into the circulation in a process called enterohepatic recirculation. Enterohepatic recirculation therefore increases the concentration of unconjugated bilirubin. Thus, improving the movement of stool through and out of the intestines can decrease the enterohepatic recirculation and thus decrease the bilirubin load. Physiology of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia Several factors contribute to the normal rise in bilirubin in the first week of life. 1. Increased bilirubin load: there is increased red cell turnover because of increase red blood cell volume and decreased life span. There is also increased enterohepatic recirculation. And there is increased bilirubin from ineffective erythropoiesis. 2. Decreased excretion: this is mainly due to the decreased activity of UGT The typical time course of hyperbilirubinemia is that it usually peaks day of life 3-5, later in Hispanic kids. Why does it happen at all?? There has recently been some interest in the role of bilirubin as an antioxidant. It would seem that there should (over millennia) have been evolutionary pressure to eliminate postnatal bilirubin problems. For hyperbilirubinemia to continue to be part of normal newborn period, it is reasonable to search for whether there is any survival advantage to its presence. Bilirubin is an antioxidant. Perhaps bilirubin rise has persisted as a way to counter the sudden increase in oxidative stressors that happens with the change from prenatal to postnatal life. There is evidence in premies that reducing the bilirubin TOO MUCH may be harmful. Monica Stemmle, M.D. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY of hyperbilirubinemia - when bilirubin gets abnormally high Risk factors for bilirubin increasing more than normal are: Factors that increase bilirubin load: Hemolysis: immune mediated (most commonly from ABO incompatibility, can also be from rH), or heritable (red cell membrane defect, red cell enzyme defects such as G-6-PD, hemoglobinopathies. Sepsis/DIC Hematomas (most often cephalohematomas, can also be abdominal or intracranial) Polycythemia Macrosomia Increased enterohepatic circulation, as in breast feeding failure jaundice Factors that decrease bilirubin clearance: G-6-PD deficiency Pathophysiology of KERNICTERUS Physiology of kernicterus is NOT well understood. It’s most likely that exposure to bilirubin at sensitive window of neuronal development/differentiation may lead to apoptosis. Prolonged high bilirubin is required. Although this is deeply unsatisfying, here is no one number that is a dividing line between always kernicterus and never kernicterus. Probably what happens is, there is are at least 2 hits - high bili, and a pre-disposing alteration in the blood brain barrier (sepsis, etc) Trends in diagnosis for newborn jaundice were u-shaped, with rates falling in the years before the initial American Academy of Pediatrics guideline (1988–1993) and increasing in the years after publication of the guideline (1997–2005). In contrast, the number of newborn hospitalizations with a diagnosis of kernicterus generally declined throughout the study period. Most of the decline in hospitalizations for term infants with a diagnosis of kernicterus occurred before and immediately after publication of the 1994 guideline, going from 5.1 per 100000 in 1988 to 1.5 per 100000 in the years from 1994 to 1996 and has since remained constant. So, the continuing increase in hospitalizations for jaundice has not caused a continuing DECREASE in kernicterus. (Burke et al, see references), What data are out there for what level causes kernicterus? 1. Outcomes among Newborns with Total Serum Bilirubin Levels of 25 mg per Deciliter or More Thomas B. Newman N Engl J Med 354;18 may 4, 2006 Studied Kaiser data set and looked at all infants with bili >24, and found no cases of kernicterus. Compared hyperbili kids to controls and found essentially no neurologic differences, though DAT positive kids had very slightly worse cognitive function 2. Outcomes in a Population of Healthy Term and Near-Term Infants With Serum Bilirubin Levels of >19 mg/dL Who Were Born in Nova Scotia, Canada, Between 1994 and 2000. Pediatrics. Jangaard et al. 122 (1): 119. (2008). Looked at all babies born in Nova Scotia 1994-2000. No difference in neuro problems or deafness between "severe hyperbili" (>19) or "no hyperbili" (<13). Very few cases >30, and did not discuss really whether kids got photo or not, and control group did not all have bilis measured. So, might have been an effect that was masked 3. Synopsis report from the Pilot USA Kernicterus Registry VK Bhutani and L Johnson Journal of Perinatology (2009) 29, S4–S7. In this apparently voluntary registry, no cases of kernicterus occured at bili <20, very unusual 20-25, and 25-35 seemed to be potentially reversible if treatment undertaken promptly. Monica Stemmle, M.D. So – there’s imperfect evidence. Who should we screen? Controveries and (lack of) consensus Read the October 2009 Pediatrics for an interesting clash of opinions. The choices for screening are basically 1) based on risk factors and clinical assesment versus 2) universal screening. AAP guidelines of 2004: A TcB and/or TSB measurement should be performed if the jaundice appears excessive for the infant’s age. If there is any doubt about the degree of jaundice, the TSB or TcB should be measured. AAP Commentary of 2009: We recommend that a predischarge measurement of TSB or TcB be performed and the risk zone for hyperbilirubinemia determined on the basis of the infant’s age in hours and the TSB or TcB measurement. In other words, the AAP now "recommends" universal objective screening (either TcB or TSB). Why did the AAP change the recommendation? Three studies are cited: One shows that objective screening combined with clinical assessment is a little better than clinical alone. The other shows adding clinical assessment to objective screening is helpful. The third study is the only one that truly supports this change, showing that objective measurement of bili PLUS clinical risk factors is better than either objective or clinical factors alone. (Routine transcutaneous bilirubin measurements combined with clinical risk factors improve the prediction of subsequent hyperbilirubinemia, MJ Maisels, Journal of Perinatology 2009). But the study is not ideal (the number is small and the definition of “hyperbili” is greater than 17, which is a little low). The real rationale seems to be described in the accompanying editorial by Dr Newman. Basically, there is a chance of error if using clinical assessment - nurseries are busy, and we all know errors and omissions happen, so this is the SAFEST thing. Some of the most persuasive and loudest voices out there feel that kernicterus should be a “never” event, and therefore almost any amount of screening is worth it. However, the USPSTF disagrees. Their recommendation (in that same issue of Pediatrics) is that the evidence is insufficient to recommend universal screening. What are the risks if we screen too much? Cost – includes cost of screening AND cost of treating some children unnecessarily False positives – vulnerable child syndrome. There’s conflicting literature on this, but it’s a possibility. Risk of interrupting breastfeeding Increased treatment – blue light may increase nevus formation, though literature is conflicting there too. In brief: We’re all using objective (transcutaneous or serum bili) and clinical criteria to screen for hyperbili. But we are doing that based on less evidence than might be assumed. And though we assume there are no risks to screening, this is actually not the case. Who should we treat? Controversies and (lack of) consensus The idea is, you would like to prevent kernicterus. The trouble is, you do not know at exactly what level kernicterus occurs, and it does seem to be different levels depending on risk factors. In deciding whether to treat or not, the AAP has a set of risk factors for achieving high bilirubin levels. These are: Predischarge TSB or TcB measurement in the high-risk or high-intermediate–risk zone Lower gestational age Monica Stemmle, M.D. Exclusive breastfeeding, particularly if nursing is not going well and weight loss is excessive Jaundice observed in the first 24 h Isoimmune or other hemolytic disease (eg, G6PD deficiency) Previous sibling with jaundice Cephalohematoma or significant bruising East Asian race These factors influence a baby’s risk of developing a high bilirubin level. They are NOT the baby’s risk for kernicterus. Then the AAP has risk factors for developing “neurotoxicity”. Honestly, the rates of kernicterus are so low, it is impossible to come up with good risk factors for kernicterus, so instead they use “neurotoxicity.” These are: isoimmune hemolytic disease G6PD deficiency asphyxia sepsis acidosis albumin <3.0 mg/dL. There are 3 main charts in the AAP commentary/guidelines papers. These charts are: Risk zones Phototherapy Exchange transfusion Risk zones: This is NOT the baby’s risk of developing kernicterus. Or neurotoxicity. It is the baby’s risk of developing a bili that is =>95%ile for age. For low risk kids, this would not even meet the AAP’s guidelines for initiation of phototherapy. In Bhutani’s initial paper publishing these guidelines, 60% of kids who had a predischarge TSB in the “high risk” zone, had subsequent bilis below that zone. So, this graph is only useful in giving a broad guideline of when to check the next bili, IF EVER. Monica Stemmle, M.D. When to perform phototherapy/exchange transfusion? Most pediatricians simply use the AAP guidelines. Here is the chart for phototherapy. But how did those guidelines get made? Expert consensus. It is based on attempting to prevent ever reaching the levels that seem associated with kernicterus, but it is a guess. Are these guidelines valid? The short answer is, we have no idea. But an interesting take on this question is this article by Tom Newman: Numbers Needed to Treat With Phototherapy According to American Academy (Thomas B. Newman, Michael W. Kuzniewicz, Petra Liljestrand, Soora Wi, Charles McCulloch and Gabriel J. Escobar. Pediatrics 2009;123;1352-1359). In this article, they used the Kaiser database, looking at infants with bilirubin +/- 3 from AAP rec for photo. They used these infants to estimate the number needed to treat according to guidelines to prevent one from rising to level of recommended exchange (also per AAP guidelines). For avg babies (=>38wks, AGA, negative DAT, >48 hours at qualifying TSB) NNT was >200, up to >1000 for 40 weekers at 48+ hours. In other words, guidelines appear internally inconsistent and quite conservative. And remember, this is to prevent a single baby from reaching the AAP guideline for exchange, NOT to prevent a case of kernicterus. So the AAP’s guidelines truly ARE just that; guidelines. There is imperfect evidence in this field, as in so much else in medicine. I think when you look closely at how almost all guidelines are made, you find that there is less evidence and more “consensus” than feels truly scientific. And yet, it’s the best we have. So, I do think it is appropriate to use the AAP guidelines AS guidelines – and if you feel there are other circumstances at play, use those. If you find there is a mom with lots of experience and excellent follow-up and a clear (and fixable) reason for hyperbili, you can elect to NOT do photo, despite the guidelines, and simply follow up a day later. And when you see that mom in court, tell her, Monica sent you. Ha! Monica Stemmle, M.D. Seriously, I think the key features I’d like you to remember about hyperbilirubinemia are: 1. The reason for the hyperbili is JUST as important as the level of bilirubin 2. Vitals are actually vital 3. Guidelines are actually guidelines – clinical judgment in conjunction with guidelines is often safer, and almost always more cost effective, than slavish devotion to rules OK – now you know everything. Practice being the doctor with this actual case: You are the Valley cross cover Junior and have 3 admissions who have all just arrived on the floor on a busy winter night. They are: 1. Bronchiolitis 2. Hyperbilirubinemia 3. Possible Kawasaki’s Your senior is busy in the PICU/Well Baby/Call room watching American Idol. Your intern is the transitional and there’s a med student begging to do an H&P. What do you do? Don’t you always have to “divide and conquer”? I think a big part of junior year is deciding how to triage. In looking at that list, I would probably figure that the bronchiolitic should be looked at by the most experienced physical examiner first. And the hyperbili baby could be started by the transitional. And the Kawasaki’s, while an interesting case, is unlikely to progress much in the next hour. So I’d probably start the med student on that H&P figuring they will be the most complete of any of you. But this isn’t a question with a “right” answer. You quickly see the bronchiolitic, and meet up with the transitional out at the nurses desk. What are some factors to immediately get from the intern about the bili baby? a. Baby’s gestational age and chronologic age b. Baby’s bili level c. Baby’s vital signs d. Baby’s blood type and mom’s blood type Answer: A, B, C, D. All important. Intern says: baby is a 6 day old ex 36 0/7 week with a bili of 15.8. Vital signs not done yet. Mom is A positive, antibody screen negative. And the baby’s name is Angel. What places this baby at higher risk for severe hyperbilirubinemia? a. Late preterm infant b. Mom’s blood type c. Male d. 6 days old Answer: A and C More H, more P: The intern mentions that the baby is approximately 3% down from birth weight, being fed a combination of breast and bottle. He looks “fine” and does not have hepatomegaly. Why do you think the baby has hyperbili? a. Breastfeeding jaundice b. Breastmilk jaundice c. Exaggerated physiologic jaundice d. Other Monica Stemmle, M.D. Answer: C or D. You have no convincing explanation for the hyperbili. What labs would you like to get? a. CBC b. Retic c. Direct bili d. Type and Coombs Answer: A, B, C, and maybe D. I think you have no good explanation for the hyperbili, so it is helpful to see if more information can come from the labs. You order the labs, and as you're waiting for the results, the nurse approaches to mention that the baby has low tone. What do you do now? a. Examine the baby b. Eat dinner c. Send some more labs Answer: Examine the baby. Hey, there’s no substitute for your own judgment. Transitional interns are still learning what a “normal” baby looks like. Baby DOES appear to be hypotonic. And does not suck much. The temperature on admission was low, though it improved after placing into the isolette for phototherapy. And by the way, the perfusion is somewhat poor. You decide this warrants a full rule out sepsis, so you decide to tap. What do you need to gather for your tap? Answer: The usual stuff (LP kit, extra needle, gloves, betadine). In the procedure room on pedi at Valley, you should familiarize yourself with a couple things. First, there is not a sat monitor in there. So if you want one (and if a kid has poor perfusion, you should want one), you’ll have to ask a nurse to bring it in. Second, there is an ambu bag near the head of the procedure bed. And third, there are warming pads on top of the procedure cart, in the back left corner of the room. You can a nurse how to activate them. Babies can lose heat quickly, so it’s very helpful to have a warmer under them. During the tap, baby has a respiratory arrest – you were SO SMART to put that sat monitor on! You and your team begin bag mask ventilation and transfer to the NICU. Within minutes the lab calls to tell you that the CBC shows a WBC of 3.7, and on the differential they note "many bacteria". Phototherapy suddenly seems like the least of this baby's concerns. There were several warning signs that this case was not a simple case of isolated neonatal jaundice. They were: 1. Abnormal vital sign (low temp) 2. No clear cause of hyperbili 3. Poor perfusion Answer: all of the above. And DO NOT let this anecdote make you check for sepsis in all babies with hyperbili. In fact, that is exactly NOT the point. The point it, hyperbili is NOT the most serious disease of infancy – SEPSIS is. Monica Stemmle, M.D. To reiterate: 1. The reason for the hyperbili is JUST as important as the level of bilirubin 2. Vitals are actually vital 3. Guidelines are actually guidelines – clinical judgement in conjunction with guidelines is often safer, and almost always more cost effective, than slavish devotion to rules 4. If you must use the guidelines, remember that the Bhutani nomogram is only useful for deciding when to obtain the next bili, NOT necessarily for starting photo. The guidelines for starting photo are internally inconsistent and should be tempered with clinical judgment. REFERENCES Hyperbilirubinemia in the Newborn Infant >35 Weeks’ Gestation: An Update With Clarifications M. Jeffrey Maisels Vinod K. Bhutani, Debra Bogen, Thomas B. Newman, MD, Ann R. Stark, and Jon F. Watchko PEDIATRICS Volume 124, Number 4, October 2009 This is the big article that guides how most pediatricians practice Screening of Infants for Hyperbilirubinemia to Prevent Chronic Bilirubin Encephalopathy: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement US Preventive Services Task Force Pediatrics 2009; 124;1172-1177 This is an alternative view about whether what we do is worth it. Neonatal Jaundice M. Jeffrey Maisels Pediatr. Rev. 2006;27;443-454 Good review of basics, great to hand out to med students Trends in Hospitalizations for Neonatal Jaundice and Kernicterus in the United States, 1988_2005 Bryan L. Burke, James M. Robbins, T. Mac Bird, Charlotte A. Hobbs, Clare Nesmith and John Mick Tilford Pediatrics 2009;123;524-532 Monica Stemmle, M.D.