Chapter 14, International and Culturally Diverse Aspects of Leadership

advertisement

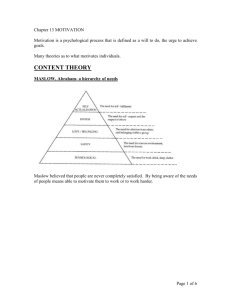

Chapter 14, International and Culturally Diverse Aspects of Leadership KnowledgeBank #1, p. 420 Applying a Motivational Theory Across Cultural Groups A practical way of understanding how cultural factors influence leadership is to illustrate how motivation theory might be applied to different cultural groups. Expectancy theory, which provides specific guidelines to leaders and managers, can be used to illustrate cross-cultural motivation. Doing so will illustrate the principle that some aspects of motivation theory apply across cultures, whereas other aspects must be modified. Two aspects of expectancy theory are especially important for understanding cross-cultural differences in motivation: perception of individual control over the environment, and appropriateness of rewards. Environmental Control. As analyzed by Nancy J. Adler, expectancy theories depend on the extent to which workers believe they have control over the outcome of their efforts, and how much faith they have in leaders to deliver rewards.[1] The assumption that workers believe they have control over their own fate may be culturally dependent. In countries where individualism dominates, employees may believe more strongly that they can influence performance and outcomes. In collectivist societies, such as Taiwan and Japan, the ties between the individual and the organization have a moral component. In the United States and similar cultures, many people believe that “where there is a will, there is a way.” Adler argues that the reasons that people in individualistic societies become committed to organizations are quite different from those of people in collectivist societies. An employee in an individualistic culture (such as the United States, Canada, or Germany) is more likely to ask, “What’s in it for me?” before responding to a motivational thrust. Employees with collectivistic values commit themselves to the organization more because of ties with managers and coworkers than because of intrinsic job factors or individual incentives. Despite the cultural generalization, the leader must be alert to individual and subcultural differences. Many Japanese workers are becoming less loyal to their employers and thus more self-centered and eager for individual recognition. Workers from rural areas in the United States are much more collectivist than their counterparts from large cities. One of the many reasons Saturn Motors located its plant in Tennessee is the presence of a more harmonious and loyal work force. Appropriateness of Rewards. Expectancy theories are universal because the motivator must search for rewards that have valence for individual employees. Leaders themselves must analyze the type and level of rewards that have the highest valence for individuals. The appropriateness of rewards is most strongly tied to individual differences, yet cultural differences are also important. The challenge is to find which rewards are effective in the particular culture. A study was conducted in a cotton mill in the Russian Republic of the former Soviet Union. One aspect of the study offered intrinsic rewards in the form of American goods to ninety-nine weavers from different shifts. Praise and recognition were also used as rewards. Receiving the goods as well as recognition and praise were contingent upon increases in the amount of top-grade fabric they produced. The rewards resulted in increased production. Another motivational technique, employee participation, contributed to performance decline.[2] The study relates to valence because many people believe that participation in decision making is a reward for virtually all workers. But among these Russian weavers, participative management was perceived to have negative valence. Perhaps participating in decision making was too foreign to their work culture to be acceptable. Many American managers have mistakenly assumed that a reward with a high valence among American workers will also have a high valence among workers from other cultures. In one situation, raising the salary of a particular group of Mexican workers motivated them to work fewer rather than more hours. A spokesperson for the Mexican workers said, “We can now make enough money to live and enjoy life in less time than previously. Now, we do not have to work so many hours.”[3] [1] Our analysis of expectancy theory across cultures is based on Nancy J. Adler, International Dimensions of Organizational Behavior, 2nd ed. (Mason, Ohio: South-Western College Publishing, 1991), pp. 157-160. [2] Dianne H. B. Welsh, Fred Luthans, and Steven M. Somner, “Managing Russian Factory Workers: The Impact of U.S. –Based Behavioral and Participative Techniques,” Academy of Management Journal, February 1993, pp. 58-79. [3] Adler, International Dimensions of Organizational Behavior, p. 159. Chapter 14, International and Culturally Diverse Aspects of Leadership KnowledgeBank #2, p. 432 Leadership at Progress Energy Speaks Out on Diversity Progress Energy is a $9 billion diversified energy company, headquartered in Raleigh, North Carolina. Anne Huffman, vice president of human resources and a member of Progress Energy’s Corporate Diversity Council answered these questions (among others) about diversity. What has been the most satisfying result of your diversity program? All of our employees have received diversity training and participated in discussion groups in which we talk about diversity in all of its dimensions—age, gender, race, sexual orientation, disabilities, etc. Many participants weren’t even aware of their biases until we got into these discussions. Participants talk about their experiences, and they help each other learn about and respect people’s differences. How does Progress Energy measure its progress? Each year we conduct a survey asking employees to rate the company on such issues as whether they feel supervisors deal fairly with everyone and whether their contributions are valued regardless of their gender, race, or job level. Since 1999 the overall satisfaction score has risen from 70 to 77, out of a possible 100. When over three-quarters of your workforce is satisfied, you are doing well. What are your other diversity goals? One of them is to have closer involvement with the Hispanic population, which has grown tremendously in our service area. We want to be viewed as a great place for Hispanics to work, and we’ve held focus groups on how to do this. We’ve also asked our Hispanic employees to get more involved in the recruitment effort. And this year we’ve created a corporate diversity scorecard, in which we align our diversity efforts with our strategic plan, including leadership development, employee engagement and retention. SOURCE: “Special Advertising Section: Speaking Out on Diversity,” Business 2.0 November 2004, p. 10.