War in Iraq Propelling A Massive Migration

advertisement

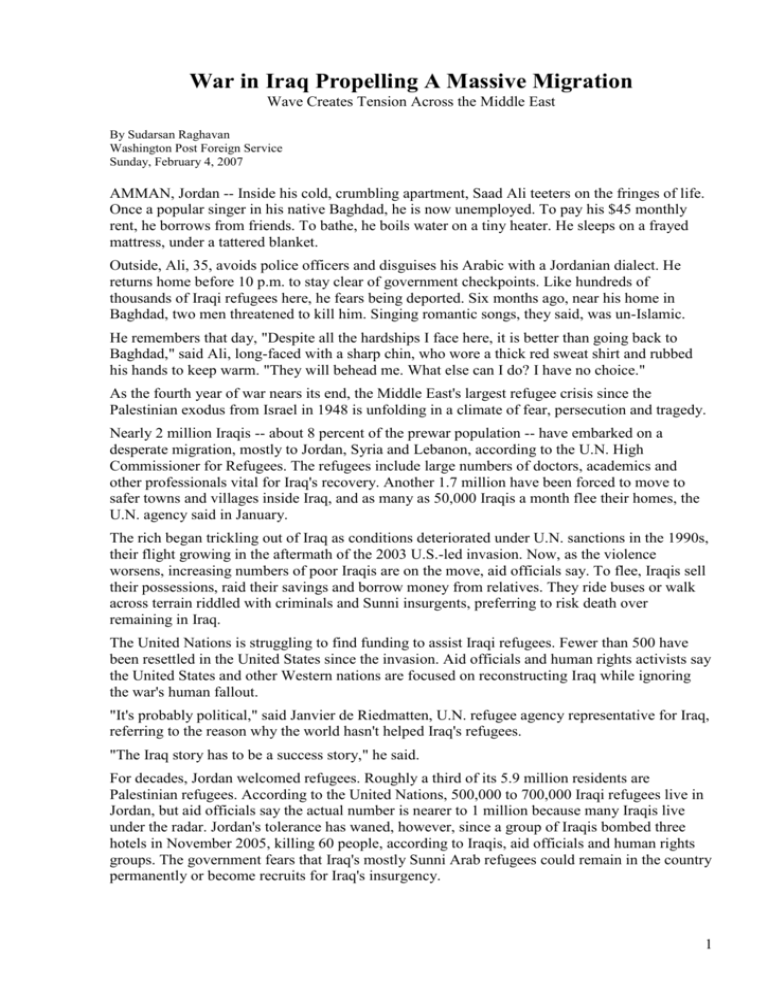

War in Iraq Propelling A Massive Migration Wave Creates Tension Across the Middle East By Sudarsan Raghavan Washington Post Foreign Service Sunday, February 4, 2007 AMMAN, Jordan -- Inside his cold, crumbling apartment, Saad Ali teeters on the fringes of life. Once a popular singer in his native Baghdad, he is now unemployed. To pay his $45 monthly rent, he borrows from friends. To bathe, he boils water on a tiny heater. He sleeps on a frayed mattress, under a tattered blanket. Outside, Ali, 35, avoids police officers and disguises his Arabic with a Jordanian dialect. He returns home before 10 p.m. to stay clear of government checkpoints. Like hundreds of thousands of Iraqi refugees here, he fears being deported. Six months ago, near his home in Baghdad, two men threatened to kill him. Singing romantic songs, they said, was un-Islamic. He remembers that day, "Despite all the hardships I face here, it is better than going back to Baghdad," said Ali, long-faced with a sharp chin, who wore a thick red sweat shirt and rubbed his hands to keep warm. "They will behead me. What else can I do? I have no choice." As the fourth year of war nears its end, the Middle East's largest refugee crisis since the Palestinian exodus from Israel in 1948 is unfolding in a climate of fear, persecution and tragedy. Nearly 2 million Iraqis -- about 8 percent of the prewar population -- have embarked on a desperate migration, mostly to Jordan, Syria and Lebanon, according to the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees. The refugees include large numbers of doctors, academics and other professionals vital for Iraq's recovery. Another 1.7 million have been forced to move to safer towns and villages inside Iraq, and as many as 50,000 Iraqis a month flee their homes, the U.N. agency said in January. The rich began trickling out of Iraq as conditions deteriorated under U.N. sanctions in the 1990s, their flight growing in the aftermath of the 2003 U.S.-led invasion. Now, as the violence worsens, increasing numbers of poor Iraqis are on the move, aid officials say. To flee, Iraqis sell their possessions, raid their savings and borrow money from relatives. They ride buses or walk across terrain riddled with criminals and Sunni insurgents, preferring to risk death over remaining in Iraq. The United Nations is struggling to find funding to assist Iraqi refugees. Fewer than 500 have been resettled in the United States since the invasion. Aid officials and human rights activists say the United States and other Western nations are focused on reconstructing Iraq while ignoring the war's human fallout. "It's probably political," said Janvier de Riedmatten, U.N. refugee agency representative for Iraq, referring to the reason why the world hasn't helped Iraq's refugees. "The Iraq story has to be a success story," he said. For decades, Jordan welcomed refugees. Roughly a third of its 5.9 million residents are Palestinian refugees. According to the United Nations, 500,000 to 700,000 Iraqi refugees live in Jordan, but aid officials say the actual number is nearer to 1 million because many Iraqis live under the radar. Jordan's tolerance has waned, however, since a group of Iraqis bombed three hotels in November 2005, killing 60 people, according to Iraqis, aid officials and human rights groups. The government fears that Iraq's mostly Sunni Arab refugees could remain in the country permanently or become recruits for Iraq's insurgency. 1 Now, the exodus is generating friction and anger across the region, while straining basic services in already poor countries. Iraqis are blamed for driving up prices and taking away scarce jobs. Iraq's neighbors worry the new refugees will carry in Iraq's sectarian strife. "The Jordan government does not want to encourage Iraqis to stay for a long time," said Gaby Daw, project officer for the Catholic charity Caritas Internationalis, one of the few aid agencies assisting Iraqi refugees. Into their new havens, Iraqis are bringing their culture and way of life, gradually reshaping the face of the Arab world. But the cost of escape is high. Feeding the bitterness of exile is a sense that outside forces created their plight. Many Iraqis here view the U.S.-led invasion that ousted President Saddam Hussein as the root of their woes. "We were promised a kind of heaven on earth," said Rabab Haider, who fled Baghdad last year. "But we've been given a real hell." Sad Goodbyes The road out of Iraq begins on Salhiye Street in Baghdad. On Jan. 13, knots of Iraqis waited to board 14 buses to Syria. Inside a travel agency, Raghed Moyed, 23, sat solemnly with her 12-year-old brother, Amar. It had become too dangerous for her to attend college, so she was heading to Damascus to continue her education. As she sat, her head bowed, she recalled the previous night, when she bade farewell to her friends. "It's really sad," said Moyed, her voice cracking as tears slid down her face. "I cried the whole way from the house to here. I don't want to leave Iraq, but it is hard to stay." Sameer Humfash, the travel agent, watched her cry. By his estimate, 50 to 60 families were fleeing each day on the buses lined up outside. Nowadays, Iraqis were heading mostly to Syria, he said. "They are not letting Iraqis in at the Jordanian border," interrupted Ahmed Khudair, one of Humfash's employees. Humfash makes all his passengers sign waiver forms that read: "I am traveling on my own responsibility and God is the only one that protects us." On the roads to both Jordan and Syria, Sunni insurgents have dragged Shiites from buses and executed them. Humfash stays in radio contact every hour with the bus driver, usually a Syrian. He always asks three questions, he said: "How is the road?" "Did they take any passengers?" "Did they hurt any passengers?" At the Border Along the Iraq-Jordan border Jan. 16, a brisk wind howled across the barren landscape. It was 1:45 p.m. Until recently, hundreds of cars and buses filled with Iraqis would have been lined up to enter Jordan. On this day, there were four vehicles. A Jordanian border security official said many Iraqis were afraid to travel through Anbar province, one of Iraq's most violent regions. Abu Hussam al-Khaisy, an Iraqi taxi driver, offered another explanation. The day before he had brought a family of seven Iraqis to the border, but Jordanian officials, he said, denied them admission with no explanation. "They are not giving permission to enter because they are scared about security," said Khaisy at a restaurant in Ruwayshid, a Jordanian rest stop about 55 miles from the border. In other 2 instances, he said, officials have turned away young Iraqi men who could take jobs away from Jordanians. Today, the government is making it increasingly difficult for Iraqis to reside legally in Jordan. It views Iraqis as temporary visitors, not refugees, and has not sought international assistance. Human rights activists and U.N. officials have accused Jordan of shutting its border to many Iraqis fleeing persecution and deporting others. Nasir Judah, a government spokesman, said Jordan has kept its door open to Iraqis even as they have become a burden on Jordan's economy and natural resources. In recent years, the influx was largely unregulated, but now tighter security measures are needed, he said. Iraqis, he added, have tried to enter Jordan using fake passports and identity cards. "There are no mass deportations of Iraqis," Judah said. "Otherwise the numbers would be dwindling, and they are not." On this day, Khaisy was driving Abu Wisam al-Azzawi, 35, back to Baqubah, a city about 35 miles northeast of Baghdad. Two months ago, members of Azzawi's immediate family were refused entry into Jordan, even though he owned a car dealership in Amman. Azzawi still remembers his son, on the Iraq side of the border, pleading through the cellphone: "Daddy, don't leave us." Now, he was planning to fetch them from Baqubah and take them to Syria. "I haven't told my family I am coming back," said Azzawi, before getting into Khaisy's maroon Caprice Classic in Ruwayshid. "Maybe I am not going to see them." "Maybe I will get killed on the road." Seeking Safety, Aid Outside the restaurant, two sport-utility vehicles passed by, heading to Amman. One, with large red-checkered bags on its roof, carried Abu Saif al-Ajrami's family. The other vehicle carried their life's possessions. The Jordanians let them in after the family waited more than 24 hours at the border. It helped that Ajrami's father was Jordanian. At night, they arrived in Amman near a place refugees call Iraq Square, where taxis drop off recent arrivals. Two relatives, whom the family had not seen in five years, met them. There were hugs and kisses, and praises to God. "I feel psychologically relieved. You can see it is very safe," said Ajrami, waving his hands at the cars flowing by. "But I have left my family, friends, my neighbors, my memories back in Baghdad. The first day there is security, I will go back." Then he declared he would find a job the next day. "From the border to here, we felt like we had entered paradise," he said. Widad Shakur, 53, said that when she arrived in Amman in October, she felt the same way. A Shiite Muslim, she fled after Sunni extremists threatened to behead her daughter, a teacher. But Iraq's chaos is never far away. A week ago, Shakur learned that a Sunni family had occupied her house. Now, she cannot sleep at night. And she cannot afford to return to Iraq. Her daughter, a saleswoman, earns barely $300 a month, half of which goes to their rent. "I wish I was a bird and I could fly back to my house," said Shakur, as tears welled in her eyes. "Who expected it would turn out like this -- Sunni against Shia?" she continued. "We were like brothers. Why is this happening?" 3 She has a more pressing problem. Her legs hurt, she said. But she cannot afford a doctor. She worries that seeking help at a Jordanian hospital might lead to deportation, even though she has a three-month residency permit. "I don't know whether we have the right to go to it or not," said Shakur, who wore a black, sequined head scarf. "I am afraid to go there." At the Royal Association for Iraq Immigrants, Salah al-Samarai had 28 pink and yellow folders stacked on his desk. They belonged to Iraqis in need of surgeries. "I don't know what to do," said Samarai, the head of the nonprofit that helps Iraqis, as visitors waited outside his door. In front of him sat Waad Abdul Rahim, a solemn Iraqi professor dressed in a tweed jacket. His 14-year-old daughter, Mina, needed an intestinal operation. It cost $5,000. For the past month and a half, he has visited Samarai's office. "I come every day, and then I go back to suffer," Rahim said. "Her life is in danger. The longer it takes, the more dangerous it is going to be." Samarai nodded in sympathy and said, "We have four or five more-serious cases." Most of the organization's funds come from donations, he said. He doesn't blame the Jordanian government. "It's enough they opened their doors for us to stay here," Samarai said. But he wished the international community would do more to help. "Lots of Americans tell us we don't need money: 'You are wealthy.' I even went to the European Union. They also said, 'You don't need money.' " A Taste of Baghdad Rabab Haider and her husband, Ibrahim al-Shawy, live in an elegant, sunlit apartment in Amman. Along with other middle-class Iraqis, they live in a parallel Iraq. Many of their relatives and friends are here. Iraq's sectarian divisions rarely enter their lives. The richest Iraqis can get residency permits by depositing $70,000 in a Jordanian bank, buying property or investing. Others simply pay a $2 daily fine for expired permits. "I see more Iraqis here than I do in Baghdad," said Shawy, who travels every few months to Iraq, where he owns land. Qaduri, a popular restaurant nearby, was once an institution in Baghdad. Then it was bombed. Seven months ago, its owners decided to resurrect it in Amman. Now it serves tashreeb, a traditional Iraqi stew, from midnight to noon, just as it did in Baghdad. Next door, a sign reads that another restaurant plans to open soon. Its specialty: pacha, the dish of boiled lamb's head that Iraqis consider a delicacy. At a recent Iraqi wedding in the upscale Bristol Hotel, an Iraqi singer sang songs and guests moved to the drumbeats of the jobee, an Iraqi folk dance. In Baghdad, with the car bombs, checkpoints and kidnappings, large weddings are all but extinct. "You turned the clock back four years," Um Ammar, a guest who had recently arrived from Baghdad, told the groom's mother. The singer began to hum a patriotic Iraqi hymn. In the audience, eyes filled with tears. Others sobbed. Moments later, the singer crooned: "Baghdad." The audience responded: "In my eyes is Heaven." 4 "Baghdad," the singer sang again. "Is our one and only love," the audience sang. "Baghdad is our sole mother, may God safeguard you from the evil surrounding you." On a January afternoon, over cake and coffee in their Amman apartment, Haider and Shawy spoke of nostalgia, guilt and uncertainty. "What about the torment?" said Haider, a pleasant, short-haired woman with a faint British accent. "You being safe and your people in Baghdad are not." "How long can we keep this?" asked Haider, looking at their plush sofas, the purple vase, the glass dining table. Living in Fear On Jan. 18, a curly-haired artist named Qais Mohammed Ateih sat inside singer Saad Ali's tworoom apartment, which is nestled near a warren of shops and narrow alleys. A third Iraqi refugee, Razzaq al-Okaeli, 35, joined them. The trio spoke about being like beggars, depending on friends for meals. Ateih said he knew at least 70 Iraqis who have been deported since 2003. In the wake of Hussein's execution in December, many Iraqi Shiites say they have been targeted because of their sect. Jordan, a mostly Sunni nation, is home to many supporters of Hussein, who was a Sunni and a benefactor of Palestinians. "Is the government targeting us for being Shiites? No. But from individual policemen, we feel this," said Ateih, 36. "They say, 'You betrayed Saddam.' " If they are lucky, Ateih said, they find jobs as day laborers, earning $7 for a 14-hour workday. But Jordanian employers, they said, often exploit Iraqis. Okaeli said he recently worked for two months as an air-conditioning repairman; his employer paid him for only 10 days of work. "They know we cannot complain to the authorities," said Okaeli, a short man with brushed-back hair and long, trim sideburns. "If we complain, we will get deported." Ali sat on a worn brown sofa, rubbing his hands, taking in the conversation. He had hoped to earn enough money to help his parents in Baghdad. Now, when he speaks to them, he never reveals the truth. "They are inside Iraq. They should have to worry only about themselves," said Ali, his eyes lowered at the dusty red carpet. "So I tell them I am fine." He paused, then glanced at the tiny heater, and said, "I never expected it would be like this." Special correspondent Yasmin Mousa in Amman contributed to this report. 5 The Lebanese Crisis and Its Impact on Immigrants and Refugees By Kara Murphy Migration Policy Institute September 2006 Residents in Lebanon — citizens and foreigners — faced a perilous journey to evacuate the war-torn country and reach safe havens in Syria and Cyprus this summer. Before the ceasefire went into effect on August 14, up to 10,000 people arrived at the Syrian border each day, according to a report from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in early August. Other people arriving at the Syrian border included tourists from the Gulf region who were required to pay to enter Syria, as well as a number of poor Palestinian refugees who were rejected. About 15,000 American citizens (many of Lebanese origin) were evacuated, as were thousands of Europeans and Australians. Runways at Beirut's main airport, major bridges, and roads were destroyed by the Israeli military in the fight against Hezbollah that began July 12. In major southern cities like Tyre, infrastructure was so badly damaged that people often were trapped without access to food, water, electricity, or medical care. At press time, Lebanon’s total losses amount to an estimated $9.4 billion, according to Lebanon’s Higher Relief Commission. In cooperation with the Lebanese government and the United Nations, Sweden hosted an international donor conference on August 31 that brought together about 60 governments and organizations to discuss humanitarian needs and early reconstruction efforts in Lebanon. The plight of Lebanese citizens has received extensive media coverage around the world. However, another important population has been often left out of the picture: Lebanon's hundreds of thousands of migrant workers and refugees. Their hardships began well before the conflict, yet their stories were rarely told in the media. Estimates of the number of migrants in Lebanon vary widely since no official records are kept on the migrant population. In the formal economy, it is estimated that foreign workers, mainly from Sri Lanka and Egypt, make up 30 percent of the official workforce, particularly in the domestic and service sectors. Refugees, the majority of whom are Palestinian, and asylum seekers make up about 10 percent of the total Lebanese population of 3.9 million according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM). This article investigates the impact of the crisis on several vulnerable groups, including Lebanese citizens in Syria, internally displaced persons (IDPs), and Lebanon's migrant workers and refugees. Finally, it highlights the efforts of the Lebanese diaspora to help fellow nationals. Lebanese in Syria and the Internally Displaced By the time Lebanon and Israel signed the ceasefire agreement, the number of Lebanese displaced by the conflict had reached nearly one million. Of those, about 180,000 found refuge in Syria. Another 500,000 IDPs escaped to mountainous regions of Lebanon, where they were sheltered in schools or in homes of host families. 6 Throughout the crisis, the Syrian government has emphasized its support for Lebanon. Political support was also reflected in its general openness to displaced Lebanese arriving in Syria. In coordination with humanitarian organizations, including UNHCR and the Syrian Arab Red Crescent, the Syrian government has worked to provide shelter and relief to Lebanese. Even in poor rural towns, Syrians accepted refugees into their homes and donated what little food and blankets they owned. Given Syria's limited resources, UNHCR appealed to the international community in early August for help with relief efforts. UNHCR had received nearly $11 million (of nearly $19 million sought) as of August 17. In response, many countries, including Argentina, Bahrain, and others, sent assistance to Syria in the form of monetary contributions or shipments of supplies. The Turkish government sent nearly 40 truckloads of humanitarian supplies to assist Lebanese in need. Soon after the ceasefire announcement, many displaced Lebanese chose to make the journey home despite fears that they would have nothing to which to return. Because authorities and agencies are concentrating their relief operations in the hardest-hit towns, people in outlying areas remain in shelters, awaiting assistance to return home. Nearly 300,000 Lebanese in Syria and Lebanon are still displaced, Lebanon’s Higher Relief Commission reported on August 29. They either have no home return to or fear the return is too dangerous. Their fears are not unfounded: the Higher Relief Commission reported that in the two weeks after the ceasefire, nearly 60 people, including several children, were injured by still-active Israeli explosives in southern Lebanon. Both the displaced and returning populations suffer from a lack of food, medicine and safe drinking water. Since extreme fuel shortages shut down many hospitals, UNHCR and other aid agencies are coordinating relief operations to send 100 tons of fuel to southern Lebanon. Migrant Workers in Lebanon: A Brief Overview Workers from Sri Lanka, India, Vietnam, the Philippines, Ethiopia, and elsewhere have been coming to Lebanon since the oil boom of the 1970s. A majority of migrant workers are women, most of them working in the domestic sector. The governments of Sri Lanka and the Philippines encouraged emigration for the purpose of obtaining remittances from workers abroad. No formal agreements existed between Lebanese and Asian governments to facilitate the movement of migrants. Instead, Lebanese employment agencies established relationships with Asian agencies, and migrants were recruited based on the demands of Lebanese employers. This practice, facilitated by the Lebanese government’s laissez-faire labor-market policy, continues today. From the early 1900s until the start of the 15-year civil war in 1975, Lebanese households employed local and foreign Arab women as domestic workers. During the oil boom, Lebanese employers began importing Asian labor, a practice adopted from the Gulf states. This allowed them to hire workers who were more submissive and who would work for lower wages than Lebanese, Syrian, and other Arab workers. Additionally, as a result of heightened political tensions after the civil war, some employers preferred to hire Asian or African women, who were less likely to cause tension in the household than local Arab women who may have been from opposing religious or political factions. 7 Migrant Workers Currently, Lebanon's Central Administration of Statistics (CAS) maintains the only official record of migrants workers in the country: work permits. According to CAS, 90,000 work permits were issued to foreigners in 2002 (see Figure 1). But, according to some foreign embassy records, the number of their nationals is three times the CAS figure. While Sri Lanka's embassy estimated that around 160,000 of its nationals resided in Lebanon, only 32,497 reportedly held work permits; the rest, who number between 80,000 and 170,000, may hold expired work permits, be unemployed, or be in the country without authorization. The contract-labor work system in Lebanon isolates migrants from both the local population and from their home country. Employment agencies charge employers in Lebanon high fees to recruit the migrants. As a result, employers withhold their workers' passports to ensure they cannot leave. Indeed, since the fighting began, IOM has reported numerous cases of employers threatening migrants in order to prevent them from evacuating. Migrant workers without official identity or travel documents wanting to evacuate have had to go to their home government's embassy to get the needed documents or transportation to safety. However, some foreign governments, like that of Vietnam, do not have embassies in Lebanon. Migrants from those countries have been stranded for long periods without travel documents. Despite the dangers, many migrant workers have chosen not to leave, according to reports from aid workers. Their reasons vary from fear of losing their jobs to going home with no money after years of work to returning to a country where they have no home. Even governments with embassies in Lebanon Figure 1. Work Permit Holders in have lacked the capacity to help their nationals because Lebanon by Nationality, 2002 they are understaffed and underfunded. Those with some of the largest numbers of migrant workers —Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Ghana — also have the fewest resources to find and evacuate their nationals. Yet foreign governments have been willing to work together, even when their own resources were limited. For example, India agreed to allow Sri Lankan workers on their ships evacuating Lebanon, and Jordan and Syria offered 4,000 jobs to Sri Lankans escaping Lebanon. Still, neither Syria nor Jordan have clarified what long-term rights these migrants will be accorded. Most migrant workers in Lebanon have depended heavily on the help of international agencies, such as IOM, UNHCR, and CARITAS, a Catholic relief organization, which coordinate with embassies in order to assist stranded migrants. Since July 20, IOM has evacuated more than 13,000 migrants from Lebanon. Once in Syria, migrants were placed in shelters, where they waited until IOM could arrange their flights home. Following the ceasefire, IOM expected to evacuate at least 1,000 more third-country nationals provided adequate funding was available. Total Number of Work Permits Issued to Foreign Workers, 2002 = 88,73 Source: Central Administration for Statistics, Lebanese Republic According to a representative from IOM, security has been a major concern in its operations. Convoys carrying over 700 people at one time make a dangerous, three-hour passage 8 from Beirut to the border. Additionally, for migrants to return home, IOM had to coordinate with countries such as Saudi Arabia to allow charter flights over areas the organization had never flown over before. Thus far, foreign governments have supported IOM in its crisis-related efforts. Norway has provided IOM with tents, family kits, blankets, and other materials worth $640,000. The European Commission started a fund of 11 million euros to evacuate nationals from developing countries. This fund makes up more than half of the Commission's total relief budget for Lebanon. Individual European governments have also made significant contributions. Refugees in Lebanon Refugees and asylum seekers in Lebanon make up about 10 percent of the country's total population. Palestinians make up the majority of refugees, followed by Kurds, Iraqis, and Sudanese (see Table 1). Refugees have no official status in Lebanon, as the country has not signed the 1951 UN Convention relating to the Status of Refugees. UNHCR, which established an office in Beirut in the 1980s, keeps a close watch of refugees and asylum seekers. The United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), in existence since 1949, operates under a different mandate than UNHCR, and is responsible solely for Palestinian refugees. Although refugees came to Lebanon seeking safety from violence and instability in their home countries, the fighting has come to them. Lebanon's refugee camps became home to both refugees and Lebanese civilians in July. Many camps have been bombarded by Israeli attacks, including the country's largest Palestinian camp, where at least two refugees were killed and 15 were injured in August. Refugees who tried to flee Lebanon generally faced long wait times, or even rejection at the Syria-Lebanon border. Of the hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees, only 1,000 had been allowed into Syria by the end of July. Most of the stranded refugees held valid Lebanese-Palestinian documents but were nevertheless denied by Syrian officials. Table 1. Number of Refugees in Lebanon by Country of Nationality, 2004 UNHCR Iraq Sudan 1, 148 31 1 Soma 79 lia Other Total 21 5 1, 753 UNRWA UNRWA found that in the three main refugee camps in southern Lebanon, only around 2,900 out of 25,000 refugees left their camps. Attempts to supply water, Palest 39 electricity, and food to refugees still in camps proved inians 9,152 difficult as attacks intensified. Nevertheless, UNRWA reported that a total of nearly 29,000 displaced people Sources: 2004 UNHCR Statistical (both Palestinians and Lebanese) received aid. In addition, Yearbook. Available online; UNRWA in the agency opened numerous shelters in schools in both Figures, 2004 Syria and Lebanon to house Palestinian and Lebanese refugees. UNHCR reacted to complaints of rejection at the Syrian border by asking Syria to loosen border controls for Palestinian refugees. All governments, UNHCR stated, should follow the principle of nonrejection at their borders during this time of crisis. It asked states not to forcibly 9 return to Lebanon any migrants, including Lebanese citizens, any refugees or stateless persons, or any third-country national. Despite some setbacks, UNHCR expressed overall satisfaction with the Syrian government's cooperation in assisting all refugees coming from Lebanon. The Lebanese Diaspora During the 1975-1990 civil war, between 600,000 and 900,000 people fled the country. Since then, internal conflict and invasions from Israel have led to continued emigration. For this reason, Lebanese nationals living abroad number over one million, or about 25 percent of the actual number of people in Lebanon. However, some estimates put the number of people of Lebanese descent around the world as high as 15 million because of waves of emigration from Lebanon that date back to the late19th century. Current data show that the United States, Australia, Canada, and Brazil are among the most popular destination countries for Lebanese emigrants and their children. Past crises in Lebanon have provoked strong reactions from Lebanese communities worldwide, and the current conflict is no exception. From raising millions of dollars to setting up relief centers in Lebanon itself, Lebanese groups in the United States and Canada have provided much-needed aid to their home country. The Hairi Foundation, a nonprofit organization that promotes training for Lebanese scholars in the United States and Canada, gained media attention when it launched an emergency fund for Lebanon to help victims of the war. In Dearborn, Michigan, the Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services held fundraising events to raise $200,000 for medical supplies in Lebanon. A California-based organization, Islamic Relief, raised nearly $1 million by the first week of August for aid to Lebanon and Palestine. In addition to raising money, organizations are preparing homes and shelters to house fleeing Lebanese refugees. Community organizations have been building their capacity to receive thousands of soon-to-be homeless Lebanese-Canadians. Most of the Lebanese scheduled to arrive left Canada in the past 10 years to return to Lebanon but maintain dual LebaneseCanadian citizenship. Since July, protests against Israeli aggression have been a common occurrence in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Before a ceasefire agreement was reach in mid-August, Brazilian government officials had called for an end to the fighting. In an appeal to UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, Brazil's President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva emphasized that the Lebanese-Brazilian connection makes Brazil feel "directly affected by the violence against civilians in the region." Conclusion Many migrants and refugees in Lebanon have been trapped between a host country where they face danger and a home country to which they are hesitant or may not be able to return. For Lebanese, the return home is uncertain and dangerous, as the ceasefire agreement remains shaky. In the coming months, IOM plans to assist displaced Lebanese families as well as migrants, a number of which still want to return home. With its funds already running low, however, IOM will require an additional $26 million for future operations. The immediacy of the conflict in Lebanon makes it difficult to predict its lasting effects on vulnerable populations. Whatever the outcome, the impact of Lebanon's crisis on migrants and refugees will have implications for the entire Middle East. 10