Harnessing the Wind - The Evergreen State College

advertisement

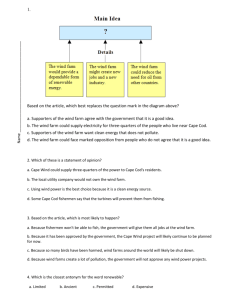

Cape Wind and the Sacred Sunrise of the Wampanoag: A Victory for Whom?1 By Kathleen M. Saul Abstract Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar has given the approval for the construction of the Cape Wind wind farm in Nantucket Sound, off the coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Supporters of the wind farm argue that this form of non-fossil fuel, nonpolluting energy will supply almost all of the peak energy demand for Cape Cod—about 420 MW. However, the local Wamponoag hold sacred the views of the sunrise over the area. Environmentally oriented opponents claim the wind turbines will negatively impact the local marine ecosystem. This case explores the use of turbines to harness the power of the wind and generate electricity, and outlines some of the key factors for wind farm location. The case then examines some of the environmental, cultural, and policy issues specific to the construction of Cape Wind. Despite tribal resistance to the development, can the outcome of the events surrounding this project be considered a victory for Native American rights? Salazar Approves Cape Wind Barbara sat at the kitchen table, scanning Indian Country Today for an article or two of interest. Finally, one headline caught her eye: “Salazar Approves Cape Wind” (Toensing, 2010). “Oh no!” she cried. “The U.S. government has given the go ahead to the wind farm off of Cape Cod! Listen to this! He finds ‘the public benefits weigh in favor of approving the Cape Wind project’ (Toensing, 2010). He thinks this will point us in ‘a new direction in our nation’s energy future’ and, while he “understood and respected the views of the tribes and the ACHP [Advisory Council on Historic Preservation] . . . [t]he need to preserve the environmental resources and rich cultural heritage of the Nantucket Sound must be weighed in the balance with the importance of developing renewable energy sources and strengthening our nation’s energy security while battling climate change and creating jobs’ (Toensing, 2010). I have heard that all before. What a bunch of baloney! And what a blow to Indian rights.” Linda looked up from her weaving project. “Not at all,” she said matter-of-factly. “The project is a victory for Native Americans. The government actually listened to the Wampanoag and forced the company reconsider the impact their plans would have on the 1 Copyright (2010) held by The Evergreen State College. Please use appropriate attribution when using and quoting this case. Cases are available at the Native Cases website at www.evergreen.edu/tribal/cases/home.htm. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0817624. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this case are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. Thank you to Dr. Linda Moon Stumpff for the inspiration and to Jovanna Brown, Barbara Smith, and Robert Cole for their input on earlier drafts of this case. 1 tribes.” Rob paused in his reading of the latest sports news and looked at his sisters, anxious to hear the lively debate that was about to unfold. How could it be that one wind energy project might be both a disappointment and a triumph for the tribes? Did one of the girls have her facts mixed up? And, who were the Wampanoag? He could have a lot of fun if that were the case. But first, he needed to know the basics. “Hey Linda, who are the Wampanoag? I’ve never heard of them.” “The Wampanoag have lived on Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket in Massachusetts for at least 10,000 years (“Wampanoag Tribe”; Sultzman). As the European settlers moved in, the natives were dislocated and many succumbed to disease, and by the 1800s there were only three Wampanoag communities left on Martha’s Vineyard. The Wampanoag of Aquinnah maintained control over their land and remained a sovereign tribe despite pressures to force them out. In the early 1970s, the Wampanoag began seeking federal recognition for the tribe, the return of tribal lands, and self-determination. That recognition was granted in 1987 through the Bureau of Indian Affairs. As part of the settlement, the Wampanoag were accorded trust lands in the southwest portion of Martha’s Vineyard in the town of Gay Head (now Aquinnah). Wampanoag, in English, means “People of the First Light” (Cope, 2006). These people were the first to see the rising sun each day for millennia, and that unobstructed view of the dawn remains an important part of their culture.” Robert squirmed in his seat. “Okay. But what is ‘wind farm’ anyway? How can you farm the wind?” he asked innocently. A Giant Whirligig Linda sighed and put down her work. “A wind farm isn’t a traditional farm at all. It’s an area of land, or in the case of Cape Wind, an area off the coast, on which a number of large wind turbines will be or have been erected to harness the power of the wind. “Wind results from differences in heating and cooling of the surfaces of the earth, the rising of warm air and the sinking of colder air masses (American Wind Energy Association [AWEA]). The sun heats up the earth’s atmosphere at different rates depending on the angle with which its rays hit the earth and how much the surface of the earth (land or water) reflects or absorbs the sun’s heat (AWEA). As a result, the temperature of the air varies with factors like elevation, proximity to the equator, and whether the air flows over the desert or the ocean. “The rising and sinking air--the wind--possesses kinetic energy, the energy of motion. When the wind comes into contact with the blades of a wind turbine, the kinetic 2 energy is transformed into rotational energy which causes the blades to turn. A generator inside the wind turbine then transforms the energy from that spinning motion into electricity (plus some heat, which gets lost to the atmosphere). “You aren’t really farming the wind, but you are capturing the energy of the wind to generate electricity.” “What does a wind turbine look like?” asked Rob. “It’s pretty simple actually,” chimed in Barbara. “Like a giant whirligig or pinwheel. It has a tall central shaft and three blades attached to the top to catch the wind.” She drew a quick sketch in the margin of the newspaper and held it up for Rob to see. “But why three blades? Why not six? Or sixteen?” asked Rob. “Lots of reasons,” Barbara responded. “First of all, the companies that make the wind turbines have found that turbines with three blades are the most stable (they don’t flop over in strong winds!). And, if the wind changes direction, the horizontal axis (the one parallel to the ground) also changes direction, rotating the top of the tower to keep it properly aligned with the wind, and maximizing power output. This movement is smooth for the three-bladed turbine but can be very jerky with only two blades, depending on the position of those blades. While the two-bladed version can be cheaper, it requires a higher wind speed to achieve the same energy output as the three-bladed design. And you would get less electricity from the two-bladed design in areas where wind speeds aren’t so high (Berg, 2009). “Increasing the number of blades adds a lot of strain to the turbine and increases its weight: Each blade weighs about seven tons! (Puget Sound Energy [PSE], “Hopkins Ridge”). The more blades on the turbine, the stronger the stronger the construction materials would need to be, and that would be more costly. After a lot of financial and engineering analyses, turbine manufacturers have deemed three blades are optimal. “Material strength and cost also play into the length of the blades and how tall the companies make the main shafts. The larger the area swept by the blades, the more energy the turbines can capture and transform into electricity. (See Appendix I.) Taller 3 towers can tap the energy of the higher, faster winds. Each company needs to find the ideal combination for them.” “If you want to catch the higher, faster winds, why not put all the wind turbines on the top of mountains?” Linda replied this time. “Good question. For one thing, it would be terribly hard to haul all the building materials to the top of a mountain, especially where there are no roads. You also need to be able to connect the wind farm to power lines so the electricity generated can be transmitted to the places where it is needed. There aren’t many power lines atop mountains. And, since there aren’t many cities or towns there either, companies would have to string up miles and miles of power lines to get the electricity to those areas. That would get very expensive and it would ruin the natural beauty of mountain areas. “Trees, hills, and cliffs in rural areas or even man-made structures can interrupt the flow of the wind, creating turbulence and making the wind speed erratic. Canyons and gullies can also affect the speed and direction of the wind. Since the wind and electric companies want a steady, predictable, reliable flow, they take all those factors into account when they locate their wind turbines. That is why you often see wind farms on flat, treeless expanses, where the wind blows all the time.” “The Rosebud Sioux Tribe in South Dakota took advantage of their wind (which blows at an average of 17 mph or more! (50 meters above sea level)) and installed a wind turbine that generates 750 kilowatts of electricity—enough to power about 200 – 300 homes for an entire year (“Owl Feather War Bonnet;” “Rosebud Wind,” 2003; “PSE, “Wild Horse Wind and Solar’). When dedicated on May 1, 2003, that wind turbine became the first utility scale commercial wind development in the continental U.S. on tribal land, and wholly owned and operated by a tribe (“Rosebud Sioux,” 2003). The project has led to plans for other wind turbines on the reservation as a means of generating revenue for the tribe (“Owl Feather War Bonnet”). Barbara piped in, “There also are projects in development for the Pine Ridge reservation and at the Flandreau Santee Sioux casino, for tribes in Montana, and even in Alaska!” (“Native Wind;” National Renewable Energy Laboratory [NREL], “Wind Power,” 2005). Rob looked puzzled. “I thought you said Cape Wind was off the coast. Aren’t those all land-based projects?” Horseshoe Shoal “You’re right,” said Linda. “Any rough, irregular surface can slow down the wind and add to its turbulence. Wind glides over the smooth surface of water and creates more electricity than would the same wind over land. That makes an offshore wind farm preferable to one on land. At the Cape Wind site in Nantucket Sound, the wind can blow 4 at about 20 mph (at 20 meters above sea level) (Current Conditions, 2010). Ideally, you would want wind speeds of about 31 mph (PSE, “Wild Horse, Facts”). “Two other factors are critical in siting an offshore wind farm. You need the water to be relatively shallow and you don’t want really high waves during storms) (“Why is Cape Wind Proposing”). You need to be able to erect the turbines, service them, keep them standing throughout the year, and be able to connect them to the local power grid. According to the Environmental Impact Statement for the Cape Wind project, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers evaluated 17 different sites and found the Horseshoe Shoal area to be the best of those sites. It had the appropriately high wind speeds, proximity to lines with surplus transmission capacity, and an area that would accommodate a 200 – 1500 MW wind project (Draft Environmental Impact Study [EIS], 2007, p.1-2). “Here’s a map that shows you where in Massachusetts the Nantucket Sound is located. 5 Cape Wind wind park site Figure 1: Road Map of Eastern Massachusetts, Cape Cod From: http://www.aaccessmaps.com/show/map/us/ma/mass_capecod_e 6 “And here’s a closer view of the specific location of the wind farm and the existing power transmission lines. You can see that the current shipping and ferry routes skirt the chosen site.” Cape Cod Martha’s Vineyard Nantucket Island Figure 2: Location of the Proposed Cape Wind Wind Park From: http://news.cnet.com/i/bto/20100105/map.JPG Rob studied the maps for a minute, then looked up. “You mentioned an Environmental Impact Statement. What’s that?” Rob asked. “The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) was signed into law way back in 1970, after concerns about pesticide use, water pollution, smog, and other issues had gained a foothold in American consciousness (Environmental Protection Agency [EPA], “National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)”, 2010). NEPA requires that all levels of the government “create and maintain conditions under which man and nature can exist in productive harmony” (“National Environmental Policy Act of 1969”). Those responsible for any project that may impact the natural environment or which is environmentally controversial must prepare an environmental analysis and complete an Environmental Impact Statement. In general, the Environmental Impact Statement (or EIS) outlines the scope of, purpose of, and need for a specific project (EPA, “Frequently Asked Questions”). It examines the natural environment that might be affected by the project 7 and the consequences the project could have on that environment. It also needs to outline alternatives to the proposed project. “The Army Corps of Engineers prepared the EIS on behalf of Cape Wind. It stated that the purpose of the project was to address the need for additional power in the region, particularly from renewable energy sources, and reduce the dependency on nonlocal sources (“Draft EIS,” 2007, p. 1-2). Originally they did not rule out on-shore locations, and actually compared one on-shore site, the Horseshoe Shoal site, a deeper water location, and a combination of smaller installation at Horseshoe Shoal and another offshore site (“Draft EIS,” 2007, p. 1-3). In the end, they proposed using the Horseshoe Shoal site, with 130 wind turbines positioned in a grid, a minimum of about 4/10 of a mile apart (“Draft EIS,” 2007, p. 1-3). That spacing was chosen to “not preclude or prohibit traditional uses” of the area, including fishing, boating, or other commercial or recreational activities.” Rob thought a bit, and looked back at the maps. “That many wind turbines probably would have some impact on the environment there.” “I would think so, but the Army Corps thinks otherwise,” inserted Barbara. “In the EIS they say that the disturbance of the sea floor will generate some impact, but it will be only temporary. Since most of the creatures in the area a mobile (like fish, turtles, seals), they expect them to move away from the site during the construction phase, but return after the disruptions are over. Some of the work may impact eggs and larvae, however. On land, bats and birds have been greatly impacted by wind projects, especially the early ones that failed to account for bird migratory patterns (Cryan, 2008; DeLucas et al., 2005; Everaert and Stienen, 2006; Smallwood and Thelander, 2008). The Army Corps insists that the majority of birds in the Cape Wind area fly much lower than the rotors (which will not come within about 75 feet of the surface of the water) (“Draft EIS,” 2007, p. 1-13). They also claim that the wide spacing of the turbines, the tubular construction, and the slow speed of the blades will help prevent bird and bat deaths. “In addition, the turbines also will be equipped with fog horns to prevent ships and boats from colliding with them in heavy fog. However, those fog horns have a ½ mile audible range so that people on land won’t be able to hear them. “The EIS does indicate that any construction noise will be well below the levels that would cause permanent damage to fish. During operations, the wind farm will produce very little noise. “Still, this is the first off-shore wind farm in the U.S. and there are a lot of unknowns (Conservation Law Foundation, “Environmental Organizations Applaud,” 2010). The Army Corps of Engineers based their conclusions on simulation models, the input of the Minerals Management Service, the Department of Fish and Wildlife and others, and on offshore wind farm experience in Europe, but until a turbine is erected in 8 these particular waters, those conclusions are suppositional (Venkataraman and Ebbert, 2009). Just listen to the language used in the EIS: “. . .finfish. . .are likely to be able to find suitable benthic habitat adjacent to the Project area. . .” (“Draft EIS,” 2007, p. 1-9), “. . . sea turtles should be able to easily avoid vessels. . .” (“Draft EIS,” 2007, p. 1-10), and increases in the sediments in the water “. . .could have minor indirect effects on birds by temporarily affecting their prey and food availability (emphasis added)” (“Draft EIS,” 2007, p. 1-12). Linda countered her sister. “Even though some environmental groups and local fishermen (through the Massachusetts Marine Fisheries Commission) have voiced concern about the project, others (like Clean Power Now and the Natural Resources Defense Council) applaud the move to a renewable, non-carbon fuel source in the Northeast (“A Big Win,” 2010; Doggett, 2009; “Wind Farm Debate,” 2002). This project will provide almost all of the peak energy demand for Cape Cod—about 420 MW (Wind Farm Debate, 2002). According to the American Lung Association, Cape Cod has some of the worst air quality in the state of Massachusetts, so the reduction in the use of fossil fuels to produce that electricity, and the associated pollution, would be a step in the right direction” (“Barnstable County,” 2003). “So where do the tribes fit into all of this?” wondered Rob. “Not in Our Backyard” “From the beginning, there has been opposition to a wind farm off the shores of Cape Cod, Nantucket, and Martha’s Vineyard,” said Barbara, in a matter-of-fact tone. “Many residents, including the late Ted Kennedy, disliked the thought of 440 foot tall wind turbines obscuring their views (Linday, 2009). Those areas also house 34 properties listed on the National Register of Historic Places, 16 historic districts, and 12 significant historic properties (“Cape Wind Rejection Recommended,” 2010). According to Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act, any federal department or independent agency which has the authority to license a project such as this one, must “take into account the effect of the undertaking on any district, site, building, structure, or object that is included in or is eligible for inclusion in the National Register” (Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, “National Historic Preservation Act”). The local Mashpee and Aquinnah Wampanoag tribes claim the Nantucket Sound is eligible for such a listing as a traditional cultural property (Daley, 2009). “The religious and ceremonial rites of the tribes, also known as “People of the First Light,” require an unobstructed view of the rising sun. According to Bettina Washington, tribal historic preservation officer, “The Nantucket Sound viewscape is essential to our spiritual well-being” (Lehmann, 2009). In addition, tribal oral history indicates the Horseshoe Shoal is a place where their ancestors hunted, lived, and were buried (Cassidy, 2009). Western scientists have shown that during the last ice age, the New England coast extended 75 miles farther out than it does today (Daley, 2009). Still, Cape Wind officials counter that no evidence of any human activity (remains or artifacts) 9 has been found in any of the sediment samples taken from the proposed site. It’s a conflict of oral history against western science.” “There is more to it than that,” Linda insisted. “Although some people claim that the tribal concerns arose very late in the project, almost as a last minute attempt to stall the installations, the Wampanoag have been trying to assert their claims for quite some time. As early as 2004, the tribes were in communication with federal officials, telling them that the Nantucket Sound was critical to their spiritual well-being (Daley, 2009; Lehmann, 2009). Unfortunately, they weren’t taken very seriously by the agency in charge, the U.S. Minerals Management Service (the MMS) (Cassidy, 2009). In early 2009, the MMS did issue a report that outlined adverse impacts of the wind farm on 28 historic properties and the “traditional religious and ceremonial practices” of the Wampanoag (Daley, 2009). But nothing came of it and in the middle of the summer, the Aquinnah Wampanoag wrote the MMS a letter expressing concern about their lack of engagement with the tribes. Other tribal members complained that keeping on schedule and reaping the profits of the wind farm took precedence over Native American cultural issues” (Lehmann, 2009). “Why is the Minerals Management Service involved in wind farming?” asked Rob. Linda replied, “Minerals Management Service is actually an outdated title for the agency. As of June 2010, they became known as the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement (Minerals Management Service [MMS], “Salazar Swears In,” 2010). It is the agency responsible for offshore energy sources, including oil, natural gas, and now, wind. And it reports up through the Department of the Interior, charged with protecting the country’s natural resources and heritage, supplying energy for the future, and, supposedly, honoring cultures and tribal communities (U.S. Department of the Interior, “Our Mission”). “Returning to the Cape Wind case . . . “The real breakthrough occurred in February when the Secretary of the Interior, Ken Salazar, journeyed north and participated in a sunrise meeting with the tribes on Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard (Daley, 2010). Salazar was quoted as saying the meetings were “very meaningful” (Daley, 2010). And tribal representative indicated that for the first time, the concerns of the Wampanoag were actually being heard.” Barbara spoke up. “The concerns may have been heard, but they didn’t seem to affect the final decision. Even though the National Park Service did determine that the site did qualify for status as a traditional cultural property, and even though the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation recommended that Salazar not approve the project, he did so any way” (“Cape Wind Rejection Recommended,” 2010). “Perhaps. But Cape Wind has been required to reduce the number of wind turbines from 170 to 130, to change the design and configuration of the wind farm to 10 lessen the impacts of the project on the viewscape, and to conduct additional surveys of the seabed in the area to ensure they locate any archeological remains before the construction actually begins (Sigelman, April 2010). If they find any cultural resources, operations will cease and the Tribes will participate in reviewing and analyzing the finds (Barkoff and Bullin, 2010).” Barbara shrugged. Linda continued, a bit perturbed. “Think of what has happened at other Indian sacred sites. Think of the San Francisco Peaks. Those peaks are sacred to the Apache, Navajo, Hope, Hualapai, and Havasupai tribes, and others. To them those peaks are as a living being (Fischer, 2009). Yet the owners of the Arizona Snowbowl ski resort want to expand their offerings by using treated wastewater to make artificial snow (“Tribes Hopeful,” 2006). The U.S. Forest Service claimed to have conducted outreach among the tribes, but didn’t bother to translate the documents into the Tribal languages (for those who don’t speak English), to explain their content, to provide any forums or meetings to ensure public understanding of the project and participation in the process (George, 2004, p. 22). Nor were there any notices on Indian radio or in Indian newspapers (George, 2004, p. 24). And, the former Secretary of the Interior (Bruce Babbitt) even joined the Arizona Snowbowl legal defense team (Cole, 2005)! With Cape Wind, the Tribes have been actively involved and the current Secretary of the Interior has listened to and taken into account their concerns. Although we may not like his decision in favor of the project, his engagement with the Tribes sets an important precedent.” Linda turned to her brother. “So Rob, what do you think? Is the Cape Wind case a victory for Native Americans, or another example of Native rights and traditions being ignored, or something in between?” 11 Appendix I: The Area Swept by the Rotor Blades (m) and Turbine Energy Output (kW) From: www.windpower.org 12 Appendix II: Wind Resource Potential in the United States From: http://www.eia.doe.gov/cneaf/solar.renewables/ilands/fig13.html 13 Appendix III: The Law of Wind Adapted from: The Law of Wind: A Guide to Business and Legal Issues, 5th Edition. (2009). Stoel Rives Attorneys at Law, Portland, OR. Chapter 5: Tribal Laws and Land Issues. “Federal and tribal laws govern leases, easements, and other agreements for use of tribal land within Indian reservations. In addition, as governments, Indian tribes exercise significant regulatory control over use of tribal land and Indian reservation land generally. Federal laws of general application, such as federal environmental, energy, and tax laws, and some state laws also apply to wind energy project developers on tribal land. In general, even with tribal consent, tribal land can be sold, leased, encumbered by an easement, or used as security for financing only as authorized by federal Indian law and applicable tribal law . . . [A]n Indian tribe, as lessor, can lease tribal land for 25 years and may agree to an option extending the lease for an additional 25 years.” However, under the Energy Policy Act of 2005, the Secretary of the Interior issued regulations for Tribal Energy Resource Agreements (TERAs). “Once an Indian tribe and the BIA enter a TERA covering wind energy development, the tribe can enter into wind energy leases and other business agreements and issue rights-of way easements for projects on tribal lands for 30 years, renewable for another 30 years by the tribe, all without BIA approval. To protect project wind flow from being disturbed by other development on tribal lands, “it may be appropriate to combine a section lease of tribal land with an “encumbrance” on other tribal land.” Such an encumbrance may include right-of-way agreements or easements which prevent development of that specific land to permit the establishment of project-related transmission lines, roads, or other project activities. Key federal environmental laws that apply to projects on tribal land include the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), and the Endangered Species Act (ESA). “Under NEPA, the BIA must prepare an environmental impact statement before approving the lease of tribal land or taking other action . . . The BIA must take into account the impact of its actions on any property, including traditional cultural properties, listed on or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places and must consult with tribes and other interested parties on measure to avoid, minimize, and mitigate any adverse impacts of its action on such properties.” The BIA must consult with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or the National Marine Fisheries Service “if its action may affect species or designated critical habitat of species listed as threatened or endangered under the ESA. Other federal laws apply if human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, or archaeological resources are encountered before or during project development on tribal land.” “A tribe does not waive its governmental regulatory authority by entering into contracts for development of tribal land and resources.” Developers need to be aware of and understand the impact of tribal laws and regulations on a wind energy project. In addition, “[n]ontribal project developers may be subject to applicable state and tribal taxes. Careful review should be conducted to determine whether a Wind Energy Land 14 Agreement . . . can be designed to avoid or minimize the risk of double taxation. In some cases, Indian tribes are willing to abate tribal taxes to the extent necessary to avoid or minimize the economic impact. . .” Federal law also allows for accelerated depreciation of certain investments on tribal land. “As governments, Indian tribes have sovereign immunity. This means an Indian tribe cannot be sued in any court without the express consent of Congress or the tribe itself by appropriate tribal government action. Most tribes are willing to waive tribal sovereign immunity on a limited basis to promote significant tribal economic development projects. A dispute resolution clause in an agreement with an Indian tribe typically includes a clause designating the court or courts authorized to exercise jurisdiction over a dispute with the tribe . . . Developers are often reluctant to agree to have such disputes heard in a tribes’ tribal court. To address this dilemma, many Indian tribes will agree to a dispute resolution clause designating binding arbitration as the exclusive means of resolving disputes.” 15 Appendix IV: Cape Wind Project Regulatory Requirements Adapted from: Draft Environmental Impact Study. (2007, February). Section 1.0, Executive Summary, pp. 1-24 to 1-26. Retrieved June 29, 2010 from http://www.capewind.org/FAQCategory10-Permitting+Process+and+Cape+Wind-Parent0-myfaq-yes.htm Agency Responsible Permit/Action Date Applied U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Permit for work in navigable waters 11/22/01 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Review for compliance with National Historic Preservation Act To be filed Council on Environmental Quality, NEPA Draft Environmental Impact Statement 11/2004 Council on Environmental Quality, NEPA Final Environmental Impact Statement To be filed Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Stormwater Permit To be filed Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Notice of Proposed Construction for structures exceeding 200 ft in navigable airspace 10/25/02 U.S. Coast Guard Permit to establish and To be filed operate private aid-to-navigation on a fixed structure Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act (MEPA) Environmental Notification 11/15/01 MEPA Draft Environmental Impact Report 11/15/04 MEPA Final Environmental Impact Report To be filed Massachusetts Energy Facility Siting Board Petition to Construct Jurisdictional Facility 9/17/02 Date Approved 4/9/03 4/22/02 7/2/04 (tentative) 16 Agency Responsible Permit/Action Date Applied Massachusetts Energy Facility Siting Board Certificate of Impact and Public Need Pending Massachusetts Dept. of Waterways License Environmental Protection— Wetlands and Waterways Regulation Program To be filed Massachusetts Dept. of Water Quality Environmental Protection— Certification Wetlands and Waterways Regulation Program To be filed Massachusetts Coastal Zone Management 11/21/01 Concurrence with Federal Consistency Certification Statement Date Approved Massachusetts Ocean Regulatory Review Sanctuaries Act, Dept. of Environmental Management Ongoing Massachusetts Highway Dept. Permit to Access State Highway To be filed State Historic Preservation Office Regulatory Review To be filed Massachusetts Historical Commission: State Archeaologist Permit for Upland Reconnaissance Archaeological Survey 3/12/03 3/28/03 Massachusetts Historical Commission: State Archeaologist Permit for Upland Intensive Archaeological Survey 9/18/03 9/23/03 Massachusetts Board of Underwater Archaeology Reconnaissance and Excavation Permits To be filed if required Cape Cod Commission Development of Regional Impact Review 11/15/01 Pending 17 Agency Responsible Permit/Action Date Applied Yarmouth Conservation Commission Notice of Intent/ Issuance of Order of Conditions To be filed Barnstable Conservation Commission Notice of Intent/ Issuance of Order of Conditions To be filed Yarmouth Dept. of Public Works (DPW) Street Opening Permit To be filed Barnstable (DPW) Street Opening Permit To be filed Date Approved 18 References: Advisory Council on Historic Preservation. (Undated). National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, As Amended through 2006, p. 19. Retrieved June 30, 2010 from http://www.achp.gov/docs/nhpa%202008-final.pdf American Wind Energy Association. (Undated). Wind Energy Basics. Retrieved June 26, 2010 from http://www.awea.org/faq/wwt_basics.html The Area Swept by the Rotor Blades (m) and Turbine Energy Output (kW) [Map]. (1998). Retrieved October 22, 2009 from www.windpower.org Barkoff, K. and L. Bullin. (2010, April 28). Secretary Salazar Announces Approval of Cape Wind Energy Project on Outer Continental Shelf of Massachusetts. Retrieved October 18, 2010 from http://www.doi.gov/news/doinews/SecretarySalazar-Announces-Approval-of-Cape-Wind-Energy-Project-on-Outer-ContinentalShelf-off-Massachusetts.cfm Barnstable County has Worst Air Quality in Massachusetts. (2003, May 01). Retrieved June 30, 2010 from http://www.capewind.org/news76.htm Berg, D. E. (2009, January 26). Why Do Wind Turbines Have Three Narrow Blades, but Ceiling Fans have Five Wide Blades? Scientific American. Retrieved October 21, 2009 from http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=wind-tubine-fanblades A Big Win or Massachusetts Jobs, Cape Wind Success Seen as Triumph of People Speaking Out through Grassroots Organization. (2010, April 28). Retrieved June 24, 2010 from http://cleanpowernow.org/pr_salazar_cape_wind.html Cape Wind Rejection Recommended. (2010, April 9). Indian Country Today. Retrieved June 26, 2010 from http://www.indiancountrytoday.com/internal?st=print&id=90350259&path=/archive Cassidy, P. (2009, November 16). Historic Designation Could Change Sound. Retrieved June 24, 2010 from http://www.capecodonline.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20091116/NEWS/911160 310 Cole, C. (2005, July 1). Bruce Babbitt Added to Snowbowl Legal Team. Arizona Daily Sun. Retrieved October 28, 2010 from http://www.savethepeaks.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=72& Itemid=13 Conservation Law Foundation. (2010, April 28). Environmental Organizations Applaud Obama Decision to Approve Cape Wind, First Offshore Wind Facility in 19 United States. Retrieved June 24, 2010 from http://www.clf.org/press/pressreleases/pressreleasearchive/2010/2010-4-28.html Cope, Amy. (2006). People of the First Light. WordClay, www.wordclay.com Cryan, P. M. (2008, April). Mating Behavior as a Possible Cause of Bat Fatalities at Wind Turbines. Journal of Wildlife Management, Vol. 72, No. 3, pp. 845 – 849. Current Conditions for June 28, 2010. Derived from http://capewind.whgrp.com Daley, B. (2009, October 26). Two Tribes Object to Cape Wind Turbines. The Boston Globe. Retrieved June 24, 2010 from www.boston.com/lifestyle/green/articles/2009/10/26/2_tribes_object_to_cape_wind_t urbines/ Daley, B. (2010, February 3). Tribes Get a Hearing on Wind Farm Opposition. The Boston Globe. Retrieved June 24, 2010 from http://www.boston.com/news/local/massachusetts/articles/2010/02/03/tribes_get_a_h earing_on_wind_farm_opposition/ DeLucas, M. et al. (2005). A Bird and Small Mammal BACI and IG Design Studies in a Wind Farm in Malpica (Spain). Biodiversity and Conservation, Vol. 14, No. 13, pp. 3289 – 3303. Doggett, T. (2009, January 16). Cape Wind Project Gets Favorable U.S. Government Review. Retrieved June 24, 2010 from http://www.reuters.com/article/idUKN1629514220090116 Draft Environmental Impact Study. (2007, February). Section 1.0, Executive Summary, p. 1-2. Retrieved June 29, 2010 from http://www.capewind.org/FAQCategory10-Permitting+Process+and+Cape+Wind-Parent0-myfaq-yes.htm Environmental Protection Agency. (Undated). Frequently Asked Questions: National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). Retrieved June 29, 2010 from http://www.epa.gov/compliance/resources/faqs/nepa/index.html#a5 Environmental Protection Agency. (2010, March 18). National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA): Basic Information, Retrieved August 26, 2010, from http://www.epa.gov/oecaerth/basics/nepa.html Everaert, J., and E. Stienen. (2006, November). Impact of Wind Turbines on Birds in Zeebrugge (Belgium): Significant Effect on Breeding Tern Colony Due to Collisions. Biodiversity and Conservation, Vol. 16, No. 12, pp. 3345 – 3359. Fischer, H. (2009, June 9). Snowmaking Wins Legal OK. Retrieved October 18, 2010 from 20 http://www.savethepeaks.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=104 &Itemid=13 George, R. et al. (2004, April 12). Comments on the Draft Environmental Impact Statement for Arizona Snowbowl Facilities Improvements. Retrieved October 18, 2010 from http://www.savethepeaks.org/images/stories/documents/deis_comments.pdf The Law of Wind: A Guide to Business and Legal Issues, 5th Edition. (2009). Stoel Rives Attorneys at Law, Portland, OR. Chapter 5: Tribal Laws and Land Issues. Lehmann, E. (2009, October 5). Pioneering Wind Farm Faces Another Delay, This Time Over Indian Sites. The New York Times. Retrieved June 24, 2010 from http://www.nytimes.com/cwire/2009/10/05/05climatewire-pioneering-wind-farmfaces-another-delay-thi-73053.html Lindsay, Jay. (2009, November 6). Tribes Seek Halt to Proposed Cape Cod Wind Farm. Indian Country Today. Retrieved June 26, 2010 from http://www.indiancountrytoday.com/internal?st=print&id=6937922&path=/archive Location of Proposed Cape Wind Wind Park [Map]. (2010). Retrieved September 11, 2010 from http://news.cnet.com/i/bto/20100105/map.JPG Minerals Management Service. (2010, June 21). Salazar Swears In Michael R. Bromwich to Lead Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement. Retrieved July 1, 2010 from http://www.mms.gov/ooc/press/2010/press0621 National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, Portions, As Amended. (Undated). Retrieved August 26, 2010 from http://www.nps.gov/history/locallaw/fhpl_ntlenvirnpolcy.pdf National Renewable Energy Laboratory. (2005, April 30). Wind Power on Native American Lands: Process and Progress. Retrieved June 29, 2010 from http://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy05osti/38125.pdf Native Wind Projects. (Undated). Retrieved June 29, 2010 from http://www.nativewind.org/html/projects.html Owl Feather War Bonnet Wind Farm. Rosebud Sioux Tribe. (Undated). Retrieved June 26, 2010 from http://apps1.eere.energy.gov/tribalenergy/pdfs/0510review_05haukaas.pdf Puget Sound Energy. (2009, June). Hopkins Ridge, Facts at a Glance. Retrieved June 28, 2010 from http://www.pse.com/energyEnvironment/energysupply/pages/EnergySupply_Electrici tyWind.aspx?tab=2&chapter=5 21 Puget Sound Energy. (Undated). Wild Horse, Facts at a Glance. Retrieved June 28, 2010 from http://www.pse.com/energyEnvironment/energysupply/pages/EnergySupply_Electrici tyWind.aspx?tab=3&chapter=5 Puget Sound Energy. (Undated). Wild Horse Wind and Solar Facility. Retrieved June 28, 2010 from http://www.pse.com/energyEnvironment/energysupply/pages/EnergySupply_Electrici tyWind.aspx?tab=3&chapter=1 Road Map of Eastern Massachusetts, Cape Cod. (2000). Retrieved September 11, 2010 from http://www.aaccessmaps.com/show/map/us/ma/mass_capecod_e Rosebud Sioux Wind Turbine Dedicated. (2003, June). Native Energy. Retrieved June 26 2010 from http://www.nativeenergy.com Rosebud Wind Turbine, a Showcase for the Northern Plains. (2003, April 1). Indian Country Today. Retrieved June 26, 2010 from http://www.indiancountrytoday.com/archive/28182434.html Sigelman, N. (2010, February 25). Wampanoag Cultural Claims False, Some Say. The Martha’s Vineyard Times. Retrieved June 24, 2010 from http://www.mvtimes.com Sigelman, N. (2010, April 29). Secretary Salazar Approves Cape Wind Project in Sound. The Martha’s Vineyard Times. Retrieved October 18, 2010 from www.mvtimes.com/marthas-vineyard/article.php?id=555 Smallwood, K. S., and C. Thelander. (2008, January). Bird Mortality in the Altamont Pass Wind Resource Area, California. Journal of Wildlife Management, Vol. 72, No. 1, pp. 215 – 223. Sultzman, L. (Undated). Wampanoag History. Retrieved October 11, 2010 from http://www.tolatsga.org/wampa.html Toensing, G. C. (2010, March 29). Salazar Approves Cape Wind. Indian Country Today. Retrieved June 26, 2010 from http://www.indiancountrytoday.com/archive/92318759.html Tribes Hopeful After Court Hears Sacred Site Case. (2006, September 19). Indianz.com. Retrieved October 18, 2010 from http://www.savethepeaks.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=86& Itemid=13 22 U.S. Department of the Interior. (Undated). Our Mission: Protecting America’s Great Outdoors and Powering Our Future. Retrieved July 1, 2010 from http://www.doi.gov/ Venkataraman, B., and S. Ebbert. (2009, January 16). Cape Wind Receives Favorable Federal Environmental Review. Retrieved June 24, 2010 from http://www.boston.com/lifestyle/green/greenblog/2009/01/cape_wind_receives_favor able_f.html Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head: History and Culture. (Undated). Retrieved June 24, 2010 from http://www.wampanoagtribe.net/Pages/Wampanoag_WebDocs/history_culture Where Does Wind Energy Come From? (Undated). Retrieved June 28, 2010 from http://www.windpower.org/en/tour/wres/index.htm Why is Cape Wind Proposing its Wind Farm to be located on Horseshoe Shoal in Nantucket? Retrieved June 24, 2010 from http://www.capewind.org/FAQCategory6-Offshore+Wind-Parent0-myfaq-yes.htm#34 Wind Energy Basics. (Undated). Retrieved June 28, 2010 from http://windeis.anl.gov/guide/basics/index.cfm Wind Farm Debate: A Close Look at the Claims. (2002, September 29). Retrieved June 24, 2010 from http://www.archive.capecodonline.com/special/windfarm/windfarm0929.htm Wind Resource Potential [Map]. (2003). Retrieved October 22, 2009 from http://www.eia.doe.gov/cneaf/solar.renewables/ilands/fig13.html 23