The Book of Job: Loss, Suffering, and Pastoral Care

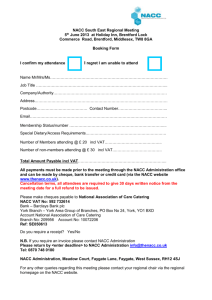

advertisement

Audio Conferences October 2009 “The Book of Job: Loss, Personal Suffering, and our Pastoral Care Ministry” Sr. Dianne Bergant, CSA 1. LITERARY STRUCTURE OF THE BOOK A. Prose Prologue: Chapters 1 & 2 – the trials of a just man: “My servant Job” B. Poetic dialogues between Job and visitors: Chapters 3-37 – – the challenge of retribution: Why do the innocent suffer? C. Poetic speeches of God: Chapters 38-42:7 – – the mysteries of creation: Where were you when I created the universe? D. Prose epilogue: Chapter 42:7-17 – - ‘Now I have seen you.’ 2. EXPANDED OVERVIEW OF CONTENT OF THE BOOK Chapters 1 & 2 Most people know the story of the patient Job, a righteous man who lost all of his possessions and then his children through consecutive tragedies and was later physically stricken with disease. Despite these misfortunes, Job remained constant in his dedication to God. In the end, he received his fortune back, doubled. However, this is not an accurate description of Job. The major portion of the book describes an angry man, one who rejected the advice of his visitors and who accused God of unfair treatment. Chapter 3 There are times when we are able to bear crushing hardship - at least for a while. It is then that we reach deep within ourselves and call on reserves of strength and patience. We might tell ourselves: ‘I can get through this if I just keep my wits about me.’ But, how long can we do this? How much strength and patience do we really have? Knowing what can happen to us during extensive and prolonged hardship, we should not be surprised that Job eventually exhausted all of his patience and launched out into an impassioned string of curses. Chapters 4-37 The greater part of the Book of Job consists of three cycles of dialogue between Job and Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar, the three men who came “to give him sympathy and comfort” (Job 2:11). Rather than consoling him, each man advises Job to confess his guilt, for they believe that his hardships are the consequence of some wrongdoing. , Job insists on his innocence. Each cycle of dialogues contains the same pattern: accusation of a visitor followed by Job’s defense. Space prevents us from examining all of them. A careful look at only one cycle will enable the reader to capture the gist of this exchange. Chapters 38-42:6 The last words in Job’s final declaration of innocence pose a challenge to God: “Let the Almighty answer me” (31:37). These words of Job the plaintiff constitute the subpoena for God the defendant to appear in court. Will God comply? Will God answer and thus give evidence of being aware of what has been happening in Job’s life? Or is God as disinterested as Job fears? And what if God does answer? Will The Book of Job: Sister Dianne Bergant, CSA NACC October 2009 Audio Conference / Page 1 there be words of understanding and comfort, or words of anger and condemnation? The fact that Job ends his plea in this way indicates that he has not given up hope that justice will prevail. Chapter 42:7-17 Job’s dilemma seems to have been resolved, but there are so many issues that still must be explained. Job comes away with new insights gained through his contemplation of the cosmos and various creatures of the natural world. However, does God ever let him know the reason for his misfortune in the first place? What are we to make of the advice given by Job’s visitors? Does it stand, or is it shown to be inadequate? And finally, what about Job’s family? They seem to have perished simply in order to teach Job a lesson. Is that fair? 3. ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND a. Did this really happen? Was there really a man named Job, or is this a story of fiction? Actually there is another way of describing the character of this intriguing book. A story can be true without being historically factual. It can describe an event that most, if not all, people experience, without including specific details that might apply to only a few. The story of Job is this kind of story. It is about a person of integrity who tries to live an upright life yet who is forced to endure great misfortune without being able to understand why. Who cannot identify with Job? The book itself is made up of prose and poetry. Chapters 1 and 2 and the last eleven verses of Chapter 42 form a kind of prose framework. Some people think it was originally an old folktale. It is here that we find the picture of the patient Job. However, the real drama of the man’s struggle with misfortune unfolds in the poetic dialogues found in Chapters 3-42:6. It is there that we see him grapple not merely with the suffering itself but also with his inability to understand why God has afflicted him. It is also there that his dilemma is somehow resolved and he arrives at a state of acceptance. b. Who the devil is the satan? A mysterious figure called ‘the satan’ appears in the opening pages of this book. Since most translations have “Satan,” we presume that this is the proper name for the evil one whom Jesus condemns (Matt 4:10; Mark 1:13; Luke 10:18: John 13:27). However, the definite article “the,” is included in the Hebrew text, indicating that this is simply an identifying noun, not a personal name. The satan, found in the heavenly court, along with the other servants of God, charged with “roaming the earth and patrolling it.” He challenges God, not Job, to test the authenticity of this righteous man. He has no power himself to inflict Job. Some commentators maintain that ‘the satan’ is merely a literary ploy of the author of the book, a character who can be blamed for Job’s misfortunes. This was a way of taking the responsibility for Job’s unfair treatment off of God, who was thought to be all-good. By the time of Jesus, the diverse traditions about the tempting serpent in the garden of Eden (Gen 3:1), the challenging satan of this book, and the morning star that fell from heaven (lucifer in Latin, but really a reference to the King of Babylon in Isa 14:12) all come converge into the figure of the devil who is the source of evil in the world. c. Get over it! Nobody likes a cry baby. When we encounter one, we might be tempted to say: “Get over it!” But Job is not a cry baby. He is not sniveling or indulging in exaggerated self-pity. We the readers know that he is an innocent victim of an agreement made between God and the satan. People down through the centuries obviously have thought that his cries were warranted and his anger justified or they would not have cherished his story as they have. Because we sympathize with his grief, we would never think of saying “Get over it!” Still, how are we to understand his manner of complaining? The Book of Job: Sister Dianne Bergant, CSA NACC October 2009 Audio Conference / Page 2 There is an ancient form of complaining that is known as lament. Most people may not realize it, but the largest category of psalms in the Bible consists of laments. In it, the one suffering cries out in complaint, describes in very graphic figures of speech the nature and degree of the distress, and hopes that some relief will come shortly. It may not always sound like Job is hopeful, but he never really despairs d. What did I do to deserve this? Who has not asked this question? Who has not felt at times that certain misfortune is unfair? Why do we think this? It is because we believe that there is a ‘cause and effect’ relationship between our actions and the circumstances of our lives. We learn this simply by living. If you eat sour apples, you could get sick; drinking a glass of cold water will refresh you on a hot day. ‘Cause and effect’ usually helps us understand how life works, and so we expect it always will explain things. When we experience disappointment, or discomfort, or significant distress, we readily ask ourselves: What did I do to deserve this? This principle called retribution, the idea that good is rewarded and evil is punished, is the basis of our theory of justice. From it we conclude that the kind of behavior that produces pleasure or happiness is the path of life we choose to follow. Conversely, whatever results in displeasure of unhappiness is behavior we want to avoid. From this we presume that we will get what our actions deserve. e. A ‘WOW’ moment is more than an ‘ah-ha’ experience. Some people today make a lot of what they call an ‘ah-ha’ experience. By this they mean that they have had an enlightening experience and now they understand something. These are wonderful occurrences and they can often move us to a much deeper level of living. However, there are some experiences that are so profound that all we can do is stop where we are and what we are doing and stand in a kind of ecstasy (the word means to stand outside of oneself). These are ‘WOW’ moments. They are more than intellectual enlightenment. No words can describe them. An experience of God, known as a theophany (from the Greek theo – God, and phaínō - to appear) is such an experience. Because of the majesty of God, people might respond to a theophany with awe or fear. In these circumstances the first words they often hear are: “Fear not!” (God to Abram – Gen 15:1; the angel to Mary - Luke 1:30; Jesus to his disciples – Matt 14:27). Knowing that the experience of God itself may be more than Job can endure, he is told to prepare himself as if for battle (the Hebrew word for ‘man’ used here really means ‘strong man’ or ‘warrior’ - 38:3; 40:7). In a theophany, one experiences the awesomeness of God and the limitations of human nature in the face of it. f. Educate: To fill with information? Or to bring out knowledge? Today there are many theories of education - inductive, deductive, experiential, to name but a few. One well-established approach is known as the Socratic method, so called after the great Greek philosopher. We are told that he would walk up and down asking questions, not so much to test what the students had learned as to enable them to bring out what they knew. This is the approach to teaching that God uses with Job. A second pedagogical technique appears in God’s questioning. It employs some aspect of the natural world to teach something about human life. The story of the hare and the tortoise is an example of this technique. The proverb “Go to the ant, O sluggard” (Prov 6:6) is another. In the book of Job, God points to the wonders of the universe and the care of animals to lead Job to see that much in his life Job will never understand or be able to control. Job’s final response shows that he learned these lessons well. This means that God succeeded not in filling Job with information but in enabling Job to reach deep within himself and bring out what he now understands. The Book of Job: Sister Dianne Bergant, CSA NACC October 2009 Audio Conference / Page 3 4. MAIN THEMES a. Retribution: goodness is rewarded; evil is punished b. Theodicy: questioning the justice of God c. Cosmology and mystery d. Major theme: Innocent suffering? Unquestioning acceptance? Incomprehensibility of God? Mystery? The Book of Job: Sister Dianne Bergant, CSA NACC October 2009 Audio Conference / Page 4