Senator Fall, President Wilson, and the Mexican Revolution

advertisement

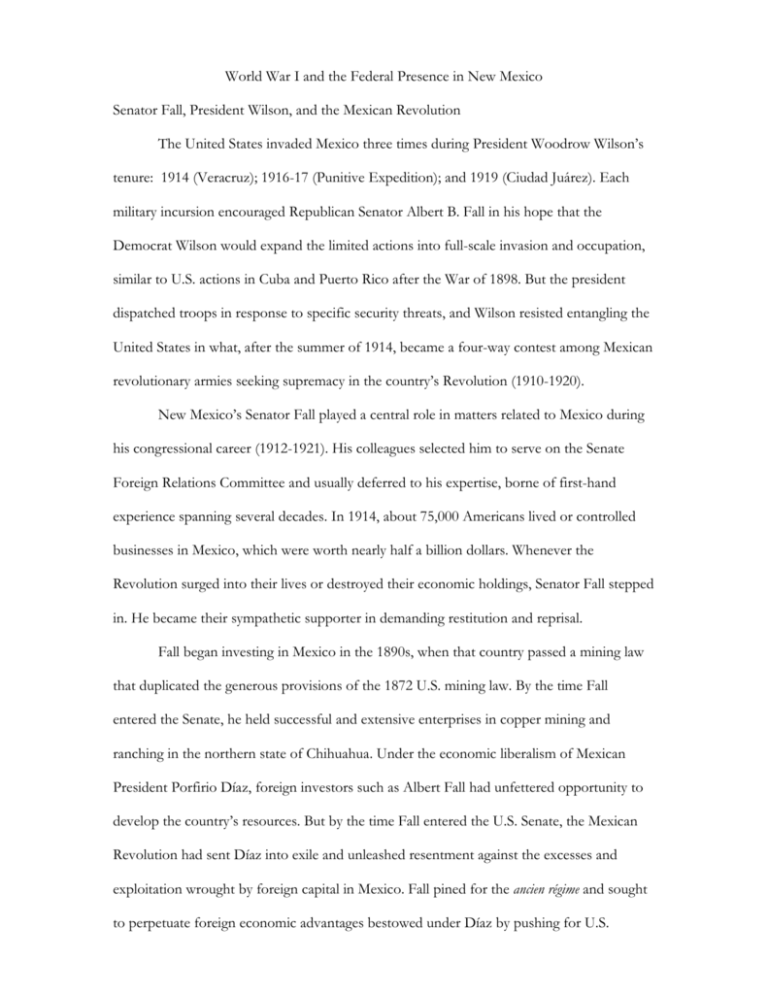

World War I and the Federal Presence in New Mexico Senator Fall, President Wilson, and the Mexican Revolution The United States invaded Mexico three times during President Woodrow Wilson’s tenure: 1914 (Veracruz); 1916-17 (Punitive Expedition); and 1919 (Ciudad Juárez). Each military incursion encouraged Republican Senator Albert B. Fall in his hope that the Democrat Wilson would expand the limited actions into full-scale invasion and occupation, similar to U.S. actions in Cuba and Puerto Rico after the War of 1898. But the president dispatched troops in response to specific security threats, and Wilson resisted entangling the United States in what, after the summer of 1914, became a four-way contest among Mexican revolutionary armies seeking supremacy in the country’s Revolution (1910-1920). New Mexico’s Senator Fall played a central role in matters related to Mexico during his congressional career (1912-1921). His colleagues selected him to serve on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and usually deferred to his expertise, borne of first-hand experience spanning several decades. In 1914, about 75,000 Americans lived or controlled businesses in Mexico, which were worth nearly half a billion dollars. Whenever the Revolution surged into their lives or destroyed their economic holdings, Senator Fall stepped in. He became their sympathetic supporter in demanding restitution and reprisal. Fall began investing in Mexico in the 1890s, when that country passed a mining law that duplicated the generous provisions of the 1872 U.S. mining law. By the time Fall entered the Senate, he held successful and extensive enterprises in copper mining and ranching in the northern state of Chihuahua. Under the economic liberalism of Mexican President Porfirio Díaz, foreign investors such as Albert Fall had unfettered opportunity to develop the country’s resources. But by the time Fall entered the U.S. Senate, the Mexican Revolution had sent Díaz into exile and unleashed resentment against the excesses and exploitation wrought by foreign capital in Mexico. Fall pined for the ancien régime and sought to perpetuate foreign economic advantages bestowed under Díaz by pushing for U.S. military occupation when, as soon proved the case, no revolutionary leader would do his bidding. Fall became the unofficial representative of Americans in Mexico. In speeches and hearings before his Senate sub-committee on Mexico, he highlighted attacks upon Americans with the aim of pressuring the Wilson Administration to occupy the country as the only sure means of providing more protection. The titles of a few of his early speeches convey the zeal with which he pursued a campaign against Mexico: July 22, 1912 “Outrages Upon American Citizens” and on March 9, 1914 “Conditions in Mexico: Protection of Americans and American Policy.” Throughout 1913 and into 1914, Fall’s denunciations of Mexican President Victoriano Huerta resonated with many of the President’s key advisors. At least two of his cabinet members (secretary of agriculture and the postmaster general) also held large investments in Mexico. In addition, the president’s principal political advisor, Texan Colonel Edward M. House, personally recounted for the President the complaints voiced by business interests of Texans, himself included, over threats to their investments in Mexican oil, railroads, and banking. As one scholar noted, “The Wilson administration and Mexico were deeply intertwined because of the shared economic interests on the part of key figures in the cabinet, congressional leaders, presidential advisers, and Democratic party financiers.” The beginning of 1914 opened a pivotal year in Mexican-U.S. relations as America’s president sought to clamp down on the civil war and social upheaval unleashed by the Revolution. He withheld diplomatic recognition, but Mexico’s current president, General Victoriano Huerta, remained in office. President Wilson and his advisors believed Huerta threatened not only U.S. economic interests but undermined America’s security. Huerta had accepted large sums of money and substantial quantities of arms from Germany. Moreover, to Wilson, the consummate advocate of democratic principles, Huerta had come to power in a coup and had blood on his hands. Indeed, Huerta’s insurrection of February 1913 resulted in the murder of Francisco Madero, who had been the first freely elected president of the country in many decades. It was Madera’s call for uprisings against the dictator Porfirio Díaz, beginning in November 1910, that forced Díaz into exile in late May 1911. By early 1914, when Wilson’s cabinet seriously addressed Mexico’s growing instability, four armies were arrayed against Huerta’s government—all with shifting alliances among themselves: Emilio Zapata in the south, Francisco Villa in the center-north, Álvaro Obregón in the western portion of the north, and Venustiano Carranza of the eastern part of the country’s northern region. Of these four, only Carranza enjoyed broad support among U.S. officials. The first step in a U.S.-engineered regime change occurred in late April 1914, when over 3,500 U.S. marines and sailors seized the Gulf port city of Veracruz to block delivery of German armaments intended for Huerta. Over 200 Mexicans died defending their city, and only the adroit diplomatic intervention of three Latin American countries averted outright war. In mid-November 1914, U.S. forces withdrew from Veracruz, their mission accomplished. Huerta fled the country in mid-July and Carranza soon became president. Unlike Madero, Huerta survived being deposed and went into exile in Spain. There, at about the same time U.S. troops left Veracruz, he began plotting a massive counterrevolution to restore him to power. Germany pledged active support in February 1915 and arranged financing in excess of $800,000. Germany did so primarily to tie up U.S. troops along the southern border with Mexico and secure a friendly country as a base of operations should the U.S. enter the war in Europe. Both schemes had a major impact on New Mexico. Newman, New Mexico, twenty miles northeast of El Paso: there on Sunday morning, June 27, 1915, U.S. officials took into custody former President of Mexico Victoriano Huerta and his foremost military commander, General Pascual Orozco. The two were about to return to Mexico and carry out major military plans: mobilize a new army, march on and capture Chihuahua City, and eventually push on to Mexico City and retake control of the government. The audacious scheme unraveled most unceremoniously. Federal investigators from the Department of Justice and the military tracked Huerta and Orozco as they converged in southern New Mexico and linked them to an illegal arms cache recently uncovered in El Paso. Initially detained at Newman, they soon were arranged and jailed in El Paso. There Orozco and Huerta chose different deaths. Orozco quickly broke out and two months later, on August 30, 1915, a posse that included a former marshal of Roswell ambushed and killed Orozco and his four companions in West Texas. Huerta seems to have given up on both his plans and himself and, aided by excessive alcohol, died in mid-January 1916. William Keleher of Albuquerque covered Huerta’s death watch as his last newspaper assignment. Years later, in surveying the larger drama glimpsed in Huerta’s death, Keleher wrote that the Mexican politician represented “one of President Woodrow Wilson’s more important casualties, a victim of Wilson’s calculated determination to smash Huerta’s political power in Mexico.” In early January 1916 Senator Fall secured approval of a Senate Resolution calling on the president and his new Secretary of State, Robert Lansing, to justify continued military inaction against Mexico. In mid-February Lansing rebuffed Fall’s call for armed invasion, but less than four weeks later an ill-conceived raid by revolutionary commander Francisco “Pancho” Villa against Columbus, New Mexico, forced the president to dispatch troops in a ten-month incursion known as the Pershing Punitive Expedition (the subject of a later entry). A final and poignant encounter on December 5, 1919 brought together Woodrow Wilson, Albert Fall, and Mexico’s revolution. On that afternoon, a constitutional crisis and international diplomatic impasse quickly ended at a meeting between Wilson and Fall in the president’s dimly light bedroom. Two months earlier, President Wilson had suffered a debilitating stroke, and Senator Fall, joined by a Democratic colleague, Gilbert Hitchcock of Nebraska, met him in his bedroom to address two issues: the response to a diplomatic stand- off with Mexico over the illegal arrest of an American consular agent in the city of Puebla and, for the Senate, an effort to assess whether the president was mentally competent to fulfill his duties. A carefully briefed and prepped President Wilson acquitted himself ably. The senators found him cheerful, alert, and “in mental and physical trim to meet emergencies as they arose.” Moreover, during the meeting word arrived that Mexican President Carranza had released the consular officer. By the time the senators departed the White House late that fall afternoon, both America and Mexico had taken a large step back from the brinkmanship that had marked their affairs for the previous decade. They also made a first small step forward in normalizing diplomatic and bilateral relations, a move that grew gradually during the 1920s and more vigorously in the 1930s. Senator Fall’s nearly eight-year campaign to impose reprisal and reparations upon Mexico diminished markedly in influence during 1920 and thereafter. His 3,551 page report wrapping up hearings held between September 8, 1919 and May 20, 1920 to “demonstrate the alleged perfidy and iniquity of the Carranza government in its dealings with the United States and its citizens” met with indifference on the part of the Wilson administration. © 2008 by David V. Holtby Albert B. Fall (on far right) and two unidentified men at a mining site, photograph, Albert Bacon Fall Collection (PICT 000-131-0002), Center for Southwest Research, University Libraries, The University of New Mexico. President Diaz in the Executive Chair. Godoy, Jose F. Porfirio Diaz, President of Mexico: The Master Builder of a Great Commonwealth. (New York and London, G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1910) p. 68. A U.S. official included this tribute to President Diaz in a laudatory biography published in 1910. His praise for the dictator resonated with U.S. government and business elites but not with the majority of Mexicans. Their discontent fueled a decade of revolution. Godoy, Jose F. Porfirio Diaz, President of Mexico: The Master Builder of a Great Commonwealth. (New York and London, G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1910) pp 166-167. These three graphs tell the same story: Mexico welcomed foreign investment during President Diaz’s rule (1876-1910). During his reign, U.S. investors came to dominate three key sectors of the Mexican economy: mining, railroads, and banking. Godoy, Jose F. Porfirio Diaz, President of Mexico: The Master Builder of a Great Commonwealth. (New York and London, G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1910) p.128. The Mining Industry graph. Godoy, Jose F. Porfirio Diaz, President of Mexico: The Master Builder of a Great Commonwealth. (New York and London, G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1910) p. 200. The Production of Gold and Silver graph. Godoy, Jose F. Porfirio Diaz, President of Mexico: The Master Builder of a Great Commonwealth. (New York and London, G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1910) p. 116.