Chapter 7: Power, Politics, and Leadership

advertisement

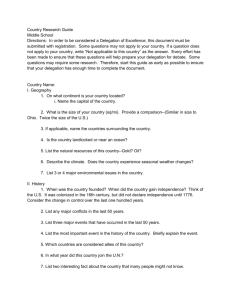

Chapter 7: Power, Politics, and Leadership KnowledgeBank #1, p. 203 Bases of Power and Transformational and Transactional Leadership One justification for studying bases of power is that they have direct application to understanding and applying leadership. Leanne E. Atwater and Francis J. Yammarino investigated how the bases of power, both personal and positional, relate to transformational and transactional leadership. [1] Consistent with the definition provided in Chapter 3, transformational leadership is depicted as the influence a leader acquires through being respected and admired by group members. In contrast, transactional leadership is largely based on exchanges between the leader and group members, such as using rewards and punishments to control behavior. Two hundred and eighty employees reporting to 118 supervisors in 45 organizations of many different types provided data for the study. Questionnaires were used to measure bases of power as well as perceptions of transformational and transactional leadership. (The Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire was used to measure the perceptions of leader behavior.) Of particular interest here, analysis of the data revealed that personal power, both referent and expert, was related to transformational leadership. Leaders who behave in a transformational manner (being charismatic, inspirational, intellectually stimulating, and considerate of individuals) are perceived to possess referent and expert power. Transformational leadership also showed a positive correlation with reward and legitimate power, yet was unrelated to coercive power. The message is that punitive bosses are rarely perceived as transformational. A less strong finding was that perceptions of power were not clearly linked to transactional leadership. An important implication of the study derived from regression analysis is that leaders who behave in a transformational manner are likely to be viewed as having a variety of positive bases of power. The data also suggest that transformational leaders are able to influence group members by virtue of the referent power attributed to them. Another implication justifies studying power in relation to leadership: The researchers conclude that power and leader behavior are interrelated. [1] Leanne E. Atwater and Francis J. Yammarino, “Bases of Power in Relation to Leader Behavior: A Field Investigation,” Journal of Business and Psychology, Fall 1996, pp. 3-22. Chapter 7: Power, Politics, and Leadership KnowledgeBank #2, p. 209 Guidelines for Effective Delegation In effective delegation, the leader assigns duties to the right people. The chances for successful delegation and empowerment improve when the tasks in question are assigned to capable, responsible, and self-motivated group members. Vital tasks should not be assigned to ineffective performers. Insight into the strengths and developmental needs of group members therefore enhances effective delegation. Also, when feasible, delegate the whole task. In the spirit of job enrichment, a manager should delegate an entire task to one group member rather than dividing it among several. Doing so gives the group member complete responsibility and enhances his or her motivation, and it also gives the manager more control over results. The leader should give as much instruction as needed, depending upon the characteristics of the group member. Some people will require highly detailed instructions, whereas others can operate effectively with general instructions. As explained in relation to empowerment, the most professionally rewarding type of delegation allows the group member to choose the method for accomplishing the assignment. As a leader or manager, retain some important tasks for yourself. In general, the manager should handle some high-output or sensitive tasks and any tasks that involve the survival of the unit. However, which tasks the manager should retain always depends on the circumstances. A basic management principle is to obtain feedback on the delegated task. A responsible manager does not delegate a complex assignment to a group member, then wait until the assignment is completed before discussing it again. Managers must establish checkpoints and milestones to obtain feedback on progress. A morale-building suggestion is to delegate both pleasant and unpleasant tasks to group members. When group members are assigned a mixture of pleasant and unpleasant responsibilities, they are more likely to believe they are being treated fairly. Few group members expect the manager to handle all the undesirable jobs. A related approach is to rotate undesirable tasks among group members. One or two group members should not be “empowered” to handle all the nasty assignments. A fundamental part of effective delegation is to step back from the details. Many managers are poor delegators because they get too involved with technical details. If a manager cannot let go of details, he or she will never be effective at delegation or empowerment. Finally, as in virtually all leadership endeavors, it is important to evaluate and reward performance. After the task is completed, the manager should evaluate the outcome. Favorable outcomes should be rewarded, and unfavorable outcomes may either be not rewarded or punished. It is important, however, not to discourage risk taking and initiative by punishing for all mistakes. [1] Delegation contributes to the practice of leadership because it is an excellent opportunity to coach the person accepting the delegated tasks. The assignment should be challenging enough to stretch the group member to acquire new skills. In the process of skill development, the group member might also benefit from a few constructive suggestions. Keith McCluskey is the president of a Chevrolet and Auto Nation USA franchise in Cincinnati, Ohio. His company won an award for being the number 1 seller in the world of medium-duty trucks. He offers the following comments about delegation, which support many of the points made here about empowerment and delegation: I assign a task or mission to a manager, explain briefly its importance and how it fits into a master plan at the dealership. We set a deadline for completion. It frees my time up to do something more important. When you move the project along to somebody else, his or her confidence grows, and there is a good chance that he or she will do it at least as well and probably better than I would have completed the task. If you move enough of the tasks on, you can think about the vision of the company and growing the revenue. [2] A rule of thumb for delegating effectively is the 80-20 rule, according Charles Lobitz, an executive who works with executives. “If they can do the job at 80% of what you can, you’ve freed up your time. The key is to stop believing it has to be done as well. Being perfect isn’t being successful.”[3] The reader is cautioned that some tasks do have to be performed perfectly such as calculating taxes owed, earnings per share, and producing pacemakers. [1] Several of the ideas in this section are based on David A. Whetton and Kim S. Cameron, Developing Management Skills, 5th ed. (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 2002), pp. 431425; Odette Pollar, “Delegation of Duties is the Key to Growth in the Workplace,” The Pryor Report, July 1998, p. 10; “Tom Sawyer at Work: The Art of Delegation,” www.employer-employee.com; Sharon Gadza, “The Art of Delegating,” HR Magazine, January 2002, pp. 75-77. [2] Quoted in John Eckberg, “Learning How to Delegate,” Gannett News Service, January 11, 1999. [3] Kayleen Schaefer, “Helping Manager Delegate Tasks Starts with Becoming Generalist,” The Wall Street Journal, June 26, 2006, B11.