Sand tiger sharks in New England

advertisement

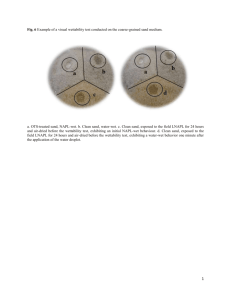

The sand tiger shark (Carcharias taurus) is a large coastal species that ranges from the Gulf of Maine south to the Gulf of Mexico along the east coast of the United States. They are commonly found in inshore waters ranging from 6 – 600 feet in habitats such as surf zones, shallow bays and estuaries, rocky and coral reefs and near shipwrecks. Sand tigers can be identified by the presence of two large dorsal fins, a large anal fin, large thin teeth, dusky spots along the side of the animal and black coloration at the tips of the fins. QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. Sand tiger sharks in New England Sand tiger sharks are seasonal visitors to New England waters during the warmer months of June – November. In the early to mid 1900’s sand tiger sharks were considered to be one of the most common shark species in New England waters and both commercial and recreational fishermen caught large numbers of individuals as far north as southern Cape Cod Bay. During this time, a directed commercial fishery was established in Nantucket Shoals, however, this fishery was short lived due to rapid depletion of the local stock. Unfortunately, increased fishing pressure on the species along the entire east coast of the United States during the mid – late 1900’s severely depleted sand tiger populations, including those around New England. In 1997 as a precaution to stop fishing mortality, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) prohibited sand tiger sharks from being targeted and retained in both commercial and recreational fisheries. In 2005, Massachusetts state law also prohibited the targeting and retention of sand tiger sharks in state waters. During the last few years, an increasing number of juvenile sand tiger sharks are being incidentally caught in Massachusetts coastal waters, particularly along the south shore in Plymouth, Kingston, Duxbury (PKD) Bay. Interestingly, occurrence of sand tiger sharks in this region appears to be a relatively new phenomenon as local fishermen claim they have never seen this species in this region until recent years. Our Research Over the last few years the Massachusetts Shark Research Program (MSRP) has worked with commercial and recreational fishermen in the region to investigate the presence and abundance of sand tiger sharks in Massachusetts state waters. Based on recent catch records, most of the sharks inhabiting the region are young of the year (newborn) individuals. While the lack of large females in Massachusetts precludes the use of Plymouth, Kingston, Duxbury Bay for parturition (birth), it appears as though these coastal waters provide secondary nursery habitat for sand tigers that move north from southeastern pupping grounds. Given their increasing numbers in PKD Bay, this embayment may be the most important secondary nursery area for this species north of Delaware Bay. At present, the MSRP has a study underway goaled at investigating regional movement, habitat use and the effects of capture of sand tiger sharks inhabiting New England coastal waters. Working in conjunction with local commercial and recreational fishermen, the MSRP is actively tagging sand tiger sharks with acoustic telemetry tags to quantify both regional and large-scale movement patterns and habitat use. Each acoustic tag emits a unique coded signal that can be picked up by a series of underwater receivers (listening stations) located in fixed positions within Plymouth, Kingston, Duxbury Bay and Massachusetts coastal waters. If a shark swims within range of a receiver, the unique signal of its acoustic tag will be logged and stored as a data point on the receiver. Periodically the data logged by the receivers will be downloaded onto a computer and analyzed to generate information on regional movement, habitat use and overall ecology. Fortunately, receiver arrays maintained by other researchers in other regions (i.e. Delaware Bay and North Carolina) are capable of detecting fish tagged in New England waters, allowing for the potential to learn about large-scale movements of these young fish. Data to date In September 2008, three sand tigers were tagged with acoustic tags within PKD Bay. In the few weeks during which they remained in the Bay, various receivers logged 2,727 detections and provided some interesting information about habitat utilization. Interestingly, one fish tagged in the Jones River in early September was detected in a receiver array near the entrance to Pamlico Sound (Cape Hatteras, North Carolina) during mid-January. During the 2009 season, the MSRP will continue tagging sand tiger sharks with acoustic transmitters within PKD Bay. Working in conjunction with the Jones River Environmental Heritage Center, the MSRP also hopes to periodically maintain captive sand tiger sharks in a holding tank located at the Jones River Landing for experimental purposes as well as for public outreach. If you would like more information about this project or would like to report information about sand tiger shark occurrence in Massachusetts waters, please contact the Massachusetts Shark Research Program at 508-910-6329 or 508-693-4372. References Bigelow, H. B. and W. C. Schroeder. 1953. Fishes of the Gulf of Maine. Fishery Bulletin of the Fish and Wildlife Service. 53:74 Gilmore, R.G., J.W. Dodrill, and P.A. Linley. 1983. Embryonic development of the sand tiger shark Odontaspis taurus (Rafinesque). Fishery Bulletin 81:201-225. Skomal, G.B. 2007. Shark nursery areas in the coastal waters of Massachusetts. American Fisheries Society Symposium 50:17-33. Acoustic data from two sand tigers (ST1 and ST 17) tagged in PKD Bay. ST 17 136 detections, 29.5% Cape Cod Bay 198 detections, 26% Duxbury Bay 119 detections, 43% ST 1 Kingston Bay 119 detections, 10% Plymouth Bay 285 detections, 46% Plymouth Harbor Warren Cove 250 detections, 40.5% Preliminary data on habitat use of two sand tiger sharks tagged in different areas of PKD Bay. Data are presented from acoustic receivers (designated by white circles) that logged the largest number and percentage of total detections for each fish, thus, the areas where each fish spent the majority of its time within the array. Tagging locations are indicated by appropriately colored circles.