It is to be supposed that all scientific men accept, at - PhilSci

advertisement

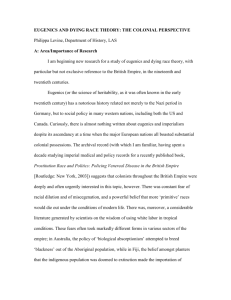

Comments on Paul It is to be supposed that all scientific men accept, at least in theory, the view that the advancement of biological knowledge will ultimately be of service in the practical affairs of mankind; but there can be little doubt that most would feel some embarrassment if their views had to be made the basis of practical, and therefore controversial, policy. There is good reason for this; for scientific men, no less than others, imbibe before their profession is chosen, and perhaps later, the same passions and prejudices respecting human affairs as do the rest of mankind; and while the standard of critical impartiality necessary to science may, perhaps, be easily maintained, so long as we are discussing the embryology of the seaurchin, or the structure of the stellar atmosphere, it cannot be relied on with confidence in subjects in which these prejudices are aroused. R.A. Fisher: The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection, 2nd rev. ed., ch. XII, p. 275 I am interested in the way in which the history of a discipline is, and is not, constitutive of that discipline--I imagine it to be somewhat like the way in which the history of a species is, and is not, constitutive of that species. One of the problems in thinking about this question is that contemporary practitioners of a discipline often tell what purport to be historical narratives about their discipline. These narratives may be demonstratively one-sided, selective or, in the worst case, completely fabricated. One role for history in this circumstance is to test these narratives against a serious phylogenetic reconstruction of the discipline, in the case before us, human genetics. Because I find this interesting, and because there are two commentators, I am going to focus my attention on Pt. III of Professor Paul's paper. Diane Paul is there interested in the way in which contributors to the contemporary debate over the pros and cons, promises and dangers, of genetic engineering tell historical narratives to bolster their argument. 2 One immediate question is how Parts III and II of her paper are connected to each other. Is Part II providing a more nuanced and balanced picture of the eugenics movement(s), for comparison with the ‘contested uses of history’ discussed in Part III? If so, less attention needs to be given to the forward-looking science fiction of the eugenicists she discusses—as amazing as it is--and more to the actual social recommendations and historical activities of members of (to cite two) the Eugenics Laboratory of the University of London or the Eugenics Record Office at Cold Spring Harbor; or on serious policy-oriented discussions of the pros and cons of eugenics found in works such as W. E. Castle's Genetics and Eugenics, published in 1916 by Harvard University Press, or the later chapters of Ronald Fisher's The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection published in 1930 by Oxford U. Press. That is, we need to compare the claims about the history of eugenics in the narratives told today with what actually happened, rather than with utopian or apocalyptic visions of a eugenically shaped world. A second question I have emerges from the first two paragraphs of Part III of Paul's paper. She begins by noting that 'as late as the 80s' it was not common to oppose advances in the application of genetic engineering to medicine or reproductive technology simply by branding them as 'a new eugenics'. If the term was used at all, it was not used pejoratively. Now I would like first to know more about the scope of that claim and, given that the scope of the claim is defined, how good our evidence is for its general truth with respect to the defined domain. But more interestingly, we are told that by now the situation has changed, and "in popular and even most academic discourse, to label a practice "eugenics" is thereby to denounce it" (p. 9). About this I also would like to have both the scope of, and the evidence for, the claim more clearly defined. But 3 supposing, that being done, it turns out that there was a change of this kind, I would be interested in hearing from Diane Paul why she thinks this change occurred. Be that as it may, she wants to claim that simply labeling a use of genetic engineering in human reproduction as 'eugenics' has taken the place of argument. One is no longer required to explain what is harmful about the practice, provided you have convinced people that it is 'eugenics'. (It is important to put it this way, since from a eugenicist's standpoint, a great deal of the medical potential of genetic engineering may be seen as having a negative, rather than a positive, impact on the human gene pool.) With respect to the role of "the histories that typically accompany these discussions", Paul claims that an implication of most is that eugenics is by nature coercive. Most of page 10 of the paper consists of quotes from people arguing, or more often simply asserting, the value of personal autonomy in reproductive and medical decision-making. She tells us that these quotes are sufficient to show us that tales "that equate eugenics with racism and compulsion and star jack-booted Nazis" aid the enthusiast for genetic engineering in two respects. 1. If they do not advocate coercive genetic engineering, then it is unfair to brand them as eugenicists. 2. They serve as cautionary tales with the moral of keeping human genetic engineering out of the hands of state. It should be pointed out, however, that there are many proponents of genetic engineering who are not opposed to government regulation of the practice--I suspect the NIH is full of such people. So the most one can say here, I think, is that such histories 4 may serve the interests of advocates of a free market approach to the production, provision and the consumption of these technologies, not to enthusiasts in general. Interestingly, Paul claims that the very same tales are used by critics of human genetic engineering as well. She quotes Ted Peters' summary of the logic here: Germ-line modification can be associated with eugenics Eugenics can be associated with Nazism ________ Advocates of germ-line modification can be associated with Nazism There is no need here to point out how bad that argument is--at any rate, Peters is summarizing what he claims to be the argument of a Council on Responsible Genetics position paper, and I have no confidence that Peters is being entirely fair to the argument. But I am interested here in the claim that we have the same history being appealed to by both opponents and proponents of human genetic engineering. In the remainder of Prof. Paul's paper, I don't find evidence for this claim. In the quotes from opponents and in her summaries of their views, I don't see historical associations with Nazism playing any role at all. There is a negative view of eugenics, and an attempt to tar the use of genetically sophisticated reproductive technologies with the eugenics brush. But it is a different aspect of eugenics that is worrying these opponents. It is not the association of eugenics with a coercive dictatorship that is the concern. It is the implication, built into the term 'eugenics' by its very etymology, that there is an 'ideal person' that should be the aim of the selection process. So we hear from the opponents of bio-engineering concerns about "self-appointed arbiters of human excellence" about parents desiring "a certain kind of child", about judgments that "some genes are better than others", "selecting humans of value and non-value", "fostering an unhealthy preoccupation with perfection". 5 And Paul's own history backs up this concern--take a look at those claims by Wallace, Spencer, Galton, Haldane or Trotsky. Moreover, this is a worry that has been raised by critics of the eugenics movement since the 1860s. One of the results of looking at the writings of eugenicists throughout the post-Darwinian period is that they come in two varieties--the glass-half-full and the glass-half-empty variety. Is the aim of eugenics to prevent a looming genetic overlaod and crash; or is it to build a more perfect human gene pool? In the following quote, from the 1st edition of Dobzhansky’s Genetics and the Origin of Species, he portrays the glass-half-empty variety. I suppose he has Müller in mind. The eugenical Jeremiahs keep constantly before our eyes the nightmare of human populations accumulating recessive genes that produce pathological effects when homozygous. These prophets of doom seem to be unaware of the fact that wild species in the state of nature fare in this respect no better than man does with all the artificiality of his surroundings, and yet life has not come to an end on this planet. The eschatological cries proclaiming the failure of natural selection to operate in human populations have more to do with political beliefs than with scientific findings. Looked at from another angle, the accumulation of germinal changes in the population genotypes is, in the long run, a necessity if the species is to preserve its evolutionary plasticity. [1937, 126] In sum, I see tales about the history of eugenics playing two distinct roles, corresponding to two aspects of the concept. Galton had defined eugenics as "the study of agencies under social control that may improve or impair the racial qualities of future generations, either physically or mentally." What worries some people in that idea is that 6 'social control' will be used to achieve eugenic goals. What worries others is the implicit assumption that there is a single set of genetically controlled characteristics that define 'improvement of the racial qualities, either physically or mentally'. Some worry about the means, some worry about the ends. They are both worries about eugenics, but they are not the same worries, and they are not supported by the same narratives. And the history of eugenics, which must include a history of its critics, reveals some who shared eugenic ideals but were opposed to their achievement by coercive means, and others who thought that the ideals were misguided. And a group we haven’t talked about, which includes Dobzhansky and many other members of the neo-Darwinian synthesis, thought that proponents of eugenics completely misunderstood the genetics of populations. James G. Lennox History and Philosophy of Science University of Pittsburgh