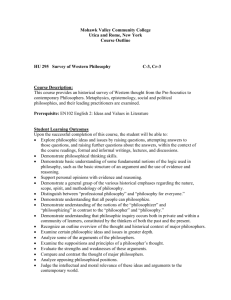

Finding Out What Dead Philosophers Mean

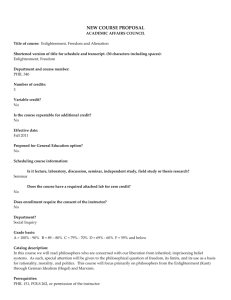

advertisement