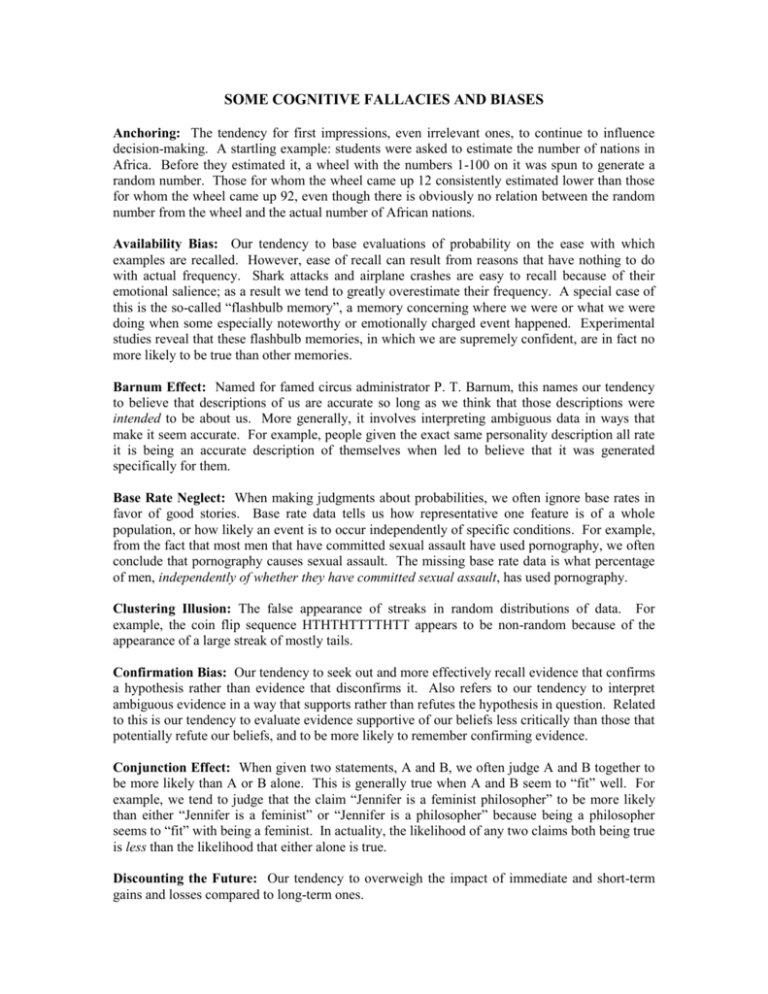

SOME COGNITIVE FALLACIES AND BIASES

advertisement

SOME COGNITIVE FALLACIES AND BIASES Anchoring: The tendency for first impressions, even irrelevant ones, to continue to influence decision-making. A startling example: students were asked to estimate the number of nations in Africa. Before they estimated it, a wheel with the numbers 1-100 on it was spun to generate a random number. Those for whom the wheel came up 12 consistently estimated lower than those for whom the wheel came up 92, even though there is obviously no relation between the random number from the wheel and the actual number of African nations. Availability Bias: Our tendency to base evaluations of probability on the ease with which examples are recalled. However, ease of recall can result from reasons that have nothing to do with actual frequency. Shark attacks and airplane crashes are easy to recall because of their emotional salience; as a result we tend to greatly overestimate their frequency. A special case of this is the so-called “flashbulb memory”, a memory concerning where we were or what we were doing when some especially noteworthy or emotionally charged event happened. Experimental studies reveal that these flashbulb memories, in which we are supremely confident, are in fact no more likely to be true than other memories. Barnum Effect: Named for famed circus administrator P. T. Barnum, this names our tendency to believe that descriptions of us are accurate so long as we think that those descriptions were intended to be about us. More generally, it involves interpreting ambiguous data in ways that make it seem accurate. For example, people given the exact same personality description all rate it is being an accurate description of themselves when led to believe that it was generated specifically for them. Base Rate Neglect: When making judgments about probabilities, we often ignore base rates in favor of good stories. Base rate data tells us how representative one feature is of a whole population, or how likely an event is to occur independently of specific conditions. For example, from the fact that most men that have committed sexual assault have used pornography, we often conclude that pornography causes sexual assault. The missing base rate data is what percentage of men, independently of whether they have committed sexual assault, has used pornography. Clustering Illusion: The false appearance of streaks in random distributions of data. For example, the coin flip sequence HTHTHTTTTHTT appears to be non-random because of the appearance of a large streak of mostly tails. Confirmation Bias: Our tendency to seek out and more effectively recall evidence that confirms a hypothesis rather than evidence that disconfirms it. Also refers to our tendency to interpret ambiguous evidence in a way that supports rather than refutes the hypothesis in question. Related to this is our tendency to evaluate evidence supportive of our beliefs less critically than those that potentially refute our beliefs, and to be more likely to remember confirming evidence. Conjunction Effect: When given two statements, A and B, we often judge A and B together to be more likely than A or B alone. This is generally true when A and B seem to “fit” well. For example, we tend to judge that the claim “Jennifer is a feminist philosopher” to be more likely than either “Jennifer is a feminist” or “Jennifer is a philosopher” because being a philosopher seems to “fit” with being a feminist. In actuality, the likelihood of any two claims both being true is less than the likelihood that either alone is true. Discounting the Future: Our tendency to overweigh the impact of immediate and short-term gains and losses compared to long-term ones. Endowment Effect: Our tendency to rate the value of something we already own above the value of something we do not possess. For example, we routinely set a price to sell something we own significantly higher than we indicate we would be willing to pay to attain that same object. False Consensus Effect: Our tendency to overestimate the degree to which others are similar to us in their beliefs, experiences, values or characteristics. Focused v. Unfocused Predictions: We tend to remember unfocused predictions (vagaries such as “you will meet a tall, dark stranger”) that are confirmed, and forget those that are disconfirmed. This is because only confirmation is memorable. (Thus, this is related to both the confirmation and availability biases.) We also tend to interpret ambiguous results in ways that confirm unfocused predictions. Framing Effect: The decisions we make often depend not on the information available to us, but rather on the way in which the decision is given to us. For example, people tend to reject medical procedures that have a 10% fatality rate, but accept medical procedures that have a 90% survival rate. 10% fatality just is 90% survival; the difference in acceptance is a result of the way in which the decision is presented to us, or framed. The context of the decision influences the decisions themselves. Fundamental Attribution Error: This is the attribution of situational behavior to character traits (typically made of others), such as judging that the person in line in front of us who is short with the cashier is just “a jerk”. Social psychology research has indicated that situational factors are far better predictors of behavior than character traits; yet we routinely explain behavior by appeal to such traits and ignore situational factors. Hindsight Bias: Using data currently at our disposal, we tend to greatly exaggerate the degree to which events that have already happened were predictable based on the evidence available at the time. In general, events that have actually happened are routinely judged to have been likely, and events that failed to occur to have been highly unlikely, regardless of their actual probability. Honoring Sunk Costs: We honor sunk costs any time we follow a course of action we no longer desire to follow or that is not working because we have already invested in it. As a result, we end up paying (with time, money or both) to do what we don’t want to do. In-Group Favoritism: Our tendency to empathize with (and hence consider the interests of) others based on the degree to which they are similar to us, and hence familiar. This is independent of considerations of bias in the pejorative sense. Lake Wobegon Effect: Named after the fictional town where “every child is above average”, this names our tendency to overrate our abilities compared to others. For example, most people rate themselves as above average in intelligence, leadership ability, studiousness, job performance, and driving ability; while almost no one rates themselves as below average in these things. Omission Bias: This is the intuitive assumption that doing harm is worse than failing to prevent harm. The problem is that this intuition takes no account of the degree of harm that actually occurs. Outcome Bias: Our tendency to judge behavior more positively or negatively based on what we know (or believe) about the outcome of that behavior. For example, many more people opposed the 2003 war in Iraq after the war began to stagnate than before, despite the fact that the same evidence was appealed to (misinformation about Iraq’s possession of WMDs, concerns about lacking an exit strategy, concerns about whether Iraq was connected to the 9/11 terrorist attacks, etc.). Related to Hindsight Bias. Outrage Heuristic: Our tendency to evaluate the moral status of actions or circumstances based not on actual considerations of harm, but on how angry it makes us or how offended by it we happen to be. Overclaiming: Our tendency to overestimate the value and impact of our own contribution due to our greater awareness of it. This can often lead us to self-serving and profoundly unjust accounts of what is fair and/or deserved. Overconfidence: Our tendency to overestimate the reliability and accuracy of our own beliefs. Representativeness Bias: We often estimate likelihoods and make judgments based on conformity to a stereotype. For example, we will tend to judge it to be far more likely for a woman to be a lawyer than a waitress if we know that she reads a lot and majored in philosophy. The problem is that any woman is more likely to be a waitress than a lawyer—our decision is the result of the fact that reading a lot and majoring in philosophy fit our stereotype of lawyers better than our stereotype of waitresses. There is experimental evidence that indicates that many of these stereotypes (or prototypes) are automatic; that is, they influence our decision without conscious awareness. Source Amnesia: Our tendency to recall information better than the source of the information. Status Quo Bias: Our tendency to overestimate the value or effectiveness of existing options, policies, etc.; including our tendency to both underemphasize both the losses that come from maintaining the status quo as well as the potential gains of change. This often persists even in the face of a clearly superior alternative. Subset Fallacy: Our tendency to reject policies that help some because one particular group is not benefited by it.