Sarah Ann Wells - William Faulkner Society

advertisement

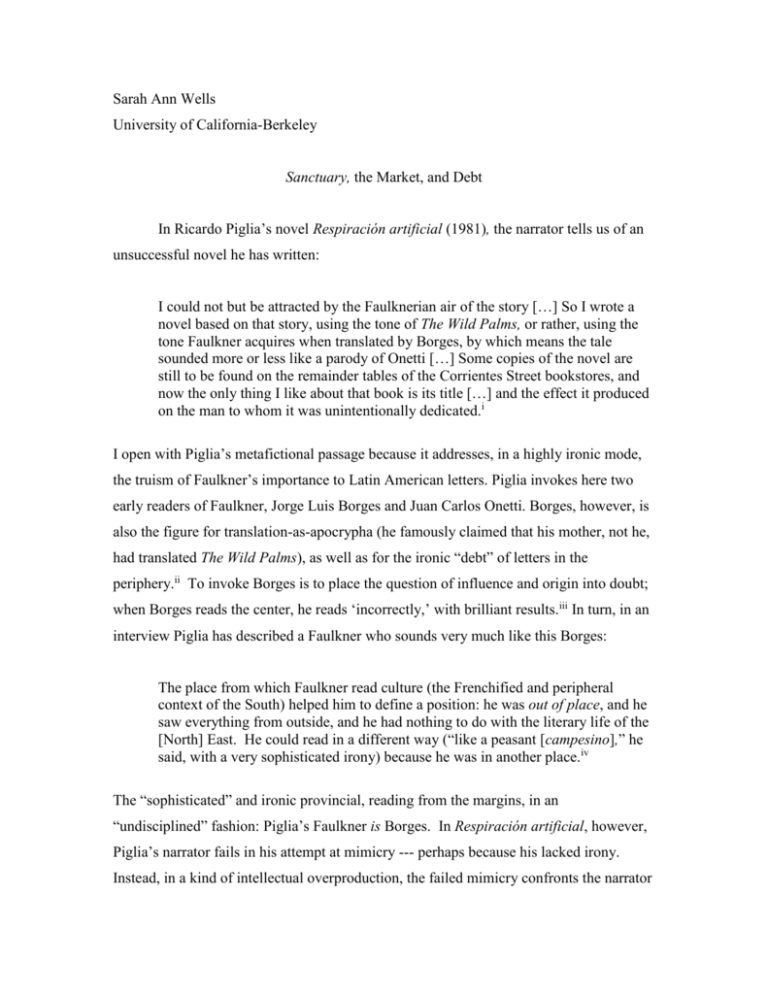

Sarah Ann Wells University of California-Berkeley Sanctuary, the Market, and Debt In Ricardo Piglia’s novel Respiración artificial (1981), the narrator tells us of an unsuccessful novel he has written: I could not but be attracted by the Faulknerian air of the story […] So I wrote a novel based on that story, using the tone of The Wild Palms, or rather, using the tone Faulkner acquires when translated by Borges, by which means the tale sounded more or less like a parody of Onetti […] Some copies of the novel are still to be found on the remainder tables of the Corrientes Street bookstores, and now the only thing I like about that book is its title […] and the effect it produced on the man to whom it was unintentionally dedicated.i I open with Piglia’s metafictional passage because it addresses, in a highly ironic mode, the truism of Faulkner’s importance to Latin American letters. Piglia invokes here two early readers of Faulkner, Jorge Luis Borges and Juan Carlos Onetti. Borges, however, is also the figure for translation-as-apocrypha (he famously claimed that his mother, not he, had translated The Wild Palms), as well as for the ironic “debt” of letters in the periphery.ii To invoke Borges is to place the question of influence and origin into doubt; when Borges reads the center, he reads ‘incorrectly,’ with brilliant results.iii In turn, in an interview Piglia has described a Faulkner who sounds very much like this Borges: The place from which Faulkner read culture (the Frenchified and peripheral context of the South) helped him to define a position: he was out of place, and he saw everything from outside, and he had nothing to do with the literary life of the [North] East. He could read in a different way (“like a peasant [campesino],” he said, with a very sophisticated irony) because he was in another place.iv The “sophisticated” and ironic provincial, reading from the margins, in an “undisciplined” fashion: Piglia’s Faulkner is Borges. In Respiración artificial, however, Piglia’s narrator fails in his attempt at mimicry --- perhaps because his lacked irony. Instead, in a kind of intellectual overproduction, the failed mimicry confronts the narrator at the remainder tables on Corrientes, where (presumably) bad copies of Faulkner go to die. These two excerpts from Piglia underscore the relationship between author, market, and reading public, through a strategic irony of the periphery, one that I wish to keep in mind. While Faulkner had been taken up by Latin America writers as early as the 1930s, the importance of Faulkner was not consolidated until the Boom in Latin American letters of the 1960s and 1970s, and the subsequent ‘Boom’ in scholarly production, especially in the U.S., which emphasized The Sound and the Fury, Absalom, Absalom!, As I Lay Dying, and the short story “A Rose for Emily.”v The emphasis on the Boom writers --- including Carlos Fuentes, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and Mario Vargas Llosa --is understandable, given that these self-consciously crafted themselves as disciples of Faulkner. Their lengthy, universalizing novels, for example, clearly express the kind of world-making strategies Faulkner developed with Yoknapatawpha.vi This is the group of writers that Jean Franco has deemed “the generation of parricides” (225); the killers of the past-father (including Iberian letters and the regional novel) in order to inaugurate a new literature. For this foundational gesture to succeed, as both Angel Rama and Idelber Avelar have explored, discourses surrounding the boom have effaced its literary predecessors, by declaring Latin American letters until their arrival a “barren” zone, “undeveloped.” My project invites a move away from taking at face value the words of Fuentes and others when they write about the importance of Faulkner, and implicitly of themselves, as writers somehow free from the imperatives of literature in a “backwards” region. For modernism in Latin America did not begin with the Boom ---- unless we hold to a very narrow definition of modernism. In fact, the anxiety of the autonomous artist and the relationship between this anxiety and an imperative to stretch and twist traditional forms of representation, an anxiety that plagued earlier writers such as Ruben Dario and Jose Marti, Borges and Faulkner, is at the center of modernist production, and it occupies the center in a particular way for writers who come from “off” economies, those peripheral regions and nations where modernization and modernity can only be spoken about in the plural. In such a context, Lino Novás Calvo, a Cuban novelist and journalist, rendered Sanctuary into Spanish only three years after its 1931 appearance in the United States. Virtually nothing has been written about this first “contact,” probably because of the current noncanonical status of both Novás Calvo and of Sanctuary itself.vii Taking this translation as a kind of encounter, I propose that Sanctuary self-consciously highlights the anxious relationship between literature and the market, a particularly acute problem for writers in economies for which the professionalization of the writer has been problematic. I argue that this is a problem of form, not just of themes (if it is even possible to separate the two); Sanctuary is not just “about” illicit economies and monstrous modernities, it also invokes these problems within its very structures. There is much to be said about the way the novel des this, but I will focus here on perhaps the most notorious of Faulkner’s paratexts, the Preface to the 1932 edition. Santuario was published in 1934 by the editorial Espasa-Calpe, as part of a collection entitled “Hechos sociales,” comprised of left-leaning, social realist, nonliterary works. While this might seem an odd place to locate Faulkner, it is worth noting that The Hamlet, too, was published in Buenos Aires by a Marxist publisher. In his Prologue to the translation of Sanctuary, Antonio Marichalar tries to justify Faulkner’s novel as a kind of “distorted” social realism, or documentary: not a mirror, he states, but a “deformed vision,” “an oblique reality,” “stained/dyed with irony.” The gap between this reading and the hegemonic one that circulated in the U.S. is impressive. In Creating Faulkner’s Reputation, Lawrence Schwartz shows a tendency within U.S. literary criticism to read Faulkner as dramatically opposed to the “social fictions” of the 1930s. According to this interpretation, Faulkner was all dark and unredeemed perversion to the ‘responsible’ fictions of, say, Steinbeck. Yet these early readers of Faulkner in Latin America suggest a different concern, which we could call a productively “off” reading of Faulkner. In this reading, Faulkner’s fiction calls for an examination of the strange modes opened up in spaces of uneven modernity.viii Published in the Modern Library’s 1932 edition of Sanctuary, the Preface establishes a persona that suggests the novel’s continual reworking and simultaneous critique of the tropes and forms of popular culture, above all pulp literature. Several critics have taken Faulkner at his word when he insists in the Preface that Sanctuary was—and can only be----a “cheap idea.” David Minter, for example, uses the Preface as a biographical font, but it seems more convincing to read it as a paratext that self-fashions a particular role for the author, one that is created vis-à-vis his relationship to the novel itself.ix We might say, in this respect, that Faulkner is very Borges; his paratexts often ironically stage an author-figure who is not equivalent to the author-subject. I would argue that Faulkner invokes the “cheap idea,” the pulp genre that houses it, and the cultural circuits that produce it, in order to implicate himself and the reader in the fraught economies the novel both describes and enters into.x Constructing himself as a laborer, Faulkner links his literary production to the monotonous repetition of coal-shoveling. Although he is ostensibly describing the creation of As I Lay Dying---the novel, along with The Sound and the Fury, that is allotted the “disinterested” position in contrast to the market-driven inception of Sanctuary---these descriptions frame Sanctuary and not the earlier novel. The intervals of coal-shoveling and type-writing become linked to the bang-‘em’-out production of the cheap idea. The “cheap” in the “cheap idea” refers simultaneously to two orders: the economic and the symbolic. As such, cheap functions paradoxically: to be cheap is to become rich, which is why the industry of the cinema, cited throughout the novel, is simultaneously cheap and rich.xi On one hand, cheap invokes Faulkner’s desire to make money: it culls images of the circulation of cheaply-printed texts that will hopefully (as he says in the last line of the Preface), line his pockets. Simultaneously, cheap functions as a self-criticism according to the logic of symbolic capital. In the Preface the short, repetitive sentences suggest something of the novel’s own formal qualities; as though the novel had inaugurated the author (rather than the other way around), the Faulkner who emerges is a series of synecdoches: the gut and the wallet. The “Good God, I cant publish this. We’d both be in jail,” ostensibly the publisher’s initial response to Sanctuary, conjures up immediately the novel’s own interest in underground economies. Inversely, the novel’s particular forms---its short chapters (and attention span), its long pauses and abrupt returns to various narrative threads, its strange bursts of comic relief in the form of stock, grotesque characters--evoke the stop-and-start of the night laborer. A narrative of drive and punishment inscribed in the Preface also yokes it to the novel. The ‘hard-gutted’ young Faulkner morphs into the “soft” one who is willing to sell to make money. He has “written [his] guts into The Sound and the Fury,” which is identified with the ‘fitness’ of an earlier period where he wrote without any thought of economic transactions. When the publisher initially refused the manuscript as too sensational, Faulkner presents himself as split.xii “So I told Faulkner, ‘You’re damned. You’ll have to work now and then for the rest of your life.’” The antagonism towards the market and the attraction to it is here ironically invoked: one Faulkner desires money, the other wants to distance himself. If we compare this personae to that of the Agrarian manifesto, I’ll Take My Stand, we see something of the bold contours of Faulkner’s claim. The South as spiritual vanguard, the South as a space of leisure in contrast to the hyper-capitalism of the North, reads as a fantasy in light of Faulkner’s laborer-writer, struggling to produce “the most horrific tale I could imagine,” “What a person in Mississippi would believe to be the current trends.” In the Preface Sanctuary is framed as something ephemeral, non-durable, unessential: “I think I had forgotten about Sanctuary, just as you might forget about anything made for an immediate purpose.” The “immediacy” constructing Sanctuary and its author-personae is central, because the rush and pull of the market and the traffic in illicit, nondurable ‘goods’ (alcohol and prostitution) is precisely what the novel grapples with. Contemporary anti-kitsch and high modernist arguments both in the Europe and in the U.S. feared this reproducibility, unrooted.xiii Such arguments failed to take into account, as Fredric Jameson will later, the mutually determining status of mass culture and modernism, something Faulkner is already hinting at. Thus, to be too new, too novel, impermanent, all surface is a fear the novel points to both within and outside of its pages. While Faulkner foregrounds labor in the coal-shoveling allusions, he simultaneously stresses it in his narrative of the manuscript’s revision. “I had to pay for the privilege of rewriting it,” he writes ironically. In contrast to such assertions of Sanctuary’s rapid-fire temporality, however, Noel Polk has noted that the manuscript is one of the most intensely edited of any of Faulkner’s works (294).xiv The revised version is “economic and precise” (Polk 301-2; 304); Faulkner’s revision heightens, rather than diminishes, the novel’s explicit relationship to the market, to consumption. Yet, while in much of the novel, as in the Preface, short, cropped sentences reel off information, the reader also must encounter traces of the original manuscript in the explicitly modernist voice of Horace.xv As a consequence of their scarcity, these kinds of passages jut out more, lending the text its peculiar, uneven texture. This texture, I would argue, is a staging of the problems of modernities in the multiple. Writing for the market, a remainder (Horace) persists, but it is Horace who seems ‘out of place,’ and Sanctuary’s Preface hints at why. The Preface registers an important anxiety: to write for the market is very different than to merely be a successful writer.xvi The text is a tactile object that circulates in spaces that both determine it and are determined by it, which is another way of saying that the ephemerality of literature written for the market makes it historical in spite of itself, never ‘timeless.’xvii In this sense, the Preface anticipates (after the fact) the formal qualities of novel itself: through the use of chapter breaks to simultaneously accumulate and frustrate the reader, its repetitive citation and saturation of clichés of the underworld, its self-conscious borrowing from the texts of popular culture in order to exhaust them.xviii In so doing, it is able to carve out a narrow space for itself that is neither isolated from nor respectful of the market: it would seem to acknowledge the market as a structuring and constitutive power but not as a limiting principle. Self-consciously, it takes what it has been handed in the ways of tools in order to show their power but their ultimately threadbare premises.xix In her provocative article on Go Down, Moses Susan Willis has argued that Faulkner’s ‘other’ “can only be the financial and industrial interests located in the Northern metropolis” (85), noting that the kinds of transitions Faulkner grappled with in his novels suggested an attention to what was taking place in the South during the time of their inception and publication: the shift from periphery to semi-periphery, from producer of primary products to producer of labor for the industrialized North (94-5). In this sense, we could argue that the setting of Sanctuary converges with the context of its production: it is, from with in and without, a struggle of how to articulate these changes in literary language.xx In the 1930s, Latin American intellectuals were also prompting a shift in the way in which dependency was thought in their regions. This process was articulated through different modes in different national and regional contexts, a difference that I have not had sufficiently explored here; Novas Calvo’s Cuba, for example, a near-colony of the U.S.; Borges’ Argentina, a competitor in the exporting of primary products. Nevertheless, we might say that within Latin American intellectual production the issue was not the transition from periphery to semi-periphery, but rather the emergence of a discourse of “debt” or “lack” presupposed in the deviation from the center.xxi This stance dovetailed, not coincidentally, with the pre-history of programs such as import substitution, emphasizing the degree to which Latin America had been the producer of primary products for the first world. It is at this point that Borges wrote his first reviews of Faulkner’s novels, recognizing the Southern author as a fellow “criollo”; at this point Novás Calvo renders Faulkner’s defamiliarizing prose to an even more “off” Spanish; at this point novelists, including the Argentine Roberto Arlt and the Brazilian Graciliano Ramos are writing modernist novels where the “Third World” author encounters the “devaluation” of his own prose within the peripheral economies --- without having read Faulkner. Perhaps it is here, then, where the field of Faulkner in Latin America can find a new point of entry, one where influence matters principally in its ironic form, and where authors negotiate with changing reading publics and markets before the possibility, or impossibility, of literature becoming, as in Piglia’s novel, a “remainder.” Bibliography Avelar, Idelber. “Oedipus in Post-auratic Times: Modernization and Mourning in the Spanish American Boom.” The Untimely Present: Postdictatorial Latin American Fiction and the Task of Mourning. Duke University Press: Durham, 1999. 22-38. Bauer, Arnold J. Goods, Power, History: Latin America’s Material Culture. Cambridge University Press: New York, 2001. Bloom, Clive. Cult Fiction: Popular Reading and Pulp Theory. St. Martin’s Press: New York, 1996. Cándido, Antonio. “Literature and Underdevelopment.” The Latin American Cultural Studies Reader. Duke University Press: Durham, 2004. 35-57. Chapman, Arnold. The Spanish American Reception of United States Fiction 1920-1940. University of California Press: Berkeley, 1966. Cohn, Deborah. “’He was one of us’: The Reception of William Faulkner and the U.S. South by Latin American Authors.” Comparative Literature Studies, Vol. 34, No. 2, 1997. 149-169. Delaney, Paul. Literature, Money and the Market. Palgrave: New York 2002. Eagleton, Terry. “Capitalism, modernism and postmodernism.” In Modern Criticism and Theory: A Reader. Ed. David Lodge. Harlow, U.K.” 2000. Faulkner, William. Sanctuary. Vintage: New York 1958. ---------Sanctuary: The Original Text. Ed. Noel Polk. Random House: New York, 1981. Fayen, Tanya. In Search of the Latin American Faulkner. University Press of America: Lanham, 1995. Franco, Jean. The Modern Culture of Latin America: Society and the Artist. Pall Mall Press: London, 1967. Gutiérrez, Miguel. Faulkner en la novela latinoamericana. Editorial San Marcos: Lima, 1999. Howe, Irving. William Faulkner: A Critical Study. 3rd edition, University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1975. Irby, James East. “La influencia de William Faulkner en cuatro narradores hispano americanos.” Dissertation, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico: Mexico, D.F., 1956. Jameson, Fredric. “Reification and Utopia in Mass Culture.” Social Text 1 (1979). 130148. Langford, Gerald. Faulkner’s Revision of Sanctuary: A Collation of the Unrevised Galleys and the Published Book. University of Texas Press: Austin, 1972. McCracken, Scott. Pulp: Reading Popular Fiction. Manchester University Press: Manchester, 1988. Minter, David. William Faulkner: His Life and His Work. Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, 1997. Nolan, William F. The Black Mask Boys: Masters in the Hard-Boiled School of Detective Fiction. William Morrow and Co.: New York, 1985. O’Brien, Geoffrey. Hardboiled America: Lurid Paperbacks and the Masters of Noir. Da Capo Press: New York, 1997. Parker, Robert Dale. “Sanctuary and Bad Taste.” Études Faulknériennes I. Sanctuary. Ed. Michel Gresset. Press Universitaries de Rennes, 1996. Piglia, Ricardo. “Sobre Faulkner.” Crítica y ficción. Editorial Planeta: Buenos Aires, 2000. 133-142. -------Artificial Respiration. Trans. Daniel Balderston. Duke University Press: Durham, 1994. Rama, Angel. “El ‘Boom’ en perspectiva.” Más allá del boom. Literatura y mercado. Marcha Editores: México, 1981. 51-110. Schivelbusch, Wolfgang. The Culture of Defeat: On National Trauma, Mourning and Recovery. Metropolitan Books: New York, 2003. Schwartz, Lawrence. Creating Faulkner’s Reputation: the Politics of Modern Literary Criticism. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1988. Sundquist, Eric J. “Sanctuary: An American Gothic.” Faulkner: the House Divided. Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, 1985. 44-60. Willis, Susan. “Aesthetics of the Rural Slum: Contradictions and Dependency in ‘The Bear.’” Social Text 1 (1979). 82-103. Woodward, C. Vann. The Burden of Southern History. Vintage Books: New York, 1960. Cf. Daniel Balderston’s translation, 13-14. Cf Beatriz Sarlo, Borges: A Writer on the Edge. iii Argentine Domingo F. Sarmiento’s misquoting of Fortoul in Facundo (as famously analyzed by Piglia in his 1980 article in the journal Punto de vista), Brazilian Oswald de Andrade’s modernist cannibal manifesto, and Puerto Rican Coco Fusco’s contemporary performance art come immediately to mind, but this stance has a history that dates back to the conquest, albeit with vastly different intonations and effects depending on artist, context, etc. iv “Sobre Faulkner,” 135 my emphasis. v See, for example, Mark Frisch, William Faulkner: su influencia en la literatura latinoamericana; also Deborah Cohn, “’He was one of us’: The Reception of William Faulkner and the U.S. South by Latin American Authors.” The first study on the importance of Faulkner in Latin America was James Irby’s 1956 dissertation, “La influencia de William Faulkner en cuatro narradores hispano americanos.” vi Several critics consider 1973, the year of Pinochet’s coup to overthrow the leadership of the democratically-elected socialist president, Salvador Allende, to constitute the end of the Boom. vii This was not always so, particularly in the case of Faulkner’s novel, which actually was quite successful in financial terms. Early paperback versions of his novels attempt to entice the reader with the phrase “By the author of Sanctuary”---a marketing strategy one would be hard-pressed to find today. “A reconstruction of accessibility would suggest that Sanctuary came to the attention of a Spanish publishing house due to the attention it received in U.S. critical reviews. The novel’s sensationalistic aspects, borrowed from popular literature, guaranteed its sales and name recognition for Faulkner. More importantly, its accessible sensationalism served to bring Faulkner’s technical innovations into the critics’ studies. It forced a retrospective analysis of the works that had preceded it: The Sound and the Fury and As I Lay Dying” (Fayen 86) viii . For example, Marichalar defends potential critiques of Novás Calvo’s translation of Sanctuary by stating that he “took care to conserve the ‘badly written’” aspects of the original text In a sense, Marichalar’s own awkward and interesting mixing of gothic imagery of shadows, the violence of hardboiled fiction, and the naturalist topos of the organic body going to pieces unintentionally reflects Faulkner’s own heady soup of genres/discourses, his novel’s uneven textures, as I explore below. ix CF, e.g., Minter 111. x “Sanctuary’s bad taste is calculated, a kind of aesthetic slumming...More broadly, Faulkner eagerly shares and helps produce his readers’ appetite for the pleasures of bad taste, for the arch good taste of calculated bad taste,” writes Robert Dale Parker (68) xi A similar tension embodies the world popular, as in popular fiction--Sanctuary being the novel that had made Faulkner the most revenue until the 1950 awarding of the Nobel Prize. In Pulp: Reading Popular Fiction, Scott McCracken notes the valence of the word, linked to texts (fiction and periodicals) beginning in the twentieth century: “Yet the term has always been contested, signifying on the one hand the authentic voice of the people and on the other their ignorance, vulgarity and susceptibility to manipulation. This conflict reflects not just two different versions of the same thing, but the fact that in the mass societies of modernity to be popular is also to be powerful and that power is fought for by political and economic interest groups. Popular fiction, like other forms of popular culture, is subject to that contest” (20). xii It is in the modernist period where the anxieties about art and the market come to be forcefully articulated by writers: “A cordon sanitarie around i ii serious fiction effectively turned an aesthetic question into a moral one: the question of the health of fiction” (Bloom 83). Citing Pound’s attempt “to establish a modernist myth of economic innocence” (154), Paul Delaney has examined now modernist culture fashioned an unlikely alliance with the market, despite its anxious attempts to separate itself from this sphere, through its dependence on the patronage of those who occupied what he calls rentier culture: “Exclusiveness does not conflict with commodification; it may even be the highest form of it” (149). xiii “Now, ‘now’ lasted forever and history was at an end,” says Clive Bloom in his analysis of pulp fiction, which came into its own at the same time (42). xiv In his revisions, Faulkner made the newer version less focused on Horace’s interiority, played up Popeye’s role, and ordered the narrative chronologically, omitting the original text’s anachronisms. According to Gerald Langford, Millgate was the first critic to suggest that the narrative created in the 1932 Preface to explain the origin and production of Sanctuary was not altogether accurate (5). Millgate noted that, while the Preface would lead us to believe that Faulkner had excised more sensationalistic, “cheap” moments, the galleys reveal that no such censuring occurred. xv For example, “It was as though femininity were a current running through a wire along which a certain number of identical bulbs were hung” (116). There are several other such modernist ruptures in the novel. xvi “Pulp is the child of capitalism and is tied to the appearance of the masses and the urban...it is the embodiment of capitalism aestheticized, consumerized and internalized” (Bloom 14, author’s emphasis). xvii O’Brien dates the beginning of the hardboiled genre to 1922, with the appearance of Hammett’s first story in Black Mask (62). In Faulkner’s time, pulp magazines were generally phased out to make way for pulp novels (Nolan 31). Black Mask was founded by H.L. Mencken as a money-making venture to bankroll his more serious modernist journal, The Smart Set (Nolan, 19-20). We recognize the novel not only because of its invocation of forms familiar to its social world (such as the Prohibition narrative), but also because of its prescience: it anticipates the pulp novel and noir. (Roman Polanski’s Chinatown, for example, evokes it in several ways.) xviii This constant raising of interest (narrative as well as visual) only to rechannel it to a much murkier space constitutes a pattern for the novel as a whole, reflected in its constant “paroxysms” of jerky bodies and alcoholic excess. xix This critique is what would distinguish Sanctuary from later, post-modern appeals to popular culture and the link between art and commodity in late capitalism (as explored by Jameson and Eagleton. Cf Fredric Jameson, “Reification and Utopia in Mass Culture,” Postmodernism: the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism; Terry Eagleton, “Capitalism, modernism, postmodernism.” Faulkner’s novel does not celebrate the surface as in Jameson’s definition of postmodern art, but rather, as I suggest, struggles with a self-conscious internalization of mass culture. xx And, in negotiating this terrain, Sanctuary, especially in its Preface --and as “The Bear” will later on --- repeatedly circles around money as an insufficient compensation that points out the peripheral status of its social world. Willis writes, “For the semiperiphery, real authority can never be achieved; it necessarily resides elsewhere. In its absence, money fills the gap” (97). xxi CF Antonio Candido’s classic essay, “Literature and Underdevelopment” (1969).