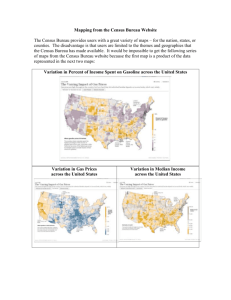

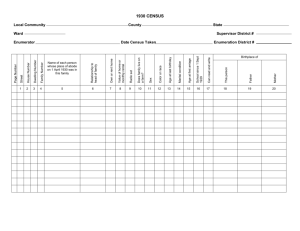

Census Confidentiality under the Second War Powers

advertisement