Navigation among perilous texts - east

advertisement

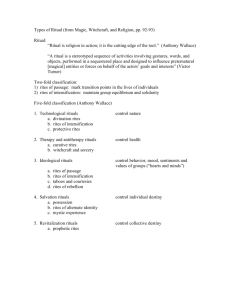

Yuri Rozhdestvensky’s Law of Accumulation and Non-Destruction of Culture Definitions are boring, and any scholarly argument centered around a definition is suspect. However, there is one sense in which a good definition is important – it is the sense expressed by Confucius: "If the name is wrong, the speech does not obey; if the speech does not obey, the action does not take shape. But if the name is correct, then the speech obeys; and if the speech obeys, the action takes shape". The same idea is explored in Plato’s Cratylus, where Socrates says: “Regarding the name as an instrument, what do we do when we name?… Do we not give information to one another, and distinguish things according to their natures?… Then a name is an instrument of teaching and of distinguishing natures, as the shuttle is of distinguishing the threads of the web… Then, Hermogenes, not every man is able to give a name, but only a maker of names; and this is the legislator, who of all skilled artisans in the world is the rarest”. We can shape our action and discuss high and low culture if we first find a good definition for both. Following the tradition of Plato and Confucius I would like to discuss the definition of culture offered by one of rare skilled “legislators” of culture studies, the Russian scholar Yuri Rozhdestvensky. In his definition there is no such thing as “high” or “low”. But before I present that theory, let me say a few words about its author. Yuri Rozhdestvensky is not known in the US. During his life, Rozhdestvensky’s works have been published in German and Chinese. As often happens, his students began to worry about translation after their teacher died, so now English translations of a few of his books are in the works. Undoubtedly, it will be interesting for the Western linguistics to discover this philosopher, linguist, educator and communication theorist. Rozhdestvensky started his scholarly career from writing on Chinese grammar; his second Ph.D. involved the study and comparison of 2,000 grammars and established several language universals; he then moved on to comparative study of Chinese, Indian, Arabic and European rhetorical traditions. However, discourse and communication interested Rozhdestvensky not as a pure science but only as long as they could be put to use to serve the needs of his country and his language. For example, one of the pressing needs of Russia as a multi-cultural country is diversity and development of ethnic and linguistic minorities. Rozhdestvensky advocated for internal (domestic) oriental studies – he submitted proposals to the government that warned about the precarious situation in the Caucuses. According to him, rich economic reserves of the region – for instance, oil and gas – conflict with its unsatisfied spiritual needs in education. The misbalance between material and spiritual culture needed to be addressed. The Russian government authorized Rozhdestvensky to conduct negotiations after the first Chechen war, and in devastated city on poor paper the Chechens published Rozhdestvensky’s brochure on rhetoric. Rozhdestvensky said, “Their eyes shone when I talked about education”. A group of scholars under Rozhdestvensky’s guidance was creating a thesaurus for education in Chechen schools, and the university in Grozny was translating that thesaurus into the Chechen language, creating necessary vocabulary in the process of that work. After the war resumed, the dean of the Chechen university fled to Russia and stayed at Rozhdestvensky’s home for a while. The project was killed in that war, but the need remains to address the unsatisfied spiritual and educational need of the people of the Caucuses. My teacher was a unique person. He was very ironic but also, or maybe because of that, very accepting of others. His house was always full of us, students. He cooked huge pots of meals and used to say that the tradition of Moscow University has always been for the professors to feed the 1 students. He conducted seminars at his Moscow home and at his country house, and at every party made every guest make a speech, turning it into a competition in inventiveness. His wife presided over that incessant flow of students, colleagues and friends. The way he advised sophomores on paper topics was, “Tell me, lovely creature, what did your parents teach you when you were little?” I answered, “Dancing and figure skating”, and Rozhdestvensky said, “See if you’d be interested in exploring similarities between language and movement. Those are the only human sign systems that use no other tools except human body – there must be some fundamental similarity in them”. Eight years later I was defending a Ph.D. thesis comparing methods of teaching native language and foreign language with the methods of physical training. A good friend of mine, when asked “Tell me, lovely creature, what did your parents teach you?” said, “To love Turgenev”, and eight years later she defended a Ph.D. on literary styles, parody and composition of literature readers for schools. On his deathbed, when the priest was administering the final rites, Rozhdestvensky said, “I have completed my task”. One of Rozhdestvensky’s areas of research was Culture Studies, and this returns us to definition of culture and the style changes occurring between generations. In his Introduction to Culture Studies Rozhdestvensky defines culture as events, facts and artifacts that are relevant for future generations because they provide rules, precedents and best practices. In that sense culture does not include daily activity or new works of art. New artifacts or events appear; then they are critiqued and evaluated by experts; then they are included in museum or other appropriate collections; they become systematized and codified. Then they become part of culture. The process of selection, description, codification is the process of formation of culture. In that sense there is no “high” or “low” inside culture: if something is low quality, it does not become selected by experts and does not become culture. It remains on the level of daily exploits, vanity and handfuls of wind, and eventually sinks into oblivion. The difference between culture and “daily exploits” is illustrated by the difference between Mozart and Salieri: the former remained valid for future generations, and the latter was widely popular in his time but apparently lacked a secret ingredient that would make his music unique and thus everlasting. Once an event or work of art has become part of culture, it stays forever. This is the Law Of Accumulation And Non-Destruction Of Culture. According to this law, new facts and artifacts do not cancel out other facts that are already included in culture; facts and artifacts belonging to one time period form a stratum; new strata enhance and invigorate old ones. For example, preliterary societies use animals as a source of power (horses, oxen, donkeys, mules, etc); ancient civilizations add mechanisms (windmills, water mills) and keep and improve, through selection and breeding, the breeds of animals used as source of power; modern civilization adds electricity and nuclear power and keeps animals as a source of power, enhancing that old stratum through attributing entertainment value to it (e.g. hay rides and sleigh rides at $3 per adult at a historic farm). For another example, every preliterary society has oral speech, news and folklore; when writing is invented, old genres become invigorated and grow with the help of the new technology: folklore can be recorded and stored, oral dialogue can involve exchange of notes, news can be recorded and spread confidentially, public speeches now may be written down before they are pronounced, and there is an expectation of greater uniformity in grammar even in traditional oral genres. With the invention of the printing press manuscripts receive standard orthography, footnotes, tables of content, i.e. printing adds on to the achievements 2 of the written stage; and certainly with the introduction of electronic means oral genres are not cancelled out but are enhanced (we can now talk on the phone or even a videophone), written genres are enhanced (documents, letters and memos receive additional formatting and can be exchanged faster) and printed genres are enhanced (e.g. many texts can be accessed easier, searched for specific expressions and abundantly commented). So contrary to what the new generation thinks, they are not starting anew; they are going to add to the previously existing platform on which they stand. An important task of society is to acculturate the young. The degree of cultural knowledge differentiates generations. It is confirmed in the initiation rites that the young ones pass. All peoples have initiation rites to mark a person’s passage into the category of adults; all of those rites include a course of study and some testing that needs to be completed before the rites are administered. The new generation needs to be “assimilated” into the culture of their parents in order to be able to function. In the light of the Law of Accumulation and Non-Destruction of Culture it is clear that no matter what the Animaniacs generation says about the obsoleteness of our “old” “high” culture, it is our role as educators to assimilate them into it, even if it means teaching “the dead white guys” (who have already invented a lot of bicycles, to a great surprise of most young students). Clearly, each generation has a characteristic behavior; each generation re-assesses “old” culture that we provide for them. What exactly do they re-assess? How are they different from us? Rozhdestvensky classifies culture as follows: Physical Culture Hygiene Childbirth and birth control Games Rites Diet Safety Etc. Material Culture Animals Plants Soils Buildings Tools Roads and transportation Communication Technology Spiritual Culture Morality Tribal Religious Professional National Ecological Beauty 3 Applied art Non-applied art Knowledge Information Wisdom Science Interestingly, the new generations almost never criticize or reject the physical culture of their society: they accept uncritically what coaches and teachers present to them; the innovations in physical culture come from the old generation – teachers and coaches. Material culture is not so lucky: the new generations will re-assess existing agricultural practices, technologies, buildings, materials, etc. and try to approach them differently, or introduce new additions. However, the young ones are usually respectful of the old generation’s material culture because they need to use it – they live in our houses and drive in our cars until they can invent something better. The worst lot falls to spiritual culture: learning it is a long and dull process, so it is easier to start creating your own, anew, rejecting the “obsolete”. My 17-year old sister hasn’t watched any of the movies of my youth, and when I suggest a movie that was famous 20 years ago she says, appalled, “But it’s OLD!” Every new generation goes through this cycle: they create their own new works of art and behavior precedents. For instance, modernism negated preceding culture and claimed to start a “new era”. They create a new style, and call it culture. In this sense, every new style is, to a degree, demonstration of ignorance! Often new styles are based on inventions of a new technology or on an innovation in division of labor. Another definitional tendency is to use the term culture for the process of creative work, especially in entertainment and arts, where the artist’s individuality is present – i.e. to identify culture with style. The problem with the process of invention is that it produces a lot of scrap. Current new generation is at a disadvantage, because the process of creative scrambling around becomes amplified by mass media. Before a work of art, or a new genre, or a behavior style can be properly critiqued, it is already advertised and copied. But what if it is at best mediocre? It litters the wavelengths, and only after that is discarded. Before it is discarded it has already made good taste retreat. Fortunately, not everything that is being experimentally created in the new style will fall into oblivion. While most experiments will be classified as pathetic scrambling around, a few artifacts or acts will eventually be sorted out as worthy of becoming part of culture in the eternal sense. There is a dialogical relationship between “real culture” – things that have already been selected as rules and precedents – and current goings-on of creative work. They feed off each other: new items are born in the imagination and intuition of an artist; those new items are successful if they find their place in relation to the tradition; tradition is enriched by new items. It is the role of experts to determine what products of the new aesthetic should become part of tradition, i.e. overall human culture (for the future generations to try to overthrow). It is the role of educators to include those items in the curriculum and to adjust curriculum accordingly. It is certainly the role of educators to preserve in the curriculum everything important that has been a part of culture. Obviously, the aesthetic of the new generation is influenced by mass media and, as said above, by the new technology – the electronic one. Mass information, mass culture, mass advertisement, mass 4 games and various computer systems need to be discussed in terms of their relationship to the law of accumulation and non-destruction of culture and in their relationship to style. Rozhdestvensky describes them in his Philosophy Of Language And School Curriculum. Mass information is created based on division of labor (financing organizations determine the direction, information agencies provide the material, journalists write, editors combine pieces, etc.) and is characterized by daily variation, timeliness and factual correctness. It creates an ever present backdrop of people’s life – we are used to constantly receiving news collages. The collages of mass information are designed to make an aesthetic or emotional impact, and thus they are not eligible for a critique by logic. The only part of mass information that can be addressed with logic is the information strategy. However, information strategies are not immediately obvious; to isolate and describe them one needs to use special analytical tools, like content analysis. Information strategies of mass information need to be constantly evolving. This law of evolution is caused by the recipients’ satiation: when themes and commentaries have been repeated in mass media to the level of satiation, recipients begin to reject them. Then a new information strategy needs to be developed. Because mass information has this daily nature with quick turnaround, it is not a cultural type of activity – it is mainly concerned with daily exploits and is not built to last. If I am not mistaken, in Greek language the newspaper is called, appropriately, ephemerida. Mass information does, however, influence the style and methods of education. It does so through mass culture and mass advertising. Mass culture is a curious formation. It is a system of entertainment that is based on quick style changes and is linked to the changes in mass information strategies. It consists of mass spectacles organized by professionals on one end of the continuum and amateur talent shows on the other, with many intermediate stages. Mass culture is similar to the military and to sport in the following sense. Every human society functions using 16 semiotic systems: 1. Language III. APPLIED ART II. NON-APPLIED ART crafts architecture costume dance music pictures 3. Rites 4. Games commands measures reference points signs omens future-telling IV. MANAGEMENT I. PROGNOSIS 2. Count These semiotic systems are present in every society, though they may be fleshed out differently – e.g. one may use taro cards, turtle shells, stochastic calculus or crystal balls to predict weather, stock market behavior, war victory, etc. In the course of society development the military separated into a pocket of activity that is serviced by all semiotic systems. It may even be called society in 5 miniature, with its own forms of art, games, prognosis and management. The same principle applies to sports: in the course of society development it grew into a field serviced by all semiotic systems. In the 20th century mass culture became a third field in human history to be gemmated into a pocket with its own rituals, language, management, prognosis, etc. However, unlike the military and sports, mass culture is inexorably linked to mass information (being dependent on TV, newspapers, radio) which is by definition not a cultural but a transient text. This makes mass culture also a transient phenomenon oriented at the style of one particular generation (though does not preclude a possibility of a timeless piece being created in that field). Mass advertisement is, obviously, also dependent on mass information and is influenced by its collage and figurative structure. Its goal is to cause a desire in recipients. To cause a desire it is necessary to use semiotic signs to appeal to the rational, the emotional and the subconscious. This is why mass advertisement turns to research in animal psychology. It addresses all levels of zoological behavior in humans: tropism and taxis, which are behavior patterns common to all forms of life, e.g. viruses and bacteria moving to parts of the Petri dish that contain more broth; knee-jerk reflexes, which is a behavior present in all animals with a nervous system; instincts, i.e. innate complex behavior programs, like those determining reproductive or social behavior in insects; conditional reflexes, like salivation of Pavlov’s dogs; rational behavior demonstrated in an individual’s learning, e.g. a mouse memorizing through trial and error the shortest way to food in a labyrinth; and finally conscious behavior, i.e. solving new problems in new situations, e.g. a cat rolling its toy under a closed door and walking around through a second door to reach the toy. Common to all advertisement is attracting attention through paradoxical images. Also common to all forms of advertisement is the change in the notion of “value”: from a philosophical and ideological notion it has changed into an object of desire. Advertisement creates values in the sense that it causes recipients to desire additional objects. Mass games are lotteries, TV word-guessing games, trivia games, erudition competitions, and others. While games have folk origin, mass games depend on mass information. The games include prizes, i.e. financial interests, not even excepting children athletic competitions. This creates an atmosphere of gambling and chance, where taking a risk or subjecting oneself to public embarrassment may suddenly result in a windfall. Many such games are fairly plebeian, e.g. eating competitions or public undressing and dressing; all are based on a desire of a chance reward. Amplified by mass media they create an atmosphere of primitiveness and of possible luck. Together, mass culture, mass advertisement and mass games produce the feeling of liberation and a state of mind in which success is necessary, is achieved through a gamble without effort, and can be achieved through a new gamble if this one didn’t work out. This combination contrasts with the scary dark news of mass information. On the other side of the screen there are someone else’s disasters like airplane crashes, famines, arms race, etc.; those gloomy events underscore the joy of entertainment, game, freedom and intuitive good guesses. Life, ideally, is shaped as a sequence of stages: carefree babyhood; studying for the sake of future earnings; earnings; and, thanks to the earnings, carefree idleness after retirement. This system has no room for spousal fidelity, love towards parents, tending to children. People steeped in mass media are seized by a desire to acquire valuables and by the fear of losing those valuables as accidentally as they were acquired. Beyond such state of mind there is real life with family, creativity, professional achievement. This serious life requires consistent work and real feelings; it has its foundation in real culture, i.e. in rules and precedents selected in history. Productive activity is impossible for individuals limited to mass media culture oriented at quick changes of fashion and not familiar with real culture. Of all 6 new technologies, computer programs reflect real productive activity. Computer programs can participate in almost all semiotic systems that service human culture, e.g. computer design (applied arts), computer graphics and music (non-applied arts), computer games, computer simulation (prognosis). Two semiotic systems do not use computer programming: rites and dance. Those two are not eligible for computer help because their material carrier is the human body which so far cannot be blended with computer hardware. Thus there is an opposition between transient, fleeting products of mass media and real culture that forms the foundation of real life. One may say that the aesthetic of the new generation and modern development of culture have been influenced by the tragic mood of mass information and the euphoric mood of mass entertainment. Together they produce a few effects. Parenthetically, we should not count acquisitive impulses and other physiological effects among serious cultural shifts: they are better classified as curable diseases of mass media consumers; the cure lies in turning off the TV for a few days. Valid modern developments include these: heightened interest in religion as the bearer of more solid moral values (people need an anchor, after all); heightened interest in health and activity in the adulthood and old age (valeology); heightened interest in games and winning (game-ology?); heightened interest in world culture, its logic and typology (culture studies). Rozhdestvensky calls the former three “stylistic interests”. The latter appears because it may be helpful in predicting future style changes. Rozhdestvenky offers the following chain of reasoning: ecological and valeological interests are often in contradiction with the game interests; the contradiction may be resolved through study of style; even the most sophisticated mathematical models cannot predict future style changes; however, systematization of culture, its typological and comparative study may give us tools to see the laws of style shift. Destruction of culture is called barbarism and is denounced and deplored. Barbarism can be physical (when facts of culture are physically lost); more interesting are two other forms: usagerelated (when access to facts of culture becomes limited or hampered. It remains to be seen if expensive opera tickets can be classified as usage-related barbarism) and educational barbarism (when knowledge is not passed on, or education loses prestige, or schools are stagnated in their curriculum and methods). All three forms of barbarism will wreck a country’s culture. We can avoid committing educational barbarism if we preserve the old achievements in our subjects, timely include new achievements in the curriculum and if we learn to teach our old subjects through the prism of new stylistic interests, as long as we do not confuse diseases, like consumerism, and temporary fashions, like messy look in one’s hairstyle, with valid new directions of style. 7