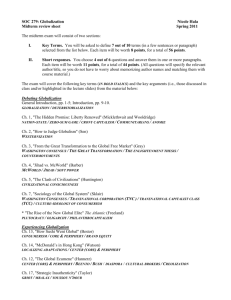

Ten Theses On Globalization

advertisement

Ten Theses On Globalization AMARTYA SEN, MASTER OF TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE, WAS AWARDED THE NOBEL PRIZE FOR ECONOMICS IN 1998. Over thousands of years, globalization has progressed through travel, trade, migration, spread of cultural influences and dissemination of knowledge and understanding. CAMBRIDGE—Doubts about the global economic order, which extend far beyond organized protests, have to be viewed in the light of the dual presence of abject misery and unprecedented prosperity in the world in which we live. Even though the world is incomparably richer than ever before, ours is also a world of extraordinary deprivation and of staggering inequality. We have to bear in mind this elemental contrast to interpret widespread skepticism about the global order, and even the patience of the general public with the socalled “anti-globalization” protests, despite the fact that they are often frantic and frenzied and sometimes violent. Debates about globalization demand a better understanding of the underlying issues, which tend to get submerged in the rhetoric of confrontation, on one side, and hasty rebuttals, on the other. Some general points would seem to need particular attention. 1. ANTI-GLOBALIZATION PROTESTS ARE NOT ABOUT GLOBALIZATION: The so-called “anti-globalization” protesters can hardly be, in general, anti-globalization, since these protests are among the most globalized events in the contemporary world. The protesters in Seattle, Melbourne, Prague, Quebec, Genoa and elsewhere are not just local kids, but men and women from across the world pouring into the location of the respective events to pursue global complaints. 2. GLOBALIZATION IS NOT NEW, NOR IS IT JUST WESTERNIZATION: Over thousands of years, globalization has progressed through travel, trade, migration, spread of cultural influences and dissemination of knowledge and understanding (including science and technology). The influences have gone in different directions. For example, toward the close of the millennium just ended, the direction of movement has been largely from the West to elsewhere, but at the beginning of the same millennium (around 1000 AD), Europe was absorbing Chinese science and technology and Indian and Arabic mathematics. There is a world heritage of interaction, and the contemporary trends fit into that history. 3. GLOBALIZATION IS NOT IN ITSELF A FOLLY: It has enriched the world scientifically and culturally and benefited many people economically as well. Pervasive poverty and “nasty, brutish and short” lives dominated the world not many centuries ago, with only a few pockets of rare affluence. In overcoming that penury, modern technology as well as economic interrelations have been influential. The predicament of the poor across the world cannot be reversed by withholding from them the great advantages of contemporary technology, the well-established efficiency of international trade and exchange and the social as well as economic merits of living in open, rather than closed, societies. What is needed is a fairer distribution of the fruits of globalization. 4. THE CENTRAL ISSUE, DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY IS INEQUALITY: The principal challenge relates in one way or another to inequality—between as well as within nations. The relevant inequalities include disparities in affluence, but also gross asymmetries in political, social and economic power. A crucial question concerns the sharing of the potential gains from globalization, between rich and poor countries, and between different groups within countries. 5. THE PRIMARY CONCERN IS THE LEVEL OF INEQUALITY, NOT ITS MARGINAL CHANGE: By claiming that the rich are getting richer and the poorer getting poorer, the critics of globalization have, often enough, chosen the wrong battleground. Even though many sections of the poor in the world economy have done badly (for a variety of reasons, involving domestic as well as international arrangements), it is hard to establish an overall and clear-cut trend. Much depends on the indicators chosen and the variables in terms of which inequality and poverty are judged. But this debate does not have to be settled as a precondition for getting on with the central issue. The basic concerns relate to the massive levels of inequality and poverty—not whether they are also increasing at the margin. Even if the patrons of the contemporary economic order were right in claiming that the poor in general had moved a little ahead (this is, in fact, by no means uniformly so), the compelling need to pay immediate and overwhelming attention to appalling poverty and staggering inequalities in the world would not disappear. 6. THE QUESTION IS NOT JUST WHETHER THERE EXISTS SOME GAIN FOR ALL PARTIES, BUT WHETHER THE DISTRIBUTION OF GAINS IS FAIR: When there are gains from cooperation, there can be many alternative arrangements that benefit each party compared with no cooperation. It is necessary, therefore, to ask whether the distribution of gains is fair or acceptable, and not just whether there exists some gain for all parties (which can be the case for a great many alternative arrangements). As J. F. Nash, the mathematician and game theorist, discussed more than half a century ago (in a paper called “The Bargaining Problem” published in Econmetrica in 1950, cited by the Royal Swedish Academy in awarding him the Nobel prize in economics), in the presence of gains from cooperation, the central issue is not whether a particular joint outcome is better for all than no cooperation (there are many such alternatives), but whether it yields a fair division of the benefits. To consider an analogy, to argue that a particularly unequal and sexist family arrangement is unfair, it does not have to be shown that women would have done comparatively better had there been no families at all, but only that the sharing of the benefits of the family system is seriously unequal and unfair as things are currently organized. 7. THE USE OF THE MARKET ECONOMY IS CONSISTENT WITH MANY DIFFERENT INSTITUTIONAL CONDITIONS, AND THEY CAN PRODUCT DIFFERENT OUTCOMES: The central question cannot be whether or not to make use of the market economy. It is not possible to have a prosperous economy without its extensive use. But that recognition does not end the discussion, only begins it. The market economy can generate many different results, depending on how physical resources are distributed, how human resources are developed, what “rules of game” prevail and so on, and in all these spheres, the state and the society have roles, within a country and in the world. The market is one institution among many. Aside from the need for pro-poor public policies within an economy (related to basic education and health care, employment generation, land reforms, credit facilities, legal protections, women’s empowerment and more), the distribution of the benefits of international interactions depends also on a variety of global arrangements (including trade agreements, patent laws, medical initiatives, educational exchange, facilities for technological dissemination, ecological and environmental policies and so on). 8. THE WORLD HAS CHANGED SINCE, THE BRETTON WOODS AGREEMENT: The international, economic, financial and political architecture of the world, which we have inherited from the past (including the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and other institutions), was largely set up in the 1940s, following the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944. The bulk of Asia and Africa was still under imperialist dominance then; tolerance of insecurity and poverty was much greater; the idea of human rights was still very weak; the power of NGOs (nongovernment organizations) had not emerged yet; the environment was not seen as particularly important; and democracy was definitely not seen as a global entitlement. 9. BOTH POLICY, AND INSTITUTIONAL CHANGES ARE NEEDED: The existing international institutions have, to varying extents, tried to respond to the changed situation. For example, the World Bank, under James Wolfensohn’s guidance, has revised its priorities. The United Nations, particularly under Kofi Annan’s leadership, has tried to play a bigger role, despite financial stringency. But more changes are needed. Indeed, the power structure underlying the institutional architecture itself needs to be reexamined in the light of the new political reality, of which the growth of globalized protest is only a loosely connected expression. The balance of power that reflected the status quo in the 1940s also has to be reexamined. Consider the problem of management of conflicts, local wars and the spending on armament. The governments of Third World countries bear much responsibility for the outrageous continuation of violence and waste, but also the arms trade is encouraged by world powers that are often the main sources of armament export. Indeed, as the Human development Report of the 1993 UN Development Program pointed out, not only were the top five arms-exporting countries precisely the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, but also they were, together, responsible for 86 percent of all the conventional weapons exported during the period studied. It is not hard to explain the inability of the world establishment to deal more effectively with these merchants of death. The anti-globalization protests are themselves part of the general process of globalization, from which there is no escape and no grate reason to seek escape. The recent difficulties even in getting support for a joint crackdown on illicit arms (as proposed by Kofi Annan) is a small illustration of a big obstacle related to the global power balance. 10. GLOBAL CONSTRUCTION IS THE NEEDED RESPONSE TO GLOBAL DOUBTS: The antiglobalization protests are themselves part of the general process of globalization, from which there is no escape and no great reason to seek escape. But while we have reason enough to support globalization in the best sense of the idea, there are also critically important institutional and policy issues that need to be addressed at the same time. It is not easy to disperse the doubts without seriously addressing the underlying concerns that motivate those doubts. That, at any rate, should not come as a surprise. More Progress in the Halls of Power Than Out CHRIS PATTEN, external affairs commissioner of the EU, was the last governor of Hong Kong. Nobody should fudge the difference between peaceful demonstration and violence. There is a huge gap between those that go to international conferences in Prague, Gothenberg and Genoa as members of non-governmental organizations with a legitimate concern about the environment or poverty and those with clubs and helmets who are determined to find an excuse to throw Molotov cocktails and smash in the windows at McDonalds. These violent demonstrators should be dealt with forcefully. Everyone regrets the death in Genoa. But if the demonstrations had been peaceful, that would not have happened. The problem with the dialogue with the peaceful demonstrators is that there isn’t one focus, but a disparate number of causes. And, in any event, anti-globalization is an absurd proposition. You cannot be for or against a process that is underway. You can have views about how to deal with the problems and promises it creates. There are ways to produce bigger and better opportunities for people to benefit from globalization. But, you can’t be against it. It is happening beyond the control of anyone and not at the instigation of any one country, like America. In order to deal with the problems and realize the promises, what is needed is international cooperation. What is needed is precisely the kind of organizations the demonstrators are campaigning against. At the European Council meeting in Gothenberg last spring, where alas demonstrators were also shot, we were debating “sustainable development.” Frankly, we were making more progress toward sustainable development in the hall than was being made by those outside. I’m all for having a dialogue. But it is quite difficult when some people don’t want to listen. What I am absolutely certain about is that those who are demonstrating in a well-meaning way against freer trade, for example, are in practice advocating policies that will make poor people poorer and further degrade the global environment. At the same time there are serious issues we need to address—like the billion people living on less that $1 a day; like the AIDS pandemic in Africa and parts of Asia; like malaria and TB; like the international drug trade. Finally, as these demonstrations are bound to continue, democratic societies will be forced to face the issue of legitimacy of these protest groups. What gives these self-appointed activists the right to try to shut down the meetings of democratically elected leaders? Who has chosen them to speak in their name? Don’t Trash McDonald’s JACK GREENBERG, the CEO of McDonald’s, was recently interviewed by Foreign Policy editor Moises Naim. His comments are excerpted from a longer conversation in the summer issue of Foreign Policy magazine. There is an assumption that we’re some big American company that exports things everywhere else to make a lot of money. Sure, we’re everywhere, but so is Nokia. So is NBC, so is CNN. (McDonald’s) is a global brand, but we run our business in a fundamentally different way that ought to appeal to some critics of globalization. We are a decentralized entrepreneurial network of locally owned stores that is very flexible and adapts very well to local conditions. We offer an opportunity to entrepreneurs to run a local business with local people supplied by a local infrastructure. Each creates a lot of small businesses around it. Second, the idea that we damage the environment. Not only is the charge (that we raise cattle on land slashed from rainforests) not true, but our environmental record is generally very good. We’ve never bought cattle that were anywhere near a rainforest. We’ve had the policy for 13 years. Third, this issue of McDonald’s as a cultural threat. We have become the symbol of everything people don’t like or are worried about in terms of their own culture. I think that charge reveals a level of general insecurity about identity rather than anything about McDonald’s, and it doesn’t square with the facts. You know, we’ve been in countries such as Japan, Canada and Germany for almost 30 years. I don’t see those cultures faltering because of McDonald’s. In fact, I think the opposite is true. Fourth, the idea that there’s a nutritional problem with McDonald’s. The facts are that we’re selling meat and potatoes and bread and milk and Coca-Cola and lettuce and everything else you can buy in a grocery store. What you choose to eat is a personal issue. Every nutritionist I’ve talked to says a balanced diet is the key to health. You can get a balanced diet at McDonald’s. It’s a question of how you use McDonald’s. Nobody’s mad at the grocery store because you can buy potato chips and pastries there. Nobody wants a full diet of that either. ● We are a lightning rod in France for a lot of criticism. But think about how consumers are behaving in France. What do the people do? Do they not vote with their feet by patronizing our stores? Are those restaurants not owned by French? Are they not buying French farmers’ products? Are they not creating jobs for the advertising agency, the construction company, the real estate agent, the lawyers, the accountants? Do they not create jobs for thousands of kids who, in France in particular, have had a hard time getting into the workforce? I mean, this is a fabulous story for France. It’s not being told. It is a wonderful story, not something we should be ashamed of or embarrassed about. It’s a great story. Most companies can’t tell this story, French or otherwise. ● Jose Bove (the French farmer who trashed a McDonald’s site) and a handful of terrorists are more interested in using McDonald’s as a convenient symbol than understanding the facts behind our business. (They should) recognize the essential local character of McDonald’s and find a more appropriate target for whatever it is that they’re angry about.