Basal Cell Carcinoma

advertisement

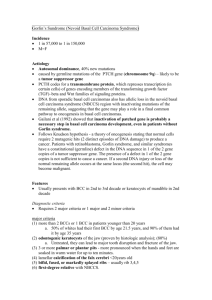

Basal Cell Carcinoma Author: Michael L Ramsey, MD, Director, Mohs Surgery Fellowship, Co-Director, Procedural Dermatology Fellowship, Department of Dermatology, Geisinger Medical Center Coauthor(s): Lindsay Dane Sewell, MD, Staff Physician, Department of Dermatology, Geisinger Medical Center Contributor Information and Disclosures Updated: Sep 11, 2009 Introduction Background Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common malignancy in humans. It typically occurs in areas of chronic sun exposure. BCC is usually slow growing and rarely metastasizes, but it can cause clinically significant local destruction and disfigurement if neglected or inadequately treated. Prognosis is excellent with proper therapy. Pathophysiology Many believe that basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) arise from pluripotential cells in the basal layer of the epidermis or follicular structures. These cells form continuously during life and can form hair, sebaceous glands, and apocrine glands. Tumors usually arise from the epidermis and occasionally arise from the outer root sheath of a hair follicle, specifically from hair follicle stem cells residing just below the sebaceous gland duct in an area called the bulge. The patched/hedgehog intracellular signaling pathway plays a role in both sporadic BCCs and in nevoid BCC syndrome (Gorlin syndrome). This pathway influences differentiation of a variety of tissues during fetal development. After embryogenesis, it continues to function in regulation of cell growth and differentiation. Loss of inhibition of this pathway is associated with human malignancy, including BCC. The hedgehog gene encodes an extracellular protein that binds to a cell membrane receptor complex to start a cascade of cellular events leading to cell proliferation. Of the 3 known human homologs, Sonic hedgehog (SHH) protein is the most relevant to BCC. Patched (PTCH) is a protein that is the ligand-binding component of the hedgehog receptor complex in the cell membrane. The other protein member of the receptor complex, smoothened (SMO), is responsible for transducing hedgehog signaling to downstream genes.1,2 When SHH is present, it binds to PTCH, which then releases and activates SMO. SMO signaling is transduced to the nucleus via Gli. When SHH is absent, PTCH binds to and inhibits SMO. Mutations in the PTCH gene prevent it from binding to SMO, simulating the presence of SHH . The unbound SMO and downstream Gli are constitutively activated, thereby allowing hedgehog signaling to proceed unimpeded. The same pathway may also be activated via mutations in the SMO gene, which also allows unregulated signaling of tumor growth. How these defects cause tumorigenesis is not fully understood, but most BCCs have abnormalities in either PTCH or SMO genes. Some even consider defects in the hedgehog pathway to be requirements for BCC development. UV-induced mutations in the TP53 tumor suppressor gene, which resides on band 17p13.1, have been found in some cases of BCC.3 Activated BCL2 (an antiapoptosis proto-oncogene) also is commonly found in BCCs and may be detected immunohistochemically. Frequency United States The annual incidence of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is approximately 900,000 cases (550,000 in men, 350,000 in women). The age-adjusted incidence per 100,000 white individuals is 475 cases in men and 250 cases in women. The estimated lifetime risk of BCC in the white population is 3339% in men and 23-28% in women. Mortality/Morbidity Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) can cause clinically significant morbidity if allowed to progress. Because this cancer most commonly affects the head and neck, cosmetic disfigurement is not uncommon. Loss of vision or the eye may occur with orbital involvement. Perineural spread can result in loss of nerve function and in deep and extensive invasion of the tumor. These neoplasms are often friable and prone to ulceration; thus, they provide a nidus for infection. Death from BCC is extremely rare. Race Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is generally a disorder of white individuals, especially those with fair skin. It is rare in dark-skinned individuals. Sex The male-to-female ratio for basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is approximately 3:2. Age Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) most commonly occurs in adulthood, especially in elderly persons. Clinical History Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) patients often present with a nonhealing sore of varying duration. The lesions are typically seen on the face, ears, scalp, neck, or upper trunk. Mild trauma, such as face washing or drying with a towel, initially may cause bleeding. A history of chronic recreational or occupational sun exposure is commonly elicited. Intense sun exposure often occurred in childhood or young adulthood. Physical Several clinical and histologic subtypes of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) may exhibit different patterns of behavior. Recognizing the various types is important because aggressive therapy is often necessary for variants such as micronodular, infiltrating, or morpheaform BCC. When one examines possible skin cancers, the best plan is to use good lighting and magnification. The affected skin should be stretched, squeezed, and palpated to best estimate the size and depth of the tumor. Oblique illumination of the tumor can highlight surface changes, such as a rolled border. Nodular BCC: This is the most common variety of BCC. Nodular BCCs most commonly occur on the head, neck, and upper back. They may have some of the following features: o Waxy papules with central depression (see Media File 2) o Pearly appearance o Erosion or ulceration o Bleeding o Crusting o Rolled (raised) border (see Media Files 4-5) o Translucency o Telangiectases over the surface o History of bleeding with minor trauma Nodular basal cell carcinoma appearing as a waxy, translucent papule with central depression and a few small erosions. Scale, erythema, and a threadlike raised border are present in this superficial basal cell carcinoma on the trunk. Large, superficial basal cell carcinoma. Pigmented BCC: In addition to features seen in lesions of nodular BCC, lesions of pigmented BCC contain increased brown or black pigment and are most common in individuals with dark skin (see Media File 7). Pigmented basal cell carcinoma has features of nodular basal cell carcinoma with the addition of dark pigmentation from melanin deposition. The pigmentation often has the appearance of dark droplets in the lesion, as shown here. Cystic BCC: Lesions of cystic BCC are translucent blue-gray cystic nodules that may mimic benign cystic lesions. Superficial BCC: This variety appears as scaly patches or papules that are pink to redbrown, often with central clearing. A threadlike border is common. Erosion is less common in superficial BCC than in nodular BCC (see Media File 1). Superficial BCC is common on the trunk and has little tendency to become invasive. The papules may mimic psoriasis or eczema, but they are slowly progressive and not prone to fluctuate in appearance. Numerous superficial BCCs may indicate arsenic exposure. This translucent pink papule has telangiectases and a crusted erosion, characteristic of nodular basal cell carcinoma. Micronodular BCC: This aggressive BCC subtype has the typical BCC distribution. It is not prone to ulceration, it may appear yellow-white when stretched, and it is firm to the touch. It may have a seemingly well-defined border. Morpheaform and infiltrating BCC: These are aggressive BCC subtypes with sclerotic (scarlike) plaques or papules. The border is usually ill defined and often extends well beyond clinical margins. Ulceration, bleeding, and crusting are uncommon. It may be mistaken for scar tissue (see Media 8 and Media File 10). This infiltrating basal cell cancer has ill-defined borders and telangiectases. Large, scarlike morpheaform basal cell cancer. Younger patients (<40 y) may have a lower prevalence of BCC on the head and neck and a higher prevalence on the trunk, with greater tendency to superficial BCC, than in older patients.4 Childhood BCC is exceedingly rare in the absence of other underlying conditions. Only 107 cases of de novo childhood BCC have been reported in the literature, but the majority (90%) occurred on the head and neck, and aggressive subtypes were observed in 20% of the total cases.5 Causes UV radiation: This is the most important and common cause of basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Short-wavelength UV radiation (290-320 nm, sunburn rays) is believed to play a greater role in BCC formation than long-wavelength UVA radiation (320-400 nm, tanning rays). In addition, chronic sun exposure appears to be important in the development of BCC. A latency period of 20-50 years is typical between the time of UV damage and the clinical onset of BCC. Other radiation: X-ray and grenz-ray exposure are associated with BCC formation. Arsenic exposure: Chronic exposure to arsenic is associated with BCC development. Exposure may be medicinal, occupational, or dietary. A contaminated water supply is most commonly implicated. Immunosuppression: Immunosuppression is associated with a modest increase in the risk of BCC. Xeroderma pigmentosum: This autosomal recessive disease predisposes people to rapid aging of exposed skin, starting with pigmentary changes and progressing to BCC, squamous cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma. The effects are due to an inability to repair UV-induced DNA damage. Other features include corneal opacities, eventual blindness, and neurologic deficits. Nevoid BCC syndrome (basal cell nevus syndrome, Gorlin syndrome): Multiple BCCs occur in this autosomal dominant condition, often starting at an early age. Odontogenic keratocysts, palmoplantar pitting, intracranial calcification, and rib anomalies may be seen. Various tumors, such as medulloblastomas, meningioma, fetal rhabdomyoma, and ameloblastoma, can also occur. Mutations in the hedgehog signaling pathway, particularly the PTCH gene, are causative.6 Bazex syndrome (Bazex-Dupre-Christol syndrome): This is an x-linked dominant condition with features of follicular atrophoderma (ice-pick marks, especially on dorsum of the hands), multiple BCCs, local anhidrosis (decreased or absent sweating), and congenital hypotrichosis.7 Rombo syndrome8 : This is an autosomal dominant condition distinguished by BCC and atrophoderma vermiculatum, trichoepitheliomas, hypotrichosis milia, and peripheral vasodilation with cyanosis. History of nonmelanoma skin cancer (BCC or squamous cell carcinoma): Persons with one nonmelanoma skin cancer are at increased risk of developing others in the future. The rate of new nonmelanoma skin cancer is 35% at 3 years and 50% at 5 years after an initial diagnosis of skin cancer.9 Basal Cell Carcinoma: Differential Diagnoses & Workup Differential Diagnoses Actinic Keratosis Sebaceous Hyperplasia Bowen Disease Seborrheic Keratosis Fibrous Papule of the Face Squamous Cell Carcinoma Keratoacanthoma Trichoepithelioma Nevi, Melanocytic Workup The following clinical guideline summaries may be helpful: US Preventive Services Task Force - Screening for skin cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement10 Cancer Care Ontario - Screening for skin cancer: a clinical practice guideline11 Procedures Skin biopsy: Biopsy is required to confirm the diagnosis and to identify the histologic subtype of the basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Shave or punch biopsy is usually performed. Additional workup is rarely necessary, unless a genetic disorder is suspected. o Shave biopsy suffices for the diagnosis of most BCCs. Avoid taking an exceedingly superficial biopsy specimen because missing the tumor is possible. For example, an ulcerated BCC may reepithelialize with normal epidermis while a tumor is present at a deeper level. Part or all of the BCC may be sampled, but avoid going beyond the clinical margins if the biopsy is only for diagnostic purposes. o Punch biopsy is an easy method to obtain a thick specimen. The most suspicious area of a lesion may be sampled, or multiple biopsy samples may be taken if the tumor has different appearances in different areas. Avoid punch biopsy if curettage is planned for final treatment. Histologic Findings Tumor cells of nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC), sometimes called basalioma cells, typically have large, hyperchromatic, oval nuclei and little cytoplasm. Cells appear uniform, and, if present, mitotic figures are usually few. Nodular tumor aggregates may be of varying sizes, but tumor cells tend to align more densely in a palisade pattern at the periphery of these nests (see Media File 3). Early lesions usually have some connection to the overlying epidermis, but such contiguity may be difficult to appreciate in more advanced lesions. Increased mucin is often present in the surrounding dermal stroma. Nodular basal cell carcinoma. Nodular aggregates of basalioma cells are present in the dermis and exhibit peripheral palisading and retraction artifact. Melanin is also present within the tumor and in the surrounding stroma, as seen in pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Cleft formation, known as retraction artifact, commonly occurs between BCC nests and stroma because of shrinkage of mucin during tissue fixation and staining. Some lobules may have areas of pseudoglandular change, and this is the predominant change in adenoid BCC. In other instances, large tumor lobules may degenerate centrally, forming pseudocystic spaces filled with mucinous debris. These changes are seen in the nodulocystic variant of BCC (see Media File 6). Histology of superficial basal cell carcinoma. Nests of basaloid cells are seen budding from the undersurface of the epidermis. Numerous variants occur, including pigmented BCC, in which benign melanocytes in and around the tumor produce large amounts of melanin. These melanocytes contain many melanin granules in their cytoplasm and dendrites. Superficial BCC appears as buds of basaloid cells attached to the undersurface of the epidermis. Nests of various sizes are often seen in the upper dermis. The tumor cell aggregates typically show peripheral palisading. The more aggressive morpheaform and infiltrating BCCs have growth patterns resulting in strands of cells rather than round nests. Morpheaform BCC arises as thin strands of tumor cells (often only 1 cell in thickness) that are embedded in a dense fibrous stroma. The strands of infiltrating BCC tend to be somewhat thicker than those seen in morpheaform BCC, and they have a spiky, irregular appearance. Infiltrating BCC usually does not exhibit the scarlike stroma seen in morpheaform BCC. Peripheral palisading and retraction are less pronounced in morpheaform and infiltrating BCC than in less aggressive forms of the tumor, and subclinical involvement is often extensive. Another aggressive variant, micronodular BCC, appears as small, nodular aggregates of basaloid cells. Retraction artifact tends to be less pronounced than in the nodular form of BCC, and subclinical involvement is often significant. Basosquamous carcinoma, which exhibits features of both BCC and squamous cell carcinoma, is also considered an aggressive skin cancer. Basal Cell Carcinoma: Treatment & Medication Treatment Medical Care Local therapy with chemotherapeutic and immune-modulating agents is useful in some cases of basal cell carcinoma (BCC). In particular, small and superficial BCC may respond to these compounds. In addition, they may be used for prophylaxis or maintenance in patients who are prone to having many BCCs, such as those with basal cell nevus syndrome. See Medication. Also see the clinical guideline summary from the British Association of Dermatologists, Guidelines for the management of basal cell carcinoma.12 Surgical Care The goal of surgical treatment of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is to destroy or remove the tumor so that no malignant tissue is allowed to proliferate further. Factors to consider when choosing therapy include the histologic subtype of BCC, the location and size of tumors, the age of the patient, the patient's ability to tolerate surgery, and the expense. Recurrent tumors are generally more aggressive than primary lesions, and subclinical extension also tends to be increased. Tumors that are aggressive and those occurring near vital or cosmetically sensitive structures are best treated with methods that allow for an examination of the tissue margins. The most common surgical methods are curettage, excision with margin examination, Mohs micrographic surgery, and radiotherapy. Additionally, cryotherapy is sometimes used to treat these tumors (see Media File 9). Postoperative wound after Mohs micrographic surgery demonstrates extensive subclinical involvement typical of many infiltrating and morpheaform basal cell carcinomas. Curettage (usually with electrodesiccation) for basal cell carcinoma13 o A looped blade (curette) is used to vigorously scrape tumor away from adjacent normal skin. One may start with a larger curette to debulk the tumor and then follow with a smaller curette to better remove smaller fragments of tumor from surrounding stroma. This technique works best in nodular or superficial BCC because these tumors tend to be friable and do not tend to be embedded in fibrous stroma. The instrument is applied firmly and used in multiple directions over the tumor and immediately adjacent skin. Curetting is most often followed by electrodesiccation, and the entire process may be repeated 1-2 more times. If electrodesiccation is not performed, vigorous and firm scraping in several directions is especially important. Many recurrences after curettage are believed to be due to insufficient aggressiveness on the part of the surgeon. The overall cure rate exceeds 90% for low-risk BCCs. The method is quick, simple, and less expensive than most other methods. o Curettage is a blind technique in which the specimen cannot be examined for margin control. This lack of microscopic margin control limits the usefulness of curettage in high-risk areas, such as the face and ears. Furthermore, the aggressive subtypes of BCC, such as morpheaform, infiltrating, micronodular, and recurrent tumors, are usually not friable and therefore unlikely to be removed by using the curette. The success of this treatment, even in nonaggressive tumors in low-risk sites, highly depends on the operator's experience and technique. Finally, healing by secondary intention (granulation) often leads to atrophic, white scars that may not be satisfactory in aesthetically important areas. Surgical excision for basal cell carcinoma14 o One may surgically excise the clinically apparent tumor and a margin of clinically normal–appearing skin. This method can usually be performed in an ambulatory setting and provides the pathologist with a specimen to examine the tissue margins. Healing time is generally shorter with sutured closure than with granulation, and cosmesis compares favorably with that of curettage. o Surgical excision is more time-consuming and costly than curettage. In addition, this method requires sacrifice of normal tissue to obtain acceptable cure rates. Margins of at least 4 mm are needed, even with the least aggressive BCCs, to achieve 95% cure rates. If standard bread-loaf tissue sectioning is used, areas of margin involvement may be missed under microscopy because only a small sampling of the specimen is evaluated. Mohs micrographic surgery for basal cell carcinoma15,16 o Mohs surgery involves removal of the clinically apparent tumor and a thin rim of normal-appearing skin around the defect. This saucer-shaped tissue specimen represents tissue adjacent to the tumor or the margin surrounding the tumor. This margin specimen is sectioned and marked so that the entirety of the undersurface and outer edges of the tumor are examined microscopically to minimize sampling error. Use of the frozen-section technique allows for an examination of tissue while the patient is in the office. Tissue is mapped microscopically so if any foci of tumor persist, further excision can be directed to only those areas to spare the normal tissue. o With the Mohs technique, almost 100% of the tissue margins are examined, compared with standard vertical (bread-loaf) sectioning, in which less than 1% of the outer margins are examined. Because relatively thin layers are taken only in areas of proven tumor, this technique is tissue sparing. Excision and repair can usually be performed on the same day. Of most importance, Mohs micrographic surgical excision has the best long-term cure rates of any treatment modality for BCC. Cure rates for primary BCC are 98-99% with Mohs excision and 94-96% for recurrent BCC. o Massive, invasive BCC tumors may sometimes be treated with Mohs surgery to clear peripheral margins with deeper aspects treated surgically by other disciplines.17 o Chief disadvantages of Mohs surgery are its increased expense and time requirement compared with curettage. Mohs excision compares favorably with standard surgical excision when one factors in the savings of treating fewer recurrences with this technique. Radiation therapy for basal cell carcinoma18 o Radiation therapy is effective as primary treatment for a variety of BCCs. For most BCCs, cure rates approach 90%. It is especially useful for patients who cannot easily tolerate surgery, such as elderly or debilitated individuals. Irradiation can also be a useful adjunct when patients have aggressive tumors that were treated surgically or when surgery has failed to clear the margins of the tumor. Radiation is also an excellent option in patients who refuse surgery because of the size of a lesion or its proximity to vital structures. o Initial cosmetic results tend to be good, and this therapy can be less disfiguring than surgical excision. However, long-term results after several years can be deforming. Another disadvantage of this technique is that surgical margins cannot be examined. Tumors recurring in previously radiated sites tend to be aggressive and difficult to treat and reconstruct. Radiation therapy remains an important, feasible option in selected patients with BCC. Cryotherapy for basal cell carcinoma o Cryotherapy is also an effective treatment for most nonaggressive BCCs, with cure rates near 90%. However, successful treatment is highly dependent on the experience of the operator. Optimal cure rates are obtained when the depth, duration, and temperature of treatment are measured with special instrumentation, such as cryoprobes. o Patients must be willing to endure the immediate posttreatment swelling, resultant necrosis of treated areas, and unpredictable scarring that can occur with this approach. o This method is not commonly used for the treatment of BCC, except by a few experienced cryosurgeons. Medication Imiquimod 5% cream19 has been used successfully to treat superficial basal cell carcinomas (BCCs).19,20,21,22 Although its exact mode of action in treating BCC is not known, a few suggested mechanisms follow. Lymphocytes, dendritic cells, and macrophages may be recruited into the area of imiquimod application. These cells may be activated via toll-like receptors 7 and 8 (both of which recognize imiquimod as a ligand) to release cytokines, particularly tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interferon-alpha, and interleukin 6. Antitumor effects, such as apoptosis, may then proceed, thereby inducing tumor regression.23 Induction of tumor suppressor function via the Notch signaling pathway in superficial BCCs has also been suggested as a mechanism of imiquimod.21,24 The current recommended dosing frequency for the treatment of superficial BCC is 5 times per week for 6 weeks, but the frequency and duration should be tailored to the individual patient's response and ability to tolerate the medication. Many application schedules have been used, ranging from 3 times per week to twice daily 7 d/wk. The duration of treatment varies from 6-16 weeks. Superficial BCC cure rates of 70-100% should be expected after a 6-week course of 5times-per-week application, as shown in studies. Topical imiquimod has also been used to treat small, nodular BCCs in low-risk locations, but cure rates have been lower than those with superficial BCCs. Although successful use of imiquimod in immunosuppressed populations (eg, transplantation patients) without systemic complications has been documented, it has not been widely studied, nor have safety and efficacy been established. Imiquimod should be used cautiously in patients with autoimmune disease. Additionally, its high cost may prohibit its use in some patients. Topical 5-fluorouracil 5% cream25 is sometimes used to treat small, superficial BCCs. It is a fluorinated pyrimidine that "blocks the methylation reaction of deoxyuridylic acid to thymidylic acid. In this manner fluorouracil interferes with the synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and to a lesser extent inhibits the formation of ribonucleic acid (RNA). Since DNA and RNA are essential for cell division and growth, the effect of fluorouracil may be to create a thymine deficiency which provokes unbalanced growth and death of the cell." In properly selected (eg, thin) tumors, cure rates of approximately 80% have been obtained. It is generally applied twice daily and must be used for at least 6 weeks for the treatment of superficial BCC. Percutaneous absorption of 5-fluorouracil is its major limiting factor; it penetrates only 1 mm into the skin. New vehicles that may enhance absorption of 5-fluorouracil are being investigated. One advantage of 5-fluorouracil use is that it can act on BCCs that are not large enough to be seen with the unaided eye. Therefore, it may be used in patients with basal cell nevus syndrome or in individuals prone to develop many BCCs to preemptively treat subclinical tumors. Patients with BCCs that are treated with 5-fluorouracil should be monitored carefully because not all tumors completely respond. Cosmetic results tend to range from good to excellent with the use of 5fluorouracil. Although it is not inexpensive, it does cost less than imiquimod. Interferon alfa-2b has shown some success in treating small (<1 cm), nodular, and superficial BCCs. It is administered intralesionally, 3 times per week for 3 weeks. The recommended dose is 1.5 million units per injection (total of 13.5 million U). In appropriate BCC tumors, cures rates of up to 80% have been obtained. Interferon has not become a mainstay in BCC treatment because of its cost, the inconvenience of multiple visits, the discomfort of administration, and its adverse effects. Flulike symptoms, which are dose related, are common with the doses administered to treat BCCs. Cardiovascular, myelodepressive, and neurologic adverse effects are less common with this treatment than with others. Because interferon is an immune stimulant, it should not be used to treat BCC in transplant recipients or in individuals with autoimmune diseases. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) for BCCs has been used for more than 20 years.26 PDT is the process of using specific wavelengths of light to photoexcite porphyrins that have been applied to neoplastic and preneoplastic cells. This increased energy is rapidly absorbed by adjacent tissue oxygen, causing the formation of singlet oxygen radicals. These radicals rapidly react with adjacent tissue and destroy it. 5-Aminolevulinic acid (ALA-PDT) is the only US Food and Drug Administration approved photoreactive molecule for PDT in the United States, and it is only approved for actinic keratoses. It is photoactivated with blue light for 1000 seconds after 1 hour of incubation. Although its use is off label, PDT has been used for treatment and prevention of BCCs, including patients with immunosuppression and nevoid BCC syndrome. Shallow tumors, such as superficial BCCs, respond most consistently. Surgical excision has been shown to be significantly more effective than ALA-PDT in the treatment of nodular BCC.27 The strongest support for PDT as a modality for BCCs comes with data on thin lesions treated with methylaminolevulinate (used outside the United States), but at least one long-term follow-up trial has also shown surgical excision to be superior.28,29 Various protocols have been followed to achieve varying levels of success—increasing the incubation time, increasing occlusion time, and using longer and/or deeper-penetrating wavelengths of light (eg, red light or pulse-dye laser). Many patients continue to prefer PDT because of its short healing time, excellent cosmesis, and relative affordability. Also see the British Association of Dermatologists Therapy Guidelines and Audit Subcommittee’s clinical guidelines summary, Guidelines for topical photodynamic therapy: update.30 Antineoplastic agents Topical or intralesional antineoplastic agents may be administered depending on the type, location, and stage of the basal cell carcinoma (BCC). 5-Fluorouracil (Efudex, Carac, Fluoroplex) Used topically to manage superficial BCC (not on head or neck). Interferes with DNA synthesis by blocking methylation of deoxyuridylic acid and inhibiting thymidylate synthetase and, subsequently, cell proliferation. Dosing Interactions Contraindications Precautions Adult Apply bid in amount sufficient to cover lesions; apply for at least 3 wk; only 5% strength recommended; therapy might be required for up to 10-12 wk Pediatric Not established DosingInteractionsContraindicationsPrecautionsDosingInteractionsContraindicationsPrecautionsDosingInteractionsContraindicationsPrecautio ns Imiquimod (Aldara) Precise mechanism for superficial BCC unknown. May increase tumor infiltration of lymphocytes, dendritic cells, and macrophages. Indicated for biopsy-confirmed primary superficial BCC (not on head or neck) in adults with normal immune systems. Tumors must not be >2 cm in diameter on certain areas of body. Indicated only when surgical methods not appropriate. Dosing Interactions Contraindications Precautions Adult Apply cream to treatment area (including 1 cm of skin around tumor) 5 d/wk at bedtime for 6 wk; leave on for 8 h, then wash area Pediatric Not established DosingInteractionsContraindicationsPrecautionsDosingInteractionsContraindicationsPrecautionsDosingInteractionsContraindicationsPrecautio ns Interferon alfa-2b (Intron A) Protein product manufactured with recombinant DNA technology. Mechanism of antitumor activity not clearly understood; however, direct antiproliferative effects against malignant cells and modulation of host immune response may be important. Investigational use for nodular BCC. Used in a randomized, placebo-controlled multicenter study (172 subjects). Intralesional injections of 1.5 million U administered 3 times/wk for 3 wk yielded 86% complete-response rate; 29% for placebo. Study included nodular BCCs; similar study did not show efficacy for morpheaform or aggressive BCCs. Dosing Interactions Contraindications Precautions Adult 1.5 million U intralesional injection 3 times/wk for 3 wk Pediatric Not established Basal Cell Carcinoma: Follow-up Follow-up Prognosis Basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) treated incompletely can recur. All treated sites must be monitored after therapy. Individuals with BCC have a 30% greater risk of having another BCC unrelated to the previous lesion compared with the risk in the general population. Patient Education Avoidance of exposure to UV radiation is encouraged to prevent basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Helpful preventive measures include carefully planning outdoor activities before 10 am and after 4 pm, wearing a broad-brimmed hat during outdoor activities, and using sunscreens with sun protection factor of 30 or higher. For excellent patient education resources, visit eMedicine's Cancer and Tumors Center and Burns Center. In addition, see eMedicine's patient education articles Skin Cancer, Skin Biopsy, and Sunburn. Basal Cell Carcinoma: Multimedia Multimedia Media file 1: This translucent pink papule has telangiectases and a crusted erosion, characteristic of nodular basal cell carcinoma. (Enlarge Image) Media file 2: Nodular basal cell carcinoma appearing as a waxy, translucent papule with central depression and a few small erosions. (Enlarge Image) Media file 3: Nodular basal cell carcinoma. Nodular aggregates of basalioma cells are present in the dermis and exhibit peripheral palisading and retraction artifact. Melanin is also present within the tumor and in the surrounding stroma, as seen in pigmented basal cell carcinoma. (Enlarge Image) Media file 4: Scale, erythema, and a threadlike raised border are present in this superficial basal cell carcinoma on the trunk. (Enlarge Image) Media file 5: Large, superficial basal cell carcinoma. (Enlarge Image) Media file 6: Histology of superficial basal cell carcinoma. Nests of basaloid cells are seen budding from the undersurface of the epidermis. (Enlarge Image) Media file 7: Pigmented basal cell carcinoma has features of nodular basal cell carcinoma with the addition of dark pigmentation from melanin deposition. The pigmentation often has the appearance of dark droplets in the lesion, as shown here. (Enlarge Image) Media file 8: This infiltrating basal cell cancer has ill-defined borders and telangiectases. (Enlarge Image) Media file 9: Postoperative wound after Mohs micrographic surgery demonstrates extensive subclinical involvement typical of many infiltrating and morpheaform basal cell carcinomas. (Enlarge Image) Media file 10: Large, scarlike morpheaform basal cell cancer. (Enlarge Image)