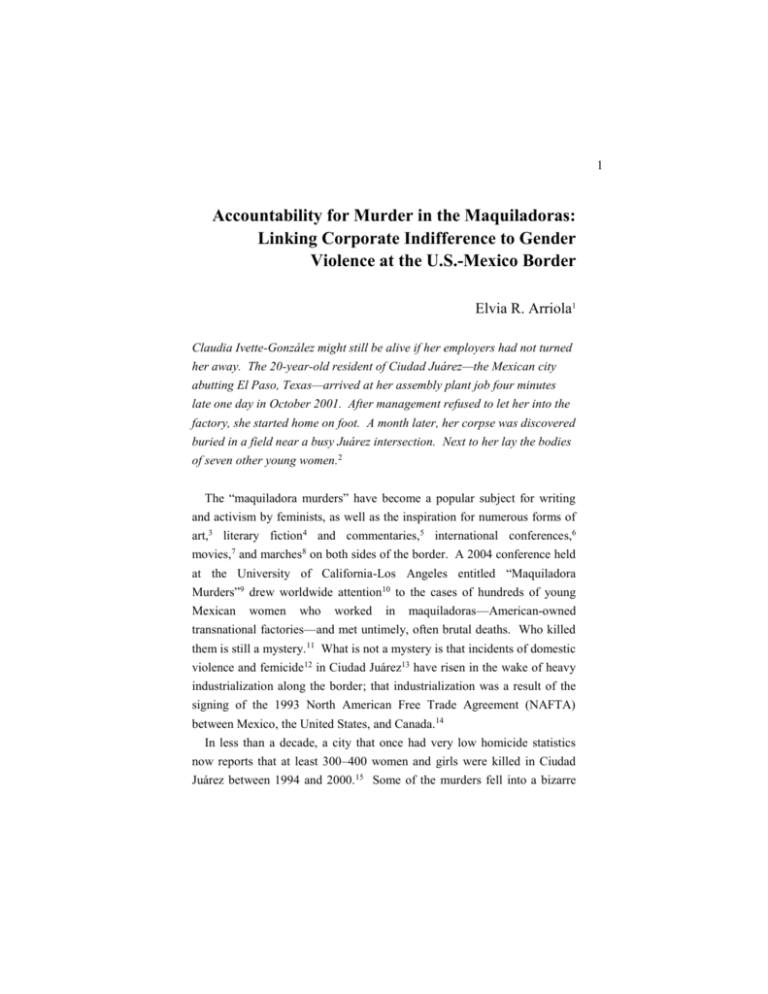

ACCOUNTABILITY FOR MUDER MURDER IN THE MAQUILADORAS:

advertisement